Identifying Lewis Carroll's Alice Through Celtic Mythology the Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death-Tales of the Ulster Heroes

ffVJU*S )UjfáZt ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV KUNO MEYER, Ph.D. THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO. LTD. LONDON: WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 (Reprinted 1937) cJ&íc+u. Ity* rs** "** ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV. KUNO MEYER THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO., Ltd, LONDON : WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 °* s^ B ^N Made and Printed by the Replika Process in Great Britain by PERCY LUND, HUMPHRIES &f CO. LTD. 1 2 Bedford Square, London, W.C. i and at Bradford CONTENTS PAGE Peeface, ....... v-vii I. The Death of Conchobar, 2 II. The Death of Lóegaire Búadach . 22 III. The Death of Celtchar mac Uthechaib, 24 IV. The Death of Fergus mac Róich, . 32 V. The Death of Cet mac Magach, 36 Notes, ........ 48 Index Nominum, . ... 46 Index Locorum, . 47 Glossary, ....... 48 PREFACE It is a remarkable accident that, except in one instance, so very- few copies of the death-tales of the chief warriors attached to King Conchobar's court at Emain Macha should have come down to us. Indeed, if it were not for one comparatively late manu- script now preserved outside Ireland, in the Advocates' Library, Edinburgh, we should have to rely for our knowledge of most of these stories almost entirely on Keating's History of Ireland. Under these circumstances it has seemed to me that I could hardly render a better service to Irish studies than to preserve these stories, by transcribing and publishing them, from the accidents and the natural decay to which they are exposed as long as they exist in a single manuscript copy only. -

Lewis Carroll: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND by Lewis Carroll with fourty-two illustrations by John Tenniel This book is in public domain. No rigths reserved. Free for copy and distribution. This PDF book is designed and published by PDFREEBOOKS.ORG Contents Poem. All in the golden afternoon ...................................... 3 I Down the Rabbit-Hole .......................................... 4 II The Pool of Tears ............................................... 9 III A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale .................................. 14 IV The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill ................................. 19 V Advice from a Caterpillar ........................................ 25 VI Pig and Pepper ................................................. 32 VII A Mad Tea-Party ............................................... 39 VIII The Queen’s Croquet-Ground .................................... 46 IX The Mock Turtle’s Story ......................................... 53 X The Lobster Quadrille ........................................... 59 XI Who Stole the Tarts? ............................................ 65 XII Alice’s Evidence ................................................ 70 1 Poem All in the golden afternoon Of wonders wild and new, Full leisurely we glide; In friendly chat with bird or beast – For both our oars, with little skill, And half believe it true. By little arms are plied, And ever, as the story drained While little hands make vain pretence The wells of fancy dry, Our wanderings to guide. And faintly strove that weary one Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour, To put the subject by, Beneath such dreamy weather, “The rest next time –” “It is next time!” To beg a tale of breath too weak The happy voices cry. To stir the tiniest feather! Thus grew the tale of Wonderland: Yet what can one poor voice avail Thus slowly, one by one, Against three tongues together? Its quaint events were hammered out – Imperious Prima flashes forth And now the tale is done, Her edict ‘to begin it’ – And home we steer, a merry crew, In gentler tone Secunda hopes Beneath the setting sun. -

Celtic Solar Goddesses: from Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven

CELTIC SOLAR GODDESSES: FROM GODDESS OF THE SUN TO QUEEN OF HEAVEN by Hayley J. Arrington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Women’s Spirituality Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California June 8, 2012 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this thesis: ________________________________________________ __________________ Judy Grahn, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ __________________ Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Copyright © Hayley Jane Arrington 2012 All Rights Reserved Formatted according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition ii Abstract Celtic Solar Goddesses: From Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven by Hayley J. Arrington Utilizing a feminist hermeneutical inquiry, my research through three Celtic goddesses—Aine, Grian, and Brigit—shows that the sun was revered as feminine in Celtic tradition. Additionally, I argue that through the introduction and assimilation of Christianity into the British Isles, the Virgin Mary assumed the same characteristics as the earlier Celtic solar deities. The lands generally referred to as Celtic lands include Cornwall in Britain, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Brittany in France; however, I will be limiting my research to the British Isles. I am examining these three goddesses in particular, in relation to their status as solar deities, using the etymologies of their names to link them to the sun and its manifestation on earth: fire. Given that they share the same attributes, I illustrate how solar goddesses can be equated with goddesses of sovereignty. Furthermore, I examine the figure of St. -

Irish Studies Around the World – 2020

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 16, 2021, pp. 238-283 https://doi.org/10.24162/EI2021-10080 _________________________________________________________________________AEDEI IRISH STUDIES AROUND THE WORLD – 2020 Maureen O’Connor (ed.) Copyright (c) 2021 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Introduction Maureen O’Connor ............................................................................................................... 240 Cultural Memory in Seamus Heaney’s Late Work Joanne Piavanini Charles Armstrong ................................................................................................................ 243 Fine Meshwork: Philip Roth, Edna O’Brien, and Jewish-Irish Literature Dan O’Brien George Bornstein .................................................................................................................. 247 Irish Women Writers at the Turn of the 20th Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives Edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney Deirdre F. Brady ..................................................................................................................... 250 English Language Poets in University College Cork, 1970-1980 Clíona Ní Ríordáin Lucy Collins ........................................................................................................................ 253 The Theater and Films of Conor McPherson: Conspicuous Communities Eamon -

On Program and Abstracts

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & MASARYK UNIVERSITY, BRNO, CZECH REPUBLIC TENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY TIME AND MYTH: THE TEMPORAL AND THE ETERNAL PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 26-28, 2016 Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic Conference Venue: Filozofická Fakulta Masarykovy University Arne Nováka 1, 60200 Brno PROGRAM THURSDAY, MAY 26 08:30 – 09:00 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:00 – 09:30 OPENING ADDRESSES VÁCLAV BLAŽEK Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA; IACM THURSDAY MORNING SESSION: MYTHOLOGY OF TIME AND CALENDAR CHAIR: VÁCLAV BLAŽEK 09:30 –10:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography & European University, St. Petersburg, Russia OLD WOMAN OF THE WINTER AND OTHER STORIES: NEOLITHIC SURVIVALS? 10:00 – 10:30 WIM VAN BINSBERGEN African Studies Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands 'FORTUNATELY HE HAD STEPPED ASIDE JUST IN TIME' 10:30 – 11:00 LOUISE MILNE University of Edinburgh, UK THE TIME OF THE DREAM IN MYTHIC THOUGHT AND CULTURE 11:00 – 11:30 Coffee Break 11:30 – 12:00 GÖSTA GABRIEL Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany THE RHYTHM OF HISTORY – APPROACHING THE TEMPORAL CONCEPT OF THE MYTHO-HISTORIOGRAPHIC SUMERIAN KING LIST 2 12:00 – 12:30 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia CULTIC CALENDAR AND PSYCHOLOGY OF TIME: ELEMENTS OF COMMON SEMANTICS IN EXPLANATORY AND ASTROLOGICAL TEXTS OF ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA 12:30 – 13:00 ATTILA MÁTÉFFY Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey & Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, -

Extracts on Eggs, Nymphs and Adult Red Spider Mites, Tetranychus Spp. (Acari: Tetranychidae) on Tomatoes

African Journal of Agricultural Research Vol.8(8), pp. 695-700, 8 March, 2013 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJAR DOI: 10.5897/AJAR12.2143 ISSN 1991-637X ©2013 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Efficacy of Syringa (Melia Azedarach L.) extracts on eggs, nymphs and adult red spider mites, Tetranychus spp. (Acari: Tetranychidae) on tomatoes Mwandila N. J. K.1, J. Olivier1*, D. Munthali2 and D. Visser3 1Department of Environmental Sciences, University of South Africa (UNISA), Florida 1710, South Africa. 2Department of Crop Science and Production, Botswana College of Agriculture, Private Bag 0027, Gaborone, Botswana. 3ARC-Roodeplaat Vegetable and Ornamental Plant Institute (VOPI), Private Bag X293, Pretoria 0001, South Africa. Accepted 18 February, 2013 This study evaluated the effect of Syringa (Melia azedarach) fruit and seed extracts (SSE) on red spider mite (Tetranychus spp.) eggs, nymphs and adults. Bioassay investigations were carried at the Vegetable and Ornamental Plant Institute (VOPI) outside Pretoria in South Africa using different concentrations (0.1, 1, 10, 20, 50, 75 and 100%) of SSE. Mortalities were measured at 24, 48 and 72 h after treatment and compared to the effects of the synthetic acaricides: Abamectin, chlorfenapyr and protenofos. A completely randomized design (CRD) was used with 12 treatments. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for effects of treatments. Differences in treatment means were identified using Fisher’s protected t-test least significant difference (LSD) at the 1% level of significance. Data were analysed using the statistical program GenStat (2003). The result of the analyses revealed that the efficacy of SSE and commercial synthetic acaricides increased with exposure time. -

'Jaws'. In: Hunter, IQ and Melia, Matthew, (Eds.) the 'Jaws' Book : New Perspectives on the Classic Summer Blockbuster

This is the accepted manuscript version of Melia, Matthew [Author] (2020) Relocating the western in 'Jaws'. In: Hunter, IQ and Melia, Matthew, (eds.) The 'Jaws' book : new perspectives on the classic summer blockbuster. London, U.K. For more details see: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/the-jaws-book-9781501347528/ 12 Relocating the Western in Jaws Matthew Melia Introduction During the Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium1 Carl Gottlieb, the film’s screenwriter, refuted the suggestion that Jaws was a ‘Revisionist’ or ‘Post’ Western, and claimed that the influence of the Western genre had not entered the screenwriting or production processes. Yet the Western is such a ubiquitous presence in American visual culture that its narratives, tropes, style and forms can be broadly transposed across a variety of non-Western genre films, including Jaws. Star Wars (1977), for instance, a film with which Jaws shares a similar intermedial cultural position between the Hollywood Renaissance and the New Blockbuster, was a ‘Western movie set in Outer Space’.2 Matthew Carter has noted the ubiquitous presence of the frontier mythos in US popular culture and how contemporary ‘film scholars have recently taken account of the “migration” of the themes of frontier mythology from the Western into numerous other Hollywood genres’.3 This chapter will not claim that Jaws is a Western, but that the Western is a distinct yet largely unrecognised part of its extensive cross-generic hybridity. Gottlieb has admitted the influence of the ‘Sensorama’ pictures of proto-exploitation auteur William Castle (the shocking appearance of Ben Gardner’s head is testament to this) as well as The Thing from Another World (1951),4 while Spielberg suggested that they were simply trying to make a Roger Corman picture.5 Critical writing on Jaws has tended to exclude the Western from the film’s generic DNA. -

Melia-Ebrochure.Pdf

SOHNA - THE BEST OF SUBURBIA AND THE CITY Sohna or South Gurgaon is an Idyllic retreat with sulphur water Springs , Scenic Lake and a charming bird scantury, just a stone throw away. South of Gurgaon offers you the luxury of living in a chaos-free environment – while enjoying Gurgaon's best amenities at an affordable price compared to Gurgaon. South of Gurgaon is well connected to Gurgaon and the National Capital by the National Highway 248A which will also soon be revamped to a 6 Lane highway. The areas around the Gurgaon Sohna highway is set to emerge as the next axis of industrial and commercial development like Manesar. The Haryana State Industrial & Infrastructure Development Corporation (HSIIDC) has acquired about 1,700 acres of land in Roz Ka Meo, nearly 26 km from Gurgaon, to establish a new industrial township on the lines of IMT Manesar. It will be well connected by the in-progress KMP (Kundli-Manesar-Palwal) and DMIC (Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor). Coming to localized connectivity, Sohna has a proposed 60 meter wide sector road that connects 5 sectors of Sohna. It will also have a 2 km elevated road between Vatika City and Badshahpur. South of Gurgaon, is also rapidly accessible from Udyog Vihar, Cyber City, IFFCO Chowk, Rajeev Chowk, NH8, Subhash Chowk and Hero Honda Chowk. Infrastructure South of Gurgaon has many other important facilities already in place – like banks, ATMs, shops for daily needs, nearby – all of which make living here extremely convenient. Hospitals like Medanta, Artemis, Paras, Fortis, Max, etc. are also located within 25-30 minutes. -

BRT Past Schedule 2016

Join Our Mailing List! 2016 Schedule current schedule 2015 past schedule 2014 past schedule 2013 past schedule 2012 past schedule 2011 past schedule 2010 past schedule 2009 past schedule JANUARY 2016 NOTE: If a show at BRT has an advance price & a day-of-show price it means: If you pre-pay OR call in your reservation any time before the show date, you get the advance price. If you show up at the door with no reservations OR call in your reservations on the day of the show, you will pay the day of show price. TO MAKE RESERVATIONS, CALL BRT AT: 401-725-9272 Leave your name, number of tickets desired, for which show, your phone number and please let us know if you would like a confirmation phone call. Mondays in January starting Jan. 4, $5.00 per class, 6:30-7:30 PM ZUMBA CLASSES WITH APRIL HILLIKER Thursday, January 7 5:00-6:00 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog 'NOG' TROUPE with Erika Damiani begins 6:00-7:00 PM: 8-week class SOFT SHOE TECHNIQUE with Erika Damiani begins 7:00-8:00 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog GREEN TROUPE (performance troupe) with Erika Damiani begins Friday, January 8 4:30-5:30 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog RINCE TROUPE with Erika Damiani begins 5:30-6:30 PM: 8-week class BEGINNER/ADVANCED BEGINNER HARD SHOE with Erika Damiani begins 6:30-7:30 PM: 8-week class SOFT SHOE TECHNIQUE with Erika Damiani begins 7:30-8:30 PM: 8-week class Tir Na Nog CEOL TROUPE with Erika Damiani begins Saturday, January 9 9:00 AM: 8-week class in BEGINNER IRISH STEP DANCE for children 5-10 with Erika Damiani begins 10:00 AM: 8-week class in CONTINUING -

Alice in Wonderland

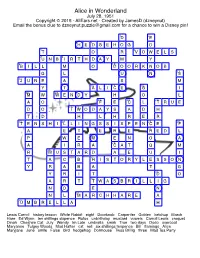

Alice in Wonderland July 28, 1951 Copyright © 2015 - AllEars.net - Created by JamesD (dzneynut) Email the bonus clue to [email protected] for a chance to win a Disney pin! 1 2 D E 3 4 H E D G E H O G D 5 6 T O R V O W E L S 7 8 U N B I R T H D A Y M Y 9 10 B I L L M O D O O R K N O B 11 G L U N S 12 J U N E A S M 13 14 15 Y T A L I C E G I 16 17 M W W E N D Y H O L 18 19 20 A O F E C L T R U E 21 22 D O T W O D A Y S A D H T D H L H R E R 23 24 25 26 T E N S H I L L I N G S S I X P E N C E F 27 A E T E R E R E D L 28 P W E M E N O A 29 A I R A C A T Q M 30 R M U S T A R D A E U I 31 T A C B H I S T O R Y L E S S O N Y R A B A T G 32 Y R I T D O 33 A R T T W A S B R I L L I G N O E N 34 N L M A R C H H A R E A 35 U M B R E L L A H Lewis Carroll history lesson White Rabbit eight Doorknob Carpenter Golden ketchup March Hare Ed Wynn ten shillings sixpence Rufus unbirthday mustard vowels Carroll Lewis croquet Dinah Cheshire Cat July Wendy Im Late umbrella smirk True two days Dodo overcoat Maryanne Tulgey Woods Mad Hatter cat red six shillings tenpence Bill flamingo Alice Maryjane June smile False bird hedgehog Dormouse Twas Brillig three Mad Tea Party ★ Thurl Ravenscroft, a member of the singing group, the Mellomen, who sing #27 Across, appears to have lost his head while singing a familiar song in what popular theme park attraction? (2 words) [HAUNTEDMANSION] Across Down 3. -

White Rabbit (1967) Jefferson Airplane

MUSC-21600: The Art of Rock Music Prof. Freeze White Rabbit (1967) Jefferson Airplane LISTEN FOR • Surrealistic lyrics • Spanish inflections • Musical ambition contained in pop AABA form • Overarching dramatic arc (cf. Ravel’s Bolero?) CREATION Songwriters Grace Slick Album Surrealistic Pillow Label RCA Victor 47-9248 (single); LSP-3766 (stereo album) Musicians Electric guitars, bass, drums, vocals Producer Rick Jarrard Recording November 1966; stereo Charts Pop 8; Album 3 MUSIC Genre Psychedelic rock Form AABA Key F-sharp Phrygian mode Meter 4/4 LISTENING GUIDE Time Form Lyric Cue Listen For 0:00 Intro (12) • Bass guitar and snare drum suggest the Spanish bolero rhythm. • Phrygian mode common in flamenco music. • Winding guitar lines evoke Spanish music. • Heavy reverb in all instruments save drums. MUSC-21600 Listening Guide Freeze “White Rabbit” (Jefferson Airplane, 1967) Time Form Lyric Cue Listen For 0.28 A (12) “One pill makes you” • Vocals enter quietly and with echo, with only bass, guitar, and snare drum accompaniment. 0:55 A (12) “And if you go” • Just a little louder and more forceful. 1:23 B (12) “When men on” • Music gains intensity: louder dynamic, second guitar, drums with more traditional rock beat. 1:42 A (21) “Go ask Alice” • Vocal now much more forceful. • Accompaniment more insistent, especially rhythm guitar. • Drives to climax at end. LYRICS One pill makes you larger When the men on the chessboard And one pill makes you small Get up and tell you where to go And the ones that mother gives you And you’ve just had some -

Place-Based Social Movements, Learning, and Prefiguration of Other Worlds

In the Breath of Learning: Place-based social movements, Learning, and Prefiguration of Other Worlds By Rainos Mutamba A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social Justice Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Rainos Mutamba 2018 In the Breath of Learning: Place-based social movements, Learning, and Prefiguration of Other Worlds Rainos Mutamba Doctor of Philosophy Social Justice Education University of Toronto 2018 Abstract Social movements have been and continue to be an integral part of the lifeworld as they create and promote conditions for the transformation of micro and macro aspects of socio-ecological relationships. From the vantage point of the present, we can argue that it is through the work and agitation of feminist, civil rights, LGBTQ, anti-colonial, socialist and environmentalist social movements (among others) that we have experienced socially just changes around the world. The study of social movements is therefore critical for learning about the knowledge-practices necessary to achieve socially just change. This project sought to explore, understand and conceptualize the epistemic ecologies of place- based social movements whose work centers the construction of urgently needed life-affirming human knowledge-practices. Specifically, it sought to illuminate on the scarcely studied connections among learning, knowledge, and society, by examining the social construction of reality in the context of social movement action. ii The flesh and blood of the project come from the work of social actors in Kufunda Learning Movement and my organizing with Ubuntu Learning Village. The study found that in these contexts, social movement actors are learning and constructing emancipatory knowledge- practices through their engagement with place-based social action.