PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration. Metaarxiv Preprint (September 2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen P. Lock on "Journalology"

INSTITUTE FOn SCIENTl FICl NF0F4MAT10N8 3501 MARKET ST PHILADELPHIA PA 19104 Stephen P. Lock on “Journalology” Number 3 January 15, 1990 I don’t remember exactly how long I have Lock: Editor and Scholar known Stephen P. Lock. Our first encounter was probably at a meeting of the Council of Biology Editors (CBE) some 20 years Stephen P. Lock was born in 1929 and re- ago. It is somewhat unsettling to realize that ceived his education at Queen’s College, so much time has gone by. Equally disquiet- Cambridge University, UK, and the Medical ing is the notion that Steve will soon retire College of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. as editor of the venerable British Medical Trained as a hematologist, he served on the Journal (BMJ). But in the near future Steve staffs of various London teaching hospitals, will indeed step down, having helped train including St. Bartholomew’s and the Hos- his successor, due to be appointed in the fall pital for Sick Children, before being ap- of 1990. pointed assistant editor of BMJ in 1964. It seems odd to refer to Lock as an elder After serving as senior assistant editor and statesman of biomedical editing-however deputy editor, Lock became editor in 1975. accurate that description might be. The word I am amused that Steve opened his talk that comes to mind when I think of Steve with the traditional, mythical reminder about is youth. This youthfidness is reflected in the estimates of the number of extant jour- his writing and in his approach to problems. nals. -

Evidence Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians

Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians Workbook Harris C & Turner T 2011 Updated 2018 This publication should be cited as: Harris C & Turner T. Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians. (2011) The Centre for Clinical Effectiveness, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia. Copyright © This publication is the copyright of Monash Health. Other than for the purposes and subject to the conditions prescribed under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part of this publication may, in any form or by any means (electric, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise), be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to Centre for Clinical Effectiveness. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge past and present staff of the Centre for Clinical Effectiveness at Monash Health for their contributions towards the development of this resource. Centre for Clinical Effectiveness Monash Health Phone: +61 3 9594 7575 Fax: +61 3 9594 6018 Email: [email protected] Web : www.monashhealth.org/cce Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions for Busy Clinicians Workbook 2 Objectives This workbook aims to help you to find the best available evidence to answer your clinical questions, in the shortest possible time. It will introduce the principles of evidence-based practice and provide a foundation of understanding and skills in: o Developing questions that are answerable from the literature o Searching for and identifying evidence to answer your question o Appraising the evidence identified for quality, reliability, accuracy and relevance Contents page 1. What is evidence-based practice? 4 2. -

Assessing the Utility of an Institutional Publications Officer: a Pilot Assessment

Assessing the utility of an institutional publications officer: a pilot assessment Kelly D. Cobey1,2,3, James Galipeau1, Larissa Shamseer1,2 and David Moher1,2 1 Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada 2 School of Epidemiology, Public Health, and Preventative Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada 3 School of Natural Sciences, Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, Stirling, United Kingdom ABSTRACT Background. The scholarly publication landscape is changing rapidly. We investigated whether the introduction of an institutional publications officer might help facilitate better knowledge of publication topics and related resources, and effectively support researchers to publish. Methods. In September 2015, a purpose-built survey about researchers' knowledge and perceptions of publication practices was administered at five Ottawa area research institutions. Subsequently, we publicly announced a newly hired publications officer (KDC) who then began conducting outreach at two of the institutions. Specifically, the publications officer gave presentations, held one-to-one consultations, developed electronic newsletter content, and generated and maintained a webpage of resources. In March 2016, we re-surveyed our participants regarding their knowledge and perceptions of publishing. Mean scores to the perception questions, and the percent of correct responses to the knowledge questions, pre and post survey, were computed for each item. The difference between these means or calculated percentages was then examined across the survey measures. Results. 82 participants completed both surveys. Of this group, 29 indicated that they had exposure to the publications officer, while the remaining 53 indicated they did not. Interaction with the publications officer led to improvements in half of the knowledge items (7/14 variables). -

Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child with a Co-Occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder

Volume 8, Issue 6 March 2014 EBP briefs A scholarly forum for guiding evidence-based practices in speech-language pathology Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child With a Co-occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder Keegan M. Koehlinger Linda Louko Patricia Zebrowski EBP Briefs Editor Laura Justice The Ohio State University Associate Editor Mary Beth Schmitt The Ohio State University Editorial Review Board Tim Brackenbury Lisa Milman Bowling Green State University Utah State University Jayne Brandel Cynthia O’Donoghue Fort Hays State University James Madison University Kathy Clapsaddle Amy Pratt Private Practice (Texas) The Ohio State University Lynn Flahive Nicole Sparapani Texas Christian University Florida State University Managing Director Tina Eichstadt Pearson 5601 Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN 55437 Cite this document as: Koehlinger, K. M., Louko, L., & Zebrowski, P. (2014). Application of the PICO process to plan treatment for a child with a co-occurring stuttering and phonological disorder. EBP Briefs, 8(6), 1–9. Bloomington, MN: Pearson. Copyright © 2014 NCS Pearson, Inc. All rights reserved. Warning: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the express written permission of the copyright owner. Pearson, PSI design, and PsychCorp are trademarks, in the US and/or other countries, of Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliate(s). NCS Pearson, Inc. 5601 Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN 55437 800.627.7271 www.PearsonClinical.com Produced in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 A B C D E Application of the PICO Process to Plan Treatment for a Child With a Co-occurring Stuttering and Phonological Disorder Keegan M. -

Core Competencies for Scientific Editors Of

Moher et al. BMC Medicine (2017) 15:167 DOI 10.1186/s12916-017-0927-0 CORRESPONDENCE Open Access Core competencies for scientific editors of biomedical journals: consensus statement David Moher1,2* , James Galipeau3, Sabina Alam4, Virginia Barbour5, Kidist Bartolomeos6, Patricia Baskin7,8, Sally Bell-Syer9,10, Kelly D. Cobey1,2,11, Leighton Chan12, Jocalyn Clark13, Jonathan Deeks14, Annette Flanagin15, Paul Garner16, Anne-Marie Glenny17, Trish Groves18, Kurinchi Gurusamy19, Farrokh Habibzadeh20,21,22, Stefanie Jewell-Thomas23, Diane Kelsall24, José Florencio Lapeña Jr22,25,26,27, Harriet MacLehose28, Ana Marusic29,30, Joanne E. McKenzie31, Jay Shah32,33,34, Larissa Shamseer1,2, Sharon Straus35, Peter Tugwell2,36,37, Elizabeth Wager38,39, Margaret Winker22 and Getu Zhaori40 Abstract Background: Scientific editors are responsible for deciding which articles to publish in their journals. However, we have not found documentation of their required knowledge, skills, and characteristics, or the existence of any formal core competencies for this role. Methods: We describe the development of a minimum set of core competencies for scientific editors of biomedical journals. Results: The 14 key core competencies are divided into three major areas, and each competency has a list of associated elements or descriptions of more specific knowledge, skills, and characteristics that contribute to its fulfillment. Conclusions: We believe that these core competencies are a baseline of the knowledge, skills, and characteristics needed to perform competently the duties of a scientific editor at a biomedical journal. Keywords: Core competencies, Scientific editor, Biomedical journal, Delphi, Expert consensus, Editor role Introduction and in guidance for members of editor organizations Scientific editors (editors are responsible for the content [3–8]. -

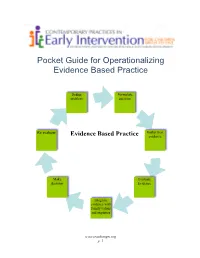

Pocket Guide for Operationalizing Evidence Based Practice

Pocket Guide for Operationalizing Evidence Based Practice Define Formulate problem question Re evaluate Gather best Evidence Based Practice evidence Make Evaluate decision Evidence Integrate evidence with family values and expertise www.teachinngei.org p. 1 Define the Problem When a service provider is attempting to understand a new problem, often their questions are broad making it difficult to gather information to inform decisions. Narrowing the problem to certain element gives the best starting point in a search for evidence. Formulate the Question A well constructed question makes the search for evidence easier and more efficient. A good question should contain the specific group or population, the intervention or issue being addressed/ compared and the desired outcome. Gathering the Best Evidence Many sources of evidence come together to inform decisions made about practice. It is important to have the skills and strategies to make timely and effective decisions. Sources of best evidence include • Information sources: publications, databases, web sites, laws and policies • Service provider experience and expertise • Family values, beliefs, priorities and concerns Information Sources: 1. Publications There are a wide range of publications available with information about practice across disciplines in early childhood. Scholarly publications are the most likely to yield accurate information needed to make decisions. These sources include: o Peer-reviewed journals o Research articles o Guidelines and recommended practices o Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis o Books o Reports o Magazines, non- peer reviewed journals 1a. Peer Reviewed Information Information from peer-reviewed or refereed publications is considered high quality because the process to publish requires the scrutiny of experts in the field as well as scientific methods. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Clinical Judgement in the era of Evidence Based Medicine Flores Sepulveda, Luis Jose Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to: Share: to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Nov. 2017 Clinical judgment in the era of Evidence Based Medicine Submitted to the Department of Philosophy of King’s College London, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of philosophy Luis Flores MD. -

Downloads Presented on the Abstract Page

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.27.063578; this version posted April 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A systematic examination of preprint platforms for use in the medical and biomedical sciences setting Jamie J Kirkham1*, Naomi Penfold2, Fiona Murphy3, Isabelle Boutron4, John PA Ioannidis5, Jessica K Polka2, David Moher6,7 1Centre for Biostatistics, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom. 2ASAPbio, San Francisco, CA, USA. 3Murphy Mitchell Consulting Ltd. 4Université de Paris, Centre of Research in Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Inserm, Paris, F-75004 France. 5Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS) and Departments of Medicine, of Epidemiology and Population Health, of Biomedical Data Science, and of Statistics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. 6Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada. 7School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. *Corresponding Author: Professor Jamie Kirkham Centre for Biostatistics Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health The University of Manchester Jean McFarlane Building Oxford Road Manchester, M13 9PL, UK Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)161 275 1135 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.27.063578; this version posted April 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

This Is the Title of My Thesis

A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Interventions (Pharmaceutical and Psychosocial) for Cognitive and Learning Impairments in Children Diagnosed with a Brain Tumour Lisa-Jane Keegan Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Clinical Psychology (D. Clin. Psychol.) The University of Leeds School of Medicine Academic Unit of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences September 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Lisa-Jane Keegan (Optional) The right of Lisa-Jane Keegan to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am sincerely grateful for the help of Professor Stephen Morley and Dr Matthew Morrall, without their support, time and patience this thesis would never have been possible. A big thank you to Miss Rosa Reed-Berendt (Research Assistant), Mr Paul Farrington (Psychologist in Forensic Training), Miss Elizabeth Neilly – Health Faculty Team Librarian, Ms Janet Morton – Education Faculty Team Librarian, Drs Picton, Wilkins and Elliott - Consultant Paediatric Oncologists, Dr Livingston - Consultant Paediatric Neurologist at The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Miss Helen Stocks, Miss Kate Ablett and Dr Stanley, Consultant Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist, Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust, Suzanne Donald (Honorary Research Assistant) and Michael Ferriter- Lead for Research, Forensic Division, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust; who have supported me to achieve my goal. -

Anesthetic Considerations for the Parturient with Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Levi G

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Nursing Capstones Department of Nursing 7-12-2018 Anesthetic Considerations for the Parturient with Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Levi G. La Porte Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones Recommended Citation La Porte, Levi G., "Anesthetic Considerations for the Parturient with Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension" (2018). Nursing Capstones. 187. https://commons.und.edu/nurs-capstones/187 This Independent Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Nursing at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nursing Capstones by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: SAFETY OF SUGAMMADEX AND NEOSTIGMINE 1 The Safety and Efficacy in Reversal of Neuromuscular Blockades with Sugammadex versus Neostigmine by Nicole L. Landen Bachelor of Science in Nursing, University of Minnesota, 2014 An Independent Study Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2019 SAFETY OF SUGAMMADEX AND NEOSTIGMINE 2 PERMISSION Title The Safety and Efficacy in Reversal of Neuromuscular Blockades with Sugammadex versus Neostigmine Department Nursing Degree Master of Science In presenting this independent study in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the College of Nursing and Professional Disciplines of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying or electronic access for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my independent study work or, in her absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the School of Graduate Studies. -

Developing PRISMA-RR, a Reporting Guideline for Rapid Reviews of Primary Studies (Protocol)

Developing PRISMA-RR, a reporting guideline for rapid reviews of primary studies (Protocol) Adrienne Stevens1,2, Chantelle Garritty1,2, Mona Hersi1, David Moher1,3,4 1Ottawa Methods Centre, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Canada; 2TRIBE Graduate Program, University of Split School of Medicine, Croatia; 3Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Canada; 4School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Canada; Funding: The development of PRISMA-RR is supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR FRN-142310). The funder had no role in the development of this protocol and will not have a role in the data collection, analyses, interpretation of the data, and publication of the findings. Funding will be sought to develop the Explanation and Elaboration manuscript. Developing PRISMA-RR, a reporting guideline for rapid reviews of primary studies February 2018 INTRODUCTION Systematic reviews are known to be the best evidence upon which to make healthcare decisions, but can take years to complete (1). Rapid reviews have emerged as accelerated and/or abbreviated versions of systematic reviews with certain concessions made in the systematic review process to accommodate decision-making situations that require an expedited compilation of the evidence (2). Rapid reviews are usually conducted for a specific requestor and are typically understood to take 6 months or less to complete. Rapid reviews may differ from systematic reviews in a number of ways, such as the number of abbreviated methods or shortcuts employed and the breadth or scope of the question(s) posed (2–4). Some rapid reviews involve accelerated data mining processes and targeted screening of studies. -

The Evolution of the Science Citation Index Search Engine to the Web of Science, Scientometric Evaluation and Historiography

The Evolution of the Science Citation Index Search Engine to the Web of Science, Scientometric Evaluation and Historiography Eugene Garfield Chairman Emeritus, Thomson ISI 3501 Market Street, Philadelphia PA 19104 Fax: 215-387-1266 Tel. 215-243-2205 [email protected] www.eugenegarfield.org Presented at the University of Barcelona January 24, 2007 _________________________________ The Science Citation Index was proposed over fifty years ago to facilitate the dissemination and retrieval of scientific literature. Its unique search engine based on citation searching was not widely adopted until it was made available online in 1972. Its by product Journal Citation Reports became available in 1975 including its rankings by impact factor. Impact factors were not widely adopted until about a decade ago when they began to be used as surrogates for expected citation frequencies for recently published papers--a highly controversial application of scientometrics in evaluating scientists and institutions. The inventor of the SCI and its companion Social Sciences Citation Index will review its history and discuss their more recent use in graphically visualizing micro-histories of scholarly topics. Using the patented HistCite software for algorithmic historiographic analysis, the genealogy of the Watson-Crick discovery of the double helix structure of DNA and its relationship to the work of Heidelberger, Avery, and others will be discussed. ____________________________________ It is now over fifty years since the idea of the Science Citation Index (SCI) was first promulgated in Science magazine in 1955.i However, as the older generation of scientists will remember Current Contents is the information service that proved to be the primordial revolutionary “idea” which made the practical realization of the SCI possible.