The New FCC Cross-Ownership Rules, 59 Marq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

1044 RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager CHAPTE ADA WJNZ 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sales RX• ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. GENERAL INFORMATION / STATISTICS of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. (616) 343-3200 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 669, 5310 N. -

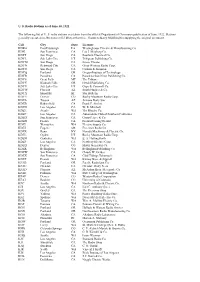

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) ) ) )

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC In the matter of: ) ) Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) MB Docket 13-249 ) ) COMMENTS OF REC NETWORKS One of the primary goals of REC Networks (“REC”)1 is to assure a citizen’s access to the airwaves. Over the years, we have supported various aspects of non-commercial micro- broadcast efforts including Low Power FM (LPFM), proposals for a Low Power AM radio service as well as other creative concepts to use spectrum for one way communications. REC feels that as many organizations as possible should be able to enjoy spreading their message to their local community. It is our desire to see a diverse selection of voices on the dial spanning race, culture, language, sexual orientation and gender identity. This includes a mix of faith-based and secular voices. While REC lacks the technical knowledge to form an opinion on various aspects of AM broadcast engineering such as the “ratchet rule”, daytime and nighttime coverage standards and antenna efficiency, we will comment on various issues which are in the realm of citizen’s access to the airwaves and in the interests of listeners to AM broadcast band stations. REC supports a limited offering of translators to certain AM stations REC feels that there is a segment of “stand-alone” AM broadcast owners. These owners normally fall under the category of minority, women or GLBT/T2. These owners are likely to own a single AM station or a small group of AM stations and are most likely to only own stations with inferior nighttime service, such as Class-D stations. -

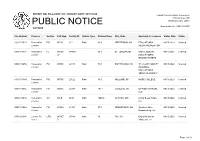

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-200917-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 09/17/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000113523 Renewal of FM WCVJ 612 Main 90.9 JEFFERSON, OH EDUCATIONAL 09/15/2020 Granted License MEDIA FOUNDATION 0000114058 Renewal of FL WSJB- 194835 96.9 ST. JOSEPH, MI SAINT JOSEPH 09/15/2020 Granted License LP EDUCATIONAL BROADCASTERS 0000116255 Renewal of FM WRSX 62110 Main 91.3 PORT HURON, MI ST. CLAIR COUNTY 09/15/2020 Granted License REGIONAL EDUCATIONAL SERVICE AGENCY 0000113384 Renewal of FM WTHS 27622 Main 89.9 HOLLAND, MI HOPE COLLEGE 09/15/2020 Granted License 0000113465 Renewal of FM WCKC 22183 Main 107.1 CADILLAC, MI UP NORTH RADIO, 09/15/2020 Granted License LLC 0000115639 Renewal of AM WILB 2649 Main 1060.0 CANTON, OH Living Bread Radio, 09/15/2020 Granted License Inc. 0000113544 Renewal of FM WVNU 61331 Main 97.5 GREENFIELD, OH Southern Ohio 09/15/2020 Granted License Broadcasting, Inc. 0000121598 License To LPD W30ET- 67049 Main 30 Flint, MI Digital Networks- 09/15/2020 Granted Cover D Midwest, LLC Page 1 of 62 REPORT NO. PN-2-200917-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 09/17/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 83, No. 5 ● November 30, 2015 ● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 13 … Musings of the Members 21 … Tower Calendar / DXtreme 5 … Domestic DX Digest West 14 … International DX Digest 22 … KC 2016 Call for Papers 9 … Domestic DX Digest East 17 … FCC CP Status Report 23 … Space Wx / FCC Silent List 2016 DXers Gathering: DXers in AM, FM, and Just FYI, as a nonprofit club run entirely by TV, including the NRC, IRCA, WTFDA, and uncompensated volunteers, NRC policy is not to DecaloMania will gather on September 9‐11, 2016 take advertising in DX News. However, we will in Kansas City, MO. It will be held at the Hyatt publish free announcements of commercial Place Kansas City Airport, 7600 NW 97th products that may be of interest to members – no Terrace. Information on registration will be made more than once a year, on a “space available” available starting in January. Rates are $99.00 per basis. Contact [email protected] for night for 1 to 3 persons per room, plus taxes and more info. fees. Plan to arrive on Thursday for 3 nights, and Membership Report we end Sunday at noon. Free airport transfers “Please renew my membership in the NRC for and breakfast each morning. Registration: $55 another year.” – Dave Bright. per person which includes a free Friday evening New Members: Welcome to Antoine Gamet, pizza party and Saturday evening banquet. Coatesville, PA; and Joseph Kremer, Bridgeport, Checks made payable to “National Radio Club” WV. and sent to Ernest J. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Hadiotv EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75C

DXer's DREAM THAT ALMOST WAS SHASILAND HadioTV EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75c BUILD COLD QuA BREE ... a 2-FET metal moocher to end the gold drain and De Gaulle! PIUS Socket -2 -Me CB Skyhook No -Parts Slave Flash Patrol PA System IC Big Voice www.americanradiohistory.com EICO Makes It Possible Uncompromising engineering-for value does it! You save up to 50% with Eico Kits and Wired Equipment. (%1 eft ale( 7.111 e, si. a er. ortinastereo Engineering excellence, 100% capability, striking esthetics, the industry's only TOTAL PERFORMANCE STEREO at lowest cost. A Silicon Solid -State 70 -Watt Stereo Amplifier for $99.95 kit, $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3070. A Solid -State FM Stereo Tuner for $99.95 kit. $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3200. A 70 -Watt Solid -State FM Stereo Receiver for $169.95 kit, $259.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3570. The newest excitement in kits. 100% solid-state and professional. Fun to build and use. Expandable, interconnectable. Great as "jiffy" projects and as introductions to electronics. No technical experience needed. Finest parts, pre -drilled etched printed circuit boards, step-by-step instructions. EICOGRAFT.4- Electronic Siren $4.95, Burglar Alarm $6.95, Fire Alarm $6.95, Intercom $3.95, Audio Power Amplifier $4.95, Metronome $3.95, Tremolo $8.95, Light Flasher $3.95, Electronic "Mystifier" $4.95, Photo Cell Nite Lite $4.95, Power Supply $7.95, Code Oscillator $2.50, «6 FM Wireless Mike $9.95, AM Wireless Mike $9.95, Electronic VOX $7.95, FM Radio $9.95, - AM Radio $7.95, Electronic Bongos $7.95. -

Pinconning Pittsford

Michigan Directory of Radio mgr, gen sls mgr & progmg dir; Randy Rowley, mus dir; Jim McKinney, pres & gen mgr; Jackie Gordon. natl sls mgr; Greg Marsh, rgnl sis class. Spec prog: Black one hr, Sp one hr wkly. *Robert Liggett, news dir; Todd Overhuel, pub affrs dir; Walker Sisson, chief of engrg. mgr; Tern Ray, progmg dir: Trisha Frey, mus dir; Dennis Murray, chief chmn; James A. Jensen, pros: Lawrence C. Smith. gen mgr; Scott of engrg. Shigley, gen sls mgr; Jim McKenzie, progmg dir; Bill Gilmer. news dir; Ovid -Elsie Bill Sanderson, chief of engrg. WLXT(FM)-Listing follows WMBN WSAG(FM)-Co-owned with WHLS(AM). Aug 7, 1964: 107.1 mhz; 6 WVOES(FM)- Mar 21, 1978: 91.3 mhz; 553 w. 140 ft. TL: N43 02 44 kw. 298 ft. TL: N42 58 37 W82 27 52. Stereo. Hm opn: 24. Web Site: WMIBN(AM)- May 1946: 1340 khz; 1 kw -U. TL: N45 20 50 W84 58 W84 23 14. Stereo. Hrs opn: 24. 8989 Colony Rd., Elsie (48831). www.wsaq@net. Format: Country. Target aud: 25 -55. Brian Harper, 01. Hrs opn: 24. Box 286 (49770). 2095 U.S. 131 S. (49770). (231) (989) 834 -2271. Fax: (989) 862 -4463. Licensee: Ovid -Elsie Area progmg dir; Bob Pouget, mus dir. 347 -8713. Fax: (231) 347 -9920. Licensee: MacDonald Garber Schools. (acq 1978) Format: Polka. Spec prog: Class one hr, Pol one Broadcasting Inc. (group owner; acq 11- 17 -98; grpsl) Rep: D & R hr, Czech one hr, stage & screen one hr wkly. George Bishop, gen WHLX(AM)-(Manne City). -

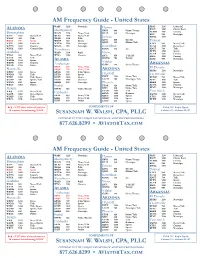

AM Radio Guide Version 1.4 For

AM Frequency Guide - United States LABAMA WABF 1220 Nostalgia Homer KISO 1230 Urban AC A KSLX 1440 Classic Rock Montgomery KBBI 890 News/Variety KCWW 1580 Country Birmingham WACV 1170 News/Talk KGTL 620 Nostalgia KOY 550 Nostalgia WAPI 1070 News/Talk WLWI 1440 News/Talk KMYL 1190 WERC 960 Talk WIQR 1410 Talk Juneau WJOX 690 Sports WMSP 740 Sports KINY 800 Hot AC Tucson WJLD 1400 Urban AC WTLM 1520 Nostalgia KJNO 630 Oldies/Talk KTKT 990 News/Talk WFHK 1430 Country WNZZ 950 Nostalgia Ketchikan KUAT 1550 News/Jazz WPYK 1010 Country Olds Tuscaloosa KTKN 930 AC KNST 790 Talk KFFN 1490 Sports Gadsden WAJO 1310 R&B Nome KCUB 1290 Country WNSI 810 News/Talk WVSA 1380 Country KICY 850 Talk/AC KHIL 1250 Country WAAX 570 Talk KNOM 780 Variety KSAZ 580 Nostalgia WHMA 1390 Sports ALASKA WZOB 1250 Country Valdez ARKANSAS WGAD 1350 Oldies Anchorage KCHU 770 News/Variety KENI 650 News/Talk El Dorado Huntsville KFQD 750 News/Talk ARIZONA KDMS 1290 Nostalgia WBHP 1230 News KBYR 700 Talk/Sports WVNN 770 Talk KTZN 550 Sports Flagstaff Fayetteville WTKI 1450 Talk/Sports KAXX 1020 Sports KYET 1180 News/Talk KURM 790 News/Talk WUMP 730 Sports/Talk KASH 1080 Classical KAZM 780 Nostalgia/Talk KFAY 1030 Talk WZNN 620 Sports KHAR 590 Nostalgia Phoenix KREB 1390 Sports WKAC 1080 Oldies Bethel KTAR 620 News/Talk KUOA 1290 Country KESE 1190 Nostalgia Mobile KYUK 640 News/Variety KFYI 910 News/Talk WKSJ 1270 News/Talk KXAM 1310 Talk Fort Smith WABB 1480 News/Sports Fairbanks KFNN 1510 Business KWHN 1320 News/Talk WHEP 1310 Talk KFAR 660 News/Talk KDUS 1060 Sports KTCS 1410 Country KIAK 970 News/Talk WBCA 1110 Country Olds KGME 1360 Sports KFPW 1230 Nostalgia KCBF 820 Oldies KMVP 860 Sports Red = FCC clear channel stations COMPLIMENTS OF AM & HF Radio Guide & stations broadcasting 50 KW SUSANNAH W. -

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager ADA WJNZ(AM) 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sls. ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. RADIO STATIONS INMICHIGAN RADIO STATIONS (616) 343-1717 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 665, 5310 N. -

Freq Call State Location U D N C Distance Bearing

AM BAND RADIO STATIONS COMPILED FROM FCC CDBS DATABASE AS OF FEB 6, 2012 POWER FREQ CALL STATE LOCATION UDNCDISTANCE BEARING NOTES 540 WASG AL DAPHNE 2500 18 1107 103 540 KRXA CA CARMEL VALLEY 10000 500 848 278 540 KVIP CA REDDING 2500 14 923 295 540 WFLF FL PINE HILLS 50000 46000 1523 102 540 WDAK GA COLUMBUS 4000 37 1241 94 540 KWMT IA FORT DODGE 5000 170 790 51 540 KMLB LA MONROE 5000 1000 838 101 540 WGOP MD POCOMOKE CITY 500 243 1694 75 540 WXYG MN SAUK RAPIDS 250 250 922 39 540 WETC NC WENDELL-ZEBULON 4000 500 1554 81 540 KNMX NM LAS VEGAS 5000 19 67 109 540 WLIE NY ISLIP 2500 219 1812 69 540 WWCS PA CANONSBURG 5000 500 1446 70 540 WYNN SC FLORENCE 250 165 1497 86 540 WKFN TN CLARKSVILLE 4000 54 1056 81 540 KDFT TX FERRIS 1000 248 602 110 540 KYAH UT DELTA 1000 13 415 306 540 WGTH VA RICHLANDS 1000 97 1360 79 540 WAUK WI JACKSON 400 400 1090 56 550 KTZN AK ANCHORAGE 3099 5000 2565 326 550 KFYI AZ PHOENIX 5000 1000 366 243 550 KUZZ CA BAKERSFIELD 5000 5000 709 270 550 KLLV CO BREEN 1799 132 312 550 KRAI CO CRAIG 5000 500 327 348 550 WAYR FL ORANGE PARK 5000 64 1471 98 550 WDUN GA GAINESVILLE 10000 2500 1273 88 550 KMVI HI WAILUKU 5000 3181 265 550 KFRM KS SALINA 5000 109 531 60 550 KTRS MO ST. LOUIS 5000 5000 907 73 550 KBOW MT BUTTE 5000 1000 767 336 550 WIOZ NC PINEHURST 1000 259 1504 84 550 WAME NC STATESVILLE 500 52 1420 82 550 KFYR ND BISMARCK 5000 5000 812 19 550 WGR NY BUFFALO 5000 5000 1533 63 550 WKRC OH CINCINNATI 5000 1000 1214 73 550 KOAC OR CORVALLIS 5000 5000 1071 309 550 WPAB PR PONCE 5000 5000 2712 106 550 WBZS RI