The Population of County Tyrone 1600-1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Transport and Safety Measures, Bridges and Street Lighting Draft Programme

Local Transport and Safety Measures, Bridges and Street Lighting Draft Programme Mid Ulster District Council Area 2017-2019 5 December 2016 A4 Ballagh Road at Ashfield Road Junction, Clogher Carriageway resurfacing with right turn lane provision CONTENTS P AG E Foreword 5/6 Carriageway Improvements A29 Moneysharvin Rd, Maghera 6 B162 Disert Rd, Draperstown 7 B43 Newell Rd at Lisnahull Rd, Dungannon 8 A29 Cookstown Rd, Dungannon 9 B83 Old Monaghan Rd, Clogher 10 A45 Ballynakilly Road at Creenagh Bridge, Coalisland 11 A45 Granville Rd, Dungannon 12 B161 Mountjoy Rd, Mountjoy 13 A29 Killytoney, Tobermore 14 A505 Drum Road, Cookstown 15 Sightline Improvements C560 Aughrim Rd / Gracefield Rd, Magherafelt 16 U5024 Gorteade Rd / B75 Kilrea Rd, Upperlands 17 B35 Granville Rd at Killyliss Rd 18 C645 Gorestown Rd at Mullybrannon Rd 19 B160 Annaghquin Rd/U816 Drumballyhugh Rd/U920 20 Gortvale Rd/U821 Drummond Rd, Rock U830 Tullyard Road, Sandholes 21 B4 Pomeroy Road/Knockaleery Road, Cookstown 22 Footways U5033 Craigadick Road, Maghera 23 U5180 Westland Rd, Magherafelt 24 Cunninghams Lane, Dungannon 25 Killymaddy Knox, Dungannon 26 C684 Ballygawley Rd, Dungannon 27 B18 Ballyneill Rd, Ballyronan 28 B520 Hillhead Rd, Stewartstown 29 U808 North St, Pomeroy 30 Page | 2 C565 Muff Rd, Churchtown 31 B161 St Patricks’ PS, Ardboe 32 Cycling Provision Fountain Road, Cookstown 33 Killyman Rd, Dungannon 34 A4 Crossowen Road, Augher to Clogher 35 Traffic Management Dungannon A29 Route Strategy 36 Thomas Street Roundabout 37 Moy Rd, Main Rd, Moygashel 38 Park -

8.4 6.1 8.2 3.4 7.4 4.1 3.1 9.2 5.1 1.2 7.1

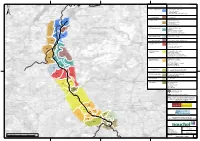

Landscape Character Zone (LCZ) Landscape Sub Zones (LCSZ) LCZ 1 Lower Foyle Valley 1.1 New Buildings & Ballougry Hill 1.2 River Foyle Meander 1.3 Foyle Floodplain 1.4 Burn Dennet & Glenmornan River Valleys LCZ 2 Gortmonly Hill 2.1 Gortmonly Hill LCZ 3 Lifford Hills 3.1 Binnion & Black Hill 1.1 3.2 Cavan & Dramore Hills 3.3 Croaghan Hill 3.4 Southern Lifford Hills 1.2 LCZ 4 Upper Foyle Valley 4.1 Knockavoe & Meenashesk 3.1 2.1 Hill Slopes 4.2 Enclosed River Mourne Valley 4.3 Newtownstewart Floodplain 4.4 Owenkillew Valley & Plateau Bogs 1.3 1.4 LCZ 5 Lower Derg Valley 5.1 Derg Valley Farmland 3.2 LCZ 6 Western Sperrins 6.1 Meenashesk Highland Bogs and Forest LCZ 7 Strule Valley and 7.1 Baronscourt Valley Bessy Bell 7.2 Bessy Bell 7.3 Enclosed River Strule Valley 7.4 Sperrins Lower Slopes 3.3 U1 4.1 LCZ 8 Omagh Drumlin 8.1 Wooded River Strule Valley Farmlands 8.2 Fairy Water Drumlins 6.1 8.3 Crockavanny Drumlins U2 8.4 South Omagh Drumlin Farmlands 8.5 Eskragh Water & Routing Burn Drumlins 3.4 4.2 LCZ 9 Brougher and 9.1 Slievelahan Farmlands Slievemore Ridgeline 9.2 Crocknatummoge Hillform 9.3 Garvaghy Valley 4.4 9.4 Beltany & Tullanafoile Farmlands 9.5 Knockmany Ridgeline 4.3 9.6 Ballymackilroy Moraines 5.1 U3 LCZ 10 Clogher Valley 10.1 Clogher & Augher Drumlin Farmlands 7.3 10.2 Ballygawley & Ballyreagh A4 Corridor 7.1 LCZ 11 Blackwater Valley 11.1 Black Hill & Aughnacloy Drumlins 7.2 7.4 11.2 Blackwater Drumlins 11.3 Favour Royal Forest LCZ 1 Branny Hill 12 1 Branny Hill 8.1 Urban Centres U1: Strabane & Lifford 8.2 U2: Sion Mills U3: Newtownstewart U4: Omagh U5: Aughnacloy U4 8.3 PROPOSED SCHEME SETTLEMENTS NORTHERN IRELAND BOUNDARY REPRODUCED FROM ORDNANCE SURVEY OF NORTHERN IRELAND'S DATA WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE CONTROLLER OF HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE, 8.4 © CROWN COPYRIGHT AND DATABASE RIGHTS NIMA ES&LA214. -

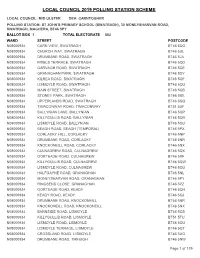

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER POLLING STATION: ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 882 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QG N08000934CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH BT46 5UL N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5JA N08000934FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH BT46 5QD N08000934GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QE N08000934GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5DY N08000934KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QF N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH BT46 5QB N08000934STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5BE N08000934UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QQ N08000934TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY BT51 5UF N08000934BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QP N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QR N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QU N08000934BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL) BT46 5PX N08000934CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY BT46 5NP N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NX N08000934CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QX N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5RF N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QW N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QU N08000934HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5NL N08000934MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PY N08000934RINGSEND CLOSE, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PZ N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QH N08000934KEADY ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QJ N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NX N08000934BARNSIDE ROAD, LISMOYLE -

DCSDC Planning Strabane Weekly Tyrone Constitution 01.07.2021 2Clms X 140Mm Draft 1.Pdf 1 22/06/2021 12:48:03

DCSDC_Planning_Strabane Weekly Tyrone Constitution_01.07.2021_2clms x 140mm_draft 1.pdf 1 22/06/2021 12:48:03 PLANNING APPLICATIONS Full details of the following planning applications including plans, maps and drawings are available to view on the NI Portal at www.planningni.gov.uk or alternatively as the Planning Oce is currently closed to public access, please contact 02871 253253 to seek alternative options to view the information you require. Written comments should be submitted within the next 14 days. Please quote the application number in any correspondence and note that all representations made, including objections, will be posted on the NI Planning Portal. Initial Advertisements APPLICATION LOCATION PROPOSAL LA11/2021/0638/O Lands adjacent to Gap site Derg and North of 16 Laghel Road, Castlederg, BT81 7RT LA11/2021/0642/F 67 Melmount Road, Single storey rear Derg Strabane, BT82 9PX extension to existing C dwelling and domestic garage M LA11/2021/0648/F 250 M. West of 26 Erection of a circular Derg Deerpark Road, pre-cast concrete Ardstraw, store with gas tight Y Newtownstewart, cover to provide BT78 4LA additional storage for CM processed anaerobic digestate LA11/2021/0656/F 16 Carricklynn Rear single storey MY Derg Avenue, Strabane, extension BT82 9BF CY LA11/2021/0639/F 5 Liscurry Gardens, Ramp and car Sperrin Artigarvan, Co. hardstanding at side Tyrone, BT82 0JH of dwelling CMY LA11/2021/0645/F 320 Lisnafin Park, Single storey rear Sperrin Strabane, BT82 9DN extension to dwelling, K access ramp & hand rails LA11/2021/0653/O 32 M. N of 80 Proposed new Sperrin Slieveboy Road, dwelling and garage Claudy, BT47 4AS LA11/2021/0657/F 15 The Brambles, Proposed rear play Sperrin Ballymagorry, area with access ramp Strabane, BT82 8TB to side of dwelling LA11/2021/0663/F 13 Castle Street, Retrospective Sperrin Strabane, BT82 8AF approval of 2 No. -

DCSDC Planning Strabane Chronicle Ulster Herald 21.01.2021 2Clms X 230Mm Draft 1.Pdf 1 12/01/2021 17:25:06

DCSDC_Planning_Strabane Chronicle Ulster Herald_21.01.2021_2clms x 230mm_draft 1.pdf 1 12/01/2021 17:25:06 PLANNING APPLICATIONS Full details of the following planning applications including plans, maps and drawings are available to view on the NI Portal at www.planningni.gov.uk or alternatively as the Planning Oce is currently closed to public access, please contact 02871 253253 to seek alternative options to view the information you require. Written comments should be submitted within the next 14 days. Please quote the application number in any correspondence and note that all representations made, including objections, will be posted on the NI Planning Portal. Initial Advertisements APPLICATION LOCATION PROPOSAL LA11/2021/0023/O Site adjacent to and Proposed dwelling Derg immediately N.E. of 9 and detached Kilcroagh Road, domestic garage Castlederg, BT81 7EG LA11/2021/0028/O 380M. S.W. of 109 Erection of Dwelling Derg Peacock Road, Sion Mills, Strabane, BT82 9NF LA11/2021/0029/F 11 & 11a Castletown New covered/open Derg Road, Strabane sided canopy to rear of nursery to allow children to play outside LA11/2021/0031/F 15 Derg Road, Proposed single Derg Victoria Bridge, storey extension to Strabane, Co. Tyrone, existing fish BT82 9JW processing unit LA11/2021/0002/F 50 Magherabrack Proposed single Sperrin Road, Upper Barnes, storey side extension Plumbridge, to provide BT79 8EN self-contained 'Granny Annex' accommodation LA11/2021/0003/O 30M. West of 128 Proposed dwelling Sperrin Lisnaragh Road, and domestic garage Donemana, Co. Tyrone, -

Announced Care Inspection Report 10 February 2017 Clogher Valley

Announced Care Inspection Report 10 February 2017 Clogher Valley Dental Care (Fivemiletown) Type of service: Independent Hospital (IH) – Dental Treatment Address: 86 Main Street, Fivemiletown, BT75 0PW Tel no: 028 8952 1177 Inspectors: Emily Campbell and Stephen O’Connor www.rqia.org.uk Assurance, Challenge and Improvement in Health and Social Care RQIA ID: 11438 Inspection ID: IN027327 1.0 Summary An announced inspection of Clogher Valley Dental Care, Fivemiletown, took place on 10 February 2017 from 10:00 to 12:29. The inspection sought to assess progress with any issues raised during and since the last care inspection and to determine if the practice was delivering safe, effective and compassionate care and if the service was well led. Mr Richard Graham, registered person, operates two dental practices; Clogher Valley Dental Care, Fivemiletown, and Clogher Valley Dental Care, Clogher. Some information pertaining to this inspection was reviewed at the Clogher Valley Dental Care, Clogher, practice as part of the inspection process Is care safe? Observations made, review of documentation and discussion with Mr Richard Graham, registered person, Mrs Graham, registered manager, and a receptionist/dental nurse demonstrated that further development is needed to ensure that care provided to patients is safe and avoids and prevents harm. Areas reviewed included staffing, recruitment and selection, safeguarding, management of medical emergencies, infection prevention control and decontamination, radiology and the general environment. Two requirements and seven recommendations were made to progress improvement. The two requirements were made in relation to validation of decontamination equipment and radiology. Three recommendations were made in relation to the staff register, staff appraisal and training records. -

Contact Information: Augher Central Primary School 17 Knockmany Road Augher Co Tyrone BT77 0BE

Contact Information: Augher Central Primary School 17 Knockmany Road Augher Co Tyrone BT77 0BE Tel. 028 8554 8443 www.augherprimary.co.uk Principal: Mrs A Sawyers BA (Hons), PGCE, PQH(NI), ALCM(TD) A school at the heart of the community-providing high quality education in a caring and stimulating learning environment. Augher Central Primary School is a thriving school in the heart of the Clogher Valley. We are committed to providing a high quality education in a stimulating and caring learning environment. In Augher we strive to offer an education which gives children a love for . learning, broadens their horizons and provides the skills and strategies to enable them to make life choices. All children are unique and talented, we celebrate the uniqueness and success of every pupil. We have high expectations for achievement and behavior in all aspects of schools life. At school we focus on the all round development of the child catering for personal, social and academic needs of our pupils. Throughout their primary school education we expect pupils to become independent and confident learners and workers who are highly motivated and are being nurtured to become citizens of the future. We are delighted with our most recent Inspection Report which recognized the quality of education at Augher Central as being ’Very Good to Outstanding’ in all areas. Over the last few years the school has opening three new extension wings and we are proud to have first class facilities to help us deliver child centered education. Augher Central is a family school where we promote a caring and Christian ethos. -

A Seed Is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA from the Earliest Times, The

A Seed is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA From the earliest times, the people of Ireland, as of other countries throughout the known world, played ball games'. Games played with a ball and stick can be traced back to pre-Christian times in Greece, Egypt and other countries. In Irish legend, there is a reference to a hurling game as early as the second century B.C., while the Brehon laws of the preChristian era contained a number of provisions relating to hurling. In the Tales of the Red Branch, which cover the period around the time of the birth of Christ, one of the best-known stories is that of the young Setanta, who on his way from his home in Cooley in County Louth to the palace of his uncle, King Conor Mac Nessa, at Eamhain Macha in Armagh, practised with a bronze hurley and a silver ball. On arrival at the palace, he joined the one hundred and fifty boys of noble blood who were being trained there and outhurled them all single-handed. He got his name, Cuchulainn, when he killed the great hound of Culann, which guarded the palace, by driving his hurling ball through the hound's open mouth. From the time of Cuchulainn right up to the end of the eighteenth century hurling flourished throughout the country in spite of attempts made through the Statutes of Kilkenny (1367), the Statute of Galway (1527) and the Sunday Observance Act (1695) to suppress it. Particularly in Munster and some counties of Leinster, it remained strong in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Brave Record Issue 6

Issue 6 Page !1 Brave Record Dungannon and Moy’s rich and varied naval service - Submariner WW1 - Polar expertise aided Arctic convoys - Leading naval surgeon - Naval compass inventor - Key role at Bletchley Park Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 6 Page !2 Moy man may be Northern Ireland’s first submariner loss HM Submarine D5 was lost on 03/11/1914. In the ship was 29 year old Fred Bradley. He had previously served during the Boer War. He had also served in HMS Hyacinth in the Somali Expedition. HMS D5 was a British D class submarine built by Vickers, Barrow. D5 was laid down on 23/2/1910, launched 28/08/1911 and was commissioned 19/02/1911. One source states she was sunk by a German mine laid by SMS Stralsund after responding to a German attack on Yarmouth by cruisers. The bombardment, which was very heavy and aimed at the civilian population, was rather ineffective, due to the misty weather and only a few shells landed on the beaches at Gorleston. In response, the submarines D3, E10 and D5 - the latter being under the command of Lt.Cdr. Godfrey Herbert, were ordered out into the roadstead to intercept the enemy fleet. Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 6 Page !3 Another source states HMS D5 was sunk by a British mine two miles south of South Cross Buoy off Great Yarmouth in the North Sea. 20 officers and men were lost. There were only 5 survivors including her Commanding Officer. -

Planning Applications Validated - for the Period 01/05/2020 to 31/05/2020

Planning Applications Validated - For the Period 01/05/2020 to 31/05/2020 Reference Number Proposal Location Application Type Agent Name & Address LA09/2020/0522/NMC Reduction to the overall 80 m SW of 11 Non CQ Architects floor area of the dwelling, Clonvaddy Road Material 23 Dunamore Road design of dwelling same Cabragh Change Cookstown as that approved under Dungannon BT80 9RP LA09/2018/1594/F LA09/2020/0523/O Proposed residential Lands between Outline Vision Design development Lindsayville and 31 Rainey Street Ballyneil Road and to Magherafelt the rear of 122-128 BT45 5DA Shore Road and to the rear of 1-6 Lovedale Ballyronan LA09/2020/0524/O Replacement dwelling 16 Derrygonigan Road Outline Robin Gibson and garage Cookstown 25 Ballinderry Bridge Road Coagh Cookstown BT80 0BR LA09/2020/0525/F Single storey rear extension 16 Beatrice Villas Full Diamond Architecture to dwelling Bellaghy 77 Main Street Maghera BT46 5AB LA09/2020/0526/O Site for replacement dwelling Adjacent to Outline Gibson Design & Build 1 Ballymulligan Road 25 Ballinderry Bridge Road Magherafelt Coagh Cookstown BT80 0BR LA09/2020/0527/F Single storey dwelling with Approximately 80m Full Hamill Architects Unit T2 attached garage. west of 125 Sherrigrim Dungannon Enterprise Road Centre Sandholes Dungannon Cookstown BT71 6JT LA09/2020/0529/F Proposed replacement 30m South West of 22 Full Diamond Architecture dwelling and domestic Sixtowns Road 77 Main Street garage Draperstown Maghera BT46 5AB LA09/2020/0530/F Proposed replacement 5 Fogart Road Full Paul Mc Mahon dwelling and provision of Clogher 26 Bracken Vale domestic garage Omagh BT78 5RS LA09/2020/0531/O New dwelling and garage on 75m North East of Outline J O Dallas Associates a farm 17 Tirnony Road 31Abbey Street Maghera Coleraine BT52 1DU LA09/2020/0532/RM Proposed dwelling and Approx 45m South Reserved Matters CMI Planners Ltd domestic double garage of 48 Rossmore 38b AirfieldRoad (Amended Access) Road Dungannon Toomebridge BT41 3SG LA09/2020/0533/NMC Minor changes to floor 200m N.W. -

Smythe-Wood Series A

Smythe-Wood Newspaper Index – “A” series – mainly Co Tyrone Irish Genealogical Research Society Dr P Smythe-Wood’s Irish Newspaper Index Selected families, mainly from Co Tyrone ‘Series A’ The late Dr Patrick Smythe-Wood presented a large collection of card indexes to the IGRS Library, reflecting his various interests, - the Irish in Canada, Ulster families, various professions etc. These include abstracts from various Irish Newspapers, including the Belfast Newsletter, which are printed below. Abstracts are included for all papers up to 1864, but excluding any entries in the Belfast Newsletter prior to 1801, as they are fully available online. Dr Smythe-Wood often found entries in several newspapers for the one event, & these will be shown as one entry below. Entries dealing with RIC Officers, Customs & Excise Officers, Coastguards, Prison Officers, & Irish families in Canada will be dealt with in separate files, although a small cache of Canadian entries is included here, being families closely associated with Co Tyrone. In most cases, Dr Smythe-Wood has recorded the exact entry, but in some, marked thus *, the entries were adjusted into a database, so should be treated with more caution. There are further large card indexes of Miscellaneous notes on families which are not at present being digitised, but which often deal with the same families treated below. ANC: Anglo-Celt LSL Londonderry Sentinel ARG Armagh Guardian LST Londonderry Standard/Derry Standard BAI Ballina Impartial LUR Lurgan Times BAU Banner of Ulster MAC Mayo Constitution -

Bushwacker Rally 2015

Bushwacker Rally 2015 seeded Driver Town Co Driver Town Car Class 1 Josh Moffett Clontibret Jason McKenna Emyvale Evo 9 9 2 Desi Henry Portglenone Liam Moynihan Millstreet Fabia S2000 9 3 Mark Donnelly Omagh Barry McNulty Enniskillen Impreza S10 9 4 Kenny McKinstry Banbridge Noel Orr Bangor Impreza S14 8 5 Mark Donnelly Greencastle Stephen O'Hanlon Ballygawley Evo 9 9 6 James Gillin Castlederg John Bustard Sydney Subura Impreza 8 7 Michael Carbin Monaghan Darragh Kelly Monaghan Evo 4 9 8 Jonny Leonard Ballinamallard Nial Burns Sligo Evo 9 9 Niall Henry Portglenone John Rowan Cushendall Impreza 8 10 Adrian Hetherington Donaghmore Gary Nolan Wexford Escort Mk 2 7 11 Frank Kelly Moy Sean Ferris Drumquin Escort Mk2 7 12 Shane McGirr Fivemiletown Jackie Elliott Ballinamallard Starlet 6 14 Vivan Hamill Ballygawley Paul Hamill Ballygawley Escort RS 7 15 Seamus O'Connell Dungiven Sean Magee Castledawson Escort Mk2 7 16 Paul Barrett Omagh Dermot Colgan Loughmacrory Escort MK 2 5 17 Paul Britton Donemana Peter Ward Donemana Impreza 2 18 Niall McCullagh Omagh Ryan McCloskey Omagh Evo 6 9 19 Darren Mckelvey Castlederg Denver Rafferty Ballygawley Evo 9 9 20 John Cairns Strabane James Cairns Strabane Evo 9 21 Gareth Mimnagh Omagh Barry McCarney Isle of Man Evo 2 22 Frank O'Brien Omagh Stephen O'Brien Omagh Evo 6 9 23 Dermot O'Hagan Omagh Pierce Doheny Jnr Blackrock Evo 6 9 24 Cathan McCourt Dromore Brian Hoy Enniskillen Evo 9 2 25 Andy Bustard Castlederg TBA Evo 7 9 26 Alan Smyth Omagh Macartan Keirans Monaghan Citroen C2R2 4 27 Rob Duggan Killarney