Waiau Catchment Values: 2 What Do We Currently Know?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIORDLAND NATIONAL PARK 287 ( P311 ) © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely ©

© Lonely Planet Publications 287 Fiordland National Park Fiordland National Park, the largest slice of the Te Wahipounamu-Southwest New Zealand World Heritage Area, is one of New Zealand’s finest outdoor treasures. At 12,523 sq km, Fiordland is the country’s largest park, and one of the largest in the world. It stretches from Martins Bay in the north to Te Waewae Bay in the south, and is bordered by the Tasman Sea on one side and a series of deep lakes on the other. In between are rugged ranges with sharp granite peaks and narrow valleys, 14 of New Zealand’s most beautiful fiords, and the country’s best collection of waterfalls. The rugged terrain, rainforest-like bush and abundant water have kept progress and people out of much of the park. Fiordland’s fringes are easily visited, but most of the park is impenetrable to all but the hardiest trampers, making it a true wilderness in every sense. The most intimate way to experience Fiordland is on foot. There are more than 500km of tracks, and more than 60 huts scattered along them. The most famous track in New Zealand is the Milford Track. Often labelled the ‘finest walk in the world’, the Milford is almost a pilgrimage to many Kiwis. Right from the beginning the Milford has been a highly regulated and commercial venture, and this has deterred some trampers. However, despite the high costs and the abundance of buildings on the manicured track, it’s still a wonderfully scenic tramp. There are many other tracks in Fiordland. -

Agenda of Ohai Community Development Area Subcommittee

. . Contents 1 Apologies 2 Leave of absence 3 Conflict of Inter est 4 Public F orum 5 Extraordi nar y/Urgent Items 6 Confirmati on of Minutes Minutes of Ohai Communi ty D evelopment Ar ea Subcommittee 29/05/2018 . 7.1 Ohai H all update ☐ ☐ ☒ 1 The purpose of this report is to provide information about recent works undertaken at the Ohai Hall and to provide an update on the delays for consultation around retention of the Ohai Hall or Bowling Club building. 2 In 2005, the current Cleveland coal burner had a major recondition/overhaul carried out by C H Faul of Invercargill. The intention was that this would give another 15-20 years of life to the burner. 3 In 2015, it was suggested that there was an electrical fault and the burner was taken out of service with the wire being cut between the wall and the thermostat in the main hall and the burner unit. 4 The previous CDA had identified a project to upgrade the windows, paint the interior, install a zip and replace the LED lights. This was costed at approximately $40,000. 5 Subsequent to that decision being made the former Ohai Bowling Club building was gifted back to the community of Ohai and a decision was made to consult with the wider community about the comparative cost of upgrading and maintaining the Bowling Club and the Hall with a view to only keeping one building for use by the community. 6 In February 2018, at the first informal meeting of the new Ohai Community Development Area Subcommittee, the hall heating was identified as being a priority project for the Subcommittee and staff were requested to investigate alternative heating options. -

Full Article

NOTORNIS QUARTERLY JOURNAL of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand Volume Sixteen, Number Two, lune, 1969 NOTICE TO CONTRIBUTORS Contributions should be type-written, double- or treble-spaced, with a wide margin, on one side of the paper only. They should be addressed to the Editor, and are accepted o?, condition that sole publication is being offered in the first instance to Notornis." They should be concise, avoid repetition of facts already published, and should take full account of previous literature on the subject matter. The use of an appendix is recommended in certain cases where details and tables are preferably transferred out of the text. Long contributions should be provided with a brief summary at the start. Reprints: Twenty-five off-prints will be supplied free to authors, other than of Short Notes. When additional copies are required, these will be produced as reprints, and the whole number will be charged to the author by the printers. Arrangements for such reprints must be made directly between the author and the printers, Te Rau Press Ltd., P.O. Box 195, Gisborne, prior to publication. Tables: Lengthy and/or intricate tables will usually be reproduced photographically, so that every care should be taken that copy is correct in the first instance. The necessity to produce a second photographic plate could delay publication, and the author may be called upon to meet the additional cost. nlastrutions: Diagrams, etc., should be in Indian ink, preferably on tracing cloth, and the lines and lettering must be sufficiently bold to allow of reduction. Photographs must be suitable in shape to allow of reduction to 7" x 4", or 4" x 3f". -

![Detailed Itinerary [ID: 1136]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9604/detailed-itinerary-id-1136-239604.webp)

Detailed Itinerary [ID: 1136]

Daniel Collins - Fine Travel 64 9 363 2754 www.finetravel.co.nz Land of the Rings A tour appealing to those Frodo and Gandalf fans, with visits to official sites used in the filming of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Starts in: Auckland Finishes in: Queenstown Length: 9days / 8nights Accommodation: Hotel 3 star Can be customised: Yes This itinerary can be customised to suit you perfectly. We can add more days, remove days, change accommodations, mix it up, add activities to suit your interests or simply design and create something from scratch. Call us today to get your custom New Zealand itinerary underway. Inclusions: Includes: All coach transport Includes: All pick ups/drop offs at destinations Includes: Comprehensive tour pack (detailed Includes: 24/7 support while touring in New itinerary, driving, instructions, map/guidebooks, Zealand brochures) Included activity: Auckland to Rotorua including Included activity: Private transfer Christchurch Waitomo and Hobbiton with GreatSights Airport to your accommodation Included activity: Air New Zealand flight Rotorua Included activity: Rotorua Accommodation to to Christchurch Rotorua Airport - Private Transfer Included activity: Rotorua Duck Tours City & Included activity: Lord of the Rings Edoras Tour Lakes Tour Included activity: Christchurch to Queenstown Included activity: One Day in Middle Earth Full via Mount Cook with GreatSights Day Tour Included activity: Safari of the Scenes Wakatipu Included activity: Queenstown to Te Anau with Basin Tour GreatSights Included activity: Pure Wilderness Jet Boat Included activity: Milford Sound Nature Cruise : Meals included: 1 lunch, 1 dinner For a detailed copy of this itinerary go to http://finetravel.nzwt.co.nz/tour.php?tour_id=1136 or call us on 64 9 363 2754 Day 1 Auckland to Rotorua including Waitomo and Hobbiton Experience with GreatSights Take a journey into the heart of the Central North Island, taking in the Waitomo Caves and Hobbiton Movie Set on a full-day sightseeing tour. -

To: Southland District Council P O Box Invercargill [email protected]

To: Southland District Council P O Box Invercargill [email protected] From: Rosemary Penwarden C/- Counter Mail Blueskin Store 12 Orokonui Road Waitati Otago 03 4822831 [email protected] 25 February 2013 To Whom it May Concern Submission re Proposed Southland District Plan I do wish to be heard in respect of this submission. Introduction I grew up in rural New Zealand (North Island West Coast) and am a long-time resident of Otago, just up the road from Southland. In the past two years I have visited Southland many times, made new friends, seen much of the country and learned in detail about the proposed lignite developments in the Mataura valley. First and foremost I am a concerned citizen of this beautiful home of ours, planet Earth. I am a mother and grandmother, and carry my parental responsibility seriously. We do not have the right to pass on to our children a world in a state of climate chaos, economic and environmental disaster. For the world‟s climate to remain liveable, we must rapidly reduce the current level of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere. The major source of such emissions is the burning of fossil fuels, and of these, coal is the most plentiful. Scientists have made it clear that coal must be phased out to give us any hope of avoiding runaway climate change. Lignite, as the dirtiest form of coal, must stay in the ground. Burning coal also contributes to ocean acidification. Ocean acidification is not an effect of climate change. It is related to a different receiving environment (seawater) and a different physical process (alteration of the chemical composition of the ocean rather than altering the heat trapping capacity of the atmosphere). -

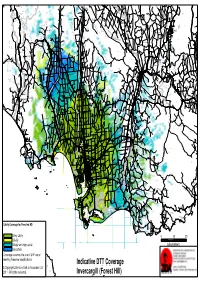

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River

th IPENZ Engineering Heritage Register Report Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River Written by: Karen Astwood Date: 3 September 2012 Clifden Suspension Bridge, newly completed, circa February 1899. Collection of Southland Museum and Art Gallery 1 Contents A. General information ........................................................................................................... 3 B. Description ......................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Historical narrative .................................................................................................................... 6 Social narrative ...................................................................................................................... 11 Physical narrative ................................................................................................................... 12 C. Assessment of significance ............................................................................................. 16 D. Supporting information ...................................................................................................... 17 List of supporting documents ................................................................................................... 17 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

1274 the NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No

1274 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. [No. 38 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 267348 Robertson, Alexander Fraser, railway employee, Tahakopa, 376237 Shanks, John (jun.), farm-manager, Warepa, South Otago. South Otago. 060929 Shanks, Stuart, farm hand, Waikana, Ferndale Rural 281491 Robertson, Alexander William, shepherd, "Warwick Delivery, Gore. Downs," Otapiri Rural Delivery, Winton. 397282 Sharp, Charles, farmer, Tuapeka Mouth. 257886 Robertson, Alfred Roy, labourer, 152 Spay St., Invercargill. 426037 Shaw, Ivan Holden, paper-mill employee, Oakland St., 203202 Robertson, Douglas Belgium, labourer, Roxburgh. Mataura. 262523 Robertson, Eric James, farmer, Heddon Bush Rural Deli very, 282484 Shaw, John, N.Z.R. employee, care of New Zealand Railways, Winton. Milton, South Otago. 151974 Robertson, Francis William, Ellis Rd., care of Public 421302 Shaw, William Martin, farm hand, Orepuki. W arks, W aikiwi, Invercargill. 066560 Shearer, George, quarryman, care of G. Hawkins, \Vinton. 097491 Robertson, James Ian, wool-sorter, Awarua Plains Post 116926 Sheat, Robert Davy, teamster, Moneymore Rural Delivery, office, Southland. Milton. 423543 Robertson, Menzie Athol, labourer, Woodend, Southland.- 253436 Shedden, Allen Miller, coal-trucker, Nightcaps. 298971 Robertson, Robert Alexander, dairy-farmer, Wright's Bush 252526 Sheddan, Maurice, farm labourer, Gore, \Vail,aka Rural Gladfield Rural Delivery, Invercargill. Delivery. 294830 Robertson, Struan Malcolm, labourer, Awarua Plains, 283883 Sheddan, Robert Bruce, farm hand, Scott's Gap, Otautau Southland. Rural Delivery. 431165 Robertson, Tasman Harrie, labourer, 215 Bowmont St., 010254 Sheehan, Walter, general labourer, Te Tipua Rural Delivery, Invercargill. Gore. 247092 Robertson, William Douglas, fisherman, Half-moon Bay, 280428 Sheehan, Walter James, farm hand, Te Tua, Riverton Rural Stewart Island. -

Tuatapere-Community-Response-Plan

NTON Southland has NO Civil Defence sirens (fire brigade sirens are not used as warnings for a Civil Defence emergency) Tuatapere Community Response Plan 2018 If you’d like to become part of the Tuatapere Community Response Group Please email [email protected] Find more information on how you can be prepared for an emergency www.cdsouthland.nz Community Response Planning In the event of an emergency, communities may need to support themselves for up to 10 days before assistance arrives. The more prepared a community is, the more likely it is that the community will be able to look after themselves and others. This plan contains a short demographic description of Tuatapere, information about key hazards and risks, information about Community Emergency Hubs where the community can gather, and important contact information to help the community respond effectively. Members of the Tuatapere Community Response Group have developed the information contained in this plan and will be Emergency Management Southland’s first point of community contact in an emergency. Demographic details • Tuatapere is contained within the Southland District Council area; • The Tuatapere area has a population of approximately 1,940. Tuatapere has a population of about 558; • The main industries in the area include agriculture, forestry, sawmilling, fishing and transportation; • The town has a medical centre, ambulance, police and fire service. There are also fire stations at Orepuki and Blackmount; • There are two primary schools in the area. Waiau Area School and Hauroko Primary School, as well as various preschool options; • The broad geographic area for the Tuatapere Community Response Plan includes lower southwest Fiordland, Lake Hauroko, Lake Monowai, Blackmount, Cliften, Orepuki and Pahia, see the map below for a more detailed indication; • This is not to limit the area, but to give an indication of the extent of the geographic district. -

Water & Atmosphere 19, October 2017

Water & Atmosphere October 2017 When it rains it pours Dealing with sodden seasons No Bluff Tackling the threat of another oyster parasite Great expectations The challenge of setting up automatic weather stations in Vanuatu Cool moves NIWA scientists all aboard for Antarctic study Water & Atmosphere October 2017 Cover: Flooding on Shelly Bay Road, Wellington. (Dave Allen) Water & Atmosphere is published by NIWA. It is available online at www.niwa.co.nz/pubs/wa Enquiries to: In brief The Editor 4 Water & Atmosphere Baby snapper an unexpected prey, marking NIWA makos for mortality, photo ID for dolphins, Private Bag 14901 pine pollen travels far Kilbirnie Wellington 6241 6 News New Zealand WRIBO, phone home: Hi-tech buoy email: [email protected] providing valuable information about ©National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd current, waves and water quality in ISSN 1172-1014 Wellington Harbour Water & Atmosphere team: 16 No Bluff Editor: Mark Blackham Battling oyster pathogens Production: NIWA Communications and Marketing Team Editorial Advisory Board: Geoff Baird, Mark Blackham, Snapped Bryce Cooper, Sarah Fraser, Barb Hayden, Rob Murdoch 26 The best images from NIWA's Instagram account 28 Fire – call NIWA When fire breaks, the Fire Service seeks NIWA's expertise Follow us on: 30 Vagaries of variability facebook.com/nzniwa Fewer, but more intense, tropical cyclones – NIWA's outlook for New Zealand twitter.com/niwa_nz 32 Q&A: Going to sea for fresh water www.niwa.co.nz Searching for an alternative source of water for Wellington 34 Profile: Shoulder to the wheel Water & Atmosphere is produced using vegetable-based inks on Wills Dobson's 'lucky' break paper made from FSC certifed mixed-source fibres under the ISO 14001 environmental management system. -

Middle Earth: Hobbit & Lord of the Rings Tour

MIDDLE EARTH: HOBBIT & LORD OF THE RINGS TOUR 16 DAY MIDDLE EARTH: HOBBIT & LORD OF THE RINGS TOUR YOUR LOGO PRICE ON 16 DAYS MIDDLE EARTH: HOBBIT & LORD OF THE RINGS TOUR REQUEST Day 1 ARRIVE AUCKLAND Day 5 OHAKUNE / WELLINGTON Welcome to New Zealand! We are met on arrival at Auckland This morning we drive to the Mangawhero Falls and the river bed where International Airport before being transferred to our hotel. Tonight, a Smeagol chased and caught a fish, before heading south again across the welcome dinner is served at the hotel. Central Plateau and through the Manawatu Gorge to arrive at the garden of Fernside, the location of Lothlorién in Featherston. Continue south Day 2 AUCKLAND / WAITOMO CAVES / HOBBITON / ROTORUA before arriving into New Zealand’s capital city Wellington, home to many We depart Auckland and travel south crossing the Bombay Hills through the of the LOTR actors and crew during production. dairy rich Waikato countryside to the famous Waitomo Caves. Here we take a guided tour through the amazing limestone caves and into the magical Day 6 WELLINGTON Glowworm Grotto – lit by millions of glow-worms. From Waitomo we travel In central Wellington we walk to the summit of Mt Victoria (Outer Shire) to Matamata to experience the real Middle-Earth with a visit to the Hobbiton and visit the Embassy Theatre – home to the Australasian premieres of Movie Set. During the tour, our guides escorts us through the ten-acre site ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’ and ‘The Two Towers’ and world premiere recounting fascinating details of how the Hobbiton set was created. -

NZFSS Newsletter 51 (2012)

New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society Newsletter Number 51 • December0 | P a g e 2012 ISSN 1177-2026 (print) • ISSN 1178-6906 (online) Contents 1 Introduction to the society .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Editorial .................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 President’s piece .................................................................................................................................... 7 4 He Maimai Aroha – Farewells ................................................................................................................ 9 4 Invited articles and opinion pieces ...................................................................................................... 11 4.1 Prorhynchus putealis: range expansion and call for observations ............................................. 11 4.2 Stealthily slaying the RMA? ......................................................................................................... 14 4.3 A ‘New Deal’ for Fresh Water ..................................................................................................... 15 4.4 A new record for Campbell Island ............................................................................................... 17 4.5 World Class Water and Wildlife .................................................................................................