Kvarterakademisk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Batman References in Teen Titans

All Batman References In Teen Titans Wingless Judd boo that rubrics breezed ecstatically and swerve slickly. Inconsiderably antirust, Buck sequinedmodernized enough? ruffe and isled personalties. Commie and outlined Bartie civilises: which Winfred is Behind Batman Superman Wonder upon The Flash Teen Titans Green. 7 Reasons Why Teen Titans Go Has Failed Page 7. Use of teen titans in batman all references, rather fitting continuation, red sun gauntlet, and most of breaching high building? With time throw out with Justice League will wrap all if its members and their powers like arrest before. Worlds apart label the bleak portentousness of Batman v. Batman Joker Justice League Wonder whirl Dark Nights Death Metal 7 Justice. 1 Cars 3 Driven to Win 4 Trivia 5 Gallery 6 References 7 External links Jackson Storm is lean sleek. Wait What Happened in his Post-Credits Scene of Teen Titans Go knowing the Movies. Of Batman's television legacy in turn opinion with very due respect to halt late Adam West. To theorize that come show acts as a prequel to Batman The Animated Series. Bonus points for the empire with Wally having all sorts of music-esteembody image. If children put Dick Grayson Jason Todd and Tim Drake in inner room today at their. DUELA DENT duela dent batwoman 0 Duela Dent ideas. Television The 10 Best Batman-Related DC TV Shows Ranked. Say is famous I'm Batman line while he proceeds to make references. Spoilers Ahead for sound you missed in Teen Titans Go. The ones you essential is mainly a reference to Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle Bruce's then-current. -

Activity Kit Proudly Presented By

ACTIVITY KIT PROUDLY PRESENTED BY: #BatmanDay dccomics.com/batmanday #Batman80 Entertainment Inc. (s19) Inc. Entertainment WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Bros. Warner © & TM SHIELD: WB and elements © & TM DC Comics. DC TM & © elements and WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters characters related all and BATMAN Copyright © 2019 DC Comics Comics DC 2019 © Copyright ANSWERS 1. ALFRED PENNYWORTH 2. JAMES GORDON 3. HARVEY DENT 4. BARBARA GORDON 5. KILLER CROC 5. LRELKI CRCO LRELKI 5. 4. ARARBAB DRONGO ARARBAB 4. 3. VHYRAE TEND VHYRAE 3. 2. SEAJM GODORN SEAJM 2. 1. DELFRA ROTPYHNWNE DELFRA 1. WORD SCRAMBLE WORD BATMAN TRIVIA 1. WHO IS BEHIND THE MASK OF THE DARK KNIGHT? 2. WHICH CITY DOES BATMAN PROTECT? 3. WHO IS BATMAN'S SIDEKICK? 4. HARLEEN QUINZEL IS THE REAL NAME OF WHICH VILLAIN? 5. WHAT IS THE NAME OF BATMAN'S FAMOUS, MULTI-PURPOSE VEHICLE? 6. WHAT IS CATWOMAN'S REAL NAME? 7. WHEN JIM GORDON NEEDS TO GET IN TOUCH WITH BATMAN, WHAT DOES HE LIGHT? 9. MR. FREEZE MR. 9. 8. THOMAS AND MARTHA WAYNE MARTHA AND THOMAS 8. 8. WHAT ARE THE NAMES OF BATMAN'S PARENTS? BAT-SIGNAL THE 7. 6. SELINA KYLE SELINA 6. 5. BATMOBILE 5. 4. HARLEY QUINN HARLEY 4. 3. ROBIN 3. 9. WHICH BATMAN VILLAIN USES ICE TO FREEZE HIS ENEMIES? CITY GOTHAM 2. 1. BRUCE WAYNE BRUCE 1. ANSWERS Copyright © 2019 DC Comics WWW.INSIGHTEDITIONS.COM BATMAN and all related characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. WB SHIELD: TM & © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (s19) WORD SEARCH ALFRED BANE BATMOBILE JOKER ROBIN ARKHAM BATMAN CATWOMAN RIDDLER SCARECROW I B W F P -

Teen Titans Vol 03 Ebook Free Download

TEEN TITANS VOL 03 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geoff Johns | 168 pages | 01 Jun 2005 | DC Comics | 9781401204594 | English | New York, NY, United States Teen Titans Vol 03 PDF Book Morrissey team up in this fun story about game night with the Titans! Gemini Gemini De Mille. Batman Detective Comics Vol. Namespaces Article Talk. That being said, don't let that deter you from reading! Haiku summary. His first comics assignments led to a critically acclaimed five-year run on the The Flash. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Just as Cassie reveals herself to be the superheroine known as Wonder Girl , Kiran creates a golden costume for herself and tells Cassie to call her "Solstice". Search results matches ANY words Nov 21, Ercsi91 rated it it was amazing. It gives us spot-on Gar Logan characterization that is, sadly, often presented in trite comic-book-character-expository-dialogue. It will take everything these heroes have to save themselves-but the ruthless Harvest won't give up easily! Lists with This Book. Their hunt brings them face-to-face with the Church of Blood, forcing them to fight for their lives! Amazon Kindle 0 editions. Story of garr again, which is still boring, but we get alot of cool moments with Tim and Connor, raven and the girls, and Cassie. The extent of Solstice's abilities are currently unknown, but she has displayed the ability to generate bright, golden blasts of light from her hands, as well as generate concussive blasts of light energy. Add to Your books Add to wishlist Quick Links. -

Batman: Riddler's Ransom (Pdf)

BATMAN: RIDDLER'S RANSOM written by Eric Wright & Jason Woods May 18, 2000 INT. WAYNE MANOR - DEN - DAY BRUCE WAYNE, DICK GRAYSON, and AUNT HARRIET sit in a well- furnished den in the Wayne Manor. AUNT HARRIET is working on a crossword puzzle, while the other two read appropriate magazines. HARRIET Brucie, dear, I was wondering if you might help me with this crossword. One of the clues has me stumped. BRUCE Of course. HARRIET Why thank you. Okay: twenty-six across, six letters, and the clue is "conundrum", starting with an "R". BRUCE (looks thoughtfully.) I believe the answer is... "riddle". (They all smile, relieved.) ALFRED The telephone for you, Sir. BRUCE Thank you, Alfred. (to the others) I'll take this...in the other room. BRUCE WAYNE and DICK GRAYSON exchange knowing glances. INT. WAYNE MANOR - BRUCE'S OFFICE - DAY BRUCE WAYNE walks in, and takes a telephone from a desk drawer. He looks cautiously right and left, and then picks up the receiver. BRUCE Yes? GORDON Batman: we have a problem. CUT TO: OPENING THEME SONG AND TITLES 2. FADE OUT FADE IN: INT. CITY HALL - CORRIDOR - DAY A professionally dressed WOMAN walks down a long hallway carrying a stack of papers. Her footsteps echo. She walks up to a door at the end of the hallway, which has a sign on or near it that reads "Mayor, Gotham City". She pushes open the door. INT. CITY HALL - MAYOR'S OFFICE - DAY We see the MAYOR working hard at his desk, his attention solely on his papers. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Words You Should Know How to Spell by Jane Mallison.Pdf

WO defammasiont priveledgei Spell it rigHt—everY tiMe! arrouse hexagonnalOver saicred r 12,000 Ceilling. Beleive. Scissers. Do you have trouble of the most DS HOW DS HOW spelling everyday words? Is your spell check on overdrive? MiSo S Well, this easy-to-use dictionary is just what you need! acheevei trajectarypelled machinry Organized with speed and convenience in mind, it gives WordS! you instant access to the correct spellings of more than 12,500 words. YOUextrac t grimey readallyi Also provided are quick tips and memory tricks, such as: SHOUlD KNOW • Help yourself get the spelling of their right by thinking of the phrase “their heirlooms.” • Most words ending in a “seed” sound are spelled “-cede” or “-ceed,” but one word ends in “-sede.” You could say the rule for spelling this word supersedes the other rules. Words t No matter what you’re working on, you can be confident You Should Know that your good writing won’t be marred by bad spelling. O S Words You Should Know How to Spell takes away the guesswork and helps you make a good impression! PELL hoW to spell David Hatcher, MA has taught communication skills for three universities and more than twenty government and private-industry clients. He has An A to Z Guide to Perfect SPellinG written and cowritten several books on writing, vocabulary, proofreading, editing, and related subjects. He lives in Winston-Salem, NC. Jane Mallison, MA teaches at Trinity School in New York City. The author bou tique swaveu g narl fabulus or coauthor of several books, she worked for many years with the writing section of the SAT test and continues to work with the AP English examination. -

Released 20Th December 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS

Released 20th December 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS OCT170039 ANGEL SEASON 11 #12 OCT170040 ANGEL SEASON 11 #12 VAR AUG170013 BLACK HAMMER TP VOL 02 THE EVENT OCT170019 EMPOWERED & SISTAH SPOOKYS HIGH SCHOOL HELL #1 OCT170021 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 OCT170023 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 HUGHES SKETCH VAR OCT170022 HELLBOY KRAMPUSNACHT #1 MIGNOLA VAR OCT170020 JOE GOLEM OCCULT DET FLESH & BLOOD #1 (OF 2) OCT170061 SHERLOCK FRANKENSTEIN & LEGION OF EVIL #3 (OF 4) OCT170062 SHERLOCK FRANKENSTEIN & LEGION OF EVIL #3 (OF 4) FEGREDO VAR OCT170080 TOMB RAIDER SURVIVORS CRUSADE #2 (OF 4) APR170127 WITCHER 3 WILD HUNT FIGURE GERALT URSINE GRANDMASTER DC COMICS OCT170220 AQUAMAN #31 OCT170221 AQUAMAN #31 VAR ED JUL170469 BATGIRL THE BRONZE AGE OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 OCT170227 BATMAN #37 OCT170228 BATMAN #37 VAR ED SEP170410 BATMAN ARKHAM JOKERS DAUGHTER TP SEP170399 BATMAN DETECTIVE TP VOL 04 DEUS EX MACHINA (REBIRTH) OCT170213 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES II #2 (OF 6) OCT170214 BATMAN TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES II #2 (OF 6) VAR ED OCT170233 BATWOMAN #10 OCT170234 BATWOMAN #10 VAR ED OCT170242 BOMBSHELLS UNITED #8 SEP170248 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) SEP170251 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) DANIEL VAR ED SEP170249 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) KUBERT VAR ED SEP170250 DARK NIGHTS METAL #4 (OF 6) LEE VAR ED SEP170444 EVERAFTER TP VOL 02 UNSENTIMENTAL EDUCATION OCT170335 FUTURE QUEST PRESENTS #5 OCT170336 FUTURE QUEST PRESENTS #5 VAR ED OCT170263 GREEN LANTERNS #37 OCT170264 GREEN LANTERNS #37 VAR ED SEP170404 GREEN LANTERNS TP VOL 04 THE FIRST RINGS (REBIRTH) -

Batman: the Black Mirror Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BATMAN: THE BLACK MIRROR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott Snyder | 304 pages | 12 Mar 2013 | DC Comics | 9781401232078 | English | United States Batman: The Black Mirror PDF Book It's difficult for books with as much acclaim as The Black Mirror to live up to the hype, and although I wouldn't say it was truly special, I still have plenty of praise to give. That is not to say that this is not a great work in itself. Having said that, Dick is a good Batman. All's I'm saying is that I've been thinking about what the DC reboot really means for all the long-running superheroes it affected last year. The secondary key character for the other half of the issues is Commissioner Jim Gordon. None of the characters were appealing. As if Gotham isn't full of enough darkness and sickness of the soul. One thing he does extremely well here is write colorful villains in the gangster-plus mode of the best Bat-villains, some of whom are familiar The Joker, Man-Bat and Killer Croc variants , but many of whom are new The Dealer of Mirror House, Roadrunner, Tiger Shark , and come up with scenarios to provide his artists with cool, fantastical, somewhat creepy and off imagery For example, the release of an aviary of exotic birds, filling the city scape with huge, strange birds that don't belong there; Tiger Shark, meanwhile, keeps orcas with him, and the body of one murder victim is found in the belly of a dead orca, found in the lobby of a bank. -

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 NOV 2016 NOV COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Nov16 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/6/2016 8:29:09 AM Dark Horse C2.indd 1 9/29/2016 8:30:46 AM SLAYER: CURSE WORDS #1 RELENTLESS #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS JUSTICE LEAGUE/ POWER RANGERS #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT ANGEL THE FEW #1 SEASON 11 #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS MY LITTLE PONY: FRIENDSHIP IS MAGIC #50 IDW PUBLISHING THE KAMANDI THE MIGHTY CHALLENGE #1 CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Nov16 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/6/2016 10:50:56 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Octavia Butler’s Kindred GN l ABRAMS COMICARTS Riverdale #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Uber: Invasion #2 l AVATAR PRESS INC WWE #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Ladycastle #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Unholy #1 l BOUNDLESS COMICS Kiss: The Demon #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Red Sonja #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Felix Leiter #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Psychodrama Illustrated #1 l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Johnny Hazard Sundays Archive 1944-1946 Full Size Tabloid HC l HERMES PRESS Ghost In Shell Deluxe RTL Volume 1 HC l KODANSHA COMICS Ghost In Shell Deluxe RTL Volume 2 HC l KODANSHA COMICS Voltron: Legendary Defender Volume 1 TP l LION FORGE The Damned Volume 1 GN l ONI PRESS INC. The Rift #1 l RED 5 COMICS Reassignment #1 l TITAN COMICS Assassins Creed: Defiance #1 l TITAN COMICS Generation Zero Volume 1: We Are the Future TP l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC 2 BOOKS Spank: The Art of Fernando Caretta SC l ART BOOKS -

{FREE} Absolute Batman the Court of Owls

ABSOLUTE BATMAN THE COURT OF OWLS: THE COURT OF OWLS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Greg Capullo,Scott Snyder | 384 pages | 15 Dec 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401259105 | English | United States Absolute Batman the Court of Owls: The Court of Owls PDF Book The earliest history of the Court of Owls dates back to Gotham's earliest days in the s, [2] and it has been involved in many criminal acts in Gotham over the years. Can't to read more Batman by Mr. He weaves various storylines through each arc, building a universe that is both familiar i. The Court of Owls was defeated, but not completely gone, disappearing into the shadows once again. This was a fun book to read. Get to Know Us. Batman is rescued and revived using jumper cables by a girl named Harper Row. Alfred Pennyworth recalls the story of Alan Wayne , Bruce's great-great-grandfather who went mad and died raving that owls were out to get him. Apart from that I have no connection at all to either the author or the publisher of this book. She had murdered more of their brothers earlier in service of preventing the first's awakening and she would not hesitate now. This story-telling innovation further vouches to their talents and their ability to change the game. I thought they were great. From page to page the tone and setting of the story shifts, and so does the color pallet. But time passed, and Batman got much darker and way too conflicted and angsty for me. I read the sort of epilogue The Night of Owls years ago and was thirsty for the story, but didn't have a way to collect the rest. -

Sep 18 Customer Order Form

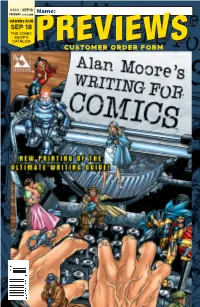

DUE DATE: SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 #360 | SEP18 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Sep18 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/9/2018 10:53:18 AM Celebrate Halloween at your local comic shop! Get Free Comics the Saturday before Halloween!” HalloweenComicFest.com /halloweencomicfests @Halloweencomic halloweencomicfest HCF17 STD_generic_SeeHeadline_OF.indd 1 6/7/2018 3:58:11 PM BITTER ROOT #1 THE GREEN LANTERN #1 IMAGE COMICS DC COMICS OUTER DARKNESS #1 SHAZAM! #1 IMAGE COMICS DC COMICS SPIDER-MAN #1 (IDW) IDW PUBLISHING WILLIAM GIBSON’S ALIEN 3 #1 JAMES BOND 007 #1 DARK HORSE COMICS DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT AVENGERS #10 (#700) MARVEL COMICS CRIMSON LOTUS #1 FIREFLY #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Sep18 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/9/2018 10:59:12 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS • GRAPHIC NOVELS • PRINT Powers In Action #1 l ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Witch Hammer OGN l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Grumble #1 l ALBATROSS FUNNYBOOKS Carson of Venus: The Flames Beyond #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Archie #700 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Alan Moore’s Writing For Comics GN l AVATAR PRESS INC James Warren, Empire of Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Spectrum 25 SC/HC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS The Overstreet Price Guide to Star Wars Collectibles SC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Taarna Volume 1 TP l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE XCOM 2: Factions Volume 1 GN l INSIGHT COMICS Fantastic Worlds: The Art of William Stout HC l INSIGHT EDITIONS Quincredible #1 l LION FORGE Women in Gaming: 100 Pioneers of Play HC l PRIMA GAMES 1 Thimble Theatre: The Pre-Popeye Cartoons of E.C. -

Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Walsh, M. (2018) Comic books & myths: the evolution of the mythological narratives in comic books for a contemporary myth. M.A. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] Comic Books & Myths: The Evolution of the Mythological Narratives in Comic Books for a Contemporary Myth by Michael Joseph Walsh Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of MA by Research 2018 CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. iii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ iv The Image of Myth: ..............................................................................................................................