EDB Eurasian Integration Yearbook 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukrainian and Russian Waterways and the Development of European Transport Corridors

European Transport \ Trasporti Europei n. 30 (2005): 14-36 Ukrainian and Russian waterways and the development of European transport corridors Michael Doubrovsky1∗ 1Odessa National Maritime University, Odessa, Ukraine Abstract Four of the nine international transport corridors pass through the territory of Ukraine: №3, №5, №7, and №9. In recent years Ukraine conducted an active policy supporting the European initiatives on the international transport corridors and offered variants of corridors to the European community. In the field of a water transport it is planned to carry out the construction of new and reconstruction of existing infrastructure (regarding corridors № 9; TRACECA; Baltic - Black Sea) in the main Ukrainian ports. The paper considers the situation in the Ukrainian waterways as a part of the international transport corridors. It presents an analysis of the existing situation and some planning measures. In order to optimize and rationally development the inland waterways and seaports of the Black Sea – Azov Sea region it is necessary to speed up the working out and official approval of the regional transport ways network. Regarding Ukrainian seaports this task is carried out within the framework of program TRACECA, and also by Steering Committee of Black Sea PETRA and working group on transport of the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation. To connect the new members countries of EU two approaches are considered: (1) the use of the Danube River due to restoration of navigation in its Ukrainian part, providing an exit to the Black Sea; (2) the creation of new inland water-transport links providing a more rational and uniform distribution of freight traffics from the Central and Northern Europe (using the third largest river in Europe - Dnepr River running into the Black Sea). -

List of Dams and Reservoirs 1 List of Dams and Reservoirs

List of dams and reservoirs 1 List of dams and reservoirs The following is a list of reservoirs and dams, arranged by continent and country. Africa Cameroon • Edea Dam • Lagdo Dam • Song Loulou Dam Democratic Republic of Congo • Inga Dam Ethiopia Gaborone Dam in Botswana. • Gilgel Gibe I Dam • Gilgel Gibe III Dam • Kessem Dam • Tendaho Irrigation Dam • Tekeze Hydroelectric Dam Egypt • Aswan Dam and Lake Nasser • Aswan Low Dam Inga Dam in DR Congo. Ghana • Akosombo Dam - Lake Volta • Kpong Dam Kenya • Gitaru Reservoir • Kiambere Reservoir • Kindaruma Reservoir Aswan Dam in Egypt. • Masinga Reservoir • Nairobi Dam Lesotho • Katse Dam • Mohale Dam List of dams and reservoirs 2 Mauritius • Eau Bleue Reservoir • La Ferme Reservoir • La Nicolière Reservoir • Mare aux Vacoas • Mare Longue Reservoir • Midlands Dam • Piton du Milieu Reservoir Akosombo Dam in Ghana. • Tamarind Falls Reservoir • Valetta Reservoir Morocco • Aït Ouarda Dam • Allal al Fassi Dam • Al Massira Dam • Al Wahda Dam • Bin el Ouidane Dam • Daourat Dam • Hassan I Dam Katse Dam in Lesotho. • Hassan II Dam • Idriss I Dam • Imfout Dam • Mohamed V Dam • Tanafnit El Borj Dam • Youssef Ibn Tachfin Dam Mozambique • Cahora Bassa Dam • Massingir Dam Bin el Ouidane Dam in Morocco. Nigeria • Asejire Dam, Oyo State • Bakolori Dam, Sokoto State • Challawa Gorge Dam, Kano State • Cham Dam, Gombe State • Dadin Kowa Dam, Gombe State • Goronyo Dam, Sokoto State • Gusau Dam, Zamfara State • Ikere Gorge Dam, Oyo State Gariep Dam in South Africa. • Jibiya Dam, Katsina State • Jebba Dam, Kwara State • Kafin Zaki Dam, Bauchi State • Kainji Dam, Niger State • Kiri Dam, Adamawa State List of dams and reservoirs 3 • Obudu Dam, Cross River State • Oyan Dam, Ogun State • Shiroro Dam, Niger State • Swashi Dam, Niger State • Tiga Dam, Kano State • Zobe Dam, Katsina State Tanzania • Kidatu Kihansi Dam in Tanzania. -

Download Paper

Chair Interbrew – Baillet Latour Working Papers No. 22 THE MAKING OF THE CONCEPT OF THE EU-RUSSIA COMMON ECONOMIC SPACE Evgeny Vinokurov The Making of the Concept of the EU-Russia Common Economic Space The Making of the Concept of the EU-Russia Common Economic Space Evgeny Vinokurov1 Abstract The paper starts with the analysis of the negotiation process leading to the adoption of the Concept of the Common Economic Space (CES) between the EU and Russia. Focusing on the Russian side, it delineates the phases and main activities of the negotiations. The paper comes to the conclusion that the negotiation process on Russia’s side was essentially of a top-down nature, with a dominant role of the governmental bureaucracies and little participation of the business community and the general public. The impact of the economic assessments and studies was limited, too. The paper proceeds with the analysis of the choice of a model for the CES envisaged in the Concept. It argues that the Concept of CES represents an original model in itself, combining elements of the EEA and ‘Swiss’ models; that is, it unites both horizontal and sectoral approaches. It is questionable whether the model envisaged 1 Evgeny Yuryevich Vinokurov is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations RAS, Moscow, and a visiting scholar at KULeuven (e-mail: [email protected]). The author gratefully acknowledges a research grant from the Chair Interbrew Baillet- Latour which enabled him to conduct this research. 1 Evgeny Vinokurov in the Concept is capable to provide a satisfactory solution to the policy-taker challenge. -

The Ineffectiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-29-2011 The neffecI tiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under Globalization: The aC se of Iraq Manuel De Leon Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI11081006 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Recommended Citation De Leon, Manuel, "The neffeI ctiveness of a Multinational Sanctions Regime Under Globalization: The asC e of Iraq" (2011). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 463. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/463 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE INEFFECTIVENESS OF MULTILATERAL SANCTIONS REGIMES UNDER GLOBALIZATION: THE CASE OF IRAQ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Manuel De Leon 2011 To: Dean Kenneth Furton College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Manuel De Leon, and entitled The Ineffectiveness of Multilateral Sanctions Regimes Under Globalization: The Case of Iraq, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Mohiaddin Mesbahi _______________________________________ Dario Moreno _______________________________________ Astrid Arraras _______________________________________ Ronald W. Cox, Major Professor Date of Defense: June 29, 2011 The dissertation of Manuel De Leon is approved. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Tajikistan, January 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: TAJIKISTAN January 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Tajikistan (Jumhurii Tojikiston). Short Form: Tajikistan. Term for Citizen(s): Tajikistani(s). Capital: Dushanbe. Other Major Cities: Istravshan, Khujand, Kulob, and Qurghonteppa. Independence: The official date of independence is September 9, 1991, the date on which Tajikistan withdrew from the Soviet Union. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1), International Women’s Day (March 8), Navruz (Persian New Year, March 20, 21, or 22), International Labor Day (May 1), Victory Day (May 9), Independence Day (September 9), Constitution Day (November 6), and National Reconciliation Day (November 9). Flag: The flag features three horizontal stripes: a wide middle white stripe with narrower red (top) and green stripes. Centered in the white stripe is a golden crown topped by seven gold, five-pointed stars. The red is taken from the flag of the Soviet Union; the green represents agriculture and the white, cotton. The crown and stars represent the Click to Enlarge Image country’s sovereignty and the friendship of nationalities. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: Iranian peoples such as the Soghdians and the Bactrians are the ethnic forbears of the modern Tajiks. They have inhabited parts of Central Asia for at least 2,500 years, assimilating with Turkic and Mongol groups. Between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C., present-day Tajikistan was part of the Persian Achaemenian Empire, which was conquered by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. After that conquest, Tajikistan was part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, a successor state to Alexander’s empire. -

Enhancing Access to Finance for Sme Development in Tajikistan

ENHANCING ACCESS TO FINANCE FOR SME DEVELOPMENT IN TAJIKISTAN IN DEVELOPMENT SME FOR FINANCE TO ACCESS ENHANCING ENHANCING ACCESS TO FINANCE РАСШИРЕНИЕ ДОСТУПА FOR SME DEVELOPMENT IN К ФИНАНСИРОВАНИЮ В PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT TAJIKISTAN ЦЕЛЯХ РАЗВИТИЯ МСП ТАДЖИКИСТАНА Policy Handbook Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the Малые и средние предприятия backbone of Tajikistan’s economy, (МСП) составляют костяк yet they face significant barriers экономики Таджикистана, однако in accessing finance. Accounting for испытывают серьезные трудности 50% of GDP, the large inflow of migrant при получении финансирования. Enhancing access remittances is an opportunity for Tajikistan to Один из способов укрепления финансового strengthen the financial sector. However, a number сектора страны заключается в грамотном to finance for SME of important challenges remain: a large proportion использовании денежных переводов, которые of remittances do not enter the formal banking поступают в большом объеме из-за рубежа development in system, and business creation by return migrants is и составляют 50% ВВП. Тем не менее, ряд limited. This Handbook presents recommendations существенных проблем все же сохраняется: to channel savings from remittances as a means значительная часть денежных переводов Tajikistan to improve access to finance and foster SME не поступает в банковскую систему, а development. вернувшиеся мигранты редко открывают собственные предприятия. В настоящем Расширение доступа This Handbook was peer reviewed on 26 November руководстве содержатся рекомендации о 2014 at the OECD Eurasia Competitiveness том, как способствовать формированию у к финансированию в Roundtable. The Roundtable is a policy network that населения сбережений за счет получаемых gathers OECD members and partner countries from денежных переводов в целях повышения целях развития МСП the Eurasia region for knowledge sharing on the доступности финансирования и развития МСП. -

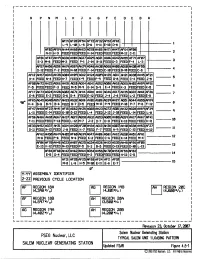

Salem Generating Station, Units 1 & 2, Revision 29 to Updated Final Safety Analysis Report, Chapter 4, Figures 4.5-1 to 4.5

r------------------------------------------- 1 I p M J B I R N L K H G F E D c A I I I I I Af'Jq AF20 AF54 AF72 32 AF52 AF18 I L-q L-10 L-15 D-6 -11 E-10 D-8 l I AF03 Af't;qAH44 AH60 AH63 AG70 AH65 AH7l AH47 AFS4 AF08 I N-ll H-3 FEED FEED FEED H-14 FEED FEED FEED M-12 C-11 2 I AF67 AH4q AH04 AG27 AG2<i' AG21 AG16 AG42 AF71 AF07 AF01 AG36 AH!5!5 3 I E-3 M-6 FEED M-3 FEED P-1 J-14 B-11 FEED D-3 FEED F-4 L-3 I AF67 AH5S AG56 Atflq AGsq AH2<1' AG48 AH30 AG68 AH08 AG60 AH30 AF55 I D-12 FEED F-2 FEED N-11 FEED F-14 FEED C-11 FEED B-11 FEED C-8 4 I AF12 AH57 AG43 AH38 AHtiJq AG12 AH24 AGfR AH25 AGil AG31 AH45 AF21 AGlM AH21 5 I H~4 FEED N-4 FEED H-7 FEED K~q FEED F-q FEED G-8 FEED C-4 FEED J-15 I AF50 AH72 AH22 AGS6 AH15 AGll.lAG64 AG41 AG52 AG88 AH18 AG65 AHIJ2 AH5q AF51 I F-5 FEED FEED F-3 FEED M-5 r+q G-14 o-q E-4 FEED K-3 FEED FEED K-5 6 I f:Fl7 AH73 AG24 AH28 AG82 AG71 AH14 AG18 AHil AG46 AG17 AH35 AG22 AH61 AF26 7 I E-8 FEED E-2 FEED G-6 G-4 FEED E-12 FEED J-4 J-6 FEED L-2 FEED E-5 I Af&q I qeo AF65 AG45 AtM0 AG57 AH33 AG32 AG16 AH01 AGI6 AG3<1' AH27 AG51 AG44 AG55 K-4 B-8 e-q B-6 FEED B-7 P-5 FEEC M-11 P-q FEED P-11 P-7 P-8 F-12 8 I AF47 AH68 AF23 AH41 AF1!5 AG62 AH26 AG03 AH23 AH32 AG28 AHsq AF3<1' q I L-U FEED E-14 FEED G-10 G-12 FEED L-4 FEED FEED L-14 FEED L-8 I ~~ AF66 AH66 AH10 AG67 AH37 AGJq AG68 AG3l AG63 AG05 AH08 AG5q AH17 AH67 AF41 I F-11 FEED FEED F-13 FEED L-12 M-7 J-2 D-7 D-11 FEED K-13 FEED FEED K-11 10 I AE33 AH!52 AG37 AH31 AG14 AH20 AF20 AH34 AG13 AH36 AG07 AH40 AG38 AH!53 AF27 I G-ll FEED N-12 FEED J-8 FEED K-7 FEED -

Exploitation of Oil Fields and Sustainable Development of the Environment

Mini Review Recent Adv Petrochem Sci Volume 4 Issue 1 - December 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Zhanna Mingaleva Exploitation of Oil Fields and Sustainable Development of the Environment Zhanna Mingaleva* Department of Economics and management in industrial production, Perm National Research Polytechnic University, Russia Submission: November 21, 2017 ; Published: December 14, 2017 *Corresponding author: Zhanna Mingaleva, Department of Economics and management in industrial production, Perm National Research Polytechnic University (PNRPU), 29, Komsomolsky Av., Perm, Russian Federation, 614990, Russia, Email: Abstract Development and exploitation of oil fields is one of the leading factors in the transformation of the natural environment of the Perm region. theThe water implementation reservoirs isof one programs of the key for featuresmonitoring of the the Perm environmental region, posing safety high of risks oil and to the gas environment. fields is considered as the actual task of sustainable development of the territory and improvement of the life quality. The existence and development of oil fields in karstic areas located closely to Keywords: Sustainable development; Pollution; Environment; Quality of life; Oil field Introduction Table 1: Structure of total recoverable hydrocarbon reserves by types of Perm region, 174 have been developed, half of which have been and categories. TMore than 231 oil and gas fields are opened at the territory operated for more than 30 years. Most of the multilayer deposits Total Recoverable Types of Hydrocarbon Deposits often have the so-called gas “cap”. The structure of the types of Reserves Oil of categories A+B+C1 514.94 million tons 1. The structure of the total recoverable reserves of oil and gas Oil of categories 66.704 million tons hydrocarbon fields located in the Perm Region is shown in Figure by types and categories is shown in Table 1. -

Evgeny Vinokurov EAEU Among Other Regional Integration

Evgeny Vinokurov EAEU Among Other Regional Integration Organizations: Comparative Analysis As concerns the ‘universe’ of regional integration organizations, the EAEU is a new kid on the block. As such, it should be compared with other regional and sub-regional organizations. A correct and realistic assessment of its successes and problems is often impeded by its direct and exclusive comparison with the paragon of regional integration — the European Union. However, for a more objective analysis of the EAEU's structural features, successes, and failures, it is useful to compare it with other major regional integration associations — NAFTA, MERCOSUR, Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf, ASEAN, and the South African Customs Union. Then everything falls into place. On the one hand, the Eurasian Economic Union is not a flawless "success story". After an initial phase of rapid growth, it hit a certain ceiling by 2016. On the other hand, it has managed to achieve quite a lot. The treaty and institutions are working. The common market for goods is functional, albeit with a number of exemptions. The common labour market is already operational — a huge and often underappreciated achievement. There has been substantial progress in developing common technical regulations, etc. Overall, the EAEU should be viewed not as an exception to the rules, but rather as one of the existing ‘customs unions +’ with its own achievements and problems.1 Its structural features are certainly important, but they are not unique — even those that seem so at first sight. Russia's economic dominance in the EAEU matches South Africa's weight in the South African Customs Union, which is even greater. -

Revised Draft Experiences with Inter Basin Water

REVISED DRAFT EXPERIENCES WITH INTER BASIN WATER TRANSFERS FOR IRRIGATION, DRAINAGE AND FLOOD MANAGEMENT ICID TASK FORCE ON INTER BASIN WATER TRANSFERS Edited by Jancy Vijayan and Bart Schultz August 2007 International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID) 48 Nyaya Marg, Chanakyapuri New Delhi 110 021 INDIA Tel: (91-11) 26116837; 26115679; 24679532; Fax: (91-11) 26115962 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.icid.org 1 Foreword FOREWORD Inter Basin Water Transfers (IBWT) are in operation at a quite substantial scale, especially in several developed and emerging countries. In these countries and to a certain extent in some least developed countries there is a substantial interest to develop new IBWTs. IBWTs are being applied or developed not only for irrigated agriculture and hydropower, but also for municipal and industrial water supply, flood management, flow augmentation (increasing flow within a certain river reach or canal for a certain purpose), and in a few cases for navigation, mining, recreation, drainage, wildlife, pollution control, log transport, or estuary improvement. Debates on the pros and cons of such transfers are on going at National and International level. New ideas and concepts on the viabilities and constraints of IBWTs are being presented and deliberated in various fora. In light of this the Central Office of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID) has attempted a compilation covering the existing and proposed IBWT schemes all over the world, to the extent of data availability. The first version of the compilation was presented on the occasion of the 54th International Executive Council Meeting of ICID in Montpellier, France, 14 - 19 September 2003. -

Divergence in Seasonal Hydrology Across Northern Eurasia: Emerging Trends and Water Cycle Linkages M

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 114, D18119, doi:10.1029/2009JD011747, 2009 Click Here for Full Article Divergence in seasonal hydrology across northern Eurasia: Emerging trends and water cycle linkages M. A. Rawlins,1 H. Ye,2 D. Yang,3 A. Shiklomanov,4 and K. C. McDonald1 Received 13 January 2009; revised 16 June 2009; accepted 19 June 2009; published 24 September 2009. [1] Discharge from large Eurasia rivers increased during the 20th century, yet much remains unknown regarding details of this increasing freshwater flux. Here, for the three largest Eurasian basins (the Ob, Yenisei, and Lena) we examine the nature of annual and seasonal discharge trends by investigating the flow changes along with those for precipitation, snow depth, and snow water equivalent. On the basis of a multiperiod trend analysis and examination of station data, we propose two characteristic regimes to explain the long-term discharge increase from these large Eurasian rivers. Over the early decades from approximately 1936 to 1965, annual precipitation correlates well with annual discharge, and positive discharge trends are concurrent with summer/fall discharge increases. The latter decades were marked by a divergence between winter/ spring flows, which increased, amid summer/fall discharge declines. A comparison of cold season precipitation (CSP) and spring discharge trends across subbasins of the Ob, Yenisei, and Lena shows limited agreement with one precipitation data set but good agreement (R2 > 0.90) when a second is used. While natural variability in the Arctic system tends to mask these emerging trends, spatial and temporal changes can generally be characterized by increased solid precipitation, primarily to the north, along with a drier hydrography during the warm season. -

Negativliste. Fossil Energi

Bilag 6. Negativliste. Fossil energi Maj 2017 Læsevejledning til negativlisten: Moderselskab / øverste ejer vises med fed skrift til venstre. Med almindelig tekst, indrykket, er de underliggende selskaber, der udsteder aktier og erhvervsobligationer. Det er de underliggende, udstedende selskaber, der er omfattet af negativlisten. Rækkeetiketter Acergy SA SUBSEA 7 Inc Subsea 7 SA Adani Enterprises Ltd Adani Enterprises Ltd Adani Power Ltd Adani Power Ltd Adaro Energy Tbk PT Adaro Energy Tbk PT Adaro Indonesia PT Alam Tri Abadi PT Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd Africa Oil Corp Africa Oil Corp Alpha Natural Resources Inc Alex Energy Inc Alliance Coal Corp Alpha Appalachia Holdings Inc Alpha Appalachia Services Inc Alpha Natural Resource Inc/Old Alpha Natural Resources Inc Alpha Natural Resources LLC Alpha Natural Resources LLC / Alpha Natural Resources Capital Corp Alpha NR Holding Inc Aracoma Coal Co Inc AT Massey Coal Co Inc Bandmill Coal Corp Bandytown Coal Co Belfry Coal Corp Belle Coal Co Inc Ben Creek Coal Co Big Bear Mining Co Big Laurel Mining Corp Black King Mine Development Co Black Mountain Resources LLC Bluff Spur Coal Corp Boone Energy Co Bull Mountain Mining Corp Central Penn Energy Co Inc Central West Virginia Energy Co Clear Fork Coal Co CoalSolv LLC Cobra Natural Resources LLC Crystal Fuels Co Cumberland Resources Corp Dehue Coal Co Delbarton Mining Co Douglas Pocahontas Coal Corp Duchess Coal Co Duncan Fork Coal Co Eagle Energy Inc/US Elk Run Coal Co Inc Exeter Coal Corp Foglesong Energy Co Foundation Coal