Supplying Clean Water to Jaipur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brieff Summary

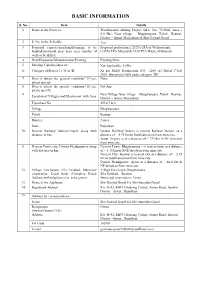

BASIC INFORMATION S. No. Item Details 1. Name of the Project/s Waollastonite Mining Project (M.L. No- 73/2002, Area – 5.0 Ha.) Near village – Bhagwanpura, Tehsil– Beawar, District – Ajmer (Rajasthan) of Shri Govind Goyal. 2. S. No. in the Schedule 1(a). 3. Proposed capacity/area/length/tonnage to be Proposed production@ 23296 TPA of Walloastonite handled/command area/ lease area /number of (13978 TPA Mineral & 9318 TPA Waste of Mineral) wells to be drilled. 4. New/Expansion/Modernization/Existing Exciting Mine 5. Existing Capacity/Area etc. Not Applicable/ 5.0Ha. 6. Category of Project i.e 'A' or 'B' As per MoEF Notification S.O. 2269 (E) Dated 1th July 2016, thus project falls under category “B1” 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes, None please specify. 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes, Not Any please specify. 9. Near Village Near village – Bhagwanpura, Tehsil– Beawar, Location of Villages and Khasra nos. with Area District – Ajmer (Rajasthan) Toposheet No. 45J/4,7 & 8 Village Bhagwanpura Tehsil Beawar District Ajmer State Rajasthan 10. Nearest Railway Station/Airport along with Beawar Railway Station is nearest Railway Station, at a distance in km. distance of ~ 5.95 km in South direction from mine site. Jaipur Airport, is at a distance of ~ 179 km in NE direction from mine site. 11. Nearest Town, city, District Headquarters along Nearest Town- Bhagwanpura - is nearest town at a distance with distance in km. of ~ 1.33 km in NNE direction from mine site. Nearest City- Beawar is nearest city at a distance of ~ 5.95 km in South direction from mine site. -

Characteristics of Pegmatoidal Granite Exposed Near Bayalan, Ajmer District, Rajasthan

Characteristics of pegmatoidal granite exposed near Bayalan, Ajmer district, Rajasthan Nilanjan Dasgupta1,∗, Taritwan Pal2, Joydeep Sen1 and Tamoghno Ghosh1 1Department of Geology, Presidency University, 86/1 College Street, Kolkata 700 073, India. 2Department of Geology and Geophysics, IIT Kharagpur, Midnapore, West Bengal, India. ∗e-mail: [email protected] The study involves the characterization of pegmatoidal granite, southeast of Beawar, Ajmer district, Rajasthan. Earlier researchers had described this granite as part of the BGC, basement to the Bhim Group of the Delhi Super Group rocks. However, the present study indicates that it is younger than the rocks of Bhim Group of South Delhi Fold Belt, into which it is intrusive. The intrusion is structurally controlled and the outcrop pattern is phacolithic. The granite had intruded post-D2 deformation of the Delhi orogeny along the axial planes of D2 folds. The intrusion has also resulted in the formation of a contact aureole about the calc gneisses. 1. Introduction host rocks by this emplacement have been studied. An attempt is made to fix the time of emplacement A long geological history since Middle Archaean with respect to the different deformational events is recorded in the Precambrian belt of Rajasthan. of the Delhi orogeny. The rocks of the study area fall within the The granites were earlier classified as basement ‘Delhi System’, defined in the pioneering study of rocks of pre-Delhi age (Heron 1953; Gupta 1934), Heron (1953), and now rechristened as the Delhi which is contrary to the present findings. Supergroup (Gupta and Bose 2000 and references therein) (figure 1). Within the study area around the small village of Bayalan, 10 km southeast of Beawar in Ajmer district of Rajasthan, pegma- 2. -

Rajputana & Ajmer-Merwara, Vol-XXIV, Rajasthan

PREFACE CENSUS TAKING, IT HAS RECENTLY BEEN explained by the Census Commissioner for India, should be regarded primarily as a detached collection and presentation of certain facts in tabular form for the use and consultation of the whole country, and, for that matter, the whole world. Conclusions are for ot.hers to draw. It is upon this understanding of their purpose that Tables have been printed in this volume with only the ,barest notes necessary to explain such points as definitions, change of areas, etc. But perhaps the word , barest' is too bare and requires some covering. In the past it has been customary to preface the Tables with many pages of text, devoted to providing some general description of the area concerned and supported by copious Subsidiary Tables and comparisons with data collected in other provinces, countries and states. On this occasion there is no prefatory text, no provision of extraneous comparisons, and Subsidiary Tables have virtually been made part of the Tables themselves. We may agree that the present method of presentation has much to recommend it. Those who seriously study census statistics at least can be presumed to be able to draw their own deductions: they do not need a guide constantly at their side, and indeed may actually resent his well-intentioned efforts. All that they require are t,he bare facts. Yet such people must ever constitute a very small minority. 'Vhat of the others-the vast majority of the public? It is hardly to be expected that they can be lured to Census Tavern by the offer of such coarse fare. -

Exec Summary

STUDY ON PLANNING OF WATER RESOURCES OF RAJASTHAN Executive Summary Project Background The State Water Policy of Government of Rajasthan, February 2010, provides for development of its Water resources in a well planned way. All new projects shall be planned based on micro watershed planning basis so as to ensure equity in use of surplus water. It is on this account that the Government of Rajasthan took up study to review and update all River Basin Master Plans for the integrated development and management of all its water resources. In this connection necessary provision of funds were made in EC funded State Partnership Program (SPP) under implementation in Rajasthan State. The earlier comprehensive study on water planning for different river basins in Rajasthan State was carried out by TAHAL-WAPCOS Consultants during year 1994-1998. This study was considered quite old and had much reduced relevance in today’s context. The present study therefore envisages to take-up review and fresh planning of all the water resources of Rajasthan based on updated water resources data and modern techniques now available in this field of study encompassing all necessary provisions made in the new water policy of the State Government. The purpose of this assignment is to prepare a long term plan and policy for development and management of the water resources of the State of Rajasthan, both surface (internal and external) and ground water, on comprehensive and integrated basis. The period of planning envisaged is 2010-2060. Scope of Work 1. Data Collection 2. Analysis of Agroclimatic Zone wise hydrology, temperature over a period of 20 years, find all changes in precipitation, no. -

Ras-Beawar-Mandal Road National Highway158 Rajasthan

MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT & HIGHWAYS Govt. of India Public Disclosure Authorized Ras-Beawar-Mandal Road National Highway158 Rajasthan Start Point - Ras Km 0+000 Public Disclosure Authorized Beawar Public Disclosure Authorized End Point - Mandal Km 116+900 Environmental Impact Assessment and Environment Management Plan Public Disclosure Authorized Revised Draft Report November 30, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.1 Project Background ................................................................................................... 1.2 Project Location ........................................................................................................ 1.3 Environmental Screening and Project Salient Features ............................................ 1.4 Objective of Project .................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.5 Objective of EIA Study .............................................................................................. 1.6 Approach and Methodology ..................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.6.1 Reconnaissance Survey ................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.6.2 Desk Review ..................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.6.3 Review of Applicable Environmental RegulationsError! Bookmark not defined. 1.6.4 International Agreements .................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.6.5 -

ELECTION LIST 2016 10 08 2016.Xlsx

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SCIENCE MOHANLAL SUKHAIDA UNIVERSITY, UDAIPUR FINAL ELECTORAL LIST 2016-17 B. SC. FIRST YEAR Declared on : 10-08-2016 S. No. NAME OF STUDENT FATHER'S NAME ADDRESS 1 AAKASH SHARMA VINOD KUMAR SHARMA E 206 DWARIKA PURI 2 ABHA DHING ABHAY DHING 201-202, SUGANDHA APARTMENT, NEW MALI COLONY, TEKRI, UDAIPUR 3 ABHISHEK DAMAMI GHANSHYAM DAMAMI DAMAMIKHERA,DHARIYAWAD 4 ABHISHEK MISHRA MANOJ MISHRA BAPU BAZAR, RISHABHDEO 5 ABHISHEK SAYAWAT NARENDRA SINGH SAYAWAT VILL-MAKANPURA PO-CHOTI PADAL TEH GHATOL 6 ABHISHEKH SHARMA SHIVNARAYAN SHARMA VPO-KARUNDA, TEH-CHHOTI SADRI 7 ADITI MEHAR KAILASH CHANDRA MEHAR RAJPUT MOHALLA BIJOLIYA 8 ADITYA DAVE DEEPAK KUMAR DAVE DADAI ROAD VARKANA 9 ADITYA DIXIT SHYAM SUNDER DIXIT BHOLE NATH IRON, BHAGWAN DAS MARKET, JALCHAKKI ROAD, KANKROLI 10 AHIR JYOTI SHANKAR LAL SHANKAR LAL DEVIPURA -II, TEH-RASHMI 11 AJAY KUMAR MEENA JEEVA JI MEENA VILLAGE KODIYA KHET POST BARAPAL TEH.GIRWA 12 AJAY KUMAR SEN SURESH CHANDRA SEN NAI VILL- JAISINGHPURA, POST- MUNJWA 13 AKANSHA SINGH RAO BHAGWAT SINGH RAO 21, RESIDENCY ROAD, UDAIPUR 14 AKASH KUMAR MEENA BHIMACHAND MEENA VILL MANAPADA POST KARCHA TEH KHERWARA 15 AKSHAY KALAL LAXMAN LAL KALAL TEHSIL LINK ROAD VPO : GHATOL 16 AKSHAY MEENA SHEESHPAL LB 57, CHITRAKUT NAGAR, BHUWANA, UDAIPUR (RAJ.) - 313001 17 AMAN KUSHWAH UMA SHANKER KUSHWAH ADARSH COLONY KAPASAN 18 AMAN NAMA BHUPENDRA NAMA 305,INDRA COLONEY RAILWAY STATION MALPURA 19 AMBIKA MEGHWAL LACHCHHI RAM MEGHWAL 30 B VIJAY SINGH PATHIK NAGAR SAVINA 20 AMISHA PANCHAL LOKESH PANCHAL VPO - BHILUDA TEH - SAGWARA 21 ANANT NAI RAJU NAI ANANT NAI S/O RAJU NAI VPO-KHODAN TEHSIL-GARHI 22 ANIL JANWA JAGDISH JANWA HOLI CHOUK KHERODA TEH VALLABHNAGAR 23 ANIL JATIYA RATAN LAL JATIYA VILL- JATO KA KHERA, POST- LAXMIPURA 24 ANIL YADAV SHANKAR LAL YADAV VILL-RUNJIYA PO-RUNJIYA 25 ANISHA MEHTA ANIL MEHTA NAYA BAZAAR, KANORE DISTT. -

Ground Water Scenario Baran District

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER SCENARIO BARAN DISTRICT WESTERN REGION JAIPUR 2013 GROUND WATER SCENARIO BARAN DISTRICT S. No. Item Information 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical area (sq. km) 6955.31 Administrative Divisions a. No. of tehsils / blocks 08/07 b. No. of villages 1114 inhabited 126 non habited c. No. of towns 4 d. No. of municipalities 4 Population (as per 2011 census) 1222755 Average annual rainfall (mm) (2001 - 707 2011) 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographical Units Hill ranges of Vindhyans in the northeast and low rounded hills of Malwa plateau in the south bound the region. Sedimentary rocks of Vindhyan Supergroup occupy northwestern part. Major Drainage The drainage system is well developed and represented by Chambal, which is perennial in nature. 3. LAND USE (ha) (2010-11) Forest area 216494 Net sown area 338497 Cultivable area (net sown area + 366348 fallow land) 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES 1. Deep black clayey soil 2. Deep brown loamy soil 3. Red gravelly loam hilly soil 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS (ha) (2010-11) Food grains Bajra : 3472 Jowar : 2006 Wheat : 147930 Barley : 559 Rice : 8231 Maize : 16913 Total Pulses 10872 Total Oil seeds 311473 Total Condiments & Spices 67818 6. IRRIGATI ON BY DIFFERENT Net Area irrigated Gross area SOURCES (ha) irrigated Canal 54485 57488 S. No. Item Information Tank 2376 3137 Tubewells 191558 200258 Other wells 28252 28293 Other sources 16052 16820 Total 292723 306626 7. NUMBER OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB No. of dug wells 20 No. of piezometers 1 8. PREDOMINENT GEOLOGICAL Upper Vindhyan, Bhander Group, FORMATIONS Ganurgarh shales, Bhander limestone and Bhander sandstone overlain by Deccan traps and alluvium of Quaternary age. -

Sustainable Water Management Practices: Addressing a Water Scarcity Crisis in Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

1 Sustainable Water Management Practices: Addressing a Water Scarcity Crisis in Jaipur, Rajasthan, India View from Jaigarh Fort - Jaipur, Rajasthan. February 2019. Photo by Author Kira Baltutis University of Illinois at Chicago | Master’s in Urban Planning and Policy Email: [email protected] 2 Abstract Although urbanization often drives development and brings potential for prosperity, it also presents significant social, economic and environmental challenges that can exacerbate existing issues among populations experiencing growth. The expansion of urban and peri-urban communities, coupled with climate change, has led to the depletion (and often contamination) of existing water resources that pose grave challenges to the future of our planet’s inhabitants. This report focuses on the crucial role of water supply to residents in the rapidly growing city of Jaipur, situated in the arid state of Rajasthan, India, which has a population of 3.1 million per India’s 2011 census and an annual growth rate of 3%. Water scarcity has become an ongoing headline issue in Jaipur as household access to government-supplied piped water has been limited to approximately one hour a day between the hours of 6:00 and 7:00 a.m., giving residents just enough time to fill up any water storage containers for all daily needs. For people living in freshwater-rich regions with unlimited access to clean water, this can be a nearly unfathomable way of life. To explore the myriad implications of this phenomenon at the community level, I conducted a 10-day long immersive fieldwork in Jaipur between January and February 2019. Through community member interviews and observational research in six key locations throughout the city of Jaipur and Amer, an adjoining historic settlement, I use both personal experiences and verified data to examine the challenges Jaipur faces to provide a clean, affordable, and consistent water supply to its expanding population. -

Circle District Location Acc Code Name of ACC ACC Address

Sheet1 DISTRICT BRANCH_CD LOCATION CITYNAME ACC_ID ACC_NAME ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3091004 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA 5849/22 LAKHAN KOTHARI CHOTI OSWAL SCHOOL KE SAMNE AJMER RA9252617951 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3047504 RAKESH KUMAR NABERA 5-K-14, JANTA COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR, AJMER, RAJASTHAN. 305001 9828170836 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3043504 SURENDRA KUMAR PIPARA B-40, PIPARA SADAN, MAKARWALI ROAD,NEAR VINAYAK COMPLEX PAN9828171299 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002204 ANIL BHARDWAJ BEHIND BHAGWAN MEDICAL STORE, POLICE LINE, AJMER 305007 9414008699 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3021204 DINESH CHAND BHAGCHANDANI N-14, SAGAR VIHAR COLONY VAISHALI NAGAR,AJMER, RAJASTHAN 30 9414669340 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3142004 DINESH KUMAR PUROHIT KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9413820223 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3201104 MANISH GOYAL 2201 SUNDER NAGAR REGIONAL COLLEGE KE SAMMANE KOTRA AJME 9414746796 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3002404 VIKAS TRIPATHI 46-B, PREM NAGAR, FOY SAGAR ROAD, AJMER 305001 9414314295 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3204804 DINESH KUMAR TIWARI KALYAN KUNJ SURYA NAGAR DHOLA BHATA AJMER RAJASTHAN 30500 9460478247 [email protected] Ajmer RJ-AJM AJMER Ajmer I rj3051004 JAI KISHAN JADWANI 361, SINDHI TOPDADA, AJMER TH-AJMER, DIST- AJMER RAJASTHAN 305 9413948647 [email protected] -

Jaipur Development Plan 2025

MASTER DEVELOPMENT PLAN-2025 JAIPUR REGION Volume-2 DEVELOPMENT PLAN-2025 Jaipur Region Jaipur City JAIPUR DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY PREFACE olume-I outlined the existing profile and volume-II attends to the Vfollowing with two front approaches Projections based on the existing studies Requirements spread and spatial distribution The Master Development Plan-2025 covers all aspects of development including transportation, infrastructure (sewer, drainage, water and electricity), environmental protection, and land uses (residential, commercial, industrial, recreational, etc.). The Master Plan analyzes current demographic statistics and economic issues, factors to project growth scenarios, propose solutions that mitigate negative impacts of traffic, assess infrastructure capacity, and public service needs, and allocate land as needed to ensure adequate land availability and to be able to utilize them for both present and future needs of the residents. Volume-I consist of existing profile of Jaipur district, Jaipur region and U1 area and the collected data has been used for analysis which would act as base for projections and proposals. Volume-I enumerate the following chapters: 1. Background 2. Jaipur District profile 3. Jaipur Region 4. Jaipur U1 area 5. Quality of Life District level study and conclusions are given in Jaipur District Profile chapter of volume-1 while projection and proposals for Jaipur Region and U- 1 area have been made separately give in volume -2. Planning proposal for Jaipur Region and U-1 area are based on background study of volume-1. volume-2 "Development Plan" is the second part of MDP-2025 which enumerates following : 1. Projections and proposals for Jaipur region 2. Proposals for U1 area 3. -

04 Delhi / Jaipur / Agra / Delhi TOUR SCHEDULE

MAHATMA GANDHI MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND GANDHI 2 October 1869 - 30 January 1948 PROGRAM- 04 Delhi / Jaipur / Agra / Delhi TOUR SCHEDULE Day 01 Arrive Delhi Upon arrival, after clearing immigration and custom, you will be met and transferred to your hotel. (Check-in at 1200hrs) Overnight at hotel / Home Stay Day 02 Delhi Following breakfast, Full day city tour of Old & New Delhi Old Delhi: Visit Raj Ghat, National Gandhi museum (Closed on Mondays), Old Delhi Here you will drive past Red Fort, the most opulent Fort and Palace of the Mughal Empire: Raj Ghat, the memorial site of the Mahatma Gandhi, Jama Masjid, the largest mosque in India and Chandni Chowk, the bustling and colourful market of the old city (Red Fort Closed on Mondays) Afternoon, visit New Delhi. Gandhi Smriti formerly known as Birla House or Birla Bhavan, is a museum dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi, situated on Tees January Road, formerly Albuquerque Road, in New Delhi, India. It is the location where Mahatma Gandhi spent the last 144 days of his life and was assassinated on 30 January 1948. It was originally the house of the Indian business tycoons, the Birla family. It is now also home to the Eternal Gandhi Multimedia Museum, which was established in 2005. The museum is open for all days except Mondays and National Holidays Visits to such sights Humayun’s Tomb (1586): Built in the mid-16th century by Haji Begum, wife of Humayun, the second Moghul emperor, this is an early example of Moghul architecture. The elements in-'tte design — a squat building, lightened by high arched entrances, topped by a bulbous dome and surrounded by formal gardens — were to be refined over the years to the magnificence of the Taj Mahal in Agra. -

List of Private Empaneled Hospitals S.N

List of Private Empaneled Hospitals S.N. District Hosp_Code Hospital Name Address H_INCHARGE Name MOBILE NO. Email _Id 1 AJMER Ajme386 ANAND MULTISPECIALITY & RESEARCH GOVINDPURA, JALIYA ROAD, JODHPUR DR. NARENDRA 9269625000 [email protected], CENTER BYE PASS, BEAWAR ANANDANI 2 AJMER Ajme1226 DEEPMALA PAGARANI HOSPITAL & 76-A, INSIDE SWAMI MADHAV DWAR, DR. JAWAHAR LAL 0145-2445445, [email protected], RESEARCH CENTRE ADARSH NAGAR GARGIYA 9414444491, 9414148424 3 AJMER Ajme1650 DR KHUNGER EYE CARE HOSPITAL OPP PNB BANK DR. NEERAJ KHUNGER 0145-2442000, [email protected] 9982537977, 9829070265 4 AJMER Ajme1882 DR VIJAY ENT HOSPITAL 58 59 MAKARWALI ROAD ST STEPHEN DR.VIJAY GAKHAR 9982147067 [email protected] CIRCLE VAISHALI NAGAR AJMER 5 AJMER Ajme168 JMD HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE HIGHWAY COLONY, BEAWAR DR. ASHA KHANNA 01462-252290, [email protected], 9829071475 6 AJMER Ajme821 KHETRAPAL HOSPITAL SECTOR C, PANCHSHEEL NAGAR ALOK SHARMA 0145-2970501, [email protected], MULTISPECIALITY & RESEARCHJ CENTRE 9116010913 7 AJMER Ajme1799 MARBLE CITY HOSPITAL KISHANGARH ANKIT SHARMA 9694090058 [email protected] 8 AJMER Ajme1144 MEWAR HOSPITAL PVT LTD A-175, HARI BHAU UPADHYAY NAGAR SAIF MOIN 0145-2970188, [email protected], MAIN, NEAR GLITZ CINEMA 7727009307 9 AJMER Ajme1316 MITTAL HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER PUSHKAR ROAD YUVRAJ PARASHAR 9351415247 [email protected], 10 AJMER Ajme1653 PUSHPA CHANDAK MEMORIAL BANGALI GALI, KUTCHERY ROAD DR. LAXMI NIWAS 0145-2626208, [email protected], MULTISPECIALITY HOSPITAL CHANDAK 9829087032 11 AJMER Ajme822 RATHI HOSPITAL AJMER ROAD, KISHANGARH DR. SANJAY RATHI 01463-247050, [email protected], 9166915452 12 AJMER Ajme1694 SHREE PARSHVNATH JAIN HOSPITAL UDAIPUR ROAD,BEAWAR DR NM SINGHVI 01462-223351, [email protected] AND RESEARCH CENTER 9414277764 13 AJMER Ajme1401 SHREE PKV (PRAGYA KUNDAN BEAWAR ROAD, BIJAINAGAR DR.