Profile of Internal Displacement : Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galilee, Galileans I. Geography

907 Galilee, Galileans 908 potential for anti-Sacramentarian polemic (Comm. Galilee (mAr 9 : 2). Not only do we have here a divi- Gen. 31.48-55). sion between Upper and Lower Galilee, but the mention of the sycamore tree (Shiqma) reflects the Bibliography : ■ Calvin, J., Commentaries on the First Book of Moses Called Genesis, vol. 2 (trans. J. King; Grand Rapids, differences in altitude and vegetation between Up- Mich. 1989). ■ Luther, M., Luther’s Works, vol. 6 (ed. J. J. per Galilee (1200 m. above sea level) and Lower Gal- Pelikan, Saint Louis, Miss. 1970). ■ Sheridan, M. (ed.), Gen- ilee (600 m. above sea level), as sycamores do not esis 12–50 (Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, vol. grow in areas higher than 400 m. above sea level. 2; Downers Grove, Ill., 2002). ■ Skinner, J., A Critical and The term “Galileans” appears only in the late Exegetical Commentary on Genesis (ICC; Edinburgh 1930). Second Temple period. This is a good reason to con- ■ Speiser, E. A., Genesis (AB 1; New York/London 1964). nect it to the self-identification of the Jews living in John Lewis this region or the Judeans identifying the Galileans. See also /Mizpah, Mizpeh To understand this self-identity it is necessary to present the development of the Jewish settlement in the Galilee from the First Temple period to the Galilee, Galileans 1st century CE. It is very clear today, according to I. Geography many archaeological excavations which were con- II. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament ducted in the Galilee that its Israelite population III. New Testament collapsed after the Assyrian attack in 732 BCE. -

Focuspoint International 866-340-8569 861 SW 78Th Avenue, Suite B200 [email protected] Plantation, FL 33324 SUMMARY NN02

INFOCUS QUARTERLY SUMMARY TERRORISM & CONFLICT, NATURAL DISASTERS AND CIVIL UNREST Q2 2021 FocusPoint International 866-340-8569 861 SW 78th Avenue, Suite B200 [email protected] Plantation, FL 33324 www.focuspointintl.com SUMMARY NN02 NATURAL DISASTERS Any event or force of nature that has cyclone, hurricane, tornado, tsunami, volcanic catastrophic consequences and causes eruption, or other similar natural events that give damage or the potential to cause a crisis to a rise to a crisis if noted and agreed by CAP customer. This includes an avalanche, FocusPoint. landslide, earth quake, flood, forest or bush fire, NUMBER OF INCIDENTS 32 3 3 118 20 9 Asia Pacific 118 Sub-Saharan Africa 20 Middle East and North Africa 3 Europe 32 Domestic United States and Canada 3 Latin America 9 MOST "SIGNIFICANT" EVENTS • Indonesia: Tropical Cyclone Seroja • Canada: Deaths in connection with • DRC: Mt. Nyiragongo eruption an ongoing heatwave • Algeria: Flash Floods • Panama: Floods/Landslides • Russia: Crimea and Krasnodar Krai flooding 03 TERRORISM / CONFLICT Terrorism means an act, including but not government(s), committed for political, limited to the use of force or violence and/or the religious, ideological or similar purposes threat thereof, of any person or group(s) of including the intention to influence any persons, whether acting alone or on behalf of or government and/or to put the public, or any in connection with any organization(s) or section of the public, in fear. NUMBER OF INCIDENTS 20 1 270 209 144 15 Asia Pacific 209 Sub-Saharan Africa 144 Middle East and North Africa 270 Europe 20 Domestic United States and Canada 1 Latin America 15 MOST "SIGNIFICANT" EVENTS • Taliban Attack on Ghazni • Tigray Market Airstrike • Solhan Massacre • Landmine Explosion 04 POLITICAL THREAT / CIVIL UNREST The threat of action designed to influence the purposes of this travel assistance plan, a government or an international governmental political threat is extended to mean civil threats organization or to intimidate the public, or a caused by riots, strikes, or civil commotion. -

“Khosrov Forest” State Reserve

Strasbourg, 21 November 2011 [de05e_12.doc] T-PVS/DE (2012) 5 CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS GROUP OF SPECIALISTS -EUROPEAN DIPLOMA OF PROTECTED AREAS 9-10 FEBRUARY 2012, STRASBOURG ROOM 14, PALAIS DE L’EUROPE ---ooOoo--- APPLICATION PRESENTED BY THE MINISTRY OF NATURE PROTECTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA “KHOSROV FOREST” STATE RESERVE Document prepared by the Directorate of Culture and Cultural and Natural Heritage This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire - 2 - T-PVS/DE (2011) 5 Council of Europe European Diploma Area Information Form for candidate Sites Site Code (to be given by Council of Europe) B E 1. SITE IDENTIFICATION 1.1. SITE NAME “Khosrov Forest” State Reserve 1.2. COUNTRY Republic of Armenia 1.3. DATE CANDIDATURE 2 0 1 1 1.4. SITE INFORMATION 2 0 1 1 1 1 2 5 COMPILATION DATE Y Y Y Y M M D D 1.5. ADRESSES: Administrative Authorities National Authority Regional Authority Local Authority Name: “Environmental Project Name: Name: Implementation Unit” State Address: Address: Agency under the Ministry of Nature Protection of RA Address: 129 Armenakyan str., Yerevan, 0047 Republic of Armenia Tel.: Tel.: Fax.: Fax.: Tel.: +374 10 65 16 31 e-mail: e-mail: Fax.: +374 10 65 00 89 e-mail: [email protected] - 3 - T-PVS/DE (2011) 5 1.6. ADRESSES: Site Authorities Site Manager Site Information Centre Council of Europe Contact Name: “Khosrov Forest” State Name: “Khosrov Forest” State Name: “Environmental Project Reserve Reserve Implementation Unit” State Director Adress: : Kasyan 79 Agency -director (Mr. -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

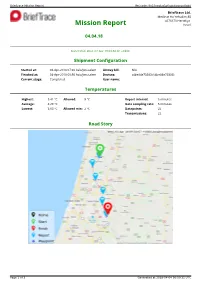

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

ICAN Experience Invitation

The International Community Action Network (ICAN) is planning its second edition of THE ICAN MIDEAST EXPERIENCE trip. This is no ordinary vacation to the Middle East HIGHLIGHTS INCLUDE: Day in Amman, including a visit of Al Zaatari Syrian refugee camp Home hospitality with families in Bedouin village of Lakiya Tour in Awa Jan (unrecognized village) Visits to Jaffa and Tel Aviv Guided tour of the ancient Nabatean city of Petra Enjoy some relaxation time at the Dead Sea Overnight in the Negev desert at Kibbutz Ruhama in Southern Israel Tours of religious and historic sites of the 3 Abrahamic religions of the world Meals with community leaders and activists along the way Visit ICAN centres in Sderot, East Jerusalem, Nablus, Amman and the West Bank This is NOT a fundraiser; it is a FRIENDRAISER. We would like to count you among our friends who most intimately know ICAN, understand how it works, spread the word about the need for such a unique and effective means of fostering peace in the region, and provide whatever other support you can. As such, the content will be fascinating, the experience will be unique, and the cost will be reasonable. Attached are the details on the itinerary and the cost. Please let us know whether you are ready to embark with us on The ICAN Experience, an experience of a lifetime! Yours in peace, David Auerbach & Stephen Hecht Co-Chairs ICAN Middle East Experience International Community Action Network (ICAN) The International Community Action Network (ICAN) is a program within McGill University's School of Social Work committed to creating a world in which all people share the same rights. -

Israel-Palestine Through the Lens of Game Theory

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Economics Department Working Paper Series Economics 2021 Land for peace? Israel-Palestine through the lens of game theory Amal Ahmad Department of Economics, University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/econ_workingpaper Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Ahmad, Amal, "Land for peace? Israel-Palestine through the lens of game theory" (2021). Economics Department Working Paper Series. 301. https://doi.org/10.7275/21792057 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics Department Working Paper Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Land for peace? Israel-Palestine through the lens of game theory Amal Ahmad∗ February 2021 Abstract Why have Israel and the Palestinians failed to implement a \land for peace" solution, along the lines of the Oslo Accords? This paper studies the applica- tion of game theory to this question. I show that existing models of the conflict largely rely on unrealistic assumptions about what the main actors are trying to achieve. Specifically, they assume that Israel is strategically interested in withdrawing from the occupied territories pending resolvable security concerns but that it is obstructed from doing so by violent Palestinians with other objec- tives. I use historical analysis along with bargaining theory to shed doubt on this assumption, and to argue that the persistence of conflict has been aligned with, not contrary to, the interests of the militarily powerful party, Israel. -

ICOMOS Sent a Letter to the State Party on 6 Armenian Monastic Ensembles (Iran) December 2007 About the Following Points

Additional information requested and received from the State Party: ICOMOS sent a letter to the State Party on 6 Armenian monastic ensembles (Iran) December 2007 about the following points: No 1262 - Request for further information about the authenticity of the reconstruction of the Chapel of Dzordzor following its removal to another site; - Request for more detailed maps for the nominated Official name as proposed properties, showing in particular if the villages and by the State Party: The Armenian Monastic Ensembles cemeteries are included; of Iran - Request for maps and description sheets of the Location: Provinces of West Azarbayjan and nominated villages and cemeteries; East Azarbayjan - Request for information about tourism development Brief description: projects linked to the nominated property; The monastic ensembles of St. Thaddeus and St. - Request for an impact study concerning economic Stepanos, and the Chapel of Dzordzor, are the main development projects for the Jolfa zone near St. heritage of the Armenian Christian culture in Iran. They Stepanos; were active over a long historical period, perhaps from the origins of Christianity and certainly since the 7th - Request for a schedule for the introduction of the century. They have been rebuilt several times, either as a management plan. result of regional socio-political events or natural disasters (earthquakes). To this day, they remain in a ICOMOS sent a second letter to the State Party on 17 semi-desertic environment in keeping with the original January 2008 to ask for additional information about the landscape. role of the region in the management plan. Category of property: In reply from the State Party, ICOMOS received on 27 February 2008 a set of plans and a dossier answering its In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in questions. -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

West Nile Virus (WNV) Activity in Humans and Mosquitos

West Nile virus (WNV) activity in humans and mosquitos Updated for 28/11/2016 In the following report, a human case patient who is defined as "suspected" refers to a patient whose lab test results indicate a possibility of infection with WNV, and a human case patient who is defined as "confirmed" refers to a patient whose lab test results show a definite infection with WNV. The final definition status of a patient who initially was diagnosed as "suspected" may be changed to "confirmed" due to additional lab test results that were obtained over time. Cumulative numbers of human case patients and mosquitos positive for WNV by location: Until the 28/11/2016, human cases with WNF have been identified in 54 localities and WNV infected mosquitos were found in 6 localities. אגף לאפידמיולוגיה Division of Epidemiology משרד הבריאות Ministry of Health ת.ד.1176 ירושלים P.O.B 1176 Jerusalem [email protected] [email protected] טל: 02-5080522 פקס: Tel: 972-2-5080522 Fax: 972-2-5655950 02-5655950 Table showing WNV in human by place of residency: Date sample Diagnostic status Locality No. Locality Health district received in lab according to lab 1 Or Yehuda 31/05/2016 Suspected Tel Aviv Or Yehuda 02/06/2016 Suspected Tel Aviv 2 Or Aqiva 17/07/2016 Suspected Hadera 3 Ashdod 19/09/2016 Suspected Ashqelon Ashdod 27/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon 4 Ashqelon 29/08/2016 Suspected Ashqelon Ashqelon 05/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 08/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 13/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon Ashqelon 22/09/2016 Confirmed Ashqelon -

Reflections on Camp David at 40

Reflections on Camp David at 40 How the Camp David Accords became a limited Egyptian–Israeli peace effort that ultimately transformed Arab–Israeli relations across the Middle East By William B. Quandt hen President Jimmy Carter and his foreign policy team began to address the Arab–Israeli conflict in early 1977, they had several W important reference points in mind. First was the vivid memory of the 1973 October War and the threat it had posed to international security as well as economic prosperity. No one wanted to see a repeat of such a dramatic and dangerous conflict. In addition, there was the beginning of a serious diplomatic process begun under the careful guidance of Henry Kissinger, secretary of state for both Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Three agreements on the disengagement of military forces had been reached, two between Egypt and Israel, and one between Syria and Israel, which set the stage for Carter’s own diplomatic efforts in the Arab–Israeli arena. Finally, the United States had good working relations with most of the key parties in the conflict, other than the Palestinians, and Carter was eager to deepen those relations in pursuit of peace in the Holy Land, something that was particularly appealing to him as a devout Christian. All of this meant that the team around the president, which included several participants in the Brookings Report of 1975, were predisposed to support a U.S.-led effort to achieve a comprehensive solution to the Arab–Israeli conflict, including some form of self-determination for the Palestinians—the main goals identified by the report. -

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land The maronite church of Our Lady of Annunciation in Nazareth Deacon Habib Sandy from Haifa, in Israel, presents in this article one of the Catholic communities of the Holy Land, the Maronites. The Maronite Church was founded between the late 4th and early 5th century in Antioch (in the north of present-day Syria). Its founder, St. Maron, was a monk around whom a community began to grow. Over the centuries, the Maronite Church was the only Eastern Church to always be in full communion of faith with the Apostolic See of Rome. This is a Catholic Eastern Rite (Syrian-Antiochian). Today, there are about three million Maronites worldwide, including nearly a million in Lebanon. Present times are particularly severe for Eastern Christians. While we are monitoring the situation in Syria and Iraq on a daily basis, we are very concerned about the situation of Christians in other countries like Libya and Egypt. It’s true that the situation of Christians in the Holy Land is acceptable in terms of safety, however, there is cause for concern given the events that took place against Churches and monasteries, and the recent fire, an act committed against the Tabgha Monastery on the Sea of Galilee. Unfortunately in Israeli society there are some Jewish fanatics, encouraged by figures such as Bentsi Gopstein declaring his animosity against Christians and calling his followers to eradicate all that is not Jewish in the Holy Land. This last statement is especially serious and threatens the Christian presence which makes up only 2% of the population in Israel and Palestine.