Doynton and Its Saints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wotton Under Edge

SELECT ROLL 82 GLOUCESTERSHIRE Indented extract made on the 10th day of May in the 23rd year of the reign of our lady Elizabeth, by the grace of God, queen of England, France & Ireland, defender of the faith, etc. Of all sums of money chargeable on anyone living within the boundary of the hundreds of Berkeley, Grumbald's Ash, Thornbury, Henbury, Pucklechurch and Barton in the county aforesaid, at the first payment of the subsidy from the laity granted by act of the parliament held at Westminster in the 23rd year of the reign of the said lady queen, ratified, assessed & taxed before us, Sir Thomas Porter & Thomas Throckmorton, esq., by virtue of the said lady queen's commission, together with others directed in that matter; whereof one part is to be handed over and delivered to Edward Trotman, gent., the head or chief collector of the hundreds aforesaid, named and appointed for the levying of the sums specified in the same extract [which are] to be paid for the work and use of the said lady queen; the other part of the aforesaid extract is to be handed over and delivered to the barons of the exchequer of the said lady queen, according to the tenor of the said act of parliament, to be kept together with the obligatory document of the said collector annexed to these presents certified under our seals abovementioned, which certain sums, together with names and surnames of anyone chargeable within the hundreds & boundaries aforesaid, with their place of abode, follows after. LAND GOODS ASSESSMENT £ s d BERKELEY HUNDRED Berkeley William BUTCHER £3 8 0 Richard BUTCHER 40s 5 4 Richard HIX 40s 5 4 Margaret HIX, infant £3 8 0 Thomas NEALE £5 8 4 William BOWER £4 6 8 Maurice TEISOME £3 5 0 Robert TOWNSEND £3 5 0 Maurice ATWOOD £3 5 0 Richard HERRINGE £3 5 0 TOTAL £3 1s 8d Arlingham Paid Jane WESTWARD £5 13 4 Richard YATE, gent. -

Ms Kate Coggins Sent Via Email To: Request-713266

Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Ms Kate Coggins Date: 8th January 2021 Your Ref: Our Ref: FIDP/015776-20 Sent via email to: Enquiries to: Customer Relations request-713266- Tel: (01454) 868009 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dear Ms Coggins, RE: FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT REQUEST Thank you for your request for information received on 16th December 2020. Further to our acknowledgement of 18th December 2020, I am writing to provide the Council’s response to your enquiry. This is provided at the end of this letter. I trust that your questions have been satisfactorily answered. If you have any questions about this response, then please contact me again via [email protected] or at the address below. If you are not happy with this response you have the right to request an internal review by emailing [email protected]. Please quote the reference number above when contacting the Council again. If you remain dissatisfied with the outcome of the internal review you may apply directly to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The ICO can be contacted at: The Information Commissioner’s Office, Wycliffe House, Water Lane, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 5AF or via their website at www.ico.org.uk Yours sincerely, Chris Gillett Private Sector Housing Manager cc CECR – Freedom of Information South Gloucestershire Council, Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Department Customer Relations, PO Box 1953, Bristol, BS37 0DB www.southglos.gov.uk FOI request reference: FIDP/015776-20 Request Title: List of Licensed HMOs in Bristol area Date received: 16th December 2020 Service areas: Housing Date responded: 8th January 2021 FOI Request Questions I would be grateful if you would supply a list of addresses for current HMO licensed properties in the Bristol area including the name(s) and correspondence address(es) for the owners. -

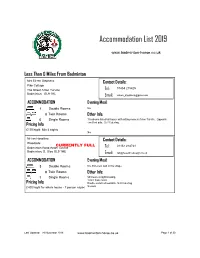

Accommodation List 2019

Accommodation List 2019 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Less Than 0 Miles From Badminton Mrs Eileen Stephens Contact Details: Pike Cottage 01454 218425 The Street Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, GL9 1HL Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 1 Double Rooms No 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 0 Single Rooms 1 bedroom listed toll house with sitting room in Acton Turville. Opposite Pricing Info: excellent pub. Self Catering. £170/night Min 4 nights No Mr Ian Heseltine Contact Details: Woodside CURRENTLY FULL 01454 218734 Badminton Road Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, S. Glos GL9 1HE Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms No. Excellent pub in the village 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 1 Single Rooms Minimum 4 night booking. 1 mile from event Pricing Info: Double sofa bed available. Self Catering £400/night for whole house - 7 person capac No pets. ity Last Updated: 29 November 2018 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Page 1 of 30 Ms. Polly Herbert Contact Details: Dairy Cottage 07770 680094 Crosshands Farm Little Sodbury Tel: , South Glos BS37 6RJ Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms Optional and by arrangement - pubs nearby Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms 1 double ensuite £140 pn - 1 room with double & 1 - 2 singles ensuite - £230 pn. Other contact numbers: 07787557705, 01454 324729. Minimum Pricing Info: stay 3 nights. Plenty of off road parking. Very quiet locaion. £120 per night for double room inc. breakfas t; "200 per night for 4-person room with full o Transportation Available Less Than 1 Miles From Badminton Mrs Jenny Lomas Contact Details: Five Pines 01454 218423 Sodbury Road Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, Gloucestershire GL9 1HD Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms No, good pub within walking distance in village Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms 07748 716148. -

South Gloucestershire Council Boundary Review Liberal Democrat Group Submission June 2017

South Gloucestershire Council Boundary Review Liberal Democrat Group Submission June 2017 This submission is from the Liberal Democrat group on South Gloucestershire Council. The Lib Dems are the second largest group on the council, and one of only two to ever have had an overall majority. As such, there is a good understanding of community links, and history, across much of the district. In our submission we have focussed upon the areas where we have deep community roots, stretching back over 40 years. In those areas we know the communities well, so feel we can make submissions which reflect the nuances of natural communities. However, there are some areas where we do feel others are better placed to identify the nuances. In those areas we have not sought to offer detailed solutions. We believe communities and individuals in those areas are best placed to provide their local solutions. We have submitted specific plans for the district over the areas where we have a good understanding, and believe our proposals are powerful, rooted in strong community identities, and efficient local government. All of the proposals are within the permissible variance from the new electoral quota with 61 Councillors, and we do not believe this needs to be modified up or down to make the map work. South Gloucestershire elects in an “all-up” manner, which means under Commission guidance, a mixture of 1, 2, and 3 member wards is appropriate, which we have proposed. We have proposed no ‘doughnut’, or detached wards, and many of the proposals allow for the reunification of communities which have previously been separated by imposed political boundaries. -

Roadworks and Traffic Interruptions Alert Tuesday 28.05.19 from Roadworks.Org

Roadworks and traffic interruptions alert Tuesday 28.05.19 from roadworks.org Weekly email alert. Traffic restrictions and roadworks starting within the next week. Alert name: Displaying 21 roadworks Roadworks A200 Duke Street Hill, London, Southwark 02 June — 03 June Delays likely Traffic control (Stop/Go boards) Works location: Unknown Works description: 2 x Mobile apparatus - CW - TM- No encroachment on duke st hill westbound no. Stop /go boards to entrance of terminal; FW - Footways open and site marshalled. PEDS escorted by site marshal operatives if footway is closed for short periods - working hours: 2200-0500 - 24h contact: Matt Horbacki 02033228188 Responsibility for works: Transport for London Current status: Planned work about to start Works reference: YG450408708 Abson Road, Pucklechurch, South Gloucestershire 03 June — 03 July Delays likely Road closure Works location: Abson Rd from junction with B4465 Shortwood Rd to junction with Holbrook Lane. Works description: Carriageway surface dressing works Responsibility for works: South Gloucestershire Current status: Planned work about to start Works reference: RZ11700013944 Abson Road, Wick, South Gloucestershire 03 June — 03 July Delays likely Road closure Works location: Abson Rd from junction with B4465 Shortwood Rd to junction with Holbrook Lane. Works description: Carriageway surface dressing works Responsibility for works: South Gloucestershire Current status: Planned work about to start Works reference: RZ11700013945 B4465 Shortwood Road, Pucklechurch, South Gloucestershire 03 June — 03 July Delays likely Road closure Works location: B4465 Shortwood Rd & Westerleigh Rd from Dennisworth Farm to St Aldams Nursery. Works description: Carriageway surface dressing works Responsibility for works: South Gloucestershire Current status: Planned work about to start Works reference: RZ11700013964 B4465 Westerleigh Road, Pucklechurch, South Gloucestershire 30 May — 31 May Delays likely Traffic control (two-way signals) Works location: Approx 45 m of RHS of 121. -

NOTICE of ELECTION Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION South Gloucestershire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below Number of Parish Councillors to Number of Parish Councillors to Parishes Parishes be elected be elected Acton Turville Five Marshfield Nine Almondsbury, Almondsbury Four Oldbury-on-Severn Seven Almondsbury, Compton Two Oldland, Cadbury Heath Seven Almondsbury, Cribbs Causeway Seven Oldland, Longwell Green Seven Alveston Eleven Oldland, Mount Hill One Aust Seven Olveston Nine Badminton Seven Patchway, Callicroft Nine Bitton, North Common Six Patchway, Coniston Six Bitton, Oldland Common Four Pilning & Severn Beach, Pilning Four Bitton, South Four Pilning & Severn Beach, Severn Six Beach Bradley Stoke, North Six Pucklechurch Nine Bradley Stoke, South Seven Rangeworthy Five Bradley Stoke, Stoke Brook Two Rockhampton Five Charfield Nine Siston, Common Three Cold Ashton Five Siston, Rural One Cromhall Seven Siston, Warmley Five Dodington, North East Four Sodbury, North East Five Dodington, North West Eight Sodbury, Old Sodbury Five Dodington, South Three Sodbury, South West Five Downend & Bromley Heath, Downend Ten Stoke Gifford, Central Nine Downend & Bromley Heath, Staple Hill Two Stoke Gifford, University Three Doynton Five Stoke Lodge and the Common Nine Dyrham & Hinton Five Thornbury, Central Three Emersons Green, Badminton Three Thornbury, East Three Emersons Green, Blackhorse Three Thornbury, North East Four Emersons Green, Emersons Green Seven Thornbury, North West Three Emersons Green, Pomphrey Three Thornbury, South Three -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

The Shield Name the Shield Family in Pamington, Ashchurch

The Shield Name The Shield family have been living in Gloucestershire for at least 500 years. For a large part of that time the name Shield seems to have been interchangeable with the name Shill. The meaning of these names is unclear. In England the name Shield comes either from the occupational name for an armourer from the Middle English scheld meaning a shield, or from the Middle English schele meaning a hut, shed or shelter used by herdsmen as temporary accommodation in summer pastures. The name Shill, which seems to be peculiar to Gloucestershire, is unexplained. In Ireland the name Shield comes from the anglicised form of Ó Siadhail meaning a descendant of Siadhal . The name Shields, with the final ‘s’ is a habitational name for someone coming from North or South Shields in Northern England. The name Shield in Gloucestershire was also found with many alternative spellings. I have come across Shield, Sheild, Sheilde, Shelde, Sheyld, Shelyde, Shild, Shilde, Shyld and Shylde. There are rumours handed down in various branches of the family that the Shield family arrived in Gloucestershire from further north. In one case there is a story that two Shield brothers walked down from Scotland to Bristol. In another, the story is that a Shield farmer drove his cattle down from the north of England to Bristol for sale in the market, started to walk back, stopped in a pub and liked it so much that he used the money from the sale of the cattle to buy the pub and thus remained in Gloucestershire. -

WEEKLY LIST of PLANNING APPLICATIONS and OTHER PROPOSALS RECEIVED by the COUNCIL 05 August 2019 - 11 August 2019

WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND OTHER PROPOSALS RECEIVED BY THE COUNCIL 05 August 2019 - 11 August 2019 The proposals listed over the page have recently been received by the Planning Department. The application documents and plans may be viewed and commented on via the Internet. Please allow 7 days from the above date for the application to appear on the Council’s web site at www.southglos.gov.uk/planning. The submissions listed are also available online at the following one stop shop offices: • Thornbury Library, St Mary Street, Thornbury BS35 2AA • Civic Centre, High Street, Kingswood, South Gloucestershire, BS15 9TR • Yate One Stop Shop, Kennedy Way, Yate, South Gloucestershire Some large major applications are also available in hard copy. The Council Offices are open Monday to Thursday between the hours of 8.45 am and 5.00 pm and Friday between the hours of 8.45 am to 4.30 pm. If you have any queries regarding a proposal, please contact our Customer Service Centre on 01454 868004. Any comments on the proposals listed can be made online at the above website or sent in writing to South Gloucestershire Council P.O. BOX 2081 South Gloucestershire BS35 9BP. When commenting please quote the appropriate reference number and site address. All comments should be received within 21 days of the above date. Please note a copy of your comments will appear on the website. ABBREVIATIONS PT = Planning Thornbury PK = Planning Kingswood For suffix abbreviations in application number, see Application Type eg. /ADV = Advertisement South Gloucestershire Council Weekly List of Planning Applications: 05/08/2019 - 11/08/2019 PARISH NAME Almondsbury Parish Council APPLICATION NO P19/10572/F WARD NAME CASE OFFICER PLAN INSPECTION OFFICE Pilning And Severn Olivia Tresise Beach 01454 863761 LOCATION Washingpool Farm Main Road Easter Compton South Gloucestershire BS35 5RE PROPOSAL Change of use of hardstanding to form enlarged car park for the surfing lake development. -

Tales of the Vale: Stories from a Forgotten Landscape

Tales of the Vale: Stories from A Forgotten Landscape The view from St Arilda’s, Cowhill A collection of history research and oral histories from the Lower Severn Vale Levels (Photo © James Flynn 2014) Tales of the Vale Landscape 5 Map key Onwards towards Gloucestershire – Contents Shepperdine and Hill Tales of the Vale Landscape 4 Around Oldbury-on-Severn – Kington, Cowill, Oldbury Introduction 3 and Thornbury Discover A Forgotten Tales of the Vale: Landscape through our Tales of the Vale Landscape 3 walks and interpretation From the Severn Bridge to Littleton-upon-Severn – points Aust, Olveston and Littleton-upon-Severn 1. North-West Bristol – Avonmouth, Shirehampton and Lawrence Weston 6 Tales of the Vale Landscape 2 2. From Bristol to the Severn Bridge – From Bristol to the Severn Bridge – Easter Compton, Almondsbury, Severn Beach, Pilning, Redwick and Northwick 40 Easter Compton, Almondsbury, Severn Beach, Pilning, Redwick Walk start point and Northwick 3. From the Severn Bridge to Littleton-upon-Severn – Aust, Olveston and Littleton-upon-Severn 68 Interpretation Tales of the Vale Landscape 1 4. Around Oldbury-on-Severn – Kington, Cowill, Oldbury and Thornbury 80 North-West Bristol – Avonmouth, Shirehampton Toposcope and Lawrence Weston 5. Onwards towards Gloucestershire – Shepperdine and Hill 104 Contributors 116 (© South Gloucestershire Council, 2017. All rights reserved. © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100023410. Introduction to the CD 122 Contains Royal Mail data © Royal Mail copyright and database right 2017. Tales of the Vale was edited by Virginia Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2017. Bainbridge and Julia Letts with additional Acknowledgements 124 editing by the AFL team © WWT Consulting) Introduction Introducing Tales of the Vale Big skies: a sense of light and vast open space with two colossal bridges spanning the silt-laden, extraordinary River Severn. -

Bristol & Bath Car Services German Car Specialist

The Week in East Bristol & North East Somerset FREE Issue no 388 10th September 2015 Read by over 30,000 people every week In this week’s issue ...... page 9 Referendum for B&NES Mayor . Election petition successful page 22 Brislington library reprieved . But opening hours to be cut page 24 New schools open this term . New primary and studio schools ANext Tuesday's better public consultation exhibitionfuture very sensibly for Keynsham? brings together a number of issues concerning the future development of Keynsham over the next 15 years. The 'placemaking' operation which fleshes out the aims and ambitions of the Core Strategy and the Draft Transport Plan are key among these, but air quality management and the euphemistically named 'conservation area' strategy will all get an airing on 15th September at the Key Centre. One document you probably won't see there is called 'The Heart of Keynsham' but it is well worth getting your hands on a copy before you visit the exhibition or respond to the council consultation. Bath Hill East in 2 The Week • Thursday 3rd September 2015 e forIt has notKeynsham? been produced by B&NES officials or expensively recruited consultants, it has been written by local people who have witnessed the changes of the last two decades and considered the potential challenges for the future from the inside looking out. Author Terry Edwards lives in Mayfields and over the last 18 months has consulted with local residents and organisations, as well as wearing out a considerable amount of shoe leather walking around the Keynsham town centre and periphery to see Station Road if a better future could be imagined with just a little more courage and foresight. -

07 February 2021

WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND OTHER PROPOSALS RECEIVED BY THE COUNCIL 01 February 2021 – 07 February 2021 The proposals listed over the page have recently been received by the Planning Department. The application documents and plans may be viewed and commented on via the Internet. Please allow 7 days from the above date for the application to appear on the Council’s web site at www.southglos.gov.uk/planning. The submissions listed are also available online at the following one stop shop offices: • Patchway one Stop Shop, Rodway Road, Patchway, South Gloucestershire • Civic Centre, High Street, Kingswood, South Gloucestershire, BS15 9TR • Yate One Stop Shop, Kennedy Way, Yate, South Gloucestershire Some large major applications are also available in hard copy. The Council Offices are open Monday to Thursday between the hours of 8.45 am and 5.00 pm and Friday between the hours of 8.45 am to 4.30 pm. If you have any queries regarding a proposal, please contact our Customer Service Centre on 01454 868004. Any comments on the proposals listed can be made online at the above website or sent in writing to South Gloucestershire Council P.O. BOX 2081 South Gloucestershire BS35 9BP. When commenting please quote the appropriate reference number and site address. All comments should be received within 21 days of the above date. Please note a copy of your comments will appear on the website. ABBREVIATIONS For suffix abbreviations in application number, see Application Type eg. /ADV = Advertisement South Gloucestershire Council Weekly List of Planning Applications: 01/02/21 - 07/02/21 PARISH NAME Bitton Parish Council APPLICATION NO P21/00454/F WARD NAME CASE OFFICER PLAN INSPECTION OFFICE Bitton And Alex Hemming Oldland Common 01454 866456 LOCATION 6 Oakhill Avenue Bitton South Gloucestershire BS30 6JX PROPOSAL Change of use of existing integral garage to Hair Salon (Use Class E) (retrospective).