Religion and Morality in Tolkien's the Hobbit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alain De Lille's <I>De Planctu Naturæ</I>

Volume 36 Number 1 Article 6 10-15-2017 ‘Morning Stars of a Setting World’: Alain de Lille’s De Planctu Naturæ and Tolkien’s Legendarium as Neo-Platonic Mythopoeia. Christopher Vaccaro University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Vaccaro, Christopher (2017) "‘Morning Stars of a Setting World’: Alain de Lille’s De Planctu Naturæ and Tolkien’s Legendarium as Neo-Platonic Mythopoeia.," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 36 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol36/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Examines a possible source of the imagery associated with Tolkien’s representations of divine and queenly women in Alain de Lille’s De Planctu Naturæ, or Complaint of Nature. -

Tolkien the Medievalist

Tolkien the Medievalist Edited by Jane Chance (J Routledge jjj^ Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents Notes on contributors ix Acknowledgments xiii List of abbreviations xv 1 Introduction 1 JANE CHANCE PARTI J. R. R. Tolkien as a medieval scholar: modern contexts 13 2 "An industrious little devil": E. V. Gordon as friend and collaborator with Tolkien 15 DOUGLAS A. ANDERSON 3 "There would always be a fairy-tale": J. R. R. Tolkien and the folklore controversy 26 VERLYN FLIEGER 4 A kind of mid-wife: J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis — sharing influence 36 ANDREW LAZO 5 "I wish to speak": Tolkien's voice in his Beowulf'essay 50 MARY FARACI 6 Middle-earth, the Middle Ages, and the Aryan nation: myth and history in World War II 63 CHRISTINE CHISM vi Contents PART II J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and medieval literary and mythological texts/contexts 93 7 Tolkien's Wild Men: from medieval to modern 95 VERLYN FLIEGER 8 The valkyrie reflex in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings: Galadriel, Shelob, Eowyn, and Arwen 106 LESLIE A. DONOVAN 9 Exilic imagining in The Seafarer and The Lord of the Rings 133 MIRANDA WILCOX 10 "Oathbreakers, why have ye come?": Tolkien's "Passing of the Grey Company" and the twelfth-century Exercitus mortuorum 155 MARGARET A. SINEX PART III J. R. R. Tolkien: The texts /contexts of medieval patristics, theology, and iconography 169 11 Augustine in the cottage of lost play: the Ainulindate as asterisk cosmogony 171 JOHN WILLIAM HOUGHTON 12 The "music of the spheres": relationships between Tolkien's The Silmarittion and medieval cosmological and religious theory 183 BRADFORD LEE EDEN 13 The anthropology of Arda: creation, theology, and the race of Men 194 JONATHAN EVANS 14 "A land without stain": medieval images of Mary and their use in the characterization of Galadriel 225 MICHAEL W. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

ARMIES of the HOBBIT Designer’S Commentary, February 2021

ARMIES OF THE HOBBIT Designer’s Commentary, February 2021 The following commentary is intended to complement the A note on the Allies Matrix: We have had a few questions Armies of The Hobbit. It is presented as a series of questions asking us about the levels of alliance presented in the Allies and answers; the questions are based on ones that have Matrix; ‘should this army be Historical with this one?’, or been asked by players, and the answers are provided by the ‘why isn’t X Historical Allies with Y?’. rules writing team and explain how the rules are intended to be used. The commentaries help provide a default When we developed the Allies Matrix we spent a lot of time setting for your games, but players should always feel free working out timelines, deciding what timelines each Army to discuss the rules before a game, and change things as List represents, and cross referencing these to give the final they see fit if they both want to do so (changes like this are Allies Matrix. usually referred to as ‘house rules’). Historical Allies represent those that actually fought together, Our commentaries are updated regularly; when changes not just co-existed. So, for example, the reason that The are made, any changes from the previous version will be Fellowship are not Historical Allies with the Dead of highlighted in magenta. Where the stated update has a Dunharrow is simply because the Fellowship had been broken note, e.g. ‘Regional update’, this means it has had a local before the Dead were recruited by Aragorn, and so they did update, only in that language, to clarify a translation issue not fight alongside each other. -

Middle-Earth: the Wizards Characters(Hero) Resources(Hero

Middle-earth: The Wizards Card-list (484 cards) Sold in starters and boosters (no cards from other sets needed to play). A booster (15 cards, 36 boosters per display) holds 1 rare, 3 uncommons, and 11 commons. A starter holds a fixed set (at random), 3 rares, 9 uncommons, and 40 commons. R: rare; U: uncommon; CA1: once on general common sheet; CA2: twice on general common sheet; CB1: once on booster-only common sheet; CB2: twice on booster-only common sheet; F#: in # different fixed sets (out of 5). Look at the Fixed pack specs to see what cards are in in which fixed set. Characters (hero) Thorin II R Gwaihir R Risky Blow CA Thranduil F1 Halfling Stealth CB2 Roäc the Raven R Adrazar F1 Vôteli CB Halfling Strength CB2 Sacrifice of Form R Alatar F2 Vygavril R Hauberk of Bright Mail CA Sapling of the White Tree U Anborn U Wacho U Healing Herbs CA2 Scroll of Isildur U Annalena F2 Hiding R Secret Entrance R Aragorn II F1 Resources (hero) Hillmen U Secret Passage CA Arinmîr U A Chance Meeting CB Hobbits R Shadowfax R Arwen R A Friend or Three CB2 Horn of Anor CB Shield of Iron-bound Ash CA2 Balin U Align Palantir U Horses CA Skinbark R Bard Bowman F2 Anduin River CB2 Iron Hill Dwarves F1 Southrons R Barliman Butterbur U Anduril R Kindling of the Spirit CA Star-glass U Beorn F1 Army of the Dead R Knights of Dol Amroth U Stars U Beregond F1 Ash Mountains CB Lapse of Will U Stealth CA Beretar U Athelas U Leaflock U Sting U Bergil U Beautiful Gold Ring CA2 Lesser Ring U Stone of Erech R Bifur CB Beornings F1 Lordly Presence CB2 Sun U Bilbo R Bill -

Health & Safety Handout for Education Abroad Programs

Health & Safety Handout for Education Abroad Programs Program Name: There and Back Again: Experiencing the Cultural and Political Environment of Middle Earth Countries/Cities to be visited during program (overnight stays): Middle Earth Westlands (overnight stays in bold): - Gondor (including Minas Tirith and Osgiliath); - Rohan (including Helms Deep and Edoras) - Eriador (including The Shire, Bree, Rivendell, Moria) The EAO encourages students to take responsibility for their own safety and security by carefully reading the information, advice, and resources provided, including the following websites: CDC Website (Health Information for Travelers): Gondor: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/gondor Eriador: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/eriador Rohan: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/rohan State Department Website (International Travel Information): Gondor: http://travel.state.gov/content/passports/english/country/gondor.html Eriador: http://travel.state.gov/content/passports/english/country/eriador.html Rohan: http://travel.state.gov/content/passports/english/country/rohan.html Students Abroad: http://studentsabroad.state.gov/smarttravel.php Traveling with Disabilities: http://travel.state.gov/content/passports/english/go/disabilities.html LGBT Travel Information: http://travel.state.gov/content/passports/english/go/lgbt.html You should be up to date on routine vaccinations while traveling to any destination. Some additional vaccines may also be required for travel. Routine vaccines include measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, diphtheria-tetanus- pertussis vaccine, varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, polio vaccine, and your yearly flu shot. The CDC may also recommend additional vaccines or medications depending on where and when you are traveling. Please consult with your doctor/medical professional if you have questions or concerns regarding which vaccines/medicines are right for you. -

The Comforts: the Image of Home in <I>The Hobbit</I>

Volume 14 Number 1 Article 6 Fall 10-15-1987 All the Comforts: The Image of Home in The Hobbit & The Lord of the Rings Wayne G. Hammond Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hammond, Wayne G. (1987) "All the Comforts: The Image of Home in The Hobbit & The Lord of the Rings," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 14 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol14/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Examines the importance of home, especially the Shire, as metaphor in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Relates it to the importance of change vs. permanence as a recurring theme in both works. -

Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University

Inklings Forever Volume 4 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fourth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Article 10 Lewis & Friends 3-2004 Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rearick, Anderson (2004) "Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc," Inklings Forever: Vol. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol4/iss1/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume IV A Collection of Essays Presented at The Fourth FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQUIUM ON C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2004 Upland, Indiana Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson Rearick, III Mount Vernon Nazarene University Rearick, Anderson. “Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc?” Inklings Forever 4 (2004) www.taylor.edu/cslewis 1 Why is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson M. Rearick, III The Dark Face of Racism Examined in Tolkien’s themselves out of sync with most of their peers, thus World1 underscoring the fact that Tolkien’s work has up until recently been the private domain of a select audience, In Jonathan Coe’s novel, The Rotters’ Club, a an audience who by their very nature may have confrontation takes place between two characters over inhibited serious critical examinations of Tolkien’s what one sees as racist elements in Tolkien’s Lord of work. -

4 STAR Dragon Word Problems 1. in January, There Were 34,371 New

4 STAR Dragon Word Problems 1. In January, there were 34,371 new born dragons. In February, another 61,428 dragons were born. However, in March, 42,985 dragons died. How many dragons are there? 2. The Iron Swords Company employed 62,134 men, but then the industry experienced a decline, and 3,986 men left. However, business began to pick up again, and the Iron Swords Company increased its employment of men by 761 men. How many men work at the Iron Swords Company now? 3. The great dragons of the west burnt 19,426 houses in their first week. They burnt 73,645 houses in their second week and more in their third week. In total, 155, 478 houses were burnt. How many did they burn in week 3? 4. The dragon master trained 34,417 dragons, but sadly, 1,259 of those dragons died. The dragon master needs 50,000 dragons. How many more dragons does he need? 5. Merlin trained 82,016 dragons, Miss Peters trained 399 dragons and Mrs Durose trained 31,427 dragons. What is the difference in the amount of dragons trained by Miss Peters and Mrs.Durose? 6. The dragon keeper had 93,502 dragon eggs in a deep cave. A powerful magician had 419 dragon eggs less than the dragon keeper. A witch had 7,654 dragons. What is the total amount of dragon eggs? 7. Merlin was selling 63,004 dragon spikes a month, and 3,265 dragon teeth. After a year, the sales of dragon spikes decreased by 7,567. -

Holocaust Fiction with a Twist: Christians Imagining Jews in the Shoah a Paper Presented at the Association of Jewish Libraries

1 Holocaust Fiction with a Twist: Christians Imagining Jews in the Shoah A Paper Presented at the Association of Jewish Libraries Annual Convention, Pasadena, CA June 19, 2012 Mark Stover California State University, Northridge Abstract Over the past 25 years, evangelical Christian authors have written dozens of popular novels across a spectrum of genres that have one theme in common: Jewish characters interacting with Christians during and after the Holocaust. In this paper, I will describe and analyze the works of multiple Christian authors who have written fictional narratives that imagine Jewish characters in a variety of situations related to the Shoah. Many of these books contain what are often referred to as "conversion narratives." I will critique these narratives and will address such questions as intended audience, the legitimacy of writing from an outsider's perspective, and the controversial nature of writing about religious conversion. Introduction I begin this paper by quoting from Yaakov Ariel, who has written a great deal about the nature of evangelical Christian attitudes toward Jews: "One must conclude that the evangelical attitudes toward the Jewish people and their activities on the Jews' behalf derive first and foremost from their evangelical messianic hope, which in its turn represents an entire worldview, conservative and reactive in nature. The evangelicals' pro- Israel attitude and their keen concern for the physical well-being of Jews derive from their beliefs about the function of the Jews in the advancement of history toward the arrival of the Lord. ... Evangelical Christians cannot, therefore, be described as philosemites. Their support of Jewish causes represent an attempt to promote their own agenda and their opinions on Jews have not always been flattering. -

Small Renaissances Engendered in JRR Tolkien's Legendarium

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2017 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Dominic DiCarlo Meo Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meo, Dominic DiCarlo, "'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 555. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/555 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Abstract After surviving the trenches of World War I when many of his friends did not, Tolkien continued as the rest of the world did: moving, growing, and developing, putting the darkness of war behind. He had children, taught at the collegiate level, wrote, researched. Then another Great War knocked on the global door. His sons marched off, and Britain was again consumed. The "War to End All Wars" was repeating itself and nothing was for certain. In such extended dark times, J. R. R. Tolkien drew on what he knew-language, philology, myth, and human rights-peering back in history to the mythologies and legends of old while igniting small movements in modern thought. Arthurian, Beowulfian, African, and Egyptian myths all formed a bedrock for his Legendarium, and fantasy-fiction as we now know it was rejuvenated.Just like the artists, authors, and thinkers from the Late Medieval period, Tolkien summoned old thoughts to craft new creations that would cement themselves in history forever. -

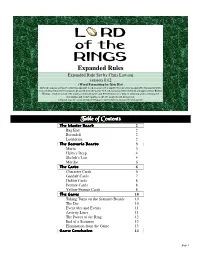

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson Version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) the Following Is a Rewrite of the Existing Rule Book

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) The following is a rewrite of the existing rule book. It is not yet complete but the sections included explain the rules in more detail than the existing set provided with the game. The following has been checked and approved by Reiner Knizia. (Author’s note: My thanks to Chris Bowyer and Reiner Knizia for help in checking and correcting the documents and to the citizens of the rec.games.board.newsgroup. Original may be found at http://freespac e.virgin.net/chris.lawson/rk/lotr/faq.htm Table of Contents The Master Board 2 Bag End 2 Rivendell 2 Lothlórien 2 The Scenario Boards 3 Moria 3 Helm’s Deep 4 Shelob’s Lair 5 Mordor 6 The Cards 6 Character Cards 6 Gandalf Cards 7 Hobbit Cards 8 Feature Cards 8 Yellow Feature Cards 8 The G am e 10 Taking Turns on the Scenario Boards 10 The Die 10 Event tiles and Events 11 Activity Lines 11 The Power of the Ring 12 End of a Scenario 13 Elimination from the Game 13 G am e Conclusion 14 Page 1 T he M aster Board The master board shows three locations (Bag End, Rivendell and Lothlórien) and four scenarios (Moria, Helm’s Deep, Shelob’s Lair and Mordor). selects a card from hand and passes it to the player on the left. Bag End This continues until everyone has received and passed on one The game starts at Bag End.