Gender Talk in Neo-Hindu Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

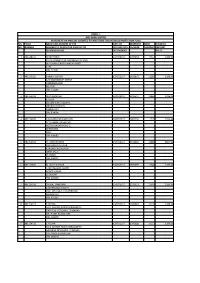

MEL Unclaimed Dividend Details 2010-2011 28.07.2011

MUKAND ENGINEERS LIMITED FINAL FOLIO DIV. AMT. NAME FATHERS NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE IEFP Trns. Date IN30102220572093 48.00 A BHASKER REDDY A ASWATHA REDDY H NO 1 1031 PARADESI REDDY STREET NR MARUTHI THIYOTOR PULIVENDULA CUDDAPAH 516390 03-Aug-2017 A000006 60.00 A GAFOOR M YUSUF BHAIJI M YUSUF 374 BAZAR STREET URAN 400702 03-Aug-2017 A001633 22.50 A JANAKIRAMAN G ANANTHARAMA KRISHNAN 111 H-2 BLOCK KIWAI NAGAR KANPUR 208011 03-Aug-2017 A002825 7.50 A K PATTANAIK A C PATTANAIK B-1/11 NABARD NAGAR THAKUR COMPLEX KANDIVLI E BOMBAY 400101 03-Aug-2017 A000012 12.00 A KALYANARAMAN M AGHORAM 91/2 L I G FLATS I AVENUE ASHOK NAGAR MADRAS 600083 03-Aug-2017 A002573 79.50 A KARIM AHMED PATEL AHMED PATEL 21 3RD FLR 30 NAKODA ST BOMBAY 400003 03-Aug-2017 A000021 7.50 A P SATHAYE P V SATHAYE 113/10A PRABHAT RD PUNE 411004 03-Aug-2017 A000026 12.00 A R MUKUNDA A G RANGAPPA C/O A G RANGAPPA CHICKJAJUR CHITRADURGA DIST 577523 03-Aug-2017 1201090001143767 150.00 A.R.RAJAN . A.S.RAMAMOORTHY 4/116 SUNDAR NAGARURAPULI(PO) PARAMAKUDI. RAMANATHAPURAM DIST. PARAMAKUDI. 623707 03-Aug-2017 A002638 22.50 ABBAS A PALITHANAWALA ASGER PALITHANAWALA 191 ABDUL REHMAN ST FATEHI HOUSE 5TH FLR BOMBAY 400003 03-Aug-2017 A000054 22.50 ABBASBHAI ADAMALI BHARMAL ADAMLI VALIJI NR GUMANSINHJI BLDG KRISHNAPARA RAJKOT GUJARAT 360001 03-Aug-2017 A000055 7.50 ABBASBHAI T VOHRA TAIYABBHAI VOHRA LOKHAND BAZAR PATAN NORTH GUJARAT 384265 03-Aug-2017 A006583 4.50 ABDUL AZIZ ABDUL KARIM ABDUL KARIM ECONOMIC INVESTMENTS R K SHOPPING CENTRE SHOP NO 6 S V ROAD SANTACRUZ W BOMBAY 400054 03-Aug-2017 A002095 60.00 ABDUL GAFOOR BHAIJI YUSUF 374 BAZAR ROAD URAN DIST RAIGAD 400702 03-Aug-2017 A000057 15.00 ABDUL HALIM QUERESHI ABDUL KARIM QUERESHI SHOP NO 1 & 2 NEW BBY SHOPPPING CET JUHU VILE PARLE DEVLOPEMENT SCHEME V M RD VILE PARLE WEST BOMBAY 400049 03-Aug-2017 IN30181110055648 15.00 ABDUL KAREEM K. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

NEO-HINDU MOVEMENTS BIBLIOGRAPHY of SAHAJA YOGA MOVEMENT (Founder: Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi / Nirmala Srivastava)

NEO-HINDU MOVEMENTS BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SAHAJA YOGA MOVEMENT (Founder: Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi / Nirmala Srivastava) Official websites: https://www.sahajayoga.org/ http://www.adishakti.org/ https://www.amruta.org/ https://sahajaworldfoundation.org/ ; http://shrimataji.org/ http://www.sahajvidya.org.uk/ https://www.nirmalavidya.org/ http://nirmalvidya.blogspot.com/ https://www.divinecoolbreeze.com/all-books http://sahajayogaencyclopedia.org/ https://sahaj-az.blogspot.com/ http://www.sakshi.org/ http://www.freemeditation.com/ http://www.researchingmeditation.org/ http://www.researchingmeditation.org/interesting-articles/sahaja-yoga https://www.onlinemeditation.org/ http://www.nirmalbhakti.com/ www.poetry-enlightened.org https://soundcloud.com/sahaja-library/ https://sahajayogamusic.com/ http://library.sahajaworld.org/ https://www.sahajaculture.org/ http://sahajayogaonline.3dcartstores.com/ http://sahaja-yoga-facts.com/ http://www.thelifeeternaltrust.org/ http://www.nirmaldham.org/ ; https://www.sahajayogamumbai.org/nirmal-dham-delhi/ http://www.sahajayoga.ro/ http://www.realizareasinelui.ro/ Devotional sources Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, Sahaja Yoga and Its Practice, New Delhi, The Life Eternal Trust, 1979. Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, Sahaja Yoga a Unique Discovery, Calcutta, /s.n./, 1990. Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, Sahaja Yoga, /Bombay/, /Vishwa Nirmala Dharma/, 1991. Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, Meta Modern Era, First Edition, /Pune/, /Vishwa Nirmala Dharma/, 1995 (Second edition, Bombay, Computex Graphics, 1996). Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, Cabella 94, /Vienna/, /Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi and Life Eternal Trust/, 1995 (Photographs by Michael Markl). Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, The Book of Adi Shakti, /s.l./, Nirmala Vidya LLC, 2013, ISBN 978-8897196075. (The book compiles the authorʼs earliest known writings. See also: https://mothersfirstbook.blogspot.com/). Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, Journey Within: The Final Steps to Self-Realization (The Words of Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi), Edited by Richard Payment, /s.l./, DCB Books, 2018, ISBN 978-1-387-54016-7 (First edition in 2012). -

Keltie Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) Avenida De Europa, 4 E-03008 Alicante SPAIN

Keltie Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) Avenida de Europa, 4 E-03008 Alicante SPAIN 29 July 2011 Courier Attention: Monica Gimenez Hernandez Dear Sirs Community Trade Mark Registration No 1224831 OSHO in the name of Osho International Foundation and Application for invalidation No 5064C by Osho Lotus Commune e.V. Our Reference: S26653/RAC Further to OHIM's letter of 8 March 2011, we make the following submissions in response to the above Application for Invalidity filed by Osho Lotus Commune e.V. against Registration No 1224831 for the mark OSHO. Initial Observations In support of our submissions, we include a main Witness Statement by Klaus Steeg and Exhibits KS1 to KS 96 and supporting Witness Statements by Michael Byrne, Ursula Hoess, Klaus-Peter Creutzfeldt, Thomas Forsberg, Philip Toelkes, John Andrews and Ronald S Tanner. These Witness Statements and the evidence attached thereto prove that the Applicant's submissions are misleading and erroneous. Moreover, the evidence submitted by the Applicant consists in the most part of evidence of genuine use of the Registered Proprietor's own mark. It is submitted that the Application for Invalidation has been filed with malicious intent by the individual behind the Applicant company consistent with his ongoing attempts to destroy the work of the Registered Proprietor's foundation and to bring its copyright and the OSHO trade mark into disrepute. The OSHO trade mark has been in use by the Registered Proprietor for over 21 years since 1989 and therefore, the application to cancel this CTM has incurred the Registered Proprietor in an enormous amount of time and expense in searching through the archives for evidence to prove that the mark is validly registered. -

“There Can Be No Peace in the World Until There Is Peace Within

There can “be no peace in the world until there is peace within Nirmala Srivastava, better known as Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, once said, “There can 1923 to 1970 – The first 47 years be no peace in the world until there is peace Born on March 21, 1923 in Chindwara, India, to a Christian family, within.” She was born with peace within and Nirmala Salve emerged from the womb absolutely clean, without a trace of blood upon her tiny infant body. She was given the name spent her long and influential life sharing Nirmala, which means immaculate, by her parents Prasad and it with others. While she experienced and Cornelia Salve, direct descendants of the royal Shalivahana dynasty and personal friends of Mahatma Gandhi. achieved more in her first 47 years than Nirmala, or Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi as she later came to be known, many of us do in an entire lifetime, it is possessed exceptional wisdom and compassion from an early age. the achievements of her final 40 years She and her family were residents of Gandhi’s ashram for several years of her childhood, and Gandhi recognized the unique spiritual that cause many to regard her as the most gifts within her. Though she was just a child, he consulted her on significant spiritual figure of our time. many matters, including how to pray and the best order for daily prayers in the ashram. Though February 23, 2011 marked the end Shri Mataji fully embraced her gift for leadership during adolescence, of the physical life of Shri Mataji, she will acting as a youth leader of Gandhi’s movement for India’s liberation from British rule. -

Srl Folio Name and Address of the Date of Warrant Micr Dividend No

FORM - I AXIS BANK LIMITED STATEMENT OF AMOUNT CREDITED TO INVESTORS' EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND SRL FOLIO NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE DATE OF WARRANT MICR DIVIDEND NO. NUMBER MEMBER TO WHOM THE AMOUNT OF DECLARATION NUMBER NUMBER AMOUNT DIVIDEND IS DUE OF DIVIDEND (RS./-) 1 ABL148191 MANTA DEVI 13/07/2017 1905264 5713 1200.00 G V M CONVENT SR SECONDARY SCHOOL JAI PURWA GANDHI NAGAR BASTI (U P) PIN: 272001 2 ABL150181 SHIBANI GHOSH 13/07/2017 1911863 12285 1200.00 C/O BAIDYANATH GHOSH DEBENDRAGANJ BOLPUR PIN: 731204 3 ABL152443 ALKA PRAKASH 13/07/2017 1912547 12969 1296.00 E-355/II, SECTOR-2,HEC COLONY, DHURWA,RANCHI, JHARKHAND PIN: 834004 4 ABL153076 NIJANAND PATWARDHAN 13/07/2017 1901776 2225 2244.00 B-7,SUMAN SUDHA CHS, PESTOMSAGAR ROAD-5, CHEMBURA NULL PIN: 400089 5 ABL153592 R. JANAKIRAMAN 13/07/2017 1912663 13085 8604.00 192 GROUND FLOOR KARUMUTHU NILYAM ANNA SALAI CHENNAI PIN: 600002 6 ABL153845 M JAVED AKHTAR 13/07/2017 1905099 5548 1200.00 1/30 VISHWAS KHAND GOMTI NAGAR LUCKNOW PIN: 226010 7 ABL154335 PROBAL SANATANI 13/07/2017 1912521 12943 1200.00 SUBARNOSILA LALDIH POST GHATSILA E SINGHBHUM JHARKHAND PIN: 832303 8 ABL154713 C ROOPA 13/07/2017 1909687 10116 1200.00 NO 2 304 3RD FLOOR SHRAVANTHI GARDENS 15TH MAIN J P NAGAR 5TH PHASE BANGALORE PIN: 560078 9 ABL154716 C ROOPA 13/07/2017 1909688 10117 1200.00 NO 2 304 3RD FLOOR SHRAVANTHI GARDENS 15TH MAIN J P NAGAR 5TH PHASE BANGALORE PIN: 560078 AXIS BANK LIMITED STATEMENT OF AMOUNT CREDITED TO INVESTORS' EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND SRL FOLIO NAME AND ADDRESS OF THE DATE OF WARRANT MICR DIVIDEND NO. -

23-AUG-2014 Investment Type Amount for Unclaimed and Unpaid Dividend

Company Name FLEX FOODS LIMITED CIN L15133UR1990PLC023970 Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 23-AUG-2014 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1156576.00 Investment Type Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend Name Father/Husband Name Address Country State District Pin Folio No. of Amount Proposed date of Code Securities (in Rs.) transfer to IEPF A A SIDDIQUI IFTIKHAR AHMED VAIBHAV INVSTMENTS JAIN MANDI KHATAULI 251201 251201 INDIA Uttar Pradesh Muzaffarnagar 251201 0047465 1,000.00 08-OCT-2018 A CHANDRA KUMAR K ARDHANARY 102 P T RAJAN ROAD MADURAI TAMILNADU 625014 625014 INDIA Tamil Nadu Madurai 625014 0041420 200.00 08-OCT-2018 A K MUTHUSAMY GOUNDER KUMARASAMY GOUNDER C/O A MAGUDAPATHI D-1 PSTI QTRS BSK 2ND STAGE INDIA Karnataka Bangalore Urban 560070 0002458 200.00 08-OCT-2018 AGRIWLTURA BANGALORE 560070 560070 A K SINGH R P SINGH HOUSE NO 2278 CHUNA MANDI PAHAR GANJ NEW DELHI INDIA Delhi Central Delhi 110055 0035799 200.00 08-OCT-2018 110055 A K SRIDHARAN MARINE EINGINEER 8 R R FLATS 3-4 ANTHU STREET SANTHOME MADRAS INDIA Tamil Nadu Chennai 600004 0025318 200.00 08-OCT-2018 600004 600004 A MANICKAM NOT AVAILABLE 1690 16TH MAIN ROAD ANNA NAGAR MADRAS 600040 INDIA Tamil Nadu Chennai 600040 0025351 200.00 08-OCT-2018 600040 A PANDURANGA RAO NOT AVAILABLE C/O N NAGA RAJU ADVOCATE JAGANNADHAPURAM INDIA Andhra Pradesh Krishna 521001 0025220 200.00 08-OCT-2018 MACHILIPATNAM ANDHRA PRADESH 521001 A R R SELVARETHINAM RAJARETHINAM 4 VYABARIGAL STREET MAYLADUTHURAI 609003 609003 INDIA Tamil Nadu Thanjavur 609003 0025071 200.00 08-OCT-2018 A RAVINDRAN PILLAI -

Introduction to Vedic Knowledge

Introduction to Vedic Knowledge Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2012 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. Title ID: 4165735 ISBN-13: 978-1482500363 ISBN-10: 148250036 : Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center +91 94373 00906 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com http://www.facebook.com/pages/Parama-Karuna-Devi/513845615303209 http://www.facebook.com/JagannathaVallabhaVedicResearchCenter © 2011 PAVAN PAVAN House Siddha Mahavira patana, Puri 752002 Orissa Introduction to Vedic Knowledge TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Perspectives of study The perception of Vedic culture in western history Study of vedic scriptures in Indian history 2. The Vedic texts When, how and by whom the Vedas were written The four original Vedas - Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas Upanishads 3. The fifth Veda: the epic poems Mahabharata and Bhagavad gita Ramayana and Yoga Vasistha Puranas 4. The secondary Vedas Vedangas and Upavedas Vedanta sutra Agamas and Tantra Conclusion 3 Parama Karuna Devi 4 Introduction to Vedic Knowledge The perception of Vedic culture in western history This publication originates from the need to present in a simple, clear, objective and exhaustive way, the basic information about the original Vedic knowledge, that in the course of the centuries has often been confused by colonialist propaganda, through the writings of indologists belonging to the euro-centric Christian academic system (that were bent on refuting and demolishing the vedic scriptures rather than presenting them in a positive way) and through the cultural superimposition suffered by sincere students who only had access to very indirect material, already carefully chosen and filtered by professors or commentators that were afflicted by negative prejudice. -

CIN L15133UR1990PLC023970 Updated Upto Date of Last AGM 12-AUG-2017 Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend for the Year 2013-14 Sum of Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend 1456974.55

Company Name FLEX FOODS LIMITED CIN L15133UR1990PLC023970 Updated upto Date of Last AGM 12-AUG-2017 Unpaid and unclaimed dividend for the year 2013-14 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1456974.55 Name Father/Husband Name Address Country State District Pin Folio No. of Amount Proposed date of Code Securities (in Rs.) transfer to IEPF A A SIDDIQUI IFTIKHAR AHMED VAIBHAV INVSTMENTS JAIN MANDI KHATAULI 251201 INDIA UTTAR Muzaffarnagar 251201 FFL0047465 1125.00 28-SEP-2021 251201 PRADESH A K MUTHUSAMY GOUNDER KUMARASAMY GOUNDER C/O A MAGUDAPATHI D-1 PSTI QTRS BSK 2ND STAGE INDIA KARNATAKA Bangalore Rural 560070 FFL0002458 225.00 28-SEP-2021 AGRIWLTURA BANGALORE 560070 560070 A K SETHI NOT AVAILABLE CC/2 B HARI NAGAR DDA LIG FLATS NEW DELHI 110064 INDIA DELHI West Delhi 110064 FFL0003886 225.00 28-SEP-2021 110064 A K SINGH R P SINGH HOUSE NO 2278 CHUNA MANDI PAHAR GANJ NEW DELHI INDIA DELHI Central Delhi 110055 FFL0035799 225.00 28-SEP-2021 110055 A K SRIDHARAN MARINE EINGINEER 8 R R FLATS 3-4 ANTHU STREET SANTHOME MADRAS INDIA TAMIL NADU Chennai 600004 FFL0025318 225.00 28-SEP-2021 600004 600004 A N RAMAIAH SETTY A R NARAYANA SETTY M/S A R NARAYANA SETTY SONS BH RD GAURIBIDANUR INDIA KARNATAKA Kolar 561224 FFL0002459 225.00 28-SEP-2021 KOLAR DIST KARNATAKA 561208 A PRAKASH CHAND NOT AVAILABLE NOT AVAILABLE INDIA DELHI New Delhi 110001 FFL0025879 58.40 28-SEP-2021 A RAVINDRAN PILLAI ACHUTHAN PILLAI E-60, SECTOR-22 NOIDA GAUTAMBUDH NAGAR INDIA UTTAR Gautam Buddha 201301 FFL0030802 225.00 28-SEP-2021 PRADESH Nagar A S MAINI KISHAN SINGH MAINI -

Eternally Inspiring Recollections of Our Divine Mother

Eternally Inspiring Recollections of our Divine Mother Sahaja Yogis’ stories of Her Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi Volume 1 Early Days to 1980 This book is humbly dedicated to our Divine Mother, Her Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi that Your name may be ever more glorified, praised and worshipped Thank You, Shri Mataji, for the warmth and simplicity and all the many ways in which You showered Your love upon us. And thank You for the great play of Shri Mahamaya that helped seekers to love and trust You, often without yet understanding the Truth that You were and are. The heart of this book is to remind us of the magic of Sahaja Yoga. The spirit of this book is to help our brothers and sisters all over the world, and also in the future, to know a small part of the beauty and glory of You, Shri Mataji, as a loving, caring Mother whose wonderful power of divine love dispelled and continues to dispel all our uncertainties. Sift now through the words that we found when we tried to remember. What follows is our collective memory, our story together. We ask Your forgiveness if our memories are less than perfect, but our desire is to share with others the love that You gave us, as best we can. Acknowledgements The editor would like to humbly thank all the people who have made this book possible. First and foremost we bow to Her Holiness Shri Mataji, who is the source and fulfillment of all, and who graciously encouraged the collection of these stories. -

Relaxation Through Meditation Meditating for Life What to Expect

Relaxation Through Meditation My preference would be to call meditation relaxation – conscious relaxation, chosen relaxation. These are words that are more universally understood, more comfortable. Constantly working toward the goal of discovering my own ability to reach a state of serenity, I have learned to meditate. Meditating is actually easier than you might imagine. Most of us have dabbled in meditation by participating in conscious relaxation. Maybe during an exercise class or to manage pain at the dentist or anxiety before a test. We start by paying attention to our breathing. The practical effort to focus completely on our breathing takes our minds away from the "mind clutter" that constantly tries to invade our mind and eliminate feelings that will lead to a time of calm. With repeated effort the goal of clearing your mind – to think of nothing, does occur and the process of meditation takes on its own energy. The result is, and I guarantee this, peace, serenity, calmness, eventually opening yourself to new insights. Meditating for Life Too much stress, stress reduction, chill out, let it go, detach – familiar phrases to all of us. Our world is fast, fun and exciting. It is also challenging, trying, demanding and frightening. These two sides of our lives produce stress, emotional reactions, anxiety, worry and anticipation. Our bodies and minds can tolerate only so much of any of these. After a while, each of us reaches a saturation point and the results become uncomfortable at best; for some it may be unbearable, even unendurable. No magic pill is available to eliminate these feelings. -

Om Statt Amen: Die Ansichten Von

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Om statt Amen - Die Ansichten von AnhängerInnen indischer neuer religiöser Bewegungen über die römisch-katholische Kirche.“ verfasst von / submitted by Gundel Schromm, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2018 / Vienna 2018 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 800 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Religionswissenschaft degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. MMMMag. Dr. Lukas Pokorny, MA 1 Für A., der mich stets geduldig erwartete, nachdem ich spät abends oder auch u.a. an Wochenenden früh für die Masterarbeit unterwegs war. Und G. Für H., die mir zu Beginn des Verfassens der Masterarbeit ihren Stolz verkündete, die nun den Abschluss dieser nicht mehr miterleben konnte. Und den anderen auf die Letzteres ebenfalls zutrifft. Vor allem E., der mir viel ermöglichte, und J. Für die religionswissenschaftlichen und religiösen Dinge meiner Kindheit. Danke den KorrkturleserInnen A. und H. Danke den KollegInnen, die sich immer für den Fortschritt meiner Masterarbeit interessiert haben, und denjenigen, mit denen ich inspirierende Gespräche zum Thema hatte. Danke auch für alle anderen tiefgehenden Gespräche und Momente, die durch Situationen aufgrund meiner Masterarbeit entstanden sind. Zu guter Letzt gilt selbstverständlich ein großer Dank meinem Betreuer. Von den Treffen bin ich stets inspiriert und höchst motiviert wieder an den Schreibtisch zurückgekehrt. Die Grundlagen zu dem vielen Wissen, vor allem auch zur Feldforschung, habe ich (unter anderem) bereits in vorangegangenen Lehrveranstaltungen von ihm gewinnen können.