February, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cincinnati Reds'

CCIINNCCIINNNNAATTII RREEDDSS PPRREESSSS CCLLIIPPPPIINNGGSS MARCH 1,, 2014 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY: MARCH 1, 2007 – THE FATHER AND SON DUO, MARTY AND THOM BRENNAMAN, CALLED THEIR FIRST REDS GAME AS BROADCAST PARTNERS ON 700 WLW. THE TWO WORKED TOGETHER ONCE BEFORE ON A CUBS-REDS GAME IN THE EARLY 1990S FOR THE BASEBALL NETWORK. THEY BECAME THE FOURTH FATHER SON BROADCAST TEAM IN MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL (JOE AND JOHN BUCK, HARRY, SKIP AND CHIP CARAY AND HARRY AND TODD KALAS). CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Intensity is always Tony Cingrani's specialty Cingrani has one speed, and that's going all out By C. Trent Rosecrans GOODYEAR, ARIZ. — Tony Cingrani gets angry every time he gives up a hit. It doesn’t matter if it’s a spring training exhibition game – like the one he will start Saturday against the Colorado Rockies – or against the St. Louis Cardinals. As the Reds’ second-year starter sees it, it’s his job to not give up any hits and if he gives up a hit, he didn’t do his job. That makes him angry – and like a famous fictional character, you wouldn’t like him when he’s angry. “That’s how I get myself fired up. I need to throw harder, so I try to get super angry and throw it harder,” Cingrani said. “I’m not turning green – I’m trying to scare somebody and see what happens.” Cingrani’s intensity even turned into a meme among Reds fans, with the “Cingrani Face” becoming synonymous with an intense, scary mug. Cingrani said he saw that, and even chuckles quietly about it. -

2019 Topps Series 1 Checklist

BASE VETERANS 1 Ronald Acuña Jr. Atlanta Braves™ Rookie Cup 2 Tyler Anderson Colorado Rockies™ 3 Eduardo Nunez Boston Red Sox® World Series Highlights 4 Dereck Rodriguez San Francisco Giants® Future Stars 5 Chase Anderson Milwaukee Brewers™ 6 Max Scherzer Washington Nationals® League Leaders 7 Gleyber Torres New York Yankees® Rookie Cup 8 Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® 9 Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® 10 Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® 11 Mike Zunino Seattle Mariners™ 12 Crackin' Jokes Major League Baseball® 13 David Price Boston Red Sox® 14 The Yankees® Win! New York Yankees® 15 J.P. Crawford Philadelphia Phillies® 16 Charlie Blackmon Colorado Rockies™ 17 Caleb Joseph Baltimore Orioles® 18 Blake Parker Angels® 19 Jacob deGrom New York Mets® League Leaders 20 Jose Urena Miami Marlins® 21 Jean Segura Seattle Mariners™ 22 Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® 23 J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® League Leaders 24 Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders 25 Chad Green New York Yankees® 26 Angel Stadium™ Angels® 27 Mike Leake Seattle Mariners™ 28 Boston's Boys Boston Red Sox® 29 Eugenio Suarez Cincinnati Reds® 30 Josh Hader Milwaukee Brewers™ 31 Busch Stadium™ St. Louis Cardinals® 32 Carlos Correa Houston Astros® 33 Jacob Nix San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Josh Donaldson Cleveland Indians® 35 Joey Rickard Baltimore Orioles® 36 Paul Blackburn Oakland Athletics™ 37 Marcus Stroman Toronto Blue Jays® 38 Kolby Allard Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 39 Richard Urena Toronto Blue Jays® 40 Jon Lester Chicago Cubs® 41 Corey Seager Los Angeles Dodgers® 42 Edwin Encarnacion Cleveland Indians® 43 Nick Burdi Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 44 Jay Bruce New York Mets® 45 Nick Pivetta Philadelphia Phillies® 46 Jose Abreu Chicago White Sox® 47 Yankee Stadium™ New York Yankees® 48 PNC Park™ Pittsburgh Pirates® 49 Michael Kopech Chicago White Sox® Rookie 50 Mookie Betts Boston Red Sox® 51 Michael Brantley Cleveland Indians® 52 J.T. -

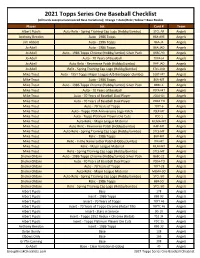

2021 Topps Series One Checklist Baseball

2021 Topps Series One Baseball Checklist (All Cards except unannounced Base Variations); Orange = Auto/Relic; Yellow = Base Rookie Player Set Card # Team Albert Pujols Auto Relic - Spring Training Cap Logo (Hobby/Jumbo) STCL-AP Angels Anthony Rendon Auto - 1986 Topps 86A-ARE Angels Jim Abbott Auto - 1986 Topps 86A-JA Angels Jo Adell Auto - 1986 Topps 86A-JAD Angels Jo Adell Auto - 1986 Topps Chrome (Hobby/Jumbo) Silver Pack 86BC-90 Angels Jo Adell Auto - 70 Years of Baseball 70YA-JA Angels Jo Adell Auto Relic - Reverence Patch (Hobby/Jumbo) RAP-JAD Angels Jo Adell Relic - Spring Training Cap Logo (Hobby/Jumbo) STCL-JAD Angels Mike Trout Auto - 1951 Topps Major League A/S Boxtopper (Jumbo) 51BT-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto - 1986 Topps 86A-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto - 1986 Topps Chrome (Hobby/Jumbo) Silver Pack 86BC-1 Angels Mike Trout Auto - 70 Years of Baseball 70YA-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto - 70 Years of Baseball Dual Player 70DA-GT Angels Mike Trout Auto - 70 Years of Baseball Dual Player 70DA-TO Angels Mike Trout Auto - 70 Years of Topps 70YT-6 Angels Mike Trout Auto - Topps 70th Anniversary Logo Patch 70LP-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto - Topps Platinum Players Die Cuts PDC-1 Angels Mike Trout Auto Relic - Major League Material MLMA-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto Relic - Reverence Patch (Hobby/Jumbo) RAP-MT Angels Mike Trout Auto Relic - Spring Training Cap Logo (Hobby/Jumbo) STCL-MT Angels Mike Trout Relic - 1986 Topps 86R-MT Angels Mike Trout Relic - In the Name Letter Patch (Hobby/Jumbo) ITN-MT Angels Mike Trout Relic - Major League Material -

ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CINCINNATI COLORADO LOS ANGELES Tim Locastro Ronald Acuna, Jr

ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CINCINNATI COLORADO LOS ANGELES Tim Locastro Ronald Acuna, Jr. Ian Happ Shogo Akiyama Raimel Tapia Mookie Betts Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Kris Bryant Nicholas Castellanos Trevor Story Corey Seager Christian Walker Freddie Freeman Anthony Rizzo Joey Votto Charlie Blackmon Justin Turner Kole Calhoun Marcell Ozuna Javier Baez Eugenio Suarez Nolan Arenado Cody Bellinger Eduardo Escobar Travis d’Arnaud Kyle Schwarber Mike Moustakas Daniel Murphy Max Muncy David Peralta Nick Markakis Willson Contreras Jesse Winker Josh Fuentes A.J. Pollock Nick Ahmed Johan Camargo Jason Heyward Nick Senzel Matt Kemp Joc Pederson Daulton Varsho Adam Duvall Victor Caratini Brian Goodwin Ryan McMahon Kike Hernandez Carson Kelly Austin Riley Jason Kipnis Freddie Galvis Kevin Pillar Will Smith Stephen Vogt Ozzie Albies Nico Hoerner Tucker Barnhart Garrett Hampson Austin Barnes Josh Rojas Ender Inciarte David Bote Curt Casali Tony Wolters Chris Taylor Jon Jay Tyler Flowers Cameron Maybin Kyle Farmer Elias Diaz Matt Beaty Josh VanMeter Adeiny Hechavarria Jose Martinez Jose Garcia Drew Butera Edwin Rios Pavin Smith Matt Adams Ildemaro Vargas Aristides Aquino Chris Owings Gavin Lux Andy Young Max Fried Albert Almora Matt Davidson Sam Hilliard Clayton Kershaw Zac Gallen Kyle Wright Yu Darvish Luis Castillo David Dahl Dustin May Luke Weaver Ian Anderson Jon Lester Trevor Bauer German Marquez Julio Urias Madison Bumgarner Robbie Erlin Kyle Hendricks Sonny Gray Kyle Freeland Tony Gonsolin Alex Young Touki Toussaint Alec Mills Tyler Mahle Antonio Senzatela Walker Buehler Taylor Clarke Huascar Ynoa Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Ryan Castellani Blake Treinen Merrill Kelly Shane Greene Adbert Alzolay Wade Miley Jon Gray Kenley Jansen Stefan Crichton Mark Melancon Jeremy Jeffress Raisel Iglesias Chi Chi Gonzalez Dylan Floro Junior Guerra A.J. -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31). -

Cincinnati Reds'

CCIINNCCIINNNNAATTII RREEDDSS PPRREESSSS CCLLIIPPPPIINNGGSS JULY 16, 2014 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY: JULY 16, 1954 – REDS CF GUS BELL LED CINCINNATI TO A 9-4 VICTORY OVER THE PHILLIES BY DRIVING IN SIX RUNS. BELL WENT 3-FOR-5 WITH TWO HOME RUNS, A DOUBLE AND TWO RUNS SCORED. CINCINNATI ENQUIRER All-Star Game 2015 countdown begins Josh Pichler The first thing to understand about next year's All-Star Game is that it's not a game. It's a five-day convention and sports sensation that will overtake Downtown. Concerts, block parties and a parade will complement Major League Baseball's FanFest, Futures Game, Home Run Derby and the 86th All-Star Game. The event is expected to bring well over 100,000 people to the region – including hundreds of journalists – and beam Cincinnati onto television sets and media platforms across the world. For locals whose only frame of reference is the 1988 All-Star Game, next year's festivities will bear little resemblance to the event that hit town when Marge Schott owned the Cincinnati Reds and Pete Rose was her manager. Players that year came to town on Sunday night, missed a skills competition due to weather and played the game Tuesday. Contrast that with the modern, five-day, fan-driven spectacle. Already, MLB has booked 16,165 hotel room nights for next year from July 11-15 for its contingent of executives, corporate sponsors and guests. That's just a fraction of the expected out-of-town guests. Minneapolis anticipated 160,000 visitors for this year's game, the Minneapolis StarTribune reported. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

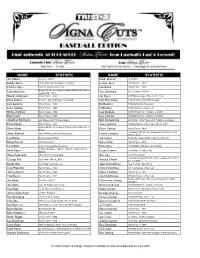

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

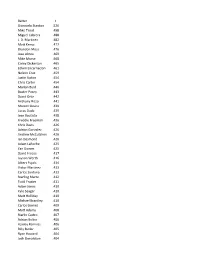

Batter I Giancarlo Stanton .526 Mike Trout .498 Miguel Cabrera .488 J

Batter I Giancarlo Stanton .526 Mike Trout .498 Miguel Cabrera .488 J. D. Martinez .482 Matt Kemp .477 Brandon Moss .476 Jose Abreu .469 Mike Morse .468 Corey Dickerson .465 Edwin Encarnacion .461 Nelson Cruz .459 Justin Upton .454 Chris Carter .454 Marlon Byrd .446 Buster Posey .443 David Ortiz .442 Anthony Rizzo .441 Marcell Ozuna .439 Lucas Duda .439 Jose Bautista .438 Freddie Freeman .436 Khris Davis .426 Adrian Gonzalez .426 Andrew McCutchen .426 Ian Desmond .426 Adam LaRoche .425 Yan Gomes .425 David Freese .417 Jayson Werth .416 Albert Pujols .414 Victor Martinez .413 Carlos Santana .413 Starling Marte .412 Todd Frazier .411 Adam Jones .410 Kyle Seager .410 Matt Holliday .410 Michael Brantley .410 Carlos Gomez .409 Matt Adams .408 Starlin Castro .407 Adrian Beltre .406 Hanley Ramirez .406 Billy Butler .405 Ryan Howard .404 Josh Donaldson .404 Kole Calhoun .400 Russell Martin .400 Anthony Rendon .400 Chase Headley .399 Mark Teixeira .399 Yoenis Cespedes .398 Yasiel Puig .397 Christian Yelich .394 Dexter Fowler .394 Nolan Arenado .393 Joe Mauer .392 Torii Hunter .390 Garrett Jones .389 David Wright .389 Nick Castellanos .388 Jhonny Peralta .388 Justin Morneau .387 Lonnie Chisenhall .386 Seth Smith .386 Jon Jay .385 Luis Valbuena .385 Chris Johnson .385 Evan Longoria .384 Robinson Cano .383 Pablo Sandoval .382 Yadier Molina .382 Jacoby Ellsbury .380 Ryan Braun .379 Daniel Murphy .379 Salvador Perez .378 Alex Gordon .377 Aramis Ramirez .376 Jay Bruce .376 Trevor Plouffe .375 Alex Rios .374 Howie Kendrick .374 Jason Castro .373 Martin Prado .372 Curtis Granderson .372 Jonathan Lucroy .371 Josh Harrison .371 Hunter Pence .371 James Loney .371 Brian Dozier .371 Brett Gardner .371 Asdrubal Cabrera .369 Dioner Navarro .368 Travis d'Arnaud .368 Eric Hosmer .367 Dayan Viciedo .367 Wilin Rosario .367 Neil Walker .366 Melky Cabrera .366 Nick Markakis .365 Scooter Gennett .365 Eduardo Escobar .364 Brandon Phillips .364 Carlos Beltran .364 Miguel Montero .363 Matt Carpenter .361 Denard Span .361 B. -

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release CONTACT: Daniel Kopf – Public & Media Relations Manager [email protected] Phone: 423-267-2208 December 9, 2020 REDS EXTEND AFFILIATE INVITATION TO LOOKOUTS CHATTANOOGA, Tenn. – Today, the Chattanooga Lookouts have received an invitation to remain a minor league affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds. Major League Baseball extended invitations today to 120 teams, marking the new configuration of Minor League Baseball, and the Chattanooga Lookouts are among those receiving an invite. The Lookouts are pleased to have received this invitation and look forward to reviewing the complete terms and conditions of the new license that will be offered by Major League Baseball. “We’ve had professional baseball in Chattanooga since 1885 and we are thrilled to receive an invitation from the Cincinnati Reds that would keep affiliated baseball in the community,” said Lookouts Managing Owner Jason Freier. “We would like to thank the Cincinnati Reds for their continued partnership and their commitment to Chattanooga. We are also grateful to the Chattanooga community and Lookouts’ fans for their outstanding and steadfast support.” While fan support and the Reds desire to stay in Chattanooga were essential, Freier noted that securing the invitation to keep Minor League Baseball in Chattanooga took a true team effort “our cause was helped greatly by the support of leaders such as Mayor Andy Berke, who led a national coalition of Mayors supporting Minor League Baseball, and Congressman Chuck Fleischmann, who strongly championed every initiative to help the Lookouts and Minor League Baseball.” “The Lookouts have one of the most storied histories in the minor leagues. -

November 8, 2011 2012 Topps Museum Collection Baseball Page

November 8, 2011 2012 Topps Museum Collection Baseball Base Cards 1 Jeremy Hellickson Tampa Bay Rays™ 51 Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® 2 Albert Pujols St. Louis Cardinals® 52 Drew Stubbs Cincinnati Reds® 3 Carlos Santana Cleveland Indians® 53 Lou Brock St. Louis Cardinals® 4 Jay Bruce Cincinnati Reds® 54 Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® 5 Don Mattingly New York Yankees® 55 David Price Tampa Bay Rays™ 6 Justin Upton Arizona Diamondbacks® 56 Jered Weaver Angels® 7 Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® 57 Neftali Feliz Texas Rangers® 8 Stan Musial St. Louis Cardinals® 58 Cliff Lee Philadelphia Phillies® 9 Cole Hamels Philadelphia Phillies® 59 Josh Hamilton Texas Rangers® 10 Dan Haren Angels® 60 Carlton Fisk Chicago White Sox® 11 Carl Crawford Boston Red Sox® 61 Ian Kinsler Texas Rangers® 12 Cal Ripken Baltimore Orioles® 62 Roberto Alomar Toronto Blue Jays® 13 Nolan Ryan New York Mets® 63 Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ 14 Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® 64 Roy Halladay Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Derek Jeter New York Yankees® 65 Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® 16 Prince Fielder Milwaukee Brewers™ 66 Andrew McCutchen Pittsburgh Pirates® 17 Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® 67 Victor Martinez Detroit Tigers® 18 Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® 68 Julio Teheran Atlanta Braves™ 19 Ryne Sandberg Chicago Cubs® 69 Felix Hernandez Seattle Mariners™ 20 Matt Holliday St. Louis Cardinals® 70 Ty Cobb Detroit Tigers® 21 Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® 71 Willie Mays San Francisco Giants® 22 Lou Gehrig New York Yankees® 72 Hanley Ramirez Miami Marlins™ 23 Tony Gwynn San -

Cincinnati Reds' Newest Owner Is a Top Official from a New York-Based Global Private Equity and Advisory Firm

CCIINNCCIINNNNAATTII RREEDDSS PPRREESSSS CCLLIIPPPPIINNGGSS OCTOBER 8, 2014 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY: OCTOBER 8, 1880 – CINCINNATI IS KICKED OUT OF THE NATIONAL LEAGUE, DUE IN PART TO ITS REFUSAL TO STOP RENTING OUT THEIR BALLPARK ON SUNDAYS AND TO CEASE SELLING BEER DURING GAMES. CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Fay: Reds should sign Todd Frazier, Devin Mesoraco John Fay Much of the focus this offseason -- actually when you're out of it as early as the Reds were, the offseason starts during the season -- has been on what the Reds will do with the starting pitchers. That's understandable when four of your five starters are a year removed from their walk year, including the ace, Johnny Cueto. The Reds can figure out a way to re-sign Cueto. Really, they realistically could find a way to keep three of the four. But the merits of signing pitchers to long-term deals, especially by a small-market team, is debatable because of the injury risk. What the Reds do with Cueto, Mat Latos, Mike Leake and Alfredo Simon remains to be seen. You can make an argument either way. But the Reds should sign a couple of players to long-term deals this offseason. Neither is a pitcher. I'm talking about Todd Frazier and Devin Mesoraco. Both are arbitration-eligible for the first time. That means they'll go from making a bit over the minimum ($600,000 in Frazier's case; $525,000 in Mesoraco's case) to $3 million or so. If they continue to play like they have, they'll get huge raises in the second and third years of arbitration. -

2018 Topps Heritage High Number Baseball BASE 501 Jordan

2018 Topps Heritage High Number Baseball BASE 501 Jordan Zimmermann Detroit Tigers® 502 Juan Soto Washington Nationals® Rookie 503 Franchy Cordero San Diego Padres™ 504 Ketel Marte Arizona Diamondbacks® 505 Mallex Smith Tampa Bay Rays™ 506 Braxton Lee Miami Marlins® Rookie 507 Jacob Barnes Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie 508 Pedro Alvarez Baltimore Orioles® 509 Alex Blandino Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 510 Pablo Sandoval San Francisco Giants® 511 Scott Kingery Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie 512 Yoshihisa Hirano Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie 513 Jaime Garcia Toronto Blue Jays® 514 Matt Duffy Tampa Bay Rays™ 515 Hunter Strickland San Francisco Giants® 516 Hector Velazquez Boston Red Sox® 517 Jonathan Lucroy Oakland Athletics™ 518 John Axford Toronto Blue Jays® 519 Eduardo Nunez Boston Red Sox® 520 Tony Cingrani Los Angeles Dodgers® 521 Seth Lugo New York Mets® 522 Chris Iannetta Colorado Rockies™ 523 Danny Farquhar Chicago White Sox® 524 Tyler Beede San Francisco Giants® Rookie 525 Daniel Mengden Oakland Athletics™ 526 Steven Souza Jr. Arizona Diamondbacks® 527 Corey Dickerson Pittsburgh Pirates® 528 Matt Szczur San Diego Padres™ 529 Mitch Garver Minnesota Twins® Rookie 530 Trayce Thompson Chicago White Sox® 531 Blake Swihart Boston Red Sox® 532 J.D. Davis Houston Astros® Rookie 533 Trevor Cahill Oakland Athletics™ 534 Niko Goodrum Detroit Tigers® Rookie 535 Pedro Severino Washington Nationals® 536 Asdrubal Cabrera New York Mets® 537 Matt Adams Washington Nationals® 538 Eduardo Escobar Minnesota Twins® 539 Jakob Junis Kansas City Royals® 540 David Bote Chicago Cubs® Rookie 541 Freddy Peralta Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie 542 Marco Gonzales Seattle Mariners™ 543 Ryan Yarbrough Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 544 Fernando Rodney Minnesota Twins® 545 Preston Tucker Atlanta Braves™ 546 Tommy La Stella Chicago Cubs® 547 Clayton Richard San Diego Padres™ 548 Dixon Machado Detroit Tigers® 549 Jose Martinez St.