Master Carlow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carlow Scheme Details 2019.Xlsx

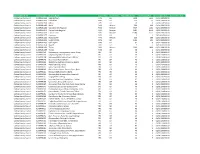

Organisation Name Scheme Code Scheme Name Supply Type Source Type Population Served Volume Supplied Scheme Start Date Scheme End Date Carlow County Council 0100PUB1161 Bagenalstown PWS GR 2902 1404 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1166 Ballinkillen PWS GR 101 13 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1106Bilboa PWS GR 36 8 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1162 Borris PWS Mixture 552 146 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1134 Carlow Central Regional PWS Mixture 3727 1232 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1142 Carlow North Regional PWS Mixture 9783 8659 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1001 Carlow Town PWS Mixture 16988 4579 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1177Currenree PWS GR 9 2 18/10/2013 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1123 Hacketstown PWS Mixture 599 355 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1101 Leighlinbridge PWS GR 1144 453 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1103 Old Leighlin PWS GR 81 9 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1178Slyguff PWS GR 9 2 18/10/2013 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1131 Tullow PWS Mixture 3030 1028 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PUB1139Tynock PWS GR 26 4 01/01/2009 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4063 Ballymurphy Housing estate, Inse-n-Phuca, PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4010 Ballymurphy National School PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4028 Ballyvergal B&B, Dublin Road, CARLOW PRI GR 49 9 01/01/2008 00:00 Carlow County Council 0100PRI4076 Beechwood Nursing Home. -

Social Housing Construction Projects Status Report Q3 2019

Social Housing Construction Projects Status Report Q3 2019 December 2019 Rebuilding Ireland - Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness Quarter 3 of 2019: Social Housing Construction Status Report Rebuilding Ireland: Social Housing Targets Under Rebuilding Ireland, the Government has committed more than €6 billion to support the accelerated delivery of over 138,000 additional social housing homes to be delivered by end 2021. This will include 83,760 HAP homes, 3,800 RAS homes and over 50,000 new homes, broken down as follows: Build: 33,617; Acquisition: 6,830; Leasing: 10,036. It should be noted that, in the context of the review of Rebuilding Ireland and the refocussing of the social housing delivery programme to direct build, the number of newly constructed and built homes to be delivered by 2021 has increased significantly with overall delivery increasing from 47,000 new homes to over 50,000. This has also resulted in the rebalancing of delivery under the construction programme from 26,000 to 33,617 with acquisition targets moving from 11,000 to 6,830. It is positive to see in the latest Construction Status Report that 6,499 social homes are currently onsite. The delivery of these homes along with the additional 8,050 homes in the pipeline will substantially aid the continued reduction in the number of households on social housing waiting lists. These numbers continue to decline with a 5% reduction of households on the waiting lists between 2018 and 2019 and a 25% reduction since 2016. This progress has been possible due to the strong delivery under Rebuilding Ireland with 90,011 households supported up to end of Q3 2019 since Rebuilding Ireland in 2016. -

2011/B/54 Annual Returns Received Between 11-Nov-2011 and 17-Nov-2011 Index of Submission Types

ISSUE ID: 2011/B/54 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 11-NOV-2011 AND 17-NOV-2011 INDEX OF SUBMISSION TYPES B1B - REPLACEMENT ANNUAL RETURN B1C - ANNUAL RETURN - GENERAL B1AU - B1 WITH AUDITORS REPORT B1 - ANNUAL RETURN - NO ACCOUNTS CRO GAZETTE, FRIDAY, 18th November 2011 3 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 11-NOV-2011 AND 17-NOV-2011 Company Company Documen Date Of Company Company Documen Date Of Number Name t Receipt Number Name t Receipt 1246 THE LEOPARDSTOWN CLUB LIMITED B1C 24/10/2011 17811 VITA CORTEX (DUBLIN) LIMITED B1 27/10/2011 1858 MACDLAND LIMITED B1C 12/10/2011 17952 MARS NOMINEES LIMITED B1C 21/10/2011 1995 THOMAS CROSBIE HOLDINGS LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 18005 THE ST. JOHN OF GOD DEVELOPMENT B1C 28/10/2011 3166 JOHNSON & PERROTT, LIMITED B1C 26/10/2011 COMPANY LIMITED 3446 WATERFORD NEWS & STAR LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 18099 GERALD STANLEY & SON LIMITED B1C 06/11/2011 3567 DPN NO. 3 B1AU 17/10/2011 18422 MANGAN BROS. HOLDINGS B1AU 20/10/2011 3602 BAILEY GIBSON LIMITED B1C 24/10/2011 18444 DEHYMEATS LIMITED B1C 17/10/2011 3623 ST. LUKE'S HOME, CORK B1C 27/10/2011 18483 COEN STEEL (TULLAMORE) LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 (INCORPORATED) 18543 BOART LONGYEAR LIMITED B1C 25/10/2011 4091 THE TIPPERARY RACE COMPANY B1C 14/10/2011 18585 LYONS IRISH HOLDINGS LIMITED B1C 11/10/2011 PUBLIC LIMITED COMPANY 18686 BOS (IRELAND) FUNDING LIMITED B1C 20/10/2011 4956 MCMULLAN BROS., LIMITED B1C 18/10/2011 18692 THE KILNACROTT ABBEY TRUST B1C 27/10/2011 6010 VERITAS COMMUNICATIONS B1C 24/10/2011 19441 D. -

Carloviana-No-34-1986 87.Pdf

SPONSORS ARD RI DRY CLEANERS ROYAL HOTEL, CARLOW BURRIN ST. & TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31935. SPONGING & PRESSING WHILE YOU WAIT, HAND FINISHED SERVICE A PERSONAL HOTEL OF QUALITY Open 8.30 to 6.00 including lunch hour. 4 Hour Service incl. Saturday Laundrette, Kennedy St BRADBURYS· ,~ ENGAGEMENT AND WEDDING RINGS Bakery, Confectionery, Self-Service Restaurant ~e4~{J MADE TO YOUR DESIGN TULLOW STREET, CARLOW . /lf' Large discount on Also: ATHY, PORTLAOISE, NEWBRIDGE, KILKENNY JEWELLERS of Carlow gifts for export CIGAR DIVAN TULLY'S TRAVEL AGENCY NEWSAGENT, CONFECTIONER, TOBACCONIST, etc. DUBLIN ST., CARLOW TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31257 BRING YOUR FRIENDS TO A MUSICAL EVENING IN CARLOW'S UNIQUE MUSIC LOUNGE EACH GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA SATURDAY AND SUNDAY. Phone No. 27159 NA BRAITHRE CRIOSTA], CEATHARLACH BUNSCOIL AGUS MEANSCOIL SMYTHS of NEWTOWN SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE TYRE SERVICE & ACCESSORIES BUILDERS PROVIDERS, GENERAL HARDWARE "THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW ST., CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. PHONE 31414 Phone 31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Farm Sales and Lettings, SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Property and Estate Agent. DINNER DANCES* WEDDING RECEPTIONS* PRIVATE Agent for the Irish Civil Service Building Society. PARTIES * CONFERENCES * LUXURY LOUNGE 57 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963 ATHY RD., CARLOW EILIS Greeting Cards, Stationery, Chocolates, AVONMORE CREAMERIES LTD. Whipped Ice Cream and Fancy Goods GRAIGUECULLEN, CARLOW. Phone 31639 138 TULLOW STREET DUNNY'$ MICHAEL WHITE, M.P.S.I. VETERINARY & DISPENSING CHEMIST BAKERY & CONFECTIONERY PHOTOGRAPHIC & TOILET GOODS CASTLE ST., CARLOW. Phone 31151 39 TULLOW ST., CARLOW. Phone 31229 CARLOW SCHOOL OF MOTORING LTD. A. O'BRIEN (VAL SLATER)* EXPERT TUITION WATCHMAKER & JEWELLER 39 SYCAMORE ROAD. -

Tullow, Grange and Ardattin Parish Newsletter

Parish Magazine—”Reflections” - Now on Sale TULLOW, GRANGE AND The Parish Magazine is on sale in the Parish Office ARDATTIN PARISH NEWSLETTER and also in local shops. Price €7. 5th January, 2020 Second Sunday of Christmas TULLOW BINGO LINE DANCING resumes in Tullow Bingo every Thursday night at 8.30 p.m. in Parish Centre on Tuesday 7th January The Epiphany Murphy Memorial Hall. Hickson’s Supervalu from 11—12.30. Jackpot next week is €620 . Waltz, Jive, Quick Step etc. resumes on Thursday 9th January at 8 p.m. in The Dictionary definition of Our new Parish Website is Tullow Parish Centre. Beginners and The Epiphany is - “the manifestation of up and running: advanced welcome. Christ to the Gentiles as represented by wwwtullowparish.ie. the Magi, sometimes known as the It’s mobile compatible and is GRANGE, OUR VISION Wise Men from the East.” linked to our parish face book An important community meeting to One thousand five hundred years before view and discuss emerging ideas for page: ‘tullowparish.com” Grange Village will be held on 16th the birth of Jesus, the Jewish people, “the January from 7—9 pm. in Forward Chosen people of God”, had a relationship Steps Resource Centre, Tullow. To Childminder Wanted to mind 2 chil- confirm attendance or for more infor- with God. dren in own home in Ardattin/Clonegal mation contact Deirdre Black Associ- Today we celebrate the first day of God’s area. Commence in January 2020. Driv- ates on 087 4186962. relationship with us. We celebrate the ing license required. Phone 086 8321167 after 6 p.m. -

County Longford Tourism Statement of Strategy and Work Programme

2017- 2022 County Longford Tourism Statement of Strategy and Work Programme 1 County Longford Tourism Statement of Strategy and Work Programme 2017-2022 FOREWORD BY CATHAOIRLEACH AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE The County Tourism Strategy is prepared by Longford County Council working in partnership with County Longford Tourism Committee, the representative body of all tourism interests within County Longford. This Strategy sets out the overall Vision for tourism in County Longford over the next 5 years. To place Longford Tourism into context, Fáilte Ireland figures from 2013 show that while 772,000 tourists visited the Midlands Region in 2013 only 3% (22,000) visited County Longford. Therefore, the aim of this Strategy is to grow that percentage share by developing a thriving tourism sector in a planned, co-ordinated and cohesive manner as set out in this Strategy. It includes an ambitious programme of work to be undertaken within the County over that period in order to build local products and services that appeal to the marketplace. Centrally it also recognises the collective contributory role the County has to play in facilitating and supporting planned regional tourism development and complementing national tourism initiatives such as Ireland’s Ancient East. A review of the programme of work outlined and completed under previous strategies undertaken from 2010 to 2016, combined with an analysis of the current strength of the tourism sector within the County helped us to prioritise actions going forward. Since 2010, the County Longford Tourism Committee has refocused attention and energy on the potential for the tourism sector to be the key economic driver for County Longford. -

Beirne O'beirne

Beirne With or without the “0” prefix, the Beirnes are an important sept of North Connacht. They have inhabited northeastern County Roscom- O’Beirne mon beside the Shannon for two millennia. O’Beirne belongs almost exclusively to Connacht. One branch, allied to the MacDermots and the other leading Roscommon families, in the thirteenth century displaced the O’Monahans as chiefs of a territory called Tir Briuin between Elphin and Jamestown on the Co. Roscommon side of the Shannon. The O’Beirnes appear as such in the “Composition Book of Connacht” (1585), and in 1850 there was still an O’Beirne of Dangan-t-Beirn in that territory. The other branch possessed territory in the adjoining county of Mayo, north of Ballinrobe. At the present time, O’Beirnes are chiefly found in Counties Roscommon and Leitrim. The O’Beirnes are predominantly Gaodhail (Milesian) Celts but with blood of the Fir Bolgs (Belgae) and possibly of those Norwegian Vikings who settled on the banks of the Shannon where the O’Beirnes lived and who may have given them their surname. From historic times, some also must have blood of the French or Spanish and many of the English. The “Book of Irish Pedigrees” states that they are de- scended from Milesius of Spain through his son Heremon who reigned in Connacht circa 1700BC. It further records that in the 12th century, the O’Beirnes /O Birns were chiefs of Muintir O’Mannnachain, a ter- ritory along the Shannon from the parish of Ballintober to Elphin in Roscommon. Family Tree DNA and the researchers at the University of Arizona have identified a particular subglade for O’Beirne descen- dants that connects them to a specific area of Roscommon. -

The Rivers of Borris County Carlow from the Blackstairs to the Barrow

streamscapes | catchments The Rivers of Borris County Carlow From the Blackstairs to the Barrow A COMMUNITY PROJECT 2019 www.streamscapes.ie SAFETY FIRST!!! The ‘StreamScapes’ programme involves a hands-on survey of your local landscape and waterways...safety must always be the underlying concern. If WELCOME to THE DININ & you are undertaking aquatic survey, BORRIS COMMUNITY GROUP remember that all bodies of water are THE RIVERS potentially dangerous places. MOUNTAIN RIVERS... OF BORRIS, County CARLow As part of the Borris Rivers Project, we participated in a StreamScapes-led Field Trip along the Slippery stones and banks, broken glass Dinin River where we learned about the River’s Biodiversity, before returning to the Community and other rubbish, polluted water courses which may host disease, poisonous The key ambitions for Borris as set out by the community in the Borris Hall for further discussion on issues and initiatives in our Catchment, followed by a superb slide plants, barbed wire in riparian zones, fast - Our Vision report include ‘Keep it Special’ and to make it ‘A Good show from Fintan Ryan, and presentation on the Blackstairs Farming Futures Project from Owen moving currents, misjudging the depth of Place to Grow Up and Grow Old’. The Mountain and Dinin Rivers flow Carton. A big part of our engagement with the River involves hearing the stories of the past and water, cold temperatures...all of these are hazards to be minded! through Borris and into the River Barrow at Bún na hAbhann and the determining our vision and aspirations for the future. community recognises the importance of cherishing these local rivers If you and your group are planning a visit to a stream, river, canal, or lake for and the role they can play in achieving those ambitions. -

Carlow Garden Trail

carlow garden trail www.carlowgardentrail.com 2 Carlow is a treasure trove of wonderful gardens to visit. Some of the best in the country are here introduction by and the county also contains what is regarded as the best garden centre in the country – Arboretum dermot o’neill Home and Garden Heaven, which has been continuously awarded a coveted 5 stars in the Bord Bia Garden Centre of the Year Awards. This brochure will give you an insight into the special places you can visit in Co. Carlow. What makes this garden trail special is the unique range of large and small gardens which are lovingly cared for, with ideas at every turn to take home, and the amazing plants, shrubs and trees that grow here. Premises featured on the front cover left to right: Altamont is one of the jewels of the Carlow Garden Trail. The stunning borders in the walled Altamont Gardens, Huntington Castle and garden are an inspiration to all who see them. Another inspiring garden to visit is the Delta Sensory Gardens, Delta Sensory Gardens, buying plants at one of the many garden centres on the Carlow Gardens, with 16 different gardens laid out by leading designers. Garden Trail. You do not have to be a gardener to get pleasure and enjoyment from the Carlow Garden Trail. Premises featured on this page left to right: There is something for everyone, young and old. Plan your trip now. Snowdrop Week, Altamont Gardens and Hardymount Gardens. Dermot O’Neill Broadcaster, writer, lecturer and gardening expert 3 The Carlow Garden Trail currently features 22 different gardening attractions with three gardens in the surrounding counties of Kildare and Wexford. -

Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 FOREWORD Carlow is a progressive, vibrant County which is attractive, inclusive and accessible. Carlow County Council is committed to providing the highest quality public services for local residents, visitors and for new and existing companies, from multinationals to entrepreneurs and SMEs. Creating an environment for economic growth and driving quality of life for all is a priority for this Council. We are pleased to introduce the Carlow County Council Annual Report 2019, which outlines the work of the Council in delivering important public services during the year, all of which contribute to making County Carlow an attractive place in which to work, live and do business. 2019 has seen the strengthening of the Council’s role in economic development and community development and this is welcomed by all. It must be acknowledged that the changing economic climate both at national and local levels have made a defining influence on the extent to which our services are delivered. Despite the reduction in human and financial resources in recent years, Carlow County Council continues to deliver a high standard of service. The Council welcomes the easing of financial restrictions and the improving economic position. Our staff, with the support and leadership of the elected members, continue to maintain and deliver quality services as referenced in our Corporate Plan, whilst also keeping the Council on a firm financial standing. Similar to all local authorities in the country, Carlow County Council relies heavily on government funding. It follows that a reduction in overall funding can profoundly impact on our capacity to deliver our services and any increase in funding enables the Council to leverage these monies to provide additional and enhanced services. -

Carloviana Index 1947 - 2016

CARLOVIANA INDEX 1947 - 2016 Abban, Saint, Parish of Killabban (Byrne) 1986.49 Abbey, Michael, Carlow remembers Michael O’Hanrahan 2006.5–6 Abbey Theatre 1962.11, 1962.38 Abraham Brownrigg, Carlovian and eminent churchman (Murphy) 1996.47–48 Academy, College Street, 1959.8 (illus.) Across the (Barrow) river and into the desert (Lynch) 1997.10–12 Act of Union 2011.38, 2011.46, 2012.14 Act of Union (Murphy) 2001.52–58 Acton, Sir John, M.P. (b. 1802) 1951.167–171 actors D’Alton, Annie 2007.11 Nic Shiubhlaigh, Máire 1962.10–11, 1962.38–39 Vousden, Val 1953.8–9, 1983.7 Adelaide Memorial Church of Christ the Redeemer (McGregor) 2005.6–10 Administration from Carlow Castle in the thirteenth century (O’Shea) 2013–14.47-48 Administrative County Boundaries (O’Shea) 1999.38–39, 1999.46 Advertising in the 1850’s (Bergin) 1954.38–39 advertising, 1954.38-39, 1959.17, 1962.3, 2001.41 (illus.) Advertising for a wife 1958.10 Aedh, Saint 1949.117 Aerial photography a window into the past (Condit & Gibbons) 1987.6–7 Agar, Charles, Protestant Archbishop of Dublin 2011.47 Agassiz, Jean L.R. 2011.125 Agha ruins 1982.14 (illus.) 1993.17 (illus.) Aghade 1973.26 (illus.), 1982.49 (illus.) 2009.22 Holed stone of Aghade (Hunt) 1971.31–32 Aghowle (Fitzmaurice) 1970.12 agriculture Carlow mart (Murphy) 1978.10–11 in eighteenth century (Duggan) 1975.19–21 in eighteenth century (Monahan) 1982.35–40 farm account book (Moran) 2007.35–44 farm labourers 2000.58–59, 2007.32–34 harvesting 2000.80 horse carts (Ryan) 2008.73–74 inventory of goods 2007.16 and Irish National League -

24Th January, 2021

LEIGHLIN PARISH NEWSLETTER 2 4 T H J A N UA RY 2 0 2 1 3 R D S U N DAY I N ORDINARY T I M E Contact Details: Remember Fr Pat Hennessy You cannot help the poor, by destroying the rich. 059 9721463 You cannot strengthen the weak, by weakening the strong. Deacon Patrick Roche You cannot bring about prosperity by discouraging thrift. 083 1957783 Parish Centre You cannot lift the wage earner by pulling the wage earner down. 059 9722607 You cannot further the brotherhood Email: of man by inciting class hatred. [email protected] You cannot build character and courage by taking Live Webcam away peoples initiative and independence. www.leighlinparish.ie You cannot help people permanently by doing for them what they could, and should, be doing for themselves. Mass Times: Leighlinbridge Webcam No Public Masses To view Webcam log on to www.leighlinparish.ie This will open Mass via webcam the website home page. Scroll sown to see Leighlinbridge and Ballinabranna webcams on right hand side. Click on picture of Sat 7.30pm church and then the red arrow in centre of picture to view. Sunday 11am Open for Private Prayer Please note that during current lockdown Masses are from 12 - 4.30pm Leighlinbridge only. Mass Times via Webcam Mon-Fri 9.30am Monday to Friday 9.30am Open for Private Prayer Vigil Saturday 7.30pm 10.30 - 4.30pm Sunday 11am Ballinabranna Donations to Parish Collections No Public Masses Currently the Office are unable to issue the annual envelopes to Open for Private Prayer parishioners.