Our Missouri Podcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE TELEVISED SOUTH: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DOMINANT READINGS OF SELECT PRIME-TIME PROGRAMS FROM THE REGION By COLIN PATRICK KEARNEY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Colin P. Kearney To my family ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A Doctor of Philosophy signals another rite of passage in a career of educational learning. With that thought in mind, I must first thank the individuals who made this rite possible. Over the past 23 years, I have been most fortunate to be a student of the following teachers: Lori Hocker, Linda Franke, Dandridge Penick, Vickie Hickman, Amy Henson, Karen Hull, Sonya Cauley, Eileen Head, Anice Machado, Teresa Torrence, Rosemary Powell, Becky Hill, Nellie Reynolds, Mike Gibson, Jane Mortenson, Nancy Badertscher, Susan Harvey, Julie Lipscomb, Linda Wood, Kim Pollock, Elizabeth Hellmuth, Vicki Black, Jeff Melton, Daniel DeVier, Rusty Ford, Bryan Tolley, Jennifer Hall, Casey Wineman, Elaine Shanks, Paulette Morant, Cat Tobin, Brian Freeland, Cindy Jones, Lee McLaughlin, Phyllis Parker, Sue Seaman, Amanda Evans, David Smith, Greer Stene, Davina Copsy, Brian Baker, Laura Shull, Elizabeth Ramsey, Joann Blouin, Linda Fort, Judah Brownstein, Beth Lollis, Dennis Moore, Nathan Unroe, Bob Csongei, Troy Bogino, Christine Haynes, Rebecca Scales, Robert Sims, Ian Ward, Emily Watson-Adams, Marek Sojka, Paula Nadler, Marlene Cohen, Sheryl Friedley, James Gardner, Peter Becker, Rebecca Ericsson, -

Spring 2021 Mayberry Magazine

Spring 2021 MayberryMAGAZINE Mayberry Man Andy Griffith Show Movie nearing release A star comes to visit Andy Finds Himself Mayberry Trivia College opened new Test your knowledge world What’s Happening? Comprehensive calendar ISSUE 30 Table of Contents Cover Story — Finally here? Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, work on the much ballyhooed Mayberry Man movie has continued, working around delays, postponements, and schedule changes. Now, the movie is just a few months away from release to its supporters, and hopefully, a public debut not too long afterward. Page 8 Andy finds himself He certainly wasn’t the first student to attend the University of North Carolina, nor the last, but Andy Griffith found an outlet for his creative talents at the venerable state institution, finding himself, and his career path, at the school. Page 4 Guest stars galore Being a guest star on “The Andy Griffith Show” could be a launching pad for young actors, and even already established stars sometimes wanted the chance to work with the cast and crew there. But it was Jean Hagen, driving a fast car and doing some smooth talking, who was the first established star to grace the set. Page 6 What To Do, What To Do… The pandemic put a halt to many shows and events over the course of 2020, but there might very well be a few concerts, shows, and events stirring in Mount Airy — the real-life Mayberry — this spring and summer. Page 10 SPRING 2021 SPRING So, You Think You Know • The Andy Griffith Show? Well, let’s see just how deep your knowledge runs. -

THE WIZARD of OZ an ILLUSTRATED COMPANION to the TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC by John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan with a Foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini

THE WIZARD OF OZ AN ILLUSTRATED COMPANION TO THE TIMELESS MOVIE CLASSIC By John Fricke and Jonathan Shirshekan With a foreword by M-G-M “Munchkin” Margaret Pellegrini The Wizard of Oz: An Illustrated Companion to the Timeless Movie Classic is a vibrant celebration of the 70th anniversary of the film’s August 1939 premiere. Its U.S. publication coincides with the release of Warner Home Video’s special collector’s edition DVD of The Wizard of Oz. POP-CULTURE/ ENTERTAINMENT over the rainbow FALL 2009 How Oz Came to the Screen t least six times between April and September 1938, M-G-M Winkie Guards); the capture and chase by The Winkies; and scenes with HARDCOVER set a start date for The Wizard of Oz, and each came and went The Witch, Nikko, and another monkey. Stills of these sequences show stag- as preproduction problems grew. By October, director Norman ing and visual concepts that would not appear in the finished film: A Taurog had left the project; when filming finally started on the A • Rather than being followed and chased by The Winkies, Toto 13th, Richard Thorpe was—literally and figuratively—calling the shots. instead escaped through their ranks to leap across the castle $20.00 Rumor had it that the Oz Unit first would seek and photograph whichever drawbridge. California barnyard most resembled Kansas. Alternately, a trade paper re- • Thorpe kept Bolger, Ebsen, and Lahr in their Guard disguises well ported that all the musical numbers would be completed before other after they broke through The Tower Room door to free Dorothy. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Beverly Hillbillies: a Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968

Paul Henning; The Beverly Hillbillies: A Comedy in Three Acts; 9780871294111; 1968; Dramatic Publishing, 1968 The Beverly Hillbillies is an American situation comedy originally broadcast for nine seasons on CBS from 1962 to 1971, starring Buddy Ebsen, Irene Ryan, Donna Douglas, and Max Baer, Jr. The series is about a poor backwoods family transplanted to Beverly Hills, California, after striking oil on their land. A Filmways production created by writer Paul Henning, it is the first in a genre of "fish out of water" themed television shows, and was followed by other Henning-inspired country-cousin series on CBS. In 1963, Henning introduced Petticoat Junction, and in 1965 he reversed the rags The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 : A nouveau riche hillbilly family moves to Beverly Hills and shakes up the privileged society with their hayseed ways. The Beverly Hillbillies - Season 3 English Sub | Fmovies. Loading Turn off light Report. Loading ads You can also control the player by using these shortcuts Enter/Space M 0-9 F. Scroll down and click to choose episode/server you want to watch. - We apologize to all users; due to technical issues, several links on the website are not working at the moments, and re - work at some hours late. Watch The Beverly Hillbillies 3 Online. the beverly hillbillies 3 full movie with English subtitle. Stars: Buddy Ebsen, Donna Douglas, Raymond Bailey, Irene Ryan, Max Baer Jr, Nancy Kulp. "The Beverly Hillbillies" is a classic American comedy series that originally aired for nine seasons from 1962 to 1971 and was the first television series to feature a "fish out of water" genre. -

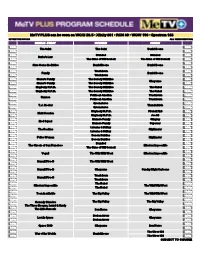

Ldim4-1620832776-Metv Plus 2Q21.Pdf

Daniel Boone MeTV PLUS can be seen on WCIU 26.5 • Xfinity 361 • RCN 30 • WOW 196 • Spectrum 188 EFFECTIVE 5/15/21 ALL TIMES CENTRAL MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00a 5:00a The Saint The Saint Daniel Boone 5:30a 5:30a 6:00a Branded Branded 6:00a Burke's Law 6:30a The Guns of Will Sonnett The Guns of Will Sonnett 6:30a 7:00a 7:00a Here Come the Brides Daniel Boone Daniel Boone 7:30a 7:30a 8:00a Trackdown 8:00a Family Daniel Boone 8:30a Trackdown 8:30a 9:00a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:00a Cheyenne 9:30a Mama's Family The Beverly Hillbillies 9:30a 10:00a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:00a 10:30a Mayberry R.F.D. The Beverly Hillbillies The Rebel 10:30a 11:00a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:00a Cannon 11:30a Petticoat Junction Trackdown 11:30a 12:00p Green Acres 12:00p T.J. Hooker Thunderbirds 12:30p Green Acres 12:30p 1:00p Mayberry R.F.D. Fireball XL5 1:00p Matt Houston 1:30p Mayberry R.F.D. Joe 90 1:30p 2:00p Mama's Family Stingray 2:00p Mod Squad 2:30p Mama's Family Supercar 2:30p 3:00p Laverne & Shirley 3:00p The Rookies Highlander 3:30p Laverne & Shirley 3:30p 4:00p Bosom Buddies 4:00p Police Woman Highlander 4:30p Bosom Buddies 4:30p 5:00p Branded 5:00p The Streets of San Francisco Mission: Impossible 5:30p The Guns of Will Sonnett 5:30p 6:00p 6:00p Vega$ The Wild Wild West Mission: Impossible 6:30p 6:30p 7:00p 7:00p Hawaii Five-O The Wild Wild West 7:30p 7:30p 8:00p 8:00p Hawaii Five-O Cheyenne Sunday Night Cartoons 8:30p 8:30p 9:00p Trackdown 9:00p Hawaii Five-O 9:30p Trackdown 9:30p 10:00p The -

Calendar of Events 2017 Board Meetings Website Upgrading

Monthly Newsletter for The Tiffany Homeowners Association • A Covenant Protected Community Calendar April 2017 Vol. 12 No. 04 • Circulation: 175 of Events 2017 Upgrading Telecom Lines April 15th: Easter Egg Hunt The Xfinity/Comcast folks are upgrading the Telecom lines from Dry Creek Road 10:30 a.m. In our park to Milwaukee for the Tiffany neighborhood. They are using a horizontal directional April 22nd: Park Clean-up Day drilling, (HDD) machine to drill 4-5 feet below the ground to install new cable and con- 9:00 a.m. In our park duit. The utility easement runs behind the houses and along the property lines between May 26-29: Dumpster Days houses. The contractor should request access before entering your yard or opening a gate. The City of Centennial has issued a building permit for these folks. Call the City June 3: Spring Walk Thru of Centennial if you have any concerns or questions. June 9-10: Annual Yard Sale — Tom Wood July 4th: 4th of July Parade Starts at Milwaukee Way/ Fillmore Circle Park Clean Up Day August 13th: Neighborhood Picnic 5 p.m. In our park & Plant Swap All residents are invited to park clean-up day on Saturday April 22 at 9 a.m. We can pull weeds, pick up trash and sticks, trim bushes, and more. Does your garden need a change this Spring? Bring your unwanted perennials to Board Meetings the park during clean-up day. Trade them for plants someone else brings. Or take some June 19: Board Meeting – 6:30 p.m. -

Available Videos for TRADE (Nothing Is for Sale!!) 1

Available Videos For TRADE (nothing is for sale!!) 1/2022 MOSTLY GAME SHOWS AND SITCOMS - VHS or DVD - SEE MY “WANT LIST” AFTER MY “HAVE LIST.” W/ O/C means With Original Commercials NEW EMAIL ADDRESS – [email protected] For an autographed copy of my book above, order through me at [email protected]. 1966 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS and NBC Fall Schedule Preview 1997 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS Fall Schedule Preview (not for trade) Many 60's Show Promos, mostly ABC Also, lots of Rock n Roll movies-“ROCK ROCK ROCK,” “MR. ROCK AND ROLL,” “GO JOHNNY GO,” “LET’S ROCK,” “DON’T KNOCK THE TWIST,” and more. **I ALSO COLLECT OLD 45RPM RECORDS. GOT ANY FROM THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES?** TV GUIDES & TV SITCOM COMIC BOOKS. SEE LIST OF SITCOM/TV COMIC BOOKS AT END AFTER WANT LIST. Always seeking “Dick Van Dyke Show” comic books and 1950s TV Guides. Many more. “A” ABBOTT & COSTELLO SHOW (several) (Cartoons, too) ABOUT FACES (w/o/c, Tom Kennedy, no close - that’s the SHOW with no close - Tom Kennedy, thankfully has clothes. Also 1 w/ Ben Alexander w/o/c.) ACADEMY AWARDS 1974 (***not for trade***) ACCIDENTAL FAMILY (“Making of A Vegetarian” & “Halloween’s On Us”) ACE CRAWFORD PRIVATE EYE (2 eps) ACTION FAMILY (pilot) ADAM’S RIB (2 eps - short-lived Blythe Danner/Ken Howard sitcom pilot – “Illegal Aid” and rare 4th episode “Separate Vacations” – for want list items only***) ADAM-12 (Pilot) ADDAMS FAMILY (1ST Episode, others, 2 w/o/c, DVD box set) ADVENTURE ISLAND (Aussie kid’s show) ADVENTURER ADVENTURES IN PARADISE (“Castaways”) ADVENTURES OF DANNY DEE (Kid’s Show, 30 minutes) ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY (8 Episodes, 4 w/o/c “Lapidary Wheel” “Gibraltar Toad,”“ Morocco,” “Homing Pigeon,” Others without commercials - “Sea Cucumber,” “Hawaiian Hamza,” “Dancing Mouse,” & “Wrong Rembrandt”) ADVENTURES OF LUCKY PUP 1950(rare kid’s show-puppets, 15 mins) ADVENTURES OF A MODEL (Joanne Dru 1956 Desilu pilot. -

Music in GUNSMOKE Half-Hour Series PART II

Music in GUNSMOKE Half-Hour Series PART II [all Season Six half-hour episodes] Next is the Gunsmoke Sixth Season, Volume One dvd... 1 2 Note than just slightly more than half of the music in the episodes of this season were original scores, including three by Bernard Herrmann, three by Goldsmith, three by Fred Steiner, two by Lyn Murray, etc. "Friend's Payoff" (September 3, 1960) *** C Original score by Lyn Murray. Synopsis: An old friend of Matt Dillon's that he hasn't seen in many years, Ab Butler, is shot. Mysteriously, a man named Joe Leeds (played by Tom Reese) enters Dodge to look for Ab Butler. Murray, Lyn. Gunsmoke. Friend's Payoff (ep). TV Series. Score no: CPN5918. FS. Format: OZM. Foreign Library : folders 3693-3703. Box 77. -#3694 "Speechless Lies" Take 3 (1:15) -00:23 thru 00:53 CBS cue #3693 "After Summer Merrily" Take 3, (00:35) 3 Scene: Chester is busy in the Marshal's office trying to fix an old chair. A small boy comes in with a written message, looking for the Marshal. -2:19 thru 3:34 CBS cue #3694 "Speechless Lies" Take 3 (1:15) Scene: The message is from Matt's old friend, Ab Butler, who says he was shot in the shot & needs help quick. Dillon on a horse & Chester in an open wagon go out to find him. -3:56 thru 4:44 Scene: Dissolve to Doc's office, being treated by Adams. Dillon starts to question Ab again. Note that I have no further info on this and following cues for this score. -

Excerpt from a Cuban in Mayberry

Interlude THE ROAD TO MAYBERRY Nobody's from no place. ANDY TAYLOR, " STRANGER IN TOWN" (1.1_2) HE DEBUT EPISODE OF THE ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW T was broadcast on October 3, 1960. Two weeks later, in Havana, my family's food wholesaling business-we called it el almacen, the warehouse-was confiscated by the Castro regime. A few days after that, on October 24, 1960, I left Cuba with my parents, my two brothers, and my sister on an overnight ferry to Key West called, of all things, The City of Havana. I was eleven years old. My parents were in their late thirties. That evening CBS broadcast the fourth epi sode of TAGS, "Ellie Comes to Town." It strikes me as fitting and a little eerie that as Ellie was settling into Mayberry, I was beginning my own road to the Friendly Town. The story of how I became an undocumented Mayberrian, the town's resident alien, began on that Monday. Like hundreds of thousands of other Cubans, we settled in Miami. Except that we didn't truly settle, since we were planning to return to Cuba to pick up where the island's turbulent history had left us off. We saw ourselves as people passing through, transients rather than settlers. Unlike immigrants, we didn't come to America looking for a better life. We had a good one in Cuba. America was a rest stop before we turned around and headed back home. The im migrant lives in the fast lane. He is in a hurry-in a hurry to get a job, learn the language, lay down roots. -

Crossroads Film and Television Program List

Crossroads Film and Television Program List This resource list will help expand your programmatic options for the Crossroads exhibition. Work with your local library, schools, and daycare centers to introduce age-appropriate books that focus on themes featured in the exhibition. Help libraries and bookstores to host book clubs, discussion programs or other learning opportunities, or develop a display with books on the subject. This list is not exhaustive or even all encompassing – it will simply get you started. Rural themes appeared in feature-length films from the beginning of silent movies. The subject matter appealed to audiences, many of whom had relatives or direct experience with life in rural America. Historian Hal Barron explores rural melodrama in “Rural America on the Silent Screen,” Agricultural History 80 (Fall 2006), pp. 383-410. Over the decades, film and television series dramatized, romanticized, sensationalized, and even trivialized rural life, landscapes and experiences. Audiences remained loyal, tuning in to series syndicated on non-network channels. Rural themes still appear in films and series, and treatments of the subject matter range from realistic to sensational. FEATURE LENGTH FILMS The following films are listed alphabetically and by Crossroads exhibit theme. Each film can be a basis for discussions of topics relevant to your state or community. Selected films are those that critics found compelling and that remain accessible. Identity Bridges of Madison County (1995) In rural Iowa in 1965, Italian war-bride Francesca Johnson begins to question her future when National Geographic photographer Robert Kincaid pulls into her farm while her husband and children are away at the state fair, asking for directions to Roseman Bridge. -

Body Lies in NY Armory

1 turn, tcapentu* tf. Partly dndy W^jr, Ufh la te Sfe, T*. BED BANK TODAY •ttt, ctatfy, dunw cf rfwwm, 23,600 tow M. Twawrsw, tetr, Ugh it *• Mt. ThaUty, Itii md CML tioaotmnitin-vn.mt Urn VMtfaer, ***• t DIAL 741-0010 Utatd «tu;. Ibn4u> Ihnash Fittir. SMOB« CUM Pwitp PAGE ONE VOL. 86, NO. 200 P«M tt tUd B4nk ul U Mdllloaai M*Uln» Otflet*. RED BANK, N. J., TUESDAY, APRIL 7, 1964 7c PER COPY GOP Maps Mac Arthur•« Go-It-Alone Fiscal Study Body Lies In TRENTON (AP) - The Republican majority of tha New Jersey Legislature has decided on a go-it-alone policy in setting up an economy study of state government. Republican leaders of the Senate and Assembly met yester- day and decided to reject Gov. Richard J. Hughes' suggestions about the study, made in a conditional veto last month. The N.Y. Armory decision also eliminates chances of a $50,000 appropriation (or the study commission, since the Democratic governor's ap- NEW YORK (AP)-A shriveled Washington after three major op- conflicts as World War I and II. proval ^s required for such spending. yet somehow majestic figure in erations. Yesterday the body lay at the Senate Majority Leader William E. Ozzard, R-Somerset, simple sun tan uniform lay in a Clergymen expected to pray at Universal Funeral Chapel, Lex- laid the commission would operate on funds scraped up from history-laden armory today, a the casket in the armory on Park ngton '.ve. and 52nd St., not far the Legislature's regular budget.