Istanbul Technical University Graduate School of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Lietuvos Muzikologija 19.Indd

Lietuvos muzikologija, t. 19, 2018 Viktorija KOLAROVSKA-GMIRJA The Macedonian National School of Composition: The Specifics of Foundation and Development Makedonijos nacionalinė kompozicijos mokykla, jos įsteigimo ir plėtotės aspektai Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Faculty of Music, Pitu Guli 1, 1000 Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Email [email protected] Abstract The article discusses the distinctive features of the Macedonian national school of composition. The school was founded in the cultural con- text of the 20th century and covered the following components: a) professional component: a unifying idea of adopting the European model of composing activity; b) stylistic / aesthetic component: the simultaneous existence of different stylistic tendencies, positioning numerous composers from different generations as promoters of the national idea; c) educational component: non-institutional and institutional forms of education, the influence of the cultural and educational centres from other areas on the expansion of the stylistic and aesthetic directions and modernizing the composing education. Keywords: Macedonian national school of composition, professional component, stylistic / aesthetic component, educational component, 20th century. Anotacija Straipsnyje aptariami būdingi Makedonijos nacionalinės kompozicijos mokyklos bruožai. Ši mokykla buvo įsteigta XX a. kultūriniame kontekste ir apėmė šiuos aspektus: a) profesinis aspektas: bendrinė idėja priimti europietiškąjį kompozicijos modelį; b) stilistinis / estetinis -

The Great Choral Treasure Hunt Vi

THE GREAT CHORAL TREASURE HUNT VI Margaret Jenks, Randy Swiggum, & Rebecca Renee Winnie Friday, October 31, 2008 • 8:00-9:15 AM • Lecture Hall, Monona Terrace Music packets courtesy of J.W. Pepper Music YOUNG VOICES Derek Holman: Rattlesnake Skipping Song Poem by Dennis Lee 5. From Creatures Great and Small From Alligator Pie Boosey & Hawkes OCTB6790 [Pepper #3052933] SSA and piano Vincent Persichetti: dominic has a doll e.e. cummings text From Four Cummings Choruses Op. 98 2-part mixed, women’s, or men’s voices Elkam-Vogel/Theodore Presser 362-01222 [Pepper #698498] Another recommendation from this group of choruses: maggie and milly and molly and may David Ott: Garden of Secret Thoughts From: Garden of Secret Thoughts Plymouth HL-534 [Pepper #5564810] 2 part and piano Other Recommendations: Geralad Finzi: Dead in the Cold (From Ten Children’s Songs Op. 1) Poems by Christina Rossetti Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #1542752] 2 part and piano Elam Sprenkle: O Captain, My Captain! (From A Midge of Gold) Walt Whitman Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #1801455] SA and piano Carolyn Jennings: Lobster Quadrille (From Join the Dance) Lewis Carroll Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #1761790] SA and piano Victoria Ebel-Sabo: Blustery Day (The Challenge) Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #3050515} unison and piano Paul Carey: Seal Lullaby Rudyard Kipling Roger Dean [Pepper #10028100} SA and piano Zoltán Kodály: Ladybird (Katalinka) Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #158766] SSA a cappella This and many other Kodály works found in Choral works for Children’s and Female voices, Editio Musica Budapest Z.6724 MEN’S VOICES Ludwig van Beethoven: Wir haben ihn gesehen Christus am Ölberge (Franz Xavier Huber) Alliance AMP 0668 [Pepper # 10020264] Edited by Alexa Doebele TTB piano (optional orchestral score) WOMEN’S VOICES Princess Lil’uokalani, Arr. -

Prepared Objects, Compositions That Use Them, and the Resulting Sound Dr

Prepared objects, compositions that use them, and the resulting sound Dr. Stacey Lee Russell Under/On Aluminum foil 1. Beste, Incontro Concertante Buzzing, rattling 2. Brockshus, “I” from Greytudes the keys Cigarette 1. Zwaanenburg, Solo for Prepared Flute Buzzing, rattling paper 2. Szigeti, That’s for You for 3 flutes 3. Matuz, “Studium 6” from 6 Studii per flauto solo 4. Gyӧngyӧssy, “VII” from Pearls Cork 1. Ittzés, “A Most International Flute Festival” Cork is used to wedge specific ring keys into closed positions. Mimics Bansuri, Shakuhachi, Dizi, Ney, Kaval, Didgeridoo, Tilinka, etc. Plastic 1. Bossero, Silentium Nostrum “Inside a plastic bag like a corpse,” Crease sound, mimic “continuous sea marine crackling sensation.” Plastic bag 1. Sasaki, Danpen Rensa II Buzzing, rattling Rice paper 1. Kim, Tchong Buzzing, rattling Thimbles 1. Kubisch, “It’s so touchy” from Emergency Scratching, metallic sounds Solos Inside Beads 1. Brockshus, “I” from Greytudes Overtone series, intonation, beating the tube Buzzers 1. Brockshus, “III” from Greytudes Distortion of sound Cork 1. Matuz, “Studium 1” from 6 Studii per flauto Overtone series, note sound solo octave lower than written 2. Eӧtvӧs, Windsequenzen 3. Zwaanenburg, Solo for Prepared Flute 4. Matuz, “Studium 5” from 6 Studii per flauto solo 5. Fonville, Music for Sarah 6. Gyӧngyӧssy, “III” from Pearls 7. Gyӧngyӧssy, “VI” from Pearls Darts 1. Brockshus, “II” from Greytudes Beating, interference tones Erasers & 1. Brockshus, “I” from Greytudes Overtone series, intonation, Earplugs beating Plastic squeaky 1. Kubisch, “Variation on a classical theme” Strident, acute sound toy sausage from Emergency Solos Siren 1. Bossero, Silentium Nostrum Marine signaling, turbine spins/whistles Talkbox 1.Krüeger, Komm her, Sternschnuppe Talkbox tube is hooked up to the footjoint, fed by pre- recorded tape or live synthesizer sounds © Copyright by Stacey Lee Russell, 2019 www.staceyleerussell.com [email protected] x.stacey.russell Towel 1. -

10. Turkey Lurkey

September- week 4: 3. Teach song #11 “Shake the Papaya” by rote. When the students can sing the entire song, use the song as the Musical Concepts: theme of a rondo. Choose or create rhythm patterns to perform as q qr h w variations between the singing of the theme. (You could choose create rondo three rhythm flashcards.) The final form will be: New Songs: Concept: A - sing 10. Turkey Lurkey CD1: 11 smd B - perform first rhythm pattern as many times as needed * show high/middle/low, derive solfa , teacher notates (8 slow beats or 16 fast ones) 11. Shake the Papaya CD1: 12-37 Calypso A - sing * create rondo using unpitched rhythm instruments or C - perform second rhythm pattern boomwhackers smd A - sing D - perform third rhythm pattern Review Songs: Concept: A - sing 8. Whoopee Cushion CD1: 8-9-35 d m s d’, round 9. Rocky Mountain CD1: 10-36 drm sl, AB form You can perform the rhythm patterns on unpitched percussion instruments or on Boomwhackers® (colored percussion tubes). General Classroom Music Lesson: 4. Assess individuals as they sing with the class. Have the children stand up in class list order. Play the song on the CD and have q qr Erase: Use first half of “Rocky Mountain.” the entire class sing. Listen to each child sing alone for a few The rhythm is written as follows. seconds and grade on your class list as you go. For the September assessment use #9 “Rocky Mountain.” qr qr | qr qr | qr qr | h | qr qr | qr qr | qr qr | h || Listening Resource Kit Level 3: Rhythm Erase: Put all eight measures on the board. -

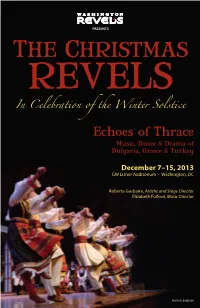

Read This Year's Christmas Revels Program Notes

PRESENTS THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey December 7–15, 2013 GW Lisner Auditorium • Washington, DC Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director PHOTO BY ROGER IDE THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey The Washington Featuring Revels Company Karpouzi Trio Koleda Chorus Lyuti Chushki Koros Teens Spyros Koliavasilis Survakari Children Tanya Dosseva & Lyuben Dossev Thracian Bells Tzvety Dosseva Weiner Grum Drums Bryndyn Weiner Kukeri Mummers and Christmas Kamila Morgan Duncan, as The Poet With And Folk-Dance Ensembles The Balkan Brass Byzantio (Greek) and Zharava (Bulgarian) Emerson Hawley, tuba Radouane Halihal, percussion Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director Gregory C. Magee, Production Manager Dedication On September 1, 2013, Washington Revels lost our beloved Reveler and friend, Kathleen Marie McGhee—known to everyone in Revels as Kate—to metastatic breast cancer. Office manager/costume designer/costume shop manager/desktop publisher: as just this partial list of her roles with Revels suggests, Kate was a woman of many talents. The most visibly evident to the Revels community were her tremendous costume skills: in addition to serving as Associate Costume Designer for nine Christmas Revels productions (including this one), Kate was the sole costume designer for four of our five performing ensembles, including nineteenth- century sailors and canal folk, enslaved and free African Americans during Civil War times, merchants, society ladies, and even Abraham Lincoln. Kate’s greatest talent not on regular display at Revels related to music. -

BUSINESS MASTER PLAN for Development and Construction of a Ski Cente R in the Galičica National Park

BUSINESS MASTER PLAN FOR Development and Construction of a Ski Cente r in the Galičica National Park AD MEPSO d.d. Orce Nikolov b.b. 1000 SKOPJE MASTER PLAN SKI CENTER GALIČICA INTRODUCTION DISCLAIMER Our study and report are based on assumptions and estimates that are subject to uncertainty and variation. In addition, we have made assumptions as to the future behaviour of consumers and the general economy, which are uncertain. This Report is for your internal purposes and for submission to strategic partners and potential creditors of the project. Any use of the Report must include the entire content of such report in the form delivered to you. No portion or excerpts thereof may be otherwise quoted or referred to in any offering statement, prospectus, loan agreement, or other document unless expressly approved in writing by Horwath HTL. Reproducing or copying of this Report may not be done without our prior consent. MASTER PLAN SKI CENTER GALIČICA © COPYRIGHT 2014 by HORWATH HTL All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of Horwath HTL or a license permitting restricted copying. This publication may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without prior consent of Horwath HTL. MASTER PLAN SKI CENTER GALIČICA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 ASSIGNMENT -

Anarchy in Macedonia: Life Under the Ottomans, 1878-1912

Anarchy in Macedonia Life under the Ottomans, 1878-1912 Victor Sinadinoski 1 Copyright © 2016 by Victor Sinadinoski All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1537451886 2 “Macedonia is a field of illusions where nothing is entirely real.” Maurice Gandolphe, 1904 3 (This page intentionally left blank) 4 For my mom, whose love for Macedonia is pure and simple; and for my dad, whose dedication to the Macedonian Cause is infinite. 5 (This page intentionally left blank) 6 Introduction The Ottoman (Turkish)1 Empire reigned over Macedonia from the late 14th century until the final months of 1912. The entire history of Ottoman rule was unfavorable to the Macedonians: their conquerors were ruthless and oppressive. But the period of the Macedonian national resurgence, assuming a recognizable and meaningful form beginning in the 1870s, was extraordinarily burdensome and grueling. These last four decades of Turkish rule in Macedonia can likely be categorized as the bloodiest and most chaotic years of Macedonia’s existence. Unfortunately for the Macedonians, even after the Turks were evicted as their landlords and executioners, the ideals of liberty, justice, dignity and equality remained distant and inaccessible. The Berlin Congress of July 1878 reversed the short-lived Treaty of San Stefano’s decision to attach Macedonia to Bulgaria, a decision inked only a few months prior. The European Powers factored heavily in shaping the outcomes of these treaties. -

PDF Download Solfege, Ear Training, Rhythm, Dictation

SOLFEGE, EAR TRAINING, RHYTHM, DICTATION, AND MUSIC THEORY : A COMPREHENSIVE COURSE Author: Marta Arkossy Ghezzo Number of Pages: 432 pages Published Date: 05 Jul 2005 Publisher: The University of Alabama Press Publication Country: Alabama, United States Language: English ISBN: 9780817351472 DOWNLOAD: SOLFEGE, EAR TRAINING, RHYTHM, DICTATION, AND MUSIC THEORY : A COMPREHENSIVE COURSE Solfege, Ear Training, Rhythm, Dictation, and Music Theory : A Comprehensive Course PDF Book US Army and Marine Corps MRAPs: Mine Resistant Ambush Protected VehiclesVital information on one of the most popular and affordable ranges of performance cars BMW's 3-Series is arguably the most widely admired and sought after range of high-performance saloons on the market, and the first two generations of them - the subject of this reissued volume in MRP's Collector's Guide series - are now available at such attractive prices that the market for them has grown wider than ever. This fascination helped create a whole new world of entertainment, inspiring novels, plays and films, puppet shows, paintings and true-crime journalism - as well as an army of fictional detectives who still enthrall us today. Forgotten Books uses state-of-the-art technology to digitally reconstruct the work, preserving the original format whilst repairing imperfections present in the aged copy. The book is divided into 17 progressive chapters. Perhaps most exciting is that in 2016 the American Museum of Natural History opened a new exhibition featuring the astonishing, newly discovered 122-foot-long titanosaur, yet to be named. jpg" alt"Democracy - The God That Failed" meta itemprop"isbn" content"9780765808684" meta itemprop"name" content"Democracy - The God That Failed" meta itemprop"contributor" content"Hans-Hermann Hoppe" a href"Democracy---The-God-That- Failed-Hans-Hermann-Hoppe9780765808684?refpd_detail_2_sims_cat_bs_1" Democracy - The God That Faileda a href"authorHans-Hermann-Hoppe" itemprop"author"Hans-Hermann Hoppea 31 Oct 2001p US54. -

Timeline / 1810 to 1930

Timeline / 1810 to 1930 Date Country Theme 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts Buildings present innovation in their architecture, decoration and positioning. Palaces, patrician houses and mosques incorporate elements of Baroque style; new European techniques and decorative touches that recall Italian arts are evident at the same time as the increased use of foreign labour. 1810 - 1880 Tunisia Fine And Applied Arts A new lifestyle develops in the luxurious mansions inside the medina and also in the large properties of the surrounding area. Mirrors and consoles, chandeliers from Venice etc., are set alongside Spanish-North African furniture. All manner of interior items, as well as women’s clothing and jewellery, experience the same mutations. 1810 - 1830 Tunisia Economy And Trade Situated at the confluence of the seas of the Mediterranean, Tunis is seen as a great commercial city that many of her neighbours fear. Food and luxury goods are in abundance and considerable fortunes are created through international trade and the trade-race at sea. 1810 - 1845 Tunisia Migrations Taking advantage of treaties known as Capitulations an increasing number of Europeans arrive to seek their fortune in the commerce and industry of the regency, in particular the Leghorn Jews, Italians and Maltese. 1810 - 1850 Tunisia Migrations Important increase in the arrival of black slaves. The slave market is supplied by seasonal caravans and the Fezzan from Ghadames and the sub-Saharan region in general. 1810 - 1930 Tunisia Migrations The end of the race in the Mediterranean. For over 200 years the Regency of Tunis saw many free or enslaved Christians arrive from all over the Mediterranean Basin. -

Eü Devlet Türk Musikisi Konservatuvari Dergisi

I ISSN: 2146-7765 EÜ DEVLET TÜRK MUSİKİSİ KONSERVATUVARI DERGİSİ Sayı: 5 Yıl: 2014 Yayın Sahibi Prof. Dr. M. Öcal ÖZBİLGİN (Ege Üniversitesi Devlet Türk Musikisi Konservatuarı adına) Editör Yrd. Doç. Dr. Füsun AŞKAR Dergi Yayın Kurulu Prof. Dr. M. Öcal ÖZBİLGİN Doç. Dr. Ö. Barbaros ÜNLÜ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Maruf ALASKAN Yrd. Doç. Dr. Füsun AŞKAR Yrd. Doç. Dr. İlhan ERSOY Yrd. Doç. Dr. S. Bahadır TUTU Öğr.Gör. Atabey AYDIN Kapak Fotoğrafları Öğr. Gör. Abdurrahim KARADEMİR ve Ferruh ÖZDİNÇER arşivi’nden Basım Yeri Ege Üniversitesi Basımevi Bornova-İzmir T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Sertifika No: 18679 Basım Tarihi 26.12.2014 Baskı Adedi: 150 Yönetim Yeri Ege Üniversitesi Devlet Türk Musikisi Konservatuarı [email protected] 0 232 388 10 24 Ege Üniversitesi Devlet Türk Musikisi Konservatuarı tarafından yılda iki sayı olarak yayımlanan ulusal hakemli bir dergidir. EGE ÜNİVERSİTESİ DEVLET TÜRK MUSİKİSİ KONSERVATUVARI DERGİSİ HAKEM KURULLARI Prof. Dr. Gürbüz AKTAŞ E.Ü. DTMK Prof. Ş. Şehvar BEŞİROĞLU İTÜ TMDK Prof. Dr. Mustafa Hilmi BULUT C.Ü. GSF Prof. Dr. Hakan CEVHER E.Ü. DTMK Prof. Dr. Ayhan EROL D.E.Ü. GSF Prof. Songül KARAHASANOĞLU İTÜ TMDK Prof. Serpil MÜRTEZAOĞLU İTÜ TMDK Prof. Nihal ÖTKEN İTÜ TMDK Prof. Dr. M. Öcal ÖZBİLGİN E.Ü. DTMK Prof. Berrak TARANÇ E.Ü. DTMK Doç. Dr. F. Reyhan ALTINAY E.Ü. DTMK Doç. Dr. Türker EROĞLU G.Ü. EĞİT. FAK. Doç. Dr. Kürşad GÜLBEYAZ Dicle Ü. Doç. Dr. Belma KURTİŞOĞLU İTÜ TMDK Doç. Bülent KURTİŞOĞLU İTÜ TMDK Doç. Dr. Muzaffer SÜMBÜL Ç.Ü. Eğ. Fak. Doç. Dr. Ö. Barbaros ÜNLÜ E.Ü. -

Doing Business in South East Europe 2008 and Other Subnational and Regional Studies Can Be Downloaded At

© 2008 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, D.C. 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 5 09 08 07 06 A copublication of the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation. This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The World Bank Group encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202- 522-2422; e-mail: [email protected]. Copies of Doing Business 2008, Doing Business 2007: How to Reform, Doing Business in 2006: Creating Jobs, Doing Business in 2005: Removing Obstacles to Growth, and Doing Business in 2004: Understanding Regulations may be obtained at www.doingbusiness.org.