University of Cincinnati Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati 2016 Campus Climate Survey Results Summary

University of Cincinnati 1 University of Cincinnati 2016 Campus Climate Survey Results Summary The State of Ohio’s Changing Campus Culture Initiative seeks to strengthen its ability to better respond to, and ultimately prevent, sexual assault on the state’s college campuses. In the spring 2016, all Ohio campuses were encouraged to participate in recommendation #1 in the Changing Campus Culture report: use data to guide action. In addition to completing a comprehensive campus climate survey, Ohio campuses were also asked to disseminate 15 common benchmark questions. The purpose of the benchmark questions was to provide the Ohio Department of Higher Education with a common set of data to measure statewide progress in addressing prevention and response to sexual violence, and to track trends over time. While campuses were free to determine which climate survey best fit their campus community, the benchmark questions were the same to allow for comparison between one campus and others of similar type. Methodology and Sample Data collection began in the 2016 spring semester and ended by June 2016. Institutions collected data in various ways, including through paper surveys and electronically. All responses were anonymous. Each participating school was asked to gather data on the benchmark questions along with provided demographic questions. Response scales for the benchmark questions and demographic questions varied slightly for some institutions, and any questions with substantively different response scales were excluded from the aggregate analyses. 14 public university main campuses, 23 community/state/technical colleges, and 35 private institutions participated in the survey. The overall sample included 23,240 students across the sampled 71 higher education institutions. -

Pioneering Transformations

PIONEERING TRANSFORMATIONS Report on Engagement & Post-Graduation Plans Classes of 2016 and 2017 INTERNSHIPS STUDY ABROAD • More than 120 internships were completed for academic credit. • Fall 2016: 6 (Australia, Ireland, Spain (2), New Zealand, England) • The majority were paid internships. • Fall 2016: Dubai SPE Conference • Marietta College received two grants to help provide monetary • Spring 2017: 3 (China, Germany, Scotland) incentives for employers and students who participate in internships. • Spring 2017: LEAD trip to Peru • Summer 2017: 2 (Korea and Spain) As part of the McDonough Center’s 30th Anniversary celebrations, faculty EVANS ENDOWED INTERNSHIP PROGRAM 2017: took a group of students and alumni to the highlands of Peru. They spent Amanda Rogers is the recipient of The 2017 Robert Evans Internship two weeks exploring the country, which included hiking to the summit of Endowment. Amanda, a double major in Economics and Management, Machu Picchu and visiting the floating islands of Lake Titicaca. Marietta spent the summer in Cleveland interning with Insight2Profit, a fast-growing College Professors Dave Brown, Robert McManus and Dave McShaffrey price consulting and technology firm serving domestic and international led the trip. This trip fulfilled the international experiential education B2B manufacturers, distributors and service providers. The Robert Evans requirement for the International Leadership Studies Major. Internship Endowment was set up by an alumnus several years ago and awards $5,000 to one qualified student who participates in a summer internship at a for-profit organization, specifically a major national or global organization. The $5,000 can be used for relocation, travel, housing, meals, related equipment purchases and other living expenses. -

2004-2005 Heidelberg College Catalog Heidelberg 310 East Market Street College Tiffin, Ohio 44883-2462 1.800.Heidelberg

Non-Profit Org. Heidelberg U.S. Postage PAID College Heidelberg 2004-2005 Heidelberg College Catalog Heidelberg 310 East Market Street College Tiffin, Ohio 44883-2462 1.800.Heidelberg www.heidelberg.edu 2004 - 2005 CATALOG Academic Year Calendar Introduction ' Semester I 2004-2005 1 Sun. Aug. 29 First-year students and transfers arrive Mon. Aug. 30 Registration verification Tues. Aug. 31 Classes begin Thur. Oct. 14 Long weekend recess begins after last class Mon. Oct. 18 Classes resume Tues. Nov. 23 Thanksgiving recess begins after last class Mon. Nov. 29 Classes resume Fri. Dec. 10 Classes end Mon. Dec. 13 Final exams begin Thur. Dec. 16 Christmas recess begins after last exam ' Semester II 2004-2005 Sun. Jan. 9 Registration verification Mon. Jan. 10 Classes begin Mon. Jan. 17 No classes—Martin Luther King Day Thur. Mar. 10 Spring recess begins after last class Tues. Mar. 29 Classes resume Thur. May 5 Classes end Fri. May 6 Final exams begin Wed. May 11 Final exams end Sun. May 15 Baccalaureate, Undergraduate and Graduate Commencement ' Summer 2005 Mon. May 23 Term 1 classes begin Fri. June 24 Term 1 classes end Mon. June 27 Term 2 classes begin Fri. July 29 Term 2 classes end Mon. May 23 Term 3 classes begin Fri. July 29 Term 3 classes end Sources of Information HEIDELBERG COLLEGE, Tiffin, Ohio 44883-2462 2 TELEPHONE SUBJECT OFFICE AREA CODE: 419 Admission Vice President for Enrollment 448-2330 Advanced Standing Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of the College 448-2216 Alumni Affairs Director of Alumni and Parent Relations -

Policy Manual

University of Cincinnati Use of Facilities Policy Manual 8/2008 * [The1 information contained herein was prepared by a committee appointed by the President of the University of Cincinnati and has been reviewed by the Office of General Counsel.] TABLE OF CONTENTS Access to University Buildings ………………………………………………………….. 3 Use of Storage Facilities on Campus…………………………………………………….. 3 General Policies Pertaining to the Use of University Facilities………………………… 4 Responsibilities of all Groups/Individuals……………………………………………….. 4 Rental Charges and Expenses…………………………………………………………….. 4 Safety and Security……………………………………………………………………….. 5 Political Programs and Activities…………………………………………………………. 5 Fund Raising……………………………………………………………………………… 6 Distribution of Printed Materials, Publicity, Promotional Methods, Posted Materials… 6 Bulletin Boards…………………………………………………………………………… 6 Banners…………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Recruiting and Information Tables……………………………………………………….. 7 Speakers, Speech and Assembly…………………………………………………………., 8 Academic Facilities……………………………………………………………………… 9 East Campus………………………………………………………………………………. 9 West Campus……………………………………………………………………………... 9 Branch Campuses………………………………………………………………………… 10 Non-Academic Facilities………………………………………………………….............. 12 Athletic Facilities………………………………………………………………………….. 16 Area Specific Facilities…………………………………………………………………… 17-44 Appendices………………………………………………………………………………… 44 Appendix A - Definitions………………………………………………………………… 44 Appendix B – Individual Policies 47 Alcohol Policy…………………………………………………………………….. -

Black Women at the University of Cincinnati, 1897-1940

Winter 1985 Educated Pioneers 21 Educated Pioneers: Black Women at the University of Cincinnati, 1897-1940 Delores Thompson and taught Black youngsters at the Harriet Beecher Stowe School.2 Lyle Koehler The attitude of college administrators toward the admission of Blacks at U.C. is unknown. Certainly Charles McMicken, an early commission merchant whose considerable This year the University of Cincinnati is 166 funds actually laid the foundation for the University, did not years old. Founded in 1819 as the Cincinnati College, it favor their enrollment (even though he himself had an became the University of Cincinnati in 1890. Despite its illegitimate Mulatto son). McMicken's will in 1855 provided long history, Black Americans have not had much access to for "two colleges for the education of White boys and girls." U.C.'s halls until recent times. However, as early as 1891 It is not known whether University officials endorsed some Blacks did receive degrees from this institution. The McMicken's idea that U.C. should be for Whites, but the history of these early Black pioneers deserves attention and enrollment of at least two Blacks before 1893 was apparently this paper provides descriptions of the educational experi- done against the spirit of McMicken's will. However officials ence of Cincinnati Black women attending the University at this institution, like those at other universities around the between 1897 and 1940. nation, generally adopted a laissez-faire attitude and made no During the nineteenth century less than four effort to attract Black students. Some may even have shared percent of all college age Americans actually attended any the ideas of Conservative Social Darwinists who asserted college or university. -

Initial Placement of Athletic Training Graduates

Initial Placement of Athletic Training Graduates Class of 2017 Cierra Bloom- Athletic Training intern, Spartanburg Methodist College Mariah Orr- Physician Assistant program, Marietta College Nikki Young- Medical School, Ohio University Class of 2016 Tanner Bleakly- Graduate School, West Virginia Wesleyan Austin Eppley- Graduate School, Clayton State University Luis Garcia- Employed as Personal Fitness Trainer Jayla Graves- Clinic Outreach/Mercy Hospital/Willard High School Anna Lee Haviland- Graduate School, South Florida University Madonna Lott- Athletic Trainer, Marietta High School Class of 2015 Gretchen Baisden- PA school, Marietta College Jess Brogran- Graduate School, California University of Pennsylvania Emily Estrich- Employed other than as an Athletic Trainer Carissa Emerick- PT School. Wheeling Jesuit University Amanda Lusky- Intern position Wide World of Sports Disney. Graduate School, Otterbein University Whitnie Pinkston- Graduate School, Ohio Valley University Shelby Preston- Chiropractic School, National University of Health Science Juliam Rivera- Employed other than as an Athletic Trainer Todd Sabol- Graduate School, Ohio University Jenna Smith- Rehab Aide UPMC Outpatient Physical Therapy Class of 2014 Katie Clark- Graduate School, California University of Pennsylvania Aimee Cline-Graduate School, Ohio University Beth Malony- Nursing School, Riverside College of Health Science. Newport News, VA Luke Milller- Intern position, Evansville University Kelsie Sparber- Graduate School. California University of Pennsylvania Class -

“NEXT” Apprenticeship Program Projected

University of Cincinnati – Cincinnati, OH Award Amount: $11,893,184 Project Name: “NEXT” Apprenticeship Program Projected Apprentices to Be Served: 10, 476 Industry Focus: Information Technology Private Sector Partners include a business consortium consisting of Curvature, Northrop Grumman, Kinetic Vision, Pepulab, GE Aviation, IBM, and Lubrizol. Type(s) of Apprenticeship Program Proposed: Registered Apprenticeship Program (RAP) The NEXT project seeks to build robust pathways enabling unemployed and underemployed underrepresented minority populations (URMs), as well as women, veterans, ex-offenders, nontraditional learners and others underrepresented in the IT field, to secure middle- and high- skilled jobs in the high-paying IT sector. The project incorporates flexible educational and experiential (i.e., work-integrated) opportunities tailored to a wide variety of individuals, and incorporates 22 nationally portable, industry-recognized credentials from Cisco, CompTIA, and the IBM Skills Academy. The project is leveraging the University of Cincinnati’s (UC) experience leading the Cooperative Education Model, which UC founded in 1906, to take the NEXT apprenticeship model to a national scale. Strategies include incorporating multiple education pathways with experiential learning components, expanding regional campus programs to provide industry certifications, and redefining the co-op model to fit the new, competency-based apprenticeship models. For instance, the project is convening industry and education partners at UC’s Remote Work and Employer Learning Center to create new virtual, contract-based, part- and full-time apprenticeships in an experimental setting. Alongside the well-established co-op model, the project is building a framework based on European Union models of skills development, as well as occupation-based training models, boot camps, and workshops in such fields as Cognitive & Artificial Intelligence, Block Chain, and Quantum Computing. -

List of Colleges in Ohio

CollegesColleges inin ohioohio Main CAMPUSES Main CAMPUSES Main CAMPUSES Main CAMPUSES Main CAMPUSES 1. University of Akron 39. Bluton University 59. Antioch University 90. Marietta College 103. Capital University 2. Allegheny Wesleyan College 40. Bowling Green State University 60. The Art Academy of Cincinnati 91. Muskingum College 104. Circleville Bible College 3. Ashland University 41. The Deance College 61. The Athenaeum of Ohio 92. Ohio University 105. Columbus College of Art & Design 4. Baldwin-Wallace College 42. University of Findlay 62. Cedarville College 93. University of Rio Grande 106. Denison University 5. Case Western Reserve University 43. Heidelberg College 63. Central State University 94. Shawnee State University 107. Franklin University 6. Laura & Alvin Siegal College of Judaic 44. Lourdes College 64. Cincinnati Bible College & Seminary 108. Kenyon College Studies 45. Medical College of Ohio at Toledo 65. Cincinnati Christian College UNIVERSITY BRANCH CAMPUSES 109. Mt. Carmel College of Nursing 7. Cleveland Institute of Art 46. Ohio Northern University 66. University of Cincinnati 95. Ohio University – Belmont 110. Mt. Vernon Nazarene College 8. Cleveland Institute of Music 47. Tin University 67. University of Dayton 96. Ohio University – Chillicothe 111. Ohio Dominican College 9. Cleveland State University 48. University of Toledo 68. God’s Bible College 97. Ohio University – Ironton 112. The Ohio State University 10. David N. Myers College 69. Miami University 98. Ohio University – Zanesville 113. Ohio Wesleyan University 11. Franciscan University of Steubenville 70. College of Mount St. Joseph 114. Otterbein College 12. Hiram College UNIVERSITY BRANCH CAMPUSES 71. Temple Baptist College Community/Technical Colleges 115. Pontical College Josephinum 13. -

Class of 2015

Class of 2015 University Name Program of Study General Area of Study (IPEDS) Degree Sought Health-related knowledge and Master of Business Administration Bluffton University skills (M.B.A.) English language and Bowling Green State University Rhetoric and Writingliterature/letters Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Business, management, marketing, and related support Master of Business Administration EU Business School Sport Management services (M.B.A.) Farrier Research Center Farrier school Health-related knowledge and George Washington University Epidemiology skills Other Master Degree International business college Veterinary technician Other Other Health professions and related Iowa State University College Of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Medicine programs Other Doctoral Degree Health professions and related Kettering College Biology programs Other Master Degree Kettering College Occupational Therapy Other Other Doctoral Degree Health professions and related Kettering College of Medical Arts Physician Assistant programs Master of Science (M.S.) Biological and biomedical Lincoln Memorial University Master of Science sciences Lincoln Memorial University-College of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Medicine Other Other Doctoral Degree Doctor of Veterinary Health professions and related Michigan State University Medicine programs Other Professional Degree Biological and biomedical Mississippi State University Biology sciences Other Doctoral Degree Health professions and related Nuclear Education Online Nuclear pharmacy programs Certificate Health -

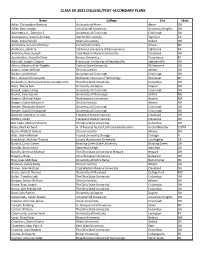

Class of 2021 College & Post Secondary Plans-1

CLASS OF 2021 COLLEGE/POST-SECONDARY PLANS Name College City State Adler, Christopher Bennett University of Akron Akron OH Adler, Ryan Joseph John Carroll University University Heights OH Adornetto Jr., Dominic S. University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Alexopoulos, Vassilis Andreas Stanford University Stanford CA Allen, Drew Patrick Miami University Oxford OH Amendola, Connor Anthony Cornell University Ithaca NY Anderson, DeVar G California University of Pennsylvania California PA Anthony, Ryan Joseph Case Western Reserve University Cleveland OH Apostolakis, Aristotle Peter Brown University Providence RI Ashcraft, Joseph Clayton Franciscan University of Steubenville Steubenville OH Atkins, Masario Allen-Rogelio Central State University Wilberforce OH Austin, Aidan William Ohio University Athens OH Barker, Ian Michael Universtiy of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Bart, Jackson Christopher Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester NY Barzacchini, Nicholas Anthony Joseph John The Ohio State University Columbus OH Basic, Nikola Ivan University of Dayton Dayton OH Baszuk, Logan James University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Becker, John Gerald University of Mississippi Oxford MS Bednar, Michael Adam Northeastern University Boston MA Beegan, Caden Benjamin Ohio University Athens OH Bender, Alexander Daniel University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Bender, David Christopher University of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Bennett, DeAndre Cristian Cleveland State University Cleveland OH Betters, Owen Cleveland State University Cleveland OH Biernacki, Michael Vincent -

Lifeline, Winter 2013

Winter 2013 ALUMNI ANNOUNCEMENTS PROGRAM STAFF We’d love to let your fellow alumni know what you are doing. Send us news about your life DIRECTOR and your practice to include in Alumni Announcements for our next edition of LifeLine! Just fill out our short Alumni Spotlight Survey at www.surveymonkey.com/s/UDalumspotlight. Kathleen Scheltens, Ph.D. [email protected] LIFELINE ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Premedical Programs Alumni Newsletter Julie Simon, Ph.D. HEALTHCARE CONNECTION [email protected] ADMINISTRATION ASSISTANT WHAT’S HAPPENING ON CAMPUS? Successful candidates at health professional our survey at www.surveymonkey.com/s/ AnnMarie Davies schools need more than a good GPA and healthcareconnection. WRITTEN & EDITED high test scores; they need to observe and University of Dayton/Miami Valley Hospital experience work in healthcare first-hand. By completing the survey, you will be joining Kathleen Scheltens, Ph.D. DIRECTOR’S WELCOME “Healthcare Connection.” Once we receive HEALTHCARE SYMPOSIUM As the University of Dayton continues to your survey, we will periodically contact you YOUR COMMENTS AND expand the geographical diversity of the to see if you are interested and able to have student body, the premedical programs office a student shadow you. Any information you SUBMISSIONS ARE ENCOURAGED! March 23rd is the date of the fourth an- Applications” was delivered by Dr. Happy New Year! I hope the new year finds would like to expand our pool of alumni who share with us will be kept strictly confidential Please visit our website for more nual UD/Miami Valley Hospital Health- Harold Koenig, Director of the Center you well. -

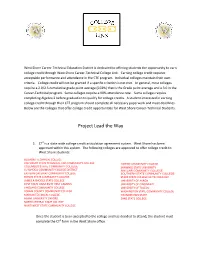

Project Lead the Way

West Shore Career-Technical Education District is dedicated to offering students the opportunity to earn college credit through West Shore Career-Technical College Link. Earning college credit requires acceptable performance and attendance in the CTE program. Individual colleges maintain their own criteria. College credit will not be granted if a specific criterion is not met. In general, most colleges require a 2.0/2.5 cumulative grade point average (CGPA) that is the Grade point average and a 3.0 in the Career-Technical program. Some colleges require a 90% attendance rate. Some colleges require completing Algebra 2 before graduation to qualify for college credits. A student interested in earning college credit through their CTE program should complete all necessary paperwork and meet deadlines. Below are the colleges that offer college credit opportunities for West Shore Career-Technical Students. Project Lead the Way 1. CT2 is a state wide college credit articulation agreement system. West Shore has been approved within this system. The following colleges are approved to offer college credit to West Shore students: BELMONT TECHNICAL COLLEGE CINCINNATI STATE TECHNICAL AND COMMUNITY COLLEGE OWENS COMMUNITY COLLEGE COLUMBUS STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE SHAWNEE STATE UNIVERSITY CUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICT SINCLAIR COMMUNITY COLLEGE EASTERN GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE SOUTHERN STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE EDISON STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE STARK STATE COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY JAMES A RHODES STATE COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF AKRON KENT STATE UNIVERSITY-KENT CAMPUS UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI LAKELAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF TOLEDO LORAIN COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE WASHINGTON STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE MARION TECHNICAL COLLEGE YOUNGSTOWN STATE MIAMI UNIVERSITY OXFORD ZANE STATE COLLEGE NORTH CENTRAL STATE COLLEGE NORTHWEST STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE Once the student is been accepted to the college and has decided to attend, the student must complete the CT2 form in the West Shore office.