RIT Scholar Works Scapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae 2017

Thierry de Duve 650 W 42nd Street, # 2306 New York, NY 10036 USA Mobile: 213-595-6869 [email protected] U.S. citizen Married to artist Lisa Blas Curriculum Vitae Education - 1994: Habilitation à diriger des recherches (sur travaux), Université de Rennes 2. - 1981: PhD in “Sociologie et sémiologie des arts et littératures”, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris. Dissertation directed by Prof. Louis Marin: Une sorte de Nominalisme pictural, Essai sur un passage et une transition de Marcel Duchamp, peintre. (Jury: Profs. Jean- François Lyotard, Louis Marin, Christian Metz). - 1972: Masters degree in Psychology, University of Louvain, Belgium. Thesis subject: Prolégomènes à une sémiotique de l’espace pictural. - 1972: Bachelor degree in Philosophy, University of Louvain. - 1962-1965: Industrial Design studies at the Institut Supérieur St Luc in Liège, Belgium (1962- 1963), and at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, W. Germany (1963-1965). Teaching activities: tenured positions - 2015-: Evelyn Kranes Kossak Professor and Distinguished Lecturer, Department of Art and Art History, Hunter College, CUNY, New York. - 2003-2012: Full Professor, Université Lille 3, Département Arts plastiques. Emeritus Sept. 2012. - 1991-1993: Directeur des études (Director of Studies), Association de préfiguration de l’Ecole des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris. In charge of the pedagogical structure and program of the future school. For political and economic reasons, the project was terminated on 1st January 1994. - 1982-91: Associate Professor at the University of Ottawa, Departement of Visual Arts. Tenure obtained in January 1984. - 1972-81: Professor at the Institut Supérieur St Luc, Brussels, Department of Visual Arts. -

A FUND for the FUTURE Francis Alÿs Stephan Balkenhol Matthew

ARTISTS FOR ARTANGEL Francis Alÿs Stephan Balkenhol Matthew Barney Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller Vija Celmins José Damasceno Jeremy Deller Rita Donagh Peter Dreher Marlene Dumas Brian Eno Ryan Gander Robert Gober Nan Goldin Douglas Gordon Antony Gormley Richard Hamilton Susan Hiller Roger Hiorns Andy Holden Roni Horn Cristina Iglesias Ilya and Emilia Kabakov Mike Kelley + Laurie Anderson / Kim Gordon / Cameron Jamie / Cary Loren / Paul McCarthy / John Miller / Tony Oursler / Raymond Pettibon / Jim Shaw / Marnie Weber Michael Landy Charles LeDray Christian Marclay Steve McQueen Juan Muñoz Paul Pfeiffer Susan Philipsz Daniel Silver A FUND FOR THE FUTURE Taryn Simon 7-28 JUNE 2018 Wolfgang Tillmans Richard Wentworth Rachel Whiteread Juan Muñoz, Untitled, ca. 2000 (detail) Francis Alÿs Stephan Balkenhol Matthew Barney Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller Vija Celmins José Damasceno Jeremy Deller Rita Donagh Peter Dreher Marlene Dumas Brian Eno ADVISORY GROUP Ryan Gander Hannah Barry Robert Gober Erica Bolton Nan Goldin Ivor Braka Douglas Gordon Stephanie Camu Antony Gormley Angela Choon Richard Hamilton Sadie Coles Susan Hiller Thomas Dane Roger Hiorns Marie Donnelly Andy Holden Ayelet Elstein Roni Horn Gérard Faggionato LIVE AUCTION 28 JUNE 2018 Cristina Iglesias Stephen Friedman CONDUCTED BY ALEX BRANCZIK OF SOTHEBY’S Ilya and Emilia Kabakov Marianne Holtermann AT BANQUETING HOUSE, WHITEHALL, LONDON Mike Kelley + Rebecca King Lassman Laurie Anderson / Kim Gordon / Prue O'Day Cameron Jamie / Cary Loren / Victoria Siddall ONLINE -

Press Release

Press Release Whitney Museum of American Art Contact: 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street Whitney Museum of American Art New York, NY 10021 Stephen Soba, Leily Soleimani whitney.org/press 212-570-3633 Tel. (212) 570-3633 Fax (212) 570-4169 [email protected] A FEW FRAMES: PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE CONTACT SHEET OPENS AT THE WHITNEY September 25, 2009–January 3, 2010 David Wojnarowicz (1954–92), Untitled, 1988. Synthetic polymer on two chromogenic prints, 11 x 13 1/4 in. (27.9 x 33.7 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee 95.88. Courtesy of The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York, NY New York, September 24, 2009 — In this selection of works drawn principally from the Whitney’s permanent collection, the repetitive image of the proof sheet is the leitmotif in a variety of works spanning the range of the museum’s photography collection, including the works of Paul McCarthy, Robert Frank, Ed Ruscha, and Andy Warhol. The exhibition is co-curated by Elisabeth Sussman, Whitney Curator and Sondra Gilman Curator of Photography, and Tina Kukielski, Senior Curatorial Assistant. A Few Frames opens on September 25, 2009 in the Sondra Gilman Gallery and runs through January 3, 2010. Decisions about which photograph to exhibit or print are frequently the end result of an editing process in which the artist views all of the exposures he or she has made on a contact sheet—a photographic proof showing strips or series of film negatives— and then selects individual frames to print or enlarge. -

Dan Graham to Be Presented at Whitney, June 25-October 11, 2009

Press Release Whitney Museum of American Art Contact: 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street Whitney Museum of American Art New York, NY 10021 Stephen Soba, Leily Soleimani whitney.org/press 212-570-3633 Tel. (212) 570-3633 Fax (212) 570-4169 [email protected] RETROSPECTIVE OF PIONEERING ARTIST DAN GRAHAM TO BE PRESENTED AT WHITNEY, JUNE 25-OCTOBER 11, 2009 Dan Graham performing Performer/Audience/Mirror at P.S.1 Institute for Contemporary Art, Long Island City, NY, 1977. Photo courtesy of the artist. NEW YORK, March 26, 2009 -- Dan Graham, one of the pioneering figures of contemporary art, is the subject of a landmark retrospective opening at the Whitney Museum of American Art on June 25. Dan Graham: Beyond is the first-ever comprehensive museum survey of Graham’s career to be done in the United States. The show is co-curated by Chrissie Iles, the Whitney’s Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Curator, and Bennett Simpson, MOCA associate curator. Organized by The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, in collaboration with the Whitney, it examines Graham’s extensive body of work in photographs, film and video, architectural models, indoor and outdoor pavilions, conceptual projects for magazine pages, drawings, prints, and writings. Dan Graham: Beyond is the latest in a trio of collaborations between the Whitney and MOCA, following Gordon Matta-Clark: You Are the Measure and Lawrence Weiner: As Far As the Eye Can See, celebrating the work of three major figures in American art, each of whom emerged in the 1960s. Following its presentation at the Whitney from June 25 to October 11, 2009, the Graham exhibition travels to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, from October 31, 2009 to January 31, 2010. -

A Vocabulary of Water: How Water in Contemporary Art Materialises the Conditions of Contemporaneity

A VOCABULARY OF WATER HOW WATER IN CONTEMPORARY ART MATERIALISES THE CONDITIONS OF CONTEMPORANEITY Tessa Elisabeth Fluence Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne March 2015 ABSTRACT This thesis provides an in-depth analysis of how water in three contemporary artworks provides an affective vocabulary that gives material expression to the forces and dynamics that shape our current era. It argues water is not simply a medium or metaphor; in the artworks, it articulates and is symptomatic of the conditions of contemporaneity. Focusing on the dynamics of time, placemaking and identity, it argues water in the artworks makes present our era’s fluid, multiple, precarious, contingent, complex, disorientating, immersive and overwhelming nature. This dissertation uses Terry Smith’s theory of contemporaneity as a lens through which to identify the dynamics and forces of this era. By focusing on water in three artworks, it amplifies and extends his work to consider how the particular vocabulary of water materialises these forces. This is demonstrated through three case studies of exemplary artworks in different mediums, made between 2000 and 2004, by Zhu Ming, Roni Horn and Bill Viola. Drawing on Mieke Bal’s approach of conceptual travelling, I do a close reading of each artwork, orchestrating a conversation between the work, the concept of water and the theory of contemporaneity. Focusing on the role of water in each work, I argue water provides a potent comment on the conditions of contemporaneity, offering a new ontology that is appropriate to, and symptomatic of, today’s complex conditions. -

Galleria Raffaella Cortese Roni Horn

galleria raffaella cortese roni horn MONOGRAPHS & EXHIBITION CATALOGUES 2019 White, Michelle, Roni Horn. When I Breathe, I Draw, Houston: The Menil Collection, 2019 2018 Carroll, Henry, Photographers on Photography. How the Masters See, Think & Shoot, London: Laurence King Publishing Ltd., 2018, pp. 60, 89, ill. Fer, Briony, Roni Horn. Dog’s Chorus, Göttingen: Steidl Verlag, 2018 Lauson, Cliff, Schuld, Dawna + [et al.], Space Shifters, London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 2018, pp. 82- 89, ill. in colour (exh. cat.) Molesworth, Helen, One Day at a Time. Manny Farber and Termite Art, Los Angeles: The Museum of Modern Art Los Angeles, Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2018, pp. 114-117, ill. in colour (exh. cat.) Poivert, Michel, La Photographie Contemporaine, Paris: Flammarion, 2018, p. 57, ill. in colour (detail) Larrat-Smith, Philip, That Obscure Object of Desire, São Paulo/BR: Galeria Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, 2018, ill. (catalogue) Aloi, Giovanni, Speculative Taxidermy: Natural History, Animal Surfaces and Art in the Antrhopocene, New York NY: Columbia University Press, 2018, ill. (catalogue) Chao, Marina, Williams, Stephanie Sparling + [et. al.], Multiply, Identify, Her, New York: International Center of Photography, 2018. 2017 Horn, Roni, 82 Postcards, Zurich: Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2017 Horn Roni, Roni Horn. Th Rose Prblm, Göttingen: Steidl Verlag, 2017 Wei Rales, Emily, Nemerov, Ali, Roni Horn, Potomac MD: Glenstone Museum and Del Monico Books/ Prestel, 2017 (catalogue) 2016 Allred, Ry (ed.), Collected, Sand Francisco CA: Pier 24 Photography, 2016, pp. 96-97, ill. in colour (catalogue) Hoffmann, Jens (ed.), Animality. A Fairy Story, New York/Hoek van Holland: Marian Goodman Gallery/ Unicum, 2016, pp. 78-80, ill. -

Roni Horn October 2, 2016 – January 1, 2017

Media Release Roni Horn October 2, 2016 – January 1, 2017 The exhibition by American artist Roni Horn (*1955 in New York) features outstanding groups of works and series she has created over the last twenty years. The photographic installations, works on paper, and sculptures made of cast glass displayed in the six rooms devoted to the show can be experienced as a coherent installation. The exhibition “Roni Horn” has been developed in close cooperation with the artist for the space at the Fondation Beyeler. Several new works are being presented for the first time. Roni Horn’s art focuses on the idea of identity and mutability. In her works, Horn succeeds in subtly exploring fixed attributions and in emphasizing ephemerality and diversity. They show how the essence of things can differ from their visual appearance. It is therefore no coincidence that she uses materials like glass or subjects like water or weather, which are multifaceted and have a form and natural state that are subject to change. Her ideas take on visible forms centered on the experiences they enable. Her playful approach to language and literature endows the images she creates with an even broader range of meaning. Roni Horn has travelled regularly to Iceland since 1975. The uniquely rugged landscape, the extremely changeable weather conditions, and the country’s remoteness are her main sources of inspiration: “Big enough to get lost on. Small enough to find myself.” The curator of the exhibition is Theodora Vischer, Senior Curator at the Fondation Beyeler. The “Roni Horn” exhibition is being supported by: Beyeler-Stiftung Hansjörg Wyss, Wyss-Foundation Helen and Chuck Schwab Press images: are available for download at http://pressimages.fondationbeyeler.ch Further information: Elena DelCarlo, M.A. -

Roni Horn – Water Teller Peder Lund Is Proud to Present the Exhibition

Roni Horn – Water Teller Peder Lund is proud to present the exhibition “Water Teller” by the American artist Roni Horn, comprising two glass sculptures and a new photographic series. The exhibition opens 22 November 2014 and will be on view through 24 January 2015. For more than 30 years, Roni Horn (1955- ) has worked with a wide range of media, ranging from photography, draw- ing, sculptural installations and performance, to artist’s books and text. Horn’s work concerns matters such as the mutable nature of identity and that of the natural world, and the relationship between subject and object in perception of art and nature. Across the multidisciplinary formal approaches she has employed throughout her oeuvre, Horn has remained focused and her subject matters well articulated. Horn graduated with an MFA from Yale University in 1978, and had her first solo exhibition at Kunstraum in Munich in 1980. Shortly after, Horn travelled to Iceland where she traversed the country on a motorbike. Iceland became an important source of inspiration for Horn, and her continuous travels there have had a significant influence on her art. Between 1994 and 1996, Horn produced the photographic series “You Are The Weather,” which is made up of 64 photographs of a young woman’s face as she is bathing in various Icelandic hot springs in different weather conditions. Horn has also published a number of artist’s books in which she reflects on her relationship to Iceland. The exhibition “Water Teller” presents Horn’s multifaceted practice by touching on themes including the artist’s abid- ing interest in water, and her recurrent formal device of doubling and pairing. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Between Motion and Stasis A Thesis Presented by Hronn Axelsdottir to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art Stony Brook University August 2011 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Hronn Axelsdottir We, the thesis committee for the above candidate for the Master of Fine Arts degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this thesis. Stephanie Dinkins – Thesis Advisor Associate Professor Studio Art Andrew Uroskie – Second Reader Assistant Professor Art History and Criticism Nobuho Nagasawa– Third Reader Professor Studio Art This thesis is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Thesis Between Motion and Stasis by Hronn Axelsdottir Master of Fine Arts in Studio Art Stony Brook University 2011 This thesis is about my progress from photography to video installation. There is an exploration of my use of material, such as light, porcelain, photography and video and the importance of the screen with the pieces. While discussing the use of the screen, attention is paid to the process of using photography and how it evolved from photography to video. There is also a discussion of my progress from thinking two dimensionally within the space, one point perspective of the image, going towards the expansion of the work into the space. Although the work has evolved from photography to video there is a continued interaction between the still and the moving image in my work. -

READING AS SCULPTURE: RONI HORN and EMILY DICKINSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the De

READING AS SCULPTURE: RONI HORN AND EMILY DICKINSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Eva Heisler, M.A. The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Stephen Melville, Advisor Professor J. Ronald Green Professor Barbara Groseclose Adviser Graduate Program in History of Art ABSTRACT The United States sculptor Roni Horn has produced four bodies of work that present lines from Emily Dickinson as aluminum columns and cubes: How Dickinson Stayed Home (1992-3); When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes (1993); Keys and Cues (1994); and Untitled (Gun) (1994). This dissertation examines Horn’s Dickinson-objects within the context of twentieth century sculpture as well as within the context of debates surrounding the material and conceptual circumference of the Dickinson poem—in particular the new privileging of the visual in the Dickinson manuscript—and the emergence of text-based art that positions the viewer as a reader and raises questions about the dislocation of the visual in contemporary art. It is argued that Horn’s Dickinson-objects harness the syntactical demands of the Dickinson lyric in the service of the artist’s preoccupation with temporal experience and the demands of sculpture. Each of the dissertation’s four chapters is centered around one work in Horn’s Dickinson series and discusses the work in terms of both Dickinson studies and the history of sculpture. Chapter One considers the installation How Dickinson Stayed Home and examines circumference as both theme and artistic strategy in Dickinson’s work followed by a discussion of the dialectical relationship between center and circumference enacted by the work of Robert ii Smithson and Richard Serra. -

Photobooks After Frank

From the Library: Photobooks after Frank August 8, 2015 – February 7, 2016 National Gallery of Art Robert Frank, detail from The Americans (1) From the Library: Photobooks after Frank The term photobook was coined to describe a specific book format that uses photographs as a substantial part of the overall content. In recent years, interest in this method of presentation — as distinct from other photographic practices — has increased. Of course, books and photography have been linked almost since the moment of photography’s invention. There have been many important and influential books of photographs, but Robert Frank’s masterpiece The Americans, which appeared in the late 1950s, was partic- ularly significant. The fluid, instantaneous aesthetic present in this work paved the way for social landscape photography and its practitioners, such as Garry Winogrand and Danny Lyon. Eventually other photographers like William Eggleston took this style further and began working in color, leading to color photography’s transcendence of the com- mercial and advertising worlds to find acceptance in the fine-art world. Frank’s stream-of- consciousness approach, a diary of subjective truth, helped both to expand the possibili- ties of photography beyond objective documentation — which had come to dominate the field in the 1930s and early 1940s — and also to further the acceptance of photography as an appropriate art form for personal expression. The serial presention of photogaphs in a codex, while certainly not new, was so skillfully executed in The Americans that the volume became a handbook for following generations and elevated the monograph to the same level as the magazine photo-essay that had grown in popularity since the end of World War II. -

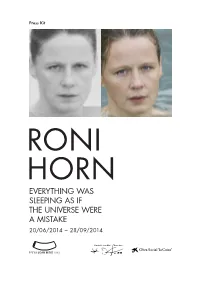

Everything Was Sleeping As If the Universe Were a Mistake 20/06/2014 – 28/09/2014

Press Kit EVERYTHING WAS SLEEPING AS IF THE UNIVERSE WERE A MISTAKE 20/06/2014 – 28/09/2014 Index 1. General information 3 2. Press release 4 3. Jury statement 8 4. Biography of Roni Horn 9 5. Room plan 11 6. List of works 12 7. Practical information 18 2 1. General information Roni Horn. Everything was sleeping as if the universe were a mistake 20 June – 28 September 2014 Press conference: 18 June at 12.00 Opening: 19 June at 19.30 Exhibition organised by Fundació Joan Miró ”la Caixa” Foundation Catalogue Fundació Joan Miró and ”la Caixa” Foundation Main text: Julie Ault in conversation with Roni Horn Editions in Catalan, Spanish and English 3 2. Press release The Fundació Joan Miró and Obra Social ”la Caixa” present the exhibition Roni Horn. Everything was sleeping as if the universe were a mistake. In her first monographic exhibition in Barcelona, Roni Horn uses her work to question the reality that surrounds her, her own identity, and her relationship with the environment. The works in the show include her latest sculptural installation, which has only been shown once before at Hauser & Wirth gallery in New York. Roni Horn is the winner of the fourth edition of the Joan Miró Prize, a biennial award bestowed by the Fundació Joan Miró and Obra Social ”la Caixa”, which includes a cash prize of 70,000 euros and an invitation to exhibit her work in 2014. The exhibition Roni Horn. Everything was sleeping as though the universe were a mistake is organised by the Fundació Joan Miró and Obra Social ”la Caixa”.