University Chemistry Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crystallography News British Crystallographic Association

Crystallography News British Crystallographic Association Issue No. 100 March 2007 ISSN 1467-2790 BCA Spring Meeting 2007 - Canterbury p8-17 Patrick Tollin (1938 - 2006) p7 The Z’ > 1 Phenomenon p18-19 History p21-23 Meetings of Interest p32 March 2007 Crystallography News Contents 2 . From the President 3 . Council Members 4 . BCA Letters to the Editor 5 Administrative Office, . Elaine Fulton, From the Editor 6 Northern Networking Events Ltd. 7 1 Tennant Avenue, Puzzle Corner College Milton South, . East Kilbride, Glasgow G74 5NA Scotland, UK Patrick Tollin (1938 - 2006) 8-17 Tel: + 44 1355 244966 Fax: + 44 1355 249959 . e-mail: [email protected] BCA 2007 Spring Meeting 16-17 . CRYSTALLOGRAPHY NEWS is published quarterly (March, June, BCA 2007 Meeting Timetable 18-19 September and December) by the British Crystallographic Association, . and printed by William Anderson and Sons Ltd, Glasgow. Text should The Z’ > 1 Phenomenon 20 preferably be sent electronically as MSword documents (any version - . .doc, .rtf or .txt files) or else on a PC disk. Diagrams and figures are most IUCr Computing Commission 21-23 welcome, but please send them separately from text as .jpg, .gif, .tif, or .bmp files. Items may include technical articles, news about people (e.g. History . 24-27 awards, honours, retirements etc.), reports on past meetings of interest to crystallographers, notices of future meetings, historical reminiscences, Groups .......................................................... 28-31 letters to the editor, book, hardware or software reviews. Please ensure that items for inclusion in the June 2007 issue are sent to the Editor to arrive Meetings . 32 before 25th April 2007. -

Carbon Dioxide Adsorption by Metal Organic Frameworks (Synthesis, Testing and Modeling)

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-8-2013 12:00 AM Carbon Dioxide Adsorption by Metal Organic Frameworks (Synthesis, Testing and Modeling) Rana Sabouni The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Prof. Sohrab Rohani The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Chemical and Biochemical Engineering A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Rana Sabouni 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Chemical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Sabouni, Rana, "Carbon Dioxide Adsorption by Metal Organic Frameworks (Synthesis, Testing and Modeling)" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1472. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1472 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i CARBON DIOXIDE ADSORPTION BY METAL ORGANIC FRAMEWORKS (SYNTHESIS, TESTING AND MODELING) (Thesis format: Integrated Article) by Rana Sabouni Graduate Program in Chemical and Biochemical Engineering A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada Rana Sabouni 2013 ABSTRACT It is essential to capture carbon dioxide from flue gas because it is considered one of the main causes of global warming. Several materials and various methods have been reported for the CO2 capturing including adsorption onto zeolites, porous membranes, and absorption in amine solutions. -

Applying Andragogy to Promote Active Learning in Adult Education In

SHORT PAPER APPLYING ANDRAGOGY TO PROMOTE ACTIVE LEARNING IN ADULT EDUCATION IN RUSSIA Applying Andragogy to Promote Active Learning in Adult Education in Russia https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v6i4.6079 I.V. Pavlova1 and P.A.Sanger2 1 Kazan National Research Technological University, Kazan, Russian Federation 2 Purdue Polytechnic Institute, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA Abstract—In this rapidly changing world of technology and acquire invaluable experience themselves and by observa- economic conditions, it is essential that practicing engineers tion of others in their environment. This experience gives and engineering educators continue to grow in their skills the learner a rich context for applying new knowledge and and knowledge in order to stay competitive and relevant in new techniques. Therefore, as new programs are devel- the industrial and educational work space. This paper de- oped, the student’s professional experience is a valuable scribes the results for a course that combined the best tech- resource and should be incorporated into the curricular niques of andragogy to promote active learning in a curricu- strategy. Active learning using many of the tools from lum of chemistry education, in particular, chemistry labora- andragogy and project based learning could be an attrac- tory education. This experience with two separate corre- tive approach to capitalize on their experience. spondence classes with similar demographics are reported on. Questionnaires and oral open-ended discussions were II. ACTIVE LEARNING APPROACHES USING used to assess the outcome of this effort. Overall the ap- ANDRAGOGY proach received positive reception while pointing out that correspondence students have full time jobs and active Although the early concepts on adult education go back learning in general requires more effort and time. -

Single-Purchase Product Guide Ebooks Connect Your Library Users to the Information They Need Most

Single-purchase product guide eBooks Connect your library users to the information they need most over over over 1,300 25,000 480,000 books chapters pages eBook features Convenient online access • Books can be split by chapter to • MARC records and comprehensive usage read and download statistics, free of charge • Easy to use, powerful • Perpetual ownership search features • Unlimited access and usage • Downloads can be saved in • All titles DOI indexed to chapter level multiple formats Truly scalable Choose a package to suit your needs, or create one from scratch The complete collection Annual collections All 1,300 eBooks in one package Update your collection year by year Pick and Choose Subject collections Your pick of key titles, minimum spend £1,000 Smaller sets, focusing on specific topic areas Try before you buy... ...or start a conversation To access the first chapters of For more details on our eBook our entire eBook collection for packages contact your account free, visit manager or email rsc.li/echapters [email protected] Print books High quality, globally respected chemical science titles that span the breadth of our subject Book sets Collections of print books sorted by subject area or theme – a cost-effective way to get all the titles you need. Choose from 30 sets in a range of subjects, including: • Water • Green • Waste • General chemistry • Catalysis • Metals • Nanoscience • Neuroscience • Drug discovery • Agriculture and toxicology • Polymers • Energy • Computational Prices start from just £165. Browse the full range of book sets at rsc.li/bookset Specialist periodical reports: critical reviews of recent literature Specialist periodical reports (SPRs) are essential Contributing authors analyse, evaluate and for keeping on top of literature and current distil the latest progress in their specialist opinion in particular research fields. -

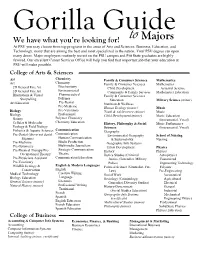

Gorilla Guide for Majors Activity

Gorilla Guide Gorilla Guide We have what you’re looking for! to Majors At PSU you may choose from top programs in the areas of Arts and Sciences, Business, Education, and Technology, many that are among the best and most specialized in the nation. Your PSU degree can open many doors. Major employers routinely recruit on the PSU campus and Pitt State graduates are highly favored. Our excellent Career Services Office will help you find that important job that your education at PSU will make possible. College of Arts & Sciences Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics Art Chemistry Family & Consumer Sciences Mathematics 2D General Fine Art Biochemistry Child Development Actuarial Science 3D General Fine Art Environmental Community & Family Services Mathematics Education Illustrations & Visual Pharmaceutical Family & Consumer Sciences Storytelling Polymer Education Military Science (minor) Art Education Pre-Dental Nutrition & Wellness Pre-Medicine Human Ecology (minor) Music Biology Pre-Veterinary Youth & Adolescence (minor) Music Biology Professional Child Development (minor) Music Education Botany Polymer Chemistry (Instrumental, Vocal) Cellular & Molecular Chemistry Education History, Philosophy & Social Music Performance Ecology & Field Biology Sciences (Instrumental, Vocal) Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences Communication Geography Pre-Dental (this is not dental Communication Environmental Geography School of Nursing hygiene) Human Communication & Sustainability Nursing Pre-Medicine Media Production Geographic Info Systems Pre-Optometry -

Catalog 2011-12

C A T A L O G 1 2011 2012 Professional/Technical Careers University Transfer Adult Education 2 PIERCE COLLEGE CATALOG 2011-12 PIERCE COLLEGE DISTRICT 11 BOARD OF TRUSTEES DONALD G. MEYER ANGIE ROARTy MARC GASPARD JAQUELINE ROSENBLATT AMADEO TIAM Board Chair Vice Chair PIERCE COLLEGE EXECUTIVE TEAM MICHELE L. JOHNSON, Ph.D. Chancellor DENISE R. YOCHUM PATRICK E. SCHMITT, Ph. D. BILL MCMEEKIN President, Pierce College Fort Steilacoom President, Pierce College Puyallup Interim Vice President for Learning and Student Success SUZY AMES Executive Vice President Vice President for Advancement of Extended Learning Programs Executive Director of the Pierce College Foundation JO ANN W. BARIA, Ph. D. Dean of Workforce Education JAN BUCHOLZ Vice President, Human Resources DEBRA GILCHRIST, Ph.D. Dean of Libraries and Institutional Effectiveness CAROL GREEN, Ed.D. Vice President for Learning and Student Success, Fort Steilacoom MICHAEL F. STOCKE Dean of Institutional Technology JOANN WISZMANN Vice President, Administrative Services The Pierce College District does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, disability, or age in its programs and activities. Upon request, this publication will be made available in alternate formats. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Table of Contents Landscapes of Possibilities Dental Hygiene ......................................................52 Sociology ..................................................................77 Chancellor’s Message ..............................................5 -

What Lies Behind Teaching and Learning Green Chemistry to Promote Sustainability Education? a Literature Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review What Lies Behind Teaching and Learning Green Chemistry to Promote Sustainability Education? A Literature Review Meiai Chen 1 , Eila Jeronen 2 and Anming Wang 3,* 1 School of Tourism & Health, Zhejiang A&F University, Hangzhou 311300, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Educational Sciences and Teacher Education, University of Oulu, FI-90014 Oulu, Finland; eila.jeronen@oulu.fi 3 College of Materials, Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 311121, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 September 2020; Accepted: 24 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: In this qualitative study, we aim to identify suitable pedagogical approaches to teaching and learning green chemistry among college students and preservice teachers by examining the teaching methods that have been used to promote green chemistry education (GCE) and how these methods have supported green chemistry learning (GCL). We found 45 articles published in peer-reviewed scientific journals since 2000 that specifically described teaching methods for GCE. The content of the articles was analyzed based on the categories of the teaching methods used and the revised version of Bloom’s taxonomy. Among the selected articles, collaborative and interdisciplinary learning, and problem-based learning were utilized in 38 and 35 articles, respectively. These were the most frequently used teaching methods, alongside a general combination of multiple teaching methods and teacher presentations. Developing collaborative and interdisciplinary learning skills, techniques for increasing environmental awareness, problem-centered learning skills, and systems thinking skills featuring the teaching methods were seen to promote GCL in 44, 40, 34, and 29 articles, respectively. -

BS in Chemistry Education

BS in Chemistry Education (692828) MAP Sheet Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Chemistry and Biochemistry For students entering the degree program during the 2021-2022 curricular year. This major is designed to prepare students to teach in public schools. In order to graduate with this major, students are required to complete Utah State Office of Education licensing requirements. To view these requirements go to http://education.byu.edu/ess/licensing.html or contact Education Advisement Center, 350 MCKB, 801-422-3426. University Core and Graduation Requirements Suggested Sequence of Courses University Core Requirements: FRESHMAN YEAR JUNIOR YEAR Requirements #Classes Hours Classes 1st Semester 5th Semester CHEM 111* (F) 4.0 CHEM 462 (F) or other Req. #4 3.0 Religion Cornerstones First-year Writing or A HTG 100 (FWSpSu) 3.0 IP&T 371 1.0 Teachings and Doctrine of The Book of 1 2.0 REL A 275 MATH 112 (FWSpSu) 4.0 IP&T 373 1.0 Mormon PWS 150** (FW) or other Requirement #5 3.0 SC ED 353 3.0 Religion Cornerstone course 2.0 PHIL 423* or Requirement 5 3.0 Jesus Christ and the Everlasting Gospel 1 2.0 REL A 250 Total Hours 16.0 Religion elective 2.0 Foundations of the Restoration 1 2.0 REL C 225 *With department approval, CHEM 105 may be substituted for CHEM Open Elective 2.5 Total Hours 15.5 The Eternal Family 1 2.0 REL C 200 111. The Individual and Society **PWS 150 fulfills Requirement #5 and G.E. Biological Sciences. If *PHIL 423 fulfills Requirement #5 and G.E. -

EFC) 2020/2021 – CAMPUS of BIZKAIA Coordinator: [email protected]

ENGLISH FRIENDLY COURSES (EFC) 2020/2021 – CAMPUS OF BIZKAIA https://www.ehu.eus/es/web/ztf-fct/home Coordinator: [email protected] In addition to the general offer of courses taught in English, some Centers also offer for incoming students English Friendly Courses (EFC): subjects taught in Spanish, in which the syllabus summary; lecturer tutoring, examinations and/or papers are available in English. FACULTY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (310) SEMESTER CREDITS SCHEDULEi 26113 Química Orgánica I Annual 9 A 26114 Química Orgánica II Annual 9 M/A 26636 Termodinámica y Física Estadística Annual 12 M/A 26645 Algebra Lineal y Geometría I Annual 12 M/A 26750 Cálculo Numérico en Ingeniería Química Annual 9 A 26757 Ingeniería de Procesos y Producto Annual 9 M/A 26117 Química Física I Annual 9 M/A 26123 Química Física II Annual 9 M 27806 Física Annual 12 M/A 26632 Sensores y Actuadores Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26634 Óptica Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26666 Algebra Lineal y Geometría II Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 A 26677 Ampliación de Métodos Numéricos Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26678 Códigos y Criptografía Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26687 Topología Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26700 Química Ambiental Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26703 Química Organometálica Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26706 Determinación de Estructuras Orgánicas Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26818 Ecología Marina Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 6 M/A 26819 Ecología Forestal Sep. 2020- Jan. 2021 4,5 M/A 26847 Diseño de Sistemas Digitales Sep. -

Winter for the Membership of the American Crystallographic Association, P.O

AMERICAN CRYSTALLOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION NEWSLETTER Number 4 Winter 2004 ACA 2005 Transactions Symposium New Horizons in Structure Based Drug Discovery Table of Contents / President's Column Winter 2004 Table of Contents President's Column Presidentʼs Column ........................................................... 1-2 The fall ACA Council Guest Editoral: .................................................................2-3 meeting took place in early 2004 ACA Election Results ................................................ 4 November. At this time, News from Canada / Position Available .............................. 6 Council made a few deci- sions, based upon input ACA Committee Report / Web Watch ................................ 8 from the membership. First ACA 2004 Chicago .............................................9-29, 38-40 and foremost, many will Workshop Reports ...................................................... 9-12 be pleased to know that a Travel Award Winners / Commercial Exhibitors ...... 14-23 satisfactory venue for the McPherson Fankuchen Address ................................38-40 2006 summer meeting was News of Crystallographers ...........................................30-37 found. The meeting will be Awards: Janssen/Aminoff/Perutz ..............................30-33 held at the Sheraton Waikiki Obituaries: Blow/Alexander/McMurdie .................... 33-37 Hotel in Honolulu, July 22-27, 2005. Council is ACA Summer Schools / 2005 Etter Award ..................42-44 particularly appreciative of Database Update: -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Chemistry Education Research and Practice Accepted Manuscript

Chemistry Education Research and Practice Accepted Manuscript This is an Accepted Manuscript, which has been through the Royal Society of Chemistry peer review process and has been accepted for publication. Accepted Manuscripts are published online shortly after acceptance, before technical editing, formatting and proof reading. Using this free service, authors can make their results available to the community, in citable form, before we publish the edited article. We will replace this Accepted Manuscript with the edited and formatted Advance Article as soon as it is available. You can find more information about Accepted Manuscripts in the Information for Authors. Please note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the text and/or graphics, which may alter content. The journal’s standard Terms & Conditions and the Ethical guidelines still apply. In no event shall the Royal Society of Chemistry be held responsible for any errors or omissions in this Accepted Manuscript or any consequences arising from the use of any information it contains. www.rsc.org/cerp Page 1 of 15 Chemistry Education Research and Practice 1 2 Chemistry Education Research and Practice RSCPublishing 3 4 5 ARTICLE 6 7 8 9 Education for sustainable development in chemistry 10 – Challenges, possibilities and pedagogical models in Manuscript 11 Cite this: DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x 12 Finland and elsewhere 13 14 15 Received 00th April 2014, 16 th Accepted 00 April 2014 M.K. Juntunen,a M.K. Akselab, 17 18 DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x 19 This article analyses Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in chemistry by reviewing existing www.rsc.org/ 20 challenges and future possibilities on the levels of the teacher and the student.