English 2080 S 19 Viewing Questions on the Twoothellos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

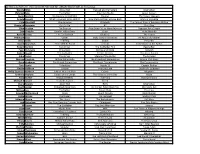

American Players Theatre Production History

American Players Theatre Production History 1980 A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Ed Berkeley Titus Andronicus by William Shakespeare Directed by Ed Berkeley 1981 King John by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Mik Derks The Comedy of Errors by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Mik Derks The Two Gentleman of Verona by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Mik Derks A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Mik Derks Titus Andronicus by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Mik Derks 1982 Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare Directed by Fred Ollerman & Mik Derks Titus Andronicus by William Shakespeare Directed by Mik Derks The Comedy of Errors by William Shakespeare Directed by Fred Ollerman & Mik Derks The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare Directed by Fred Ollerman & Mik Derks The Two Gentleman of Verona by William Shakespeare Directed by Fred Ollerman A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Sandra Reigel-Ernst 1983 Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare Directed by Mik Derks Tamburlaine the Great by Christopher Marlowe Directed by Mik Derks Love's Labour's Lost by William Shakespeare Directed by Fred Ollerman The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare Directed by Fred Ollerman A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso 1984 Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare Directed by Anne Occhiogrosso & Randall -

Performing Othello in South Africa Natasha Distiller

Authentic Protest, Authentic Shakespeare, Authentic Africans: Performing Othello in South Africa Natasha Distiller ugh Quarshie famously declared Othello a play that black actors Hshould avoid: “If a black actor plays Othello does he not risk making racial stereotypes seem legitimate… namely that black men… are over- emotional, excitable and unstable?”1 Ben Okri, referencing the reception of Shakespeare’s tragedy by critics and audiences,2 said that if Othello were not originally a play about race (as indeed it was not in the modern sense of the term), its history has made it one.3 By now, Othello both invokes and confounds modern notions of race and racial difference, speaking powerfully to the long history of misogyny it has facilitated.4 The play also points to the ways in which race and gender are imbricated in one another and co-depend.5 The meaning of Desdemona’s whiteness and femininity depend on each other, as do Othello’s blackness and masculinity. As Celia Daileader has pointed out, Desdemona’s punishment for being an unruly woman is symbolized by and through Othello’s racial identity.6 One might say that Othello both is and is not about race and racial difference, a play that invokes a relation between gender and the range of human cultures, religions, civic belongings, and/or appearances that we now encode as “race.” Whichever ideological frame one chooses to read through (an early modern construction of Moorishness, a postmodern antiracism, a feminist awareness of domestic violence, a combination of these, or any of the other possible lenses one could apply), to understand the play one must recognize the ways it explores the experience of difference as emotionally fraught at best, potentially dangerous at worst. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Some Thoughts Surrounding 2016Production of the Tempest

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DSpace at Waseda University Some thoughts surrounding 2016 production of The Tempest UMEMIYA Yu The following note shows the result of an on going research on the play by William Shakespeare: The Tempest. The 2016 production at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), one of the leading theatre companies in England, demonstrated another innovative version of the play on their main stage in Stratford-upon-Avon, followed by its tour down to Barbican theatre in London in 2017. It did not include an extraordinary interpretation or unique casting pattern but demonstrated the extended development of technology available on stage. This note introduces the feature and the reception of the production in the latter half, with a brief summary of the play and a survey of the performance history of The Tempest in the first half. The story of The Tempest Compared to other plays by Shakespeare, The Tempest is a rare example that follows the classical idea of three unities of time, place and action, deriving from 1 Aristotle, then prescribed by Philip Sydney in Renaissance England . The similar 2 structure has already practiced in The Comedy of Errors in 1594 , but while this early comedy is often described as a simple farce, The Tempest contains various complications in terms of plots and theatrical possibilities. The story of The Tempest opens with a storm at sea, conjured by the magic of Prospero, the main character of the play. He is manipulating the tempest from the 一二七nearby island where he lives with his daughter, Miranda, and shares the land with two other fantastic creatures, Ariel and Caliban. -

Theatre Reviews

Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance Volume 8 Article 10 November 2011 Theatre Reviews Coen Heijes University of Groningen, the Netherlands Xenia Georgopoulou Department of Theatre Studies of the University of Athens, Greece Nektarios-Georgios Konstantinidis French Department of the University of Athens, Greece Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/multishake Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Heijes, Coen; Georgopoulou, Xenia; and Konstantinidis, Nektarios-Georgios (2011) "Theatre Reviews," Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance: Vol. 8 , Article 10. DOI: 10.2478/v10224-011-0010-9 Available at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/multishake/vol8/iss23/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance , vol. 8 (23), 2011 DOI: 10.2478/v10224-011-0010-9 Theatre Reviews The Tempest . Dir. Janice Honeyman. The Baxter Theatre Centre (Cape Town, South Africa) and the Royal Shakespeare Company (Stratford-upon- Avon, United Kingdom). a Reviewed by Coen Heijes The Multiple Faces of a Multicultural Society The last twenty lines of The Tempest are spoken by Prospero. They are an epilogue in which he asks the audience both for applause and for forgiveness in order to set him, the actor, free. The stage directions indicate that Prospero is by now alone on stage, all the other characters having left in the course of scene 5.1. -

Dr John Kani

CITATION: BONISILE JOHN KANI One of the pioneers of contemporary theatre in South Africa, John Kani’s legacy is one shaped by an extraordinary command of language, storytelling and performance. It is a legacy that has been embedded in performance cultures, theatres and learning spaces across the globe – his body of work studied, performed and archived for future generations. Kani’s deft storytelling, emboldened performances and frank social gaze are a testament to the artist’s broad expressive range, skilled delivery and insightful representation of reality. However, his mastery of acting, directing and writing does not alone encapsulate his significance as an artist; it is his chronicling of South Africa’s historical journey through his art over the last five decades that is of even more importance to our country and beyond. Kani’s unwavering commitment towards social justice is rooted in his creative research through theatre, television and film, as well as his civil society engagements, providing a complex, humane socio- political critique of South Africa’s relational landscape. Bonisile John Kani was born on 30 August 1943 in the Port Elizabeth township of New Brighton, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province. His prolific career grew from performance to writing and dramaturgy, to directing in theatre, to television and, more recently, to working in film. Today, Kani is an internationally acclaimed actor and writer. His first major encounter with theatre was through the ground-breaking Serpent Players in 1965 in New Brighton. Here, the formidable trio of Kani, Winston Ntshona and Athol Fugard took root, a relationship that saw the creation of Sizwe Banzi is Dead and The Island, which were first performed in the early 1970s. -

Redalyc.Post-Apartheid Cinema: a Thematic and Aesthetic Exploration

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Botha, Martin P. Post-apartheid cinema: A thematic and aesthetic exploration of selected short and feature films Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 61, julio-diciembre, 2011, pp. 225-267 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348699009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2011n61p225 POST-aPARTHEID CINEMA: A THEMATIC AND AESTHETIC EXPLORATION OF seLECTED SHORT AND FEATURE FILMS Martin P. Botha1 University of Cape Town Abstract The revival in short filmmaking in post-apartheid cinema has thus far received little attention by academic scholars. The article is an attempt to describe, contextualise and analyse the highlights of South African short filmmaking by focusing on thematic and aesthetic developments in post-apartheid cinema. Hundreds of short fiction and nonfiction films have been made in South Africa since 1980. The themes of most of these films were initially limited to anti-apartheid texts, which were instruments in the anti-apartheid struggle. During the late 1980s and early 1990s short filmmakers have also explored themes other than apartheid, for example equal rights for gay and lesbian South Africans. -

Rsc.Org.Uk/Access 01789 403436 February – September 2019 Stratford-Upon-Avon

ACCESS MATTERS Welcome to the next edition of Access Matters, where you can find out about our access provision and our forthcoming assisted performances. What’s on February – September 2019 Stratford-upon-Avon rsc.org.uk/access 01789 403436 February – September 2019 Stratford-upon-Avon As You Like It The Taming of the William Shakespeare Shrew Royal Shakespeare Theatre William Shakespeare 14 February – 31 August Royal Shakespeare Theatre Come into the forest; dare to change 8 March – 31 August your state of mind. In a reimagined 1590, England is a Rosalind is banished, wrestling with her matriarchy. Baptista Minola is seeking to heart and her head. With her cousin by sell off her son Katherine to the highest her side, she journeys to a world of exile bidder. Cue an explosive battle of the where barriers are broken down and all sexes in this electrically charged love can discover their deeper selves. story. Director Kimberley Sykes (Dido, Queen Justin Audibert (Snow in Midsummer, of Carthage, 2017) directs a riotous, 2017; The Jew of Malta, 2015) turns exhilarating version of Shakespeare’s Shakespeare’s fierce, energetic comedy romantic comedy. of gender and materialism on its head to offer a fresh perspective on its portrayal of hierarchy and power. Captioned Performance Audio Described Performance Audio Described Performance Captioned Performance CAP CAP Friday 26 April, 7.15pm Saturday 22 June, 1.15pm Tuesday 30 April, 7.15pm Saturday 3 August, 1.15pm Relaxed Performance Captioned Performance Captioned Performance Semi-integrated British -

Stringcaesar – the Turning Point Foundation 1 Contents

StringCaesar – The Turning Point Foundation 1 Contents 3. Our vision 5. Our mission 7. What we aim to do Plans for 2010 Looking ahead to 2011 21. Who we are Artistic Director, World Theatre Season Director, Prison Film And Theatre Liaison, Business, Commercial and Charitable Director Patrons, Hon. Founder members, Trustees, Artistic Board, Trust details 30. Our unique history StringCaesar – The movie 36. Appendices A history of successful prison workshops Specific aims within Pollsmoor Letters of recommendation about the prison workshops Some facts about about South African Prisons Vision for ongoing film and theatre workshops in Pollsmoor Prison CVs StringCaesar – The Turning Point Foundation 2 Our vision StringCaesar – The Turning Point Foundation 3 StringCaesar – The Turning Point Foundation is a trust, the aim of which is to build a creative space, directed by talented artists, for the City of Cape Town’s underprivileged to learn and grow writing skills/ performance and production skills/interaction and communication skills. The poor. The so-called ordinary. Great artists, local, national, international. Together forming a creative hub for both the city and the wider national and international community. StringCaesar – The Turning Point Foundation 4 Our mission StringCaesar – The Turning Point Foundation 5 To inspire and develop the artistic talents and interactional skills of individuals in underprivileged communities and prisons in South Africa To use the performing arts as a catalyst for social and economic development and upliftment -

Acting 4 Actor List

ACTING 4 ACTOR LIST - FILM CHOICES FOR NON-MT LIBRARY SELECTIONS (ie Streaming) Woody Allen Annie Hall Hannah and Her Sisters Manhattan Christian Bale The Fighter American Hustle Laurel Canyon Javier Bardem No Country for Old Men Biutiful The Dancer Upstairs Angela Bassett What's Love Got to Do With It How Stella Got Her Groove Back Waiting to Exhale Cate Blanchett Blue Jasmine Elizabeth The Curious Case of Benjamin Button Chadwick Boseman Get On Up 42 Draft Day Ellen Burstyn The Exorcist Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore Requiem for a Dream Don Cheadle Devil in a Blue Dress Crash Hotel Rwanda Russell Crowe L.A. Confidential Gladiator The Insider Penelope Cruz Volver Vicky Cristina Barcelona All About My Mother Viola Davis The Help Doubt Prisoners Daniel Day Lewis There Will Be Blood Lincoln In the Name of the Father Robert De Niro Taxi Driver The Godfather Pt 2 Raging Bull Faye Dunaway Chinatown Bonnie and Clyde Network Robert Duvall The Godfather Tender Mercies The Great Santini Jodie Foster Taxi Driver Silence of the Lambs The Accused Morgan Freeman Million Dollar Baby The Shawshank Redemption Driving Miss Daisy Gene Hackman The French Connection The Royal Tenenbaums The Conversation Tom Hanks Philadelpia Apollo 13 Captain Phillips Dustin Hoffman Tootsie The Graduate Death of a Salesman Philip Seymour Hoffman A Most Wanted Man Capote Magnolia Anthony Hopkins Silence of the Lambs The Remains of the Day Nixon Holly Hunter Broadcast News The Piano Raising Arizona Michael B Jordan Fruitville Station Creed Diane Keaton Annie Hall Reds Manhattan -

Kennedy Center

KENNEDY CENTER Gold Medal in the Arts SATURDAY,Gala APRIL 14, 2018 ZEITZ MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART AFRICA CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA Stephanie and Karel Komárek, Co-Chairs The Kennedy Center International Committee on the Arts welcome you to the Kennedy Center Gold Medal in the Arts Gala celebrating Basil J.R. Jones and Adrian P. Kohler John Kani Sibongile Khumalo Dr. Gcina Mhlophe McCoy Mrubata Gold Medal in the Arts Past Recipients 2005 ST. PETERSBURG 2012 MADRID OLIVIA DE HAVILLAND, PEDRO ALMODÓVAR, VALERY GERGIEV, MARTHA SARA BARAS, PLÁCIDO INGRAM, IRWIN JACOBS, DOMINGO, PACO PEÑA, MÆRSK MCKINNEY MØELLER, TAMARA ROJO TREVOR NUNN 2013 PRAGUE 2006 LONDON JIŘÍ BĚLOHLÁVEK, SOŇA DARCEY BUSSELL, ČERVENÁ, KAREL KOMÁREK, MICHAEL CAINE, JUDI DENCH, JR.,MAGDALENA KOŽENÁ JEREMY IRONS, JACOB ROTHSCHILD, LILY SAFRA 2014 UAE HOOR AL-QASIMI, BADR 2007 BEIJING JAFAR, QUINCY JONES, SONG ZUYING, ARIF AND FAYEEZA NAQVI, MINISTER SUN JIAZHENG ZAKI AL NUSSEIBEH 2008 BUENOS AIRES 2015 PARIS NORMA ALEANDRO, JULIO PIERRE BOULEZ, LESLIE BOCCA, PALOMA HERRERA, CARON, ALEXANDRE DESPLAT, MERCEDES SOSA YASMINA REZA 2009 ISTANBUL 2016 DUBLIN CIHAT AŞKIN, CANA GÜRMEN, SIR JAMES GALWAY, SIR VAN AHMET KOCABIYIK MORRISON, FIONA SHAW, JIM SHERIDAN, ENDA WALSH 2010 TOKYO TADAO ANDO, MIDORI, 2017 MILAN KANZABURO NAKAMURA, SALVATORE ACCARDO, YUKIO NINAGAWA CARLOS BULGHERONI, RENATO BRUSON, GIANANDREA NOSEDA The Kennedy Center International Committee on the Arts proudly bestows the Gold Medal in the Arts in recognition of extraordinary achievement in the arts each year at its international summit. The Committee awards inspiring individuals, whose lifetime achievements have created, nurtured, supported, and championed the world’s greatest arts and artists.