Memories of Ustad Shaukat Hussain Khan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule for Written Test for the Posts of Lecturers in Various Disciplines

SCHEDULE FOR WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF LECTURERS IN VARIOUS DISCIPLINES Please be informed that written test for the posts of Lecturers in the following departments / disciplines shall be conducted by the University of Sargodha as per schedule mentioned below: Post Applied for: Date & Time Venue 16.09.2018 Department of Business LECTURER IN LAW (Sunday) Administration, (MAIN CAMPUS) University of Sargodha, 09:30 am Sargodha. Roll # Name & Father’s Name 1. Mr. Ahmed Waqas S/o Abdul Sattar 2. Ms. Mahwish Mubeen D/o Mumtaz Khan 3. Malik Sakhi Sultan Awan S/o Malik Abdul Qayum Awan 4. Ms. Sadia Perveen D/o Manzoor Hussain 5. Mr. Hassan Nawaz Maken S/o Muhammad Nawaz Maken 6. Mr. Dilshad Ahmed S/o Abdul Razzaq 7. Mr. Muhammad Kamal Shah S/o Mufariq Shah 8. Mr. Imtiaz Ali S/o Sahib Dino Soomro 9. Mr. Shakeel Ahmad S/o Qazi Rafiq Ahmad 10. Ms. Hina Sahar D/o Muhammad Ashraf 11. Ms. Tahira Yasmeen D/o Sheikh Nazar Hussain 12. Mr. Muhammad Kamran Akbar S/o Mureed Hashim Khan 13. Mr. M. Ahsan Iqbal Hashmi S/o Makhdoom Iqbal Hussain Hashmi 14. Mr. Muhammad Faiq Butt S/o Nazzam Din Butt 15. Mr. Muhammad Saleem S/o Ghulam Yasin 16. Ms. Saira Afzal D/o Muhammad Afzal 17. Ms. Rubia Riaz D/o Riaz Ahmad 18. Mr. Muhammad Sarfraz S/o Ijaz Ahmed 19. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan S/o Farzand Ali Khan 20. Mr. Safdar Hayat S/o Muhammad Hayat 21. Ms. Mehwish Waqas Rana D/o Muhammad Waqas 22. -

Details of Unclaimed Insurance Benefits As at September 30, 2019

DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 1 Iqbal Hussain Shaikh 2 Faisal Aziz 3 Khalid Mahmood 4 Kamal Khan Laghri 5 Haleema Bibi 6 Jamila Ali 7 Manzoor Ahmed Khokar 8 Faisal Cheema 9 Iqbal Hussain Lakho 10 Mohammad Ali 11 Mazher Mohib 12 Zahid Mehmood 13 Gulzar Hussain 14 Naushad 15 Farah Zeba 16 Shah Sikander 17 Bhagyou 18 Seema Jabeen 19 Imran Ilyas Jutt 20 Iqbal Khanani 21 Iqbal Khanani 22 Malik Nasrullah Jan 23 Anwar Mohammad Ali 24 Mohammad Aamir Ahmed 25 Mohammad Khalid Alvi 26 Hafiz Khalid Hussain 27 Muhammad Jandad 28 Nighat Kanwal Pervez 29 Abdul Hameed 30 Ameer Hamza 31 Shoaib Ali 32 Nasir Khan 33 Muhammad Darvesh Lakhan 34 Zameer Ahmed 35 Shabir Hussain Shah 36 Muhammad Israr 37 Shahzada Saeed Ahmed 38 Nabeela Saddiq Satti 39 Mansoorali DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 40 Naeem Abbas 41 Abdul Kareem 42 Noor Ahmed Korejo 43 Muhammad Sadiq 44 Manzoor Begum 45 Isma Parveen 46 Sheikh M Roman Pervaiz 47 Saleem Akhtar 48 Samreen Ahmed 49 Muhammad Arshad Bhatti 50 Mahwish Madad Ali 51 Mahwish Madad Ali 52 Mahwish Madad Ali 53 Khalid Ali 54 Ghulam Murtaza 55 Hero 56 Muhammad Ibrahim 57 Mohammad Sajjad Khan 58 Waseem Ishaq 59 Adeel Ahmed Siddiqui 60 Noor Jahan 61 Ali Raza 62 Sarfaraz Tunio 63 Majed Khan 64 Tanveer Kosar 65 Ilyas Ahmed 66 Mazhar Ali 67 Mahwish Kanwal 68 Abdul Hai 69 Muneer Ahmed Shaikh 70 Shehzad Gulzar 71 Adnan Ahmed 72 Muhammad Arshad 73 Muhammad Shoukat 74 Muhammad Arif 75 Bashir Ahmed Memon 76 Muhammad Bashir 77 Saeed Ahmed 78 Bakhtyar Ahmed DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 79 Nasreen Khurshid 80 Rahim Baig 81 Muhammad Ijaz 82 Sarwar Hussain 83 Muhammad Zafar 84 Saeed Ullah Khan 85 S.Wajid Hussain 86 Ch. -

Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.No Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID

Details of Employees (Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID Women Medical 1 Dr. Afroze Khan Muhammad Chang (NULL) (NULL) Officer Women Medical 2 Dr. Shahnaz Abdullah Memon (NULL) 4130137928800 (NULL) Officer Muhammad Yaqoob Lund Women Medical 3 Dr. Saira Parveen (NULL) 4130379142244 (NULL) Baloch Officer Women Medical 4 Dr. Sharmeen Ashfaque Ashfaque Ahmed (NULL) 4140586538660 (NULL) Officer 5 Sameera Haider Ali Haider Jalbani Counselor (NULL) 4230152125668 214483656 Women Medical 6 Dr. Kanwal Gul Pirbho Mal Tarbani (NULL) 4320303150438 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 7 Dr. Saiqa Parveen Nizamuddin Khoso (NULL) 432068166602- (NULL) Officer Tertiary Care Manager 8 Faiz Ali Mangi Muhammad Achar (NULL) 4330213367251 214483652 /Medical Officer Women Medical 9 Dr. Kaneez Kalsoom Ghulam Hussain Dobal (NULL) 4410190742003 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 10 Dr. Sheeza Khan Muhammad Shahid Khan Pathan (NULL) 4420445717090 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 11 Dr. Rukhsana Khatoon Muhammad Alam Metlo (NULL) 4520492840334 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 12 Dr. Andleeb Liaqat Ali Arain (NULL) 454023016900 (NULL) Officer Badin S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID 1 MUHAMMAD SHAFI ABDULLAH WATER MAN unknown 1350353237435 10334485 2 IQBAL AHMED MEMON ALI MUHMMED MEMON Senior Medical Officer unknown 4110101265785 10337156 3 MENZOOR AHMED ABDUL REHAMN MEMON Medical Officer unknown 4110101388725 10337138 4 ALLAH BUX ABDUL KARIM Dispensor unknown -

The Constitution and Female-Initiated Divorce in Pakistan: Western Liberalism in Islamic Garb

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLG\34-2\HLG207.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-JUN-11 8:12 THE CONSTITUTION AND FEMALE-INITIATED DIVORCE IN PAKISTAN: WESTERN LIBERALISM IN ISLAMIC GARB KARIN CARMIT YEFET* “[N]o nation can ever be worthy of its existence that cannot take its women along with the men.” Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Founder of Pakistan1 The legal status of Muslim women, especially in family relations, has been the subject of considerable international academic and media interest. This Article examines the legal regulation of di- vorce in Pakistan, with particular attention to the impact of the nation’s dual constitutional commitments to gender equality and Islamic law. It identifies the right to marital freedom as a constitu- tional right in Pakistan and demonstrates that in a country in which women’s rights are notoriously and brutally violated, female di- vorce rights stand as a ray of light amidst the “darkness” of the general legal status of Pakistani women. Contrary to the conven- tional wisdom construing Islamic law as opposed to women’s rights, the constitutionalization of Islam in Pakistan has proven to be a potent tool in the service of women’s interests. Ultimately, I hope that this Article may serve as a model for the utilization of both Islamic and constitutional law to benefit women throughout the Muslim world. Introduction .................................................... 554 R I. All-or-Nothing: Classical Islam’s Gendered Divorce Regime ................................................. 557 R A. The Husband’s Right to Untie the Knot ............... 558 R * I wish to express my deep gratitude to Professors Akhil Reed Amar and Reva Siegel for their thoughtful and inspiring comments. -

Information Technology in Libraries. a Pakistani Perspective. ISBN ISBN-969-8133-21-6 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 255P.; Introduction by Aris Khurshid

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 425 749 IR 057 248 AUTHOR Mahmood, Khalid TITLE Information Technology in Libraries. A Pakistani Perspective. ISBN ISBN-969-8133-21-6 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 255p.; Introduction by Aris Khurshid. AVAILABLE FROM Pak Book Corporation, 2825 Wilcrest, Suite 255, Houston, TX 77042; e-mail: [email protected] (Rs. 395). PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Information Analyses (070)-- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cataloging; *Computer Software; Developing Nations; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Information Technology; Integrated Library Systems; Librarians; *Libraries: *Library Automation; *Library DeveloiInent; Library Education; Library Services; Literature Reviews; Online Catalogs; Professional Continuing Education IDENTIFIERS *Library Computer Systems; Library Security; *Pakistan ABSTRACT This book presents an overview of the present status of the use of library automation hardware and software in Pakistan. The following 20 articles are included: (1) "The Status of Library Automation in Pakistan"; (2) "Promoting Information Technology in Pakistan: the Netherlands Library Development Project"; (3) "Library Software in Pakistan"; (4) "The Best Library Software for Developing Countries: More than 30 Plus Points of Micro CDS/ISIS [Computerized Documentation System/Integrated Set of Information Systems]"; (5) "Micro CDS/ISIS: What's New in Version 3.0"; (6) "Use of Micro CDS/ISIS in Pakistan: A Survey"; (7) "Do You Need a Lamp To Enlighten Your Library: An Introduction to Library Automation -

UBL Employee Pension Fund Trust

UBL Employee Pension Fund Trust Employees Retrenched in 1997 on Pension Fund Scheme List of complete retrenched employees in terms of Supreme Court Orders; Column1 EMPNO EMPLOYEE_NAME 1 113148 SYED ZAFAR ALI 2 113290 IQBAL PERVEZ MIRZA 3 113333 MIAN AHSAN HABIB 4 113388 MUHAMMAD LATIF KHAN 5 113397 S M PARWEZ AKHTAR 6 113449 MUHAMMAD QAYYUM MIRZA 7 113689 MUHAMMAD YUNUS 8 113865 SAADAT ALI 9 113883 SHAH BEHRAM QURESHI 10 113908 CH NAZIR AHMED 11 114361 MUHAMMAD AFZAL 12 114662 MOHAMMAD ASLAM 13 114811 JAMIL UR REHMAN 14 114884 MOHAMMAD ASHRAF JANJUA 15 114909 ANWAR HUSSAIN 16 114945 ZAMIR AHMED 17 114963 MUHAMMAD QUDDUS HASAN SIDDIQUI 18 115016 NASIM AHMED 19 115131 MUHAMMAD HANIF 20 115326 ABDUL QADIR AWAN 21 115423 MUHAMMAD ASHFAQUE 22 115654 ANSAR AHMED 23 115779 MUHAMMED SIDDIQUE ABA ALI 24 115788 WASIM AKHTAR GHANI 25 115867 ABOOBAKER 26 115919 MIRZA AFLAQ BEG 27 116211 SALEEM A BANA 28 116239 MUHAMMAD ISMAIL KHAN AFRIDI 29 116372 GHULAM HUSSAIN 30 116789 TURAB ALI A FRAMEWALA 31 116798 GHULAM AKBAR 32 116804 MUHAMMAD AMIN 33 116877 MUHAMMAD AMIN KHAN 34 117009 MUHAMMAD YOUSUF BAKKER 35 117188 MUHAMMAD IQBAL 36 117197 ALEXANDER MATHEWS 37 117452 KAMALUDDIN 38 117513 S SHAH NAWAZ ZIA 39 117586 ABDUL RAZZAQ TAI 40 117896 BADRUDDIN 41 117984 GUL ALAM KHAN Column1 EMPNO EMPLOYEE_NAME 42 118037 NASEER AHMED 43 118426 MANNAN AHMED 44 118648 S ANJUM HUSSAIN NAQVI 45 119010 MUHAMMAD YAQOOB 46 119199 ZAFAR IQBAL BHATTI 47 119223 RAIS AKHTAR 48 119375 QADRI MUHAMMAD SHAFI 49 119481 MUHAMMED IQBAL 50 119746 ABDUL QAYYUM 51 119807 IQBAL DAYALA -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

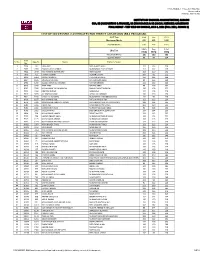

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

Routes 2 Roots Dreams of a Peaceful World Co-Existing with Diverse Cultures, Ruled by Harmony

Routes 2 Roots dreams of a peaceful world co-existing with diverse cultures, ruled by harmony. The world’s largest interactive digital program of teaching performing arts with global reach R-19 LGF, Hauz Khas, New Delhi - 16, Ph: +91 11 41646383 Fax: +91 11 41646384 Studio: Flat No. 5, 1st Floor, Sector - 6 Market, R. K. Puram, New Delhi - 110022, Ph: +91 11 26100114, 26185281 Web: www.routes2roots.com, www.r2rvirsa.in, Email: [email protected] An Initiative of Routes2Roots NGO Routes2Roots twitter.com/Routes2RootsNGO twitter.com/virsar2r virsabyroutes2roots.blogspot.in Board of Advisors & Contributing Maestros of Virsa ROUTES 2 ROOTS Routes 2 Roots is a Delhi based non-profit reputed NGO with a presence all over India. Since its inception in 2004 the NGO is constantly striving to disseminate culture, art and heritage to the common people and the children throughout the world. Ever since its inception in 2004 Routes 2 Roots has dedicated itself to promoting art, culture and heritage throughout the world with the prime objective of spreading the message of peace. We have hosted over 26 international events, 14 exhibitions and 110 concerts throughout the world and all of these programs have been on a non-commercial basis, i.e. no ticketing so that people en masse can come and enjoy a shared experience of each-others’ culture freely. Our organisation is known for quality cultural programs and we have to our credit numerous prestigious international programs such as celebration of 60 years of diplomatic ties between India and China, which was held in 4 cities of China, Celebration of 65 years of Indo-Russian diplomatic ties, which was held in 5 cities of Russia, Festival of India in South Africa covering 4 cities and many more. -

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. the Sound Used for Music Is Technically Known As (A) Anahat Nada (B) Rava (C) Ahat Nada (D) All of the Above

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. The sound used for music is technically known as (a) Anahat nada (b) Rava (c) Ahat nada (d) All of the above 2. Experiment ‘Sarna Chatushtai’ was done to prove (a) Swara (b) Gram (c) Moorchhana (d) Shruti 3. How many Grams are mentioned by Bharat ? (a) Three (b) Two (c) Four (d) One 4. What are Udatt-Anudatt ? (a) Giti (b) Raga (c) Jati (d) Swara 5. Who defined the Raga for the first time ? (a) Bharat (b) Matang (c) Sharangdeva (d) Narad 6. For which ‘Jhumra Tala’ is used ? (a) Khyal (b) Tappa (c) Dhrupad (d) Thumri 7. Which pair of tala has similar number of Beats and Vibhagas ? (a) Jhaptala – Sultala (b) Adachartala – Deepchandi (c) Kaharva – Dadra (d) Teentala – Jattala 8. What layakari is made when one cycle of Jhaptala is played in to one cycle of Kaharva tala ? (a) Aad (b) Kuaad (c) Biaad (d) Tigun 9. How many leger lines are there in Staff notation ? (a) Five (b) Three (c) Seven (d) Six 10. How many beats are there in Dhruv Tala of Tisra Jati in Carnatak Tala System ? (a) Thirteen (b) Ten (c) Nine (d) Eleven 11. From which matra (beat) Maseetkhani Gat starts ? (a) Seventh (b) Ninth (c) Thirteenth (d) Twelfth Series-A 2 SPU-12 1. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 2. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 3. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 4. - ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 5. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 6. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 7. ? (a) – (b) – (c) – (d) – 8. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 9. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 10. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2020 (PAGE 4) PERSONALITY MOVIE-REVIEW Tributes to Tabla maestro SHIKARA Ravi Rohmetra Ustad Allah Rakha A potboiler that uses KP Exodus only as a backdrop Khan, the country's Leading Tabla Exponet Ravinder Kaul refuse to show any perceptible sign of was born on 29th April aging. The only characters in the film who 1919 at Phagwal It has been 30 years since 4 lakh Kash- look quite genuine and authentic are the Village of Dist. miri Pandits were forced to leave their 4000 Kashmiri Pandit refugees, who SAMBA, Jammu in a centuries old place of habitat, in the wake form the crowds in the refugee camps in of armed Islamic insurgency, to live a mis- Punjabi Gharana. His Jammu. erable life in torn tents and ramshackle The background music has been com- mother tongue was rooms, away from their homes in the pris- posed by AR Rahman and Qutub-e-Kirpa, Dogri. He became fas- tine beautiful valley of Kashmir. The while the songs have been composed by cinated with the sound tragedy of the victims of the biggest Abhay Rustam Sopori and Sandesh and rhythm of the migration in India since independence Shandilya. The Chhakari song 'Shukrana tabla at the age of 12 got further aggravated when no main- Gul Khiley', composed by Abhay Rustam stream political party and no human years. He used to be Sopori, written by Bashir Arif and sung by rights or social organization took any fascinated by the Munir Meer, and the strains of Santoor in notice of their sufferings.