North Bay, Mattawa, and West Nipissing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consolidated Municipal Services Managers and Areas Served

CONSOLIDATED MUNICIPAL SERVICES MANAGERS AND AREAS SERVED Consolidated Municipal Services Managers (CMSMs) in Southern Ontario provide a similar range of programs and services and also provide land ambulance and public health services with the approval of the Minister of Health. The role of the delivery agent in the provision of social services has progressed over time. The Local Services Realignment announced by the government in January 1997, outlined new directions for the delivery of social assistance, child care and social housing. These changes have created the opportunity to implement a more integrated system of social and community health services under municipal leadership. An integrated system is one in which policies; programs and services are coordinated and complementary and serve common goals that address the well being of individuals, families and communities. Consolidation of municipal service management has resulted in the management of the delivery of social assistance, child care, and social housing by 36 municipalities in Southern Ontario and by 10 District Social Services Administration Boards as well as the Regional Municipality of Sudbury in Northern Ontario. Authority to require consolidation of municipal service management is provided by the Services Improvement Act and the Social Assistance Reform Act. In Northern Ontario, ten District Social Services Administration Boards (DSSABs) and the Regional Municipality of Sudbury were approved as CMSMs. DSSABs are responsible for serving both municipalities and territories without municipal organization. The nine southern Ontario regional municipalities plus the City of Toronto are, by legislation, boards of health for their region, as well as CMSMs. [Please refer to attached chart outlining Consolidated Municipal Service Managers - Ontario Works, Child Care and Social Housing -- area served in Southern and Northern Ontario] 1 Consolidated Municipal Service Managers Ontario Works, Child Care and Social Housing Service Manager Area Served SOUTHERN ONTARIO 1. -

Nipissing District Contact Colours School Persons Team Name Classification

2016-2017 N.O.S.S.A. - MEMBER SCHOOLS' DIRECTORY Page 1 NIPISSING DISTRICT CONTACT COLOURS SCHOOL PERSONS TEAM NAME CLASSIFICATION 1. E.S.C. Algonquin (NOAL) Tim Lowe Maroon/White 555 Algonquin Avenue Pat Lalonde Barons North Bay, Ontario P1B 4W8 "A" Ph. 472 8240 FAX 472-8476 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 2. E.S. Franco-Cite (NOFC) Rock Lachance Orange/Black/ 90 Rue Main Brigitte Marleau White Sturgeon Falls, Ontario P2B 2Z7 Patriotes Ph. 753-1510 FAX 753-5370 “A” Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3. Chippewa Secondary School (NOCW) Dez Forget Scarlet/Gold 539 Chippewa St. W. Raiders North Bay, Ontario P1B 6G8 "AA" Ph. 475-2341 ext 5 FAX 476-0845 Email: [email protected] 4. E.S.C. Élisabeth-Bruyère (NOEB) Kareena Lindsay Purple/Grey/Black 359, rue Brydges, C.P. 1010 Loups Mattawa, Ontario. P0H 1V0 "A"/”B” Ph. 744-5505 Email: [email protected] 5. F.J. McElligott (NOME) Scot Quarrington Blue/Gold 370 Pine Street Voyageurs Mattawa, Ontario. P0H 1V0 "A"/”B” Ph. 472-5720 FAX 744-0786 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 6. E.S. Northern SS (NONO) Daniel Stevens Silver/Red 175 Ethel Street Braves Sturgeon Falls, Ontario P2B 2Z8 "A" Ph. 472-5322 FAX 753-2400 Email: [email protected] Northern Ontario Secondary School Athletics (N.O.S.S.A.) 2016-2017 N.O.S.S.A. - MEMBER SCHOOLS' DIRECTORY Page 2 NIPISSING DISTRICT (cont’d) CONTACT COLOURS SCHOOL PERSONS TEAM NAME CLASSIFICATION 7. -

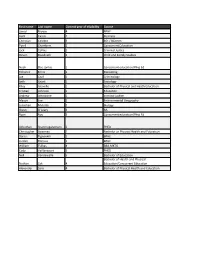

First Name Last Name Current Year of Eligibility Course Jamal Brown 4

First name Last name Current year of eligibility Course Jamal Brown 4 BPHE Liam Cassis 1 Business Christian Celebre 3 BSc / BComm Tyrell Chambers 2 Concurrent Education Jack Collins 2 Criminal Justice Deven Doodnath 2 Child and Family Studies Noah Dos santos 1 Concurrent education/Phys Ed Yohance Ennis 2 Marketing Joe Graf 1 Criminology Seth Grant 1 Sociology Riley Gravelle 1 Bachelor of Physical and Heath Education Kristian Johnson 1 Education Andrew Johnstone 1 criminal justice Mason Lee 2 Environmental Geography Jonathan Mulimbi 2 Biology Owen O'Leary 3 BA Ryan Roy 3 Concurrent education/Phys Ed Achuthan Shanmugaratnam 2 PHED Christopher Sweeney 2 Bachelor or Physical Health and Education Darius Tignanelli 1 BPHE Jordan Titmuss 1 BPHE William Tsilkas 4 BBA.MKTG Cody Vaillancourt 3 PHED Neil Vandewalle 5 Bachelor of Education Bachelor of Health and Physical Nathan Zak 4 Education/Concurrent Education Alexander Zero 4 Bachelor of Physical Health and Education Year of study Home town Home province Last team 4 Barrie ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) 1 North Bay ON Fiorentina FC OCSL 3 North Bay ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) 3 Brampton ON CAF League 2 Ottawa ON OSU 3 Toronto ON Toronto Skillz FC, League1 Ontario Parkside soccer (tvdsb), Parkside volleyball (tvdsb), Parkside hockey (tvdsb), Croatia men's 1 St Thomas ON premier 2 toronto ON Toronto Skillz fc League One 1 North Bay ON St Anthony’s Soccer Club 1 North Bay ON Ottawa South United, League 1 Ontario 2 North Bay ON Widdifield S.S. 1 North Bay ON Carleton Place Soccer Club, ERSL 3 Barrie ON algoma University 2 Innisfil ON Bradford Wolves FC 3 Ottawa ON Nationwide School For Academic Excellence 4 Mitchell ON FC London & League 1 3 Barrie ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) Pope John Paul II Catholic Secondary School: 2 Scarborough ON Men's Soccer, Ultimate Frisbee, Swimming 2 North Bay ON David FC, North Bay Men's League 4 NORTH BAY ON Nipissing District Mens Soccer 1 NORTH BAY ON fogo fc soccer 4 Richmond Hill ON markham lightning 3 North Bay ON Nipissing Lakers (OUA) 6 St. -

Rank of Pops

Table 1.3 Basic Pop Trends County by County Census 2001 - place names pop_1996 pop_2001 % diff rank order absolute 1996-01 Sorted by absolute pop growth on growth pop growth - Canada 28,846,761 30,007,094 1,160,333 4.0 - Ontario 10,753,573 11,410,046 656,473 6.1 - York Regional Municipality 1 592,445 729,254 136,809 23.1 - Peel Regional Municipality 2 852,526 988,948 136,422 16.0 - Toronto Division 3 2,385,421 2,481,494 96,073 4.0 - Ottawa Division 4 721,136 774,072 52,936 7.3 - Durham Regional Municipality 5 458,616 506,901 48,285 10.5 - Simcoe County 6 329,865 377,050 47,185 14.3 - Halton Regional Municipality 7 339,875 375,229 35,354 10.4 - Waterloo Regional Municipality 8 405,435 438,515 33,080 8.2 - Essex County 9 350,329 374,975 24,646 7.0 - Hamilton Division 10 467,799 490,268 22,469 4.8 - Wellington County 11 171,406 187,313 15,907 9.3 - Middlesex County 12 389,616 403,185 13,569 3.5 - Niagara Regional Municipality 13 403,504 410,574 7,070 1.8 - Dufferin County 14 45,657 51,013 5,356 11.7 - Brant County 15 114,564 118,485 3,921 3.4 - Northumberland County 16 74,437 77,497 3,060 4.1 - Lanark County 17 59,845 62,495 2,650 4.4 - Muskoka District Municipality 18 50,463 53,106 2,643 5.2 - Prescott and Russell United Counties 19 74,013 76,446 2,433 3.3 - Peterborough County 20 123,448 125,856 2,408 2.0 - Elgin County 21 79,159 81,553 2,394 3.0 - Frontenac County 22 136,365 138,606 2,241 1.6 - Oxford County 23 97,142 99,270 2,128 2.2 - Haldimand-Norfolk Regional Municipality 24 102,575 104,670 2,095 2.0 - Perth County 25 72,106 73,675 -

Looking for a Boiler Supply & Servicing Company with The

Service Area Volume 49 • June 2017 South West tel: 519 884 0600 505 Dotzert Court, fax: 519 884 0213 Unit 1 toll free: 1 800 265 8809 Waterloo, ON N2L 6A7 www.waterloomanufacturing.ca East tel: 613 228 3597 19 Grenfell Crescent, Bay 1 fax: 613 225 0116 Ottawa (Nepean) ON toll free: 1 800 265 8809 K2G 0G3 www.waterloomanufacturing.ca Looking For A Boiler Supply & Servicing Company With The Knowledge & Experience To Get It Right? We are that company and we want to help you optimize your boiler room. Established in 1850, Waterloo Manufacturing Ltd. has a long history of growth and evolution that continues to this day. In our early days we began as a manufacturer of farm machinery equipment, steam engines, pulp and paper rolls, and in 1947, became an authorized Cleaver Brooks Representative for South West Ontario. In 1984, we streamlined the company to further focus on solely providing boiler room equipment solutions in South West Ontario. In 2015, a unique opportunity arose to expand our company to include the Eastern Ontario region formerly covered by John M. Schermerhorn Ltd. In 2017, a further opportunity arose to expand our company to include the territory formerly represented by Johnson Paterson, Inc. to be the sole representative for Cleaver Brooks in the province of Ontario. *Refer to Map on Page 4. Ontario West Central Ontario Ontario East • Brant County • Algoma District • Carleton County • Bruce County • Cochrane District • Dundas County • Dufferin County • Durham County • Frontenac County • Elgin County • Haliburton County • Glengarry -

Community Profiles for the Oneca Education And

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 Political/Territorial Facts About This Community Phone Number First Nation and Address Nation and Region Organization or and Fax Number Affiliation (if any) • Census data from 2006 states Aamjiwnaang First that there are 706 residents. Nation • This is a Chippewa (Ojibwe) community located on the (Sarnia) (519) 336‐8410 Anishinabek Nation shores of the St. Clair River near SFNS Sarnia, Ontario. 978 Tashmoo Avenue (Fax) 336‐0382 • There are 253 private dwellings in this community. SARNIA, Ontario (Southwest Region) • The land base is 12.57 square kilometres. N7T 7H5 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 506 residents. Alderville First Nation • This community is located in South‐Central Ontario. It is 11696 Second Line (905) 352‐2011 Anishinabek Nation intersected by County Road 45, and is located on the south side P.O. Box 46 (Fax) 352‐3242 Ogemawahj of Rice Lake and is 30km north of Cobourg. ROSENEATH, Ontario (Southeast Region) • There are 237 private dwellings in this community. K0K 2X0 • The land base is 12.52 square kilometres. COPYRIGHT OF THE ONECA EDUCATION PARTNERSHIPS PROGRAM 1 FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES 2010 • Census data from 2006 states that there are 406 residents. • This Algonquin community Algonquins of called Pikwàkanagàn is situated Pikwakanagan First on the beautiful shores of the Nation (613) 625‐2800 Bonnechere River and Golden Anishinabek Nation Lake. It is located off of Highway P.O. Box 100 (Fax) 625‐1149 N/A 60 and is 1 1/2 hours west of Ottawa and 1 1/2 hours south of GOLDEN LAKE, Ontario Algonquin Park. -

Nipissing District Contact Colours School Persons Team Name Classification

2014-2015 N.O.S.S.A. - MEMBER SCHOOLS' DIRECTORY Page 1 NIPISSING DISTRICT CONTACT COLOURS SCHOOL PERSONS TEAM NAME CLASSIFICATION 1. E.S.C. Algonquin (NOAL) Lisa Hotte Maroon/White 555 Algonquin Avenue Barons North Bay, Ontario P1B 4W8 "A" Ph. 472 8240 FAX 472-8476 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 2. E.S. Franco-Cite (NOFC) Rock Lachance Orange/Black/ 90 Rue Main Brigitte Marleau White Sturgeon Falls, Ontario P2B 2Z7 Patriotes Ph. 753-1510 FAX 753-5370 “A” Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3. Chippewa Secondary School (NOCW) Dez Forget Scarlet/Gold 539 Chippewa St. W. Raiders North Bay, Ontario P1B 6G8 "A" Ph. 472-4010 ext 226 FAX 476-0845 Email: [email protected] 4. E.S.C. Élisabeth-Bruyère (NOEB) Sue Martel Purple/Grey/Black 359, rue Brydges, C.P. 1010 Loups Mattawa, Ontario. P0H 1V0 "A"/”B” Ph. 744-5505 Email: [email protected] 5. F.J. McElligott (NOME) Scott Quarrington Blue/Gold 370 Pine Street Voyageurs Mattawa, Ontario. P0H 1V0 "A"/”B” Ph. 472-5720 FAX 744-0786 Email: [email protected] 6. E.S. Northern SS (NONO) Richard Lachance Silver/Red 175 Ethel Street Daniel Stevens Braves Sturgeon Falls, Ontario P2B 2Z8 "A" Ph. 472-5322 FAX 753-2400 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Northern Ontario Secondary School Athletics (N.O.S.S.A.) 2014-2015 N.O.S.S.A. - MEMBER SCHOOLS' DIRECTORY Page 2 NIPISSING DISTRICT (cont’d) CONTACT COLOURS SCHOOL PERSONS TEAM NAME CLASSIFICATION 7. -

Invading Species Awareness Program for Ontario 2009

2009/10 Invading Species Awareness Program for Ontario Annual Report for 2009/10 INVADING SPECIES AWARENESS PROGRAM EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Invading Species Awareness Program The Invading Species Awareness Program (ISAP) has been a joint partnership initiative of the O.F.A.H. and the MNR since 1992; focusing on preventing invasive species introductions to Ontario’s forests and waters. In 2009, in collaboration with hundreds of community groups, nongovernment organizations and all levels of government, the ISAP reached hundreds of thousands of Ontarians engaging their participation in prevention. Hundreds of citizen scientists and professional field staff from numerous agencies participated in our monitoring and reporting programs. The ISAP made valuable contributions to early detection and rapid response initiatives for invasive species threatening Ontario’s biodiversity such as Asian carp, kudzu, European water chestnut, and water soldier. 2009 marked the successful completion of a multi‐year provincial effort to train the bait industry to implement aquatic invasive species prevention plans throughout their industry. The ISAP made significant contributions to provincial, national and international initiatives including the Ontario Invasive Plant Council, the U.S. Great Lakes Panel on Aquatic Nuisance Species and the Canadian Aquatic Invasive Species Network, and the development of the bi‐national Lake Superior Aquatic Invasive Species Prevention Plan. Partnerships In 2009, the O.F.A.H. and the MNR continued the successful joint delivery of the ISAP, with O.F.A.H. staff working collaboratively with staff from MNR’s Biodiversity Section, as well as numerous district offices around the province. Federally, funding contributions were made from Environment Canada’s Invasive Alien Species Partnership Program, and the Lake Simcoe Clean Up Fund, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Human Resources Development Canada’s Canada Summer Jobs Program and Eco‐Canada. -

Nipissing District Developmental Screen (NDDS)

Early Childhood Measurement and Evaluation Tool Review Early Childhood Measurement and Evaluation (ECME), a portfolio within CUP, produces Early Childhood Measurement Tool Reviews as a resource for those who conduct screening, assessment, and evaluation. To learn more about ECME and CUP, provide feedback, or to access additional reviews, visit our website at www.cup.ualberta.ca or email us at [email protected] Nipissing District Developmental Screen (NDDS) Measurement Areas: The NDDS is a developmental screen, which is a short checklist of some of the most critical skills that a child should master by a particular age. It is a quick survey to determine any areas that may require some extra help. The questionnaire addresses the following developmental areas: Vision • Hearing In the child’s first language • Communication (Speech and Language) • Gross motor • Fine motor • Cognitive • Social-emotional • Self-help skills • The NDDS screens coincide with immunization schedules and provide parents with reminders of key developmental stages. There are 13 age specific forms of the NDDS ranging from 1 month to six years. The forms are specific to 1 & 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months, 15 months, 18 months, 2 years, 30 months, 3 years, 4 years, 5 years and 6 years. Purpose: The NDDS was designed to provide a user-friendly method for documenting the development and progress of infants and children. The NDDS provides a general overview of the child’s development the day the screening takes place. According to author report, the NDDS allows parents to: • Learn about their child’s development • Recognize their child’s skills and abilities • Identify developmental areas that may need extra attention The NDDS is designed to be completed by parents or health / childcare professionals S04 1 of 4 Length and Structure: On the13 age specific forms of the NDDS the number of items, on each questionnaire, ranges from 4 to 22. -

Clinics Adult Diabetes Education Centre

Assistive Devices Program, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Clinics Adult Diabetes Education Centre City Name Address Postal Telephone Code Barrie Barrie And Community 200 - 125 Bell Farm Road L4M 6L2 705-797-2030 Family Health Team Diabetes Education Centre Barrie LMC Endocrinology 306 - 5 Quarry Ridge Road L4M 7G1 705-737-0830 Centres Barrie Simcoe Diabetes 206 - 128 Penetang St L4M 1V6 705-734-3888 Education Centre Adult Diabetes Care Centre Belleville Belleville Nurse 231 Front St K8N 2Z4 613-779-7304 Practitioner Led Clinic x 210 Bracebridge Bracebridge Diabetes 205 Hiram St P1L 2C1 705-645-8824 Centre Brampton William Osler Health 2100 Bovaird Drive East, L6R 3J7 905-494-2120 Centre Diabetes Education S.3.720 x 56627 Centre Brampton LMC Endocrinology 238 - 2130 North Park Drive L6S 0C9 905-595-0560 Centres Brantford Brantford General Hospital 200 Terrace Hill St N3R 1G9 519-751-5544 Diabetes Education Centre x 4955 Burlington Dr. Jeffery D. Lang 302 - 3155 Harvester Road L7N 3V2 905-634-0800 Burlington JBN Medical Diagnostics 301 - 2951 Walkers Line L7M 4Y1 905-331-3960 Diabetes Education Centre Cambridge Cambridge Memorial 700 Coronation Blvd N1R 3G2 519-621-2333 Hospital Diabetes x 2345 Education Centre Chatham Chatham-Kent Health 80 Grand Avenue West N7M 5L9 519-352-6401 Alliance Diabetes P.O. BOX 2030 x 6086 Education Centre City Name Address Postal Telephone Code Collingwood Georgian Bay Family 100 - 186 Erie St L9Y 4T3 705-444-5885 Health Team Cornwall Cornwall Community 510 Second St East K6H 1Z6 613-932-3300 Hospital Diabetes 2nd Floor x 2031 Education Centre Deep River Deep River And District 117 Banting Drive K0J 1P0 613-584-3333 Hospital Diabetes x 313 Education Centre Etobicoke William Osler Health 224 - 89 Humber College M9V 4B8 416-747-3400 Centre Etobicoke Diabetes Blvd. -

District of Parry Sound Demographic Profile

District of Parry Sound Demographic Profile 2011 Census of Population Developed in partnership with District of Parry Sound Community Development Collaborative April, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ..................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 5 REPORT PURPOSE ....................................................................................................................................... 5 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................................................... 6 REPORT PRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 6 NOTES ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 KEY FINDINGS.............................................................................................................................................. 8 Population............................................................................................................................................... 8 Age and Sex............................................................................................................................................ -

Paramedic Board Presentation

MANDATE • The Board has been tasked under the Ambulance Act to insure provision of Land Ambulance to all citizens in the district of Nipissing and cost share 50/50 for the total cost of ambulance services. • The Board is the Designated Delivery Agent for the District of Nipissing. OPERATION OPTIONS (2001) 1. Same Provider 2. Direct Delivery - Remain with the same provider at - Paramedic 3. Third Party the download in employees of 2001 DNSSAB - Certified - 80 plus Ambulance paramedics Provider (RFP) - Present Model NIPISSING AMBULANCE (PARAMEDIC) SERVICES PROVIDERS North Bay Mattawa Regional General Town of Health Centre Hospital Temagami North Bay Mattawa Temagami West Calvin Nipissing Papineau- Chisholm Cameron South Mattawan Algonquin Bonfield East Ferris NIPISSING DISTRICT COMMUNITIES NIPISSING AMBULANCE ( PARAMEDIC) SERVICES PROVIDERS • All providers must be certified and inspected by MOH & Long Term Care at a minimum every 3 year • Providers are fully responsible to insure that all aspect of the act are followed • The paramedics are employees of the provider and not the DNSSAB all HR issues are dealt by the provider (Employment Standards, Collective agreements Health & Safety and any other act that may apply) NIPISSING AMBULANCE (PARAMEDIC) SERVICE PROVIDERS • The DNSSAB manages the funding distribution to meet the need of the districts citizens in pre-hospital primary emergency care • The DNSSAB purchases medical equipment to stock ambulances • The DNSSAB purchases paramedics uniforms • The DNSSAB processes monthly Electronic Fund