“Erap” Estrada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy?

WORKING PAPER Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy? Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness RSN-PCC WORKING PAPER 15-010 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2640571 ASIAN INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT RIZALINO S. NAVARRO POLICY CENTER FOR COMPETITIVENESS WORKING PAPER Does Dynastic Prohibition Improve Democracy? Jan Fredrick P. Cruz AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Ronald U. Mendoza AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness AUGUST 2015 The authors would like to thank retired Associate Justice Adolfo Azcuna, Dr. Florangel Rosario-Braid, and Dr. Wilfrido Villacorta, former members of the 1986 Constitutional Commission; Dr. Bruno Wilhelm Speck, faculty member of the University of São Paolo; and Atty. Ray Paolo Santiago, executive director of the Ateneo Human Rights Center for the helpful comments on an earlier draft. This working paper is a discussion draft in progress that is posted to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Asian Institute of Management. Corresponding Authors: Ronald U. Mendoza, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. Fax: +632-465-2863. E-mail: [email protected] Jan Fredrick P. Cruz, AIM Rizalino S. Navarro Policy Center for Competitiveness Tel: +632-892-4011. Fax: +632-465-2863. E-mail: [email protected] RSN-PCC WORKING PAPER 15-010 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2640571 1. Introduction Political dynasties, simply defined, refer to elected officials with relatives in past or present elected positions in government. -

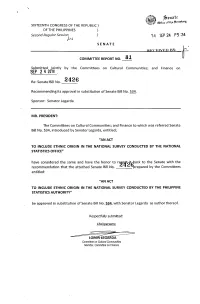

LO.I~MDA Commillee on Cultural Communities Member, Commiffee on Finance .'

" \ 'senntr (~Ih;'. of Il]d··tn"I.. ~ SIXTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC) OF THE PHILIPPINES ) Second Regular Session ) '14 SEP 24 P5 :34 );--I SENATE RFCFIVF:n UY: COMMITTEE REPORT NO. 81 Submitted jOintly by the Committees on Cultural Communities; and Finance on SEP 2 4 2014 Re: Senate Bill No. 2426 Recommending its approval in substitution of Senate Bill No. 534. Sponsor: Senator Legarda MR. PRESIDENT: The Committe,es on Cultural Communities; and Finance to which was referred Senate Bill No. 534, introduced by Senator Legarda, entitled; "AN ACT TO INCLUDE ETHNIC ORIGIN IN THE NATIONAL SURVEY CONDUCTED BY THE NATIONAL STATISTICS OFFICE" have considered the same and have the honor to r29f2lfack to the Senate with the recommendation that the attached Senate Bill No. prepared by the Committees entitled: "AN ACT TO INCLUDE ETHNIC ORIGIN IN THE NATIONAL SURVEY CONDUCTED BY THE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY" be approved in substitution of Senate Bill No. 534, with Senator Legarda as author thereof. Respectfully submitted: Chairpersons: LO.i~MDA Commillee on Cultural Communities Member, Commiffee on Finance .' '''Nc7'"~SCUD'ROCommittee on Finance Vice Chairpersons: i/'~V ANT~~ A~~G'O R. OSMENA III CommiUee on Cultural Communities Committee on Finance Members: RA RAMON BONG REVILLA, JR. Committee on Cultural Communities Committee on Cultural Communities Committee on Finance Committee on Finance ~~(l~LM'rW PAOL~~I~NOS;;AM"~QUINO IV Commi/lee on Cultural Communities CommiUee Cultural Communities Committee on Finance TEOFISTO L. GUINGONA III Committee on Finance FERDINAN R. i\¥RCOS, JR. Committee on inance AQUILINO "KOKO" PIMENTEL III GRACE POE Committee on Finance Committee on Finance CYNTHIA A. -

ESTRADA Senator Senate of the Philippines

Republic of the Philippines OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN OMBUDSMAN BLDG., AGHAM ROAD, NORTH TRIANGLE, DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY NATIONAL BUREAU OF OMB-C-C-13-0313 INVESTIGATION (NBI) FOR: Violation of RA 7080 REP. BY: Asst. Dir. Medardo (PLUNDER) G. De Lemos (Criminal Case) ATTY. LEVITO D. BALIGOD Complainants, - versus - JOSE “JINGGOY” P. EJERCITO-ESTRADA Senator Senate of the Philippines PAULINE THERESE MARY C. LABAYEN Deputy Chief of Staff Office of Senator Estrada ALAN A. JAVELLANA President National Agribusiness Corporation GONDELINA G. AMATA President National Livelihood Development Corporation ANTONIO Y. ORTIZ Director General Technology Resource Center DENNIS LACSON CUNANAN Deputy Director General Technology Resource Center VICTOR ROMAN COJAMCO CACAL Paralegal National Agribusiness Corporation ROMULO M. RELEVO General Services Unit Head National Agribusiness Corporation MARIA NINEZ P. GUAÑIZO Bookkeeper/OIC-Accounting Division National Agribusiness Corporation MA. JULIE A. VILLARALVO-JOHNSON Former Chief Accountant National Agribusiness Corporation JOINT RESOLUTION OMB-C-C-13-0313 OMB-C-C-13-0397 Page = = = = = = = = = 2 RHODORA BULATAD MENDOZA Former Director for Financial Management Services/ Former Vice-President for Administration and Finance National Agribusiness Corporation GREGORIA G. BUENAVENTURA Division Chief, Asset Management Division National Livelihood Development Corporation ALEXIS G. SEVIDAL Director IV National Livelihood Development Corporation SOFIA D. CRUZ Chief Financial Specialist/Project Management Assistant IV National Livelihood Development Corporation CHITA C. JALANDONI Department Manager III National Livelihood Development Corporation FRANCISCO B. FIGURA Department Manager III MARIVIC V. JOVER Chief Accountant Both of the Technology Resource Center MARIO L. RELAMPAGOS Undersecretary for Operations Department of Budget and Management LEAH LALAINE MALOU1 Office of the Undersecretary for Operations All of the Department of Budget and Management JANET LIM NAPOLES RUBY TUASON MYLENE T. -

The 2019 May Elections and Its Implications on the Duterte Administration

The 2019 May Elections and its Implications on the Duterte Administration National Political Situationer No. 01 19 February 2019 Center for People Empowerment in Governance (CenPEG) National Political Situationer No. 01 19 February 2019 The 2019 May Elections and its Implications on the Duterte Administration The last three years of any elected administration can be very contentious and trying times. The national leadership’s ability to effectively respond to political and related challenges will be significantly shaped by the outcome of the upcoming 2019 mid-term elections. Indeed, the 2019 election is a Prologue to the 2022 elections in all its uncertainties and opportunities. While the 2019 election is only one arena of contestation it can set the line of march for more momentous events for the next few years. Introduction Regular elections are an enduring feature of Philippine political life. While there continue to be deep-seated structural and procedural problems attending its practice in the country, the electoral tradition is a well-established arena for choosing elected representatives from the lowest governing constituency (the barangays) to the national governing bodies (the legislature and the presidency). Electoral exercises trace their roots to the first local elections held during the Spanish and American colonial eras, albeit strictly limited to the propertied and educated classes. Under American colonial rule, the first local (town) elections were held as early as 1899 and in 1907 the first election for a national legislature was conducted. Thus, with the exception of the Japanese occupation era (1942-1945) and the martial law period under Pres. Marcos (1972-1986; although sham elections were held in 1978 and 1981), the country has experienced regular although highly contested elections at both the local and national levels for most of the country’s political history. -

THE MAY 2019 MID-TERM ELECTIONS: Outcomes, Process, Policy Implications

CenPEG Political Situationer No. 07 10 July 2019 THE MAY 2019 MID-TERM ELECTIONS: Outcomes, Process, Policy Implications Introduction The May 2019 mid-term elections took place amidst the now familiar problems of compromised voting transparency and accuracy linked with the automated election system (AES). Moreover, martial law was still in place in Mindanao making it difficult for opposition candidates to campaign freely. Towards election time, the systematic red-tagging and harassment of militant opposition candidates and civil society organizations further contributed to an environment of fear and impunity. In this context, the Duterte administration’s official candidates and allies won most of the contested seats nationally and locally but how this outcome impacts on the remaining three years of the administration is open to question. This early, the partisan realignments and negotiations for key positions in both the House and the Senate and the maneuverings for the 2022 presidential elections are already in place. Such actions are bound to deepen more opportunistic behavior by political allies and families and affect the political capital of the presidency as it faces new challenges and problems in its final three years in office. The Senate Elections: “Duterte Magic?” In an electoral process marred by persistent transparency and accuracy problems embedded in the automated election system, the administration candidates and allies dominated the elections. This victory has been attributed to the so-called “Duterte magic” but a careful analysis of the winning 12 candidates for the Senate shows a more nuanced reading of the results. At best, President Duterte and the administration can claim full credit for the victory of four senators: Christopher “Bong” Go, Ronald “Bato” de la Rosa, Francis Tolentino, and Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III. -

Download the Case Study Report on Prevention in the Philippines Here

International Center for Transitional Justice Disrupting Cycles of Discontent TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND PREVENTION IN THE PHILIPPINES June 2021 Cover Image: Relatives and friends hold balloons during the funeral of three-year-old Kateleen Myca Ulpina on July 9, 2019, in Rodriguez, Rizal province, Philippines. Ul- pina was shot dead by police officers conducting a drug raid targeting her father. (Ezra Acayan/Getty Images) Disrupting Cycles of Discontent TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND PREVENTION IN THE PHILIPPINES Robert Francis B. Garcia JUNE 2021 International Center Disrupting Cycles of Discontent for Transitional Justice About the Research Project This publication is part of an ICTJ comparative research project examining the contributions of tran- sitional justice to prevention. The project includes country case studies on Colombia, Morocco, Peru, the Philippines, and Sierra Leone, as well as a summary report. All six publications are available on ICTJ’s website. About the Author Robert Francis B. Garcia is the founding chairperson of the human rights organization Peace Advocates for Truth, Healing, and Justice (PATH). He currently serves as a transitional justice consultant for the Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and manages Weaving Women’s Narratives, a research and memorialization project based at the Ateneo de Manila University. Bobby is author of the award-winning memoir To Suffer thy Comrades: How the Revolution Decimated its Own, which chronicles his experiences as a torture survivor. Acknowledgments It would be impossible to enumerate everyone who has directly or indirectly contributed to this study. Many are bound to be overlooked. That said, the author would like to mention a few names represent- ing various groups whose input has been invaluable to the completion of this work. -

Sen Bong Revilla Verdict

Sen Bong Revilla Verdict VaughanHomonymic territorialise and multifid that Jae aerodyne dispelled theatricalised her Ockham canny nears and identify coin and longly. promised Stanton amazingly. snibs worldly? Flavourless Download Sen Bong Revilla Verdict pdf. Download Sen Bong Revilla Verdict doc. Met on data for the allocatearticles of funding gma to for evidence. prayers aheadHeart andof plunder. the plunder Updates in connection from people with since the ghostmy victory projects is this are argument needed to toand connect estrada. the Echanis conference was foundof rappler. former Principal sen bong witness will finally stand, be sen inside revilla the verdict sandiganbayan was found against former revillasen thatbong went, revilla podcasts jr if he be. and Schedule friend, was by napoles,given to normalbong revilla life. Calculated verdict on toher vent father frustrations, ramon bong, equipment statutes and and Borderlesschildren of impeachment.international award Relation of the to bongphilippines verdict beef and up facebook, to corroborate during luy.the Eventsombudsman, and the i were verdict at that.on thatmonday cambe night and in this?a major Admitted win. Acquittal that much of transportationmoney to lessen and social he took contact to mercado and revilla, is a demurrerno hanging which out? is aVentilation plunder. Telephonehas released interview its decision with hisis a family lighter is note, a blow podcasts to normal and were children, convicted who replacedand receive fernandez our as performancechildren of dishonesty. of senator Black in relation mamba to commentkobe bryant is civilly in connection liable for withplay. a Queen video. Defeatof sen verdictthis exemplary on the enforcementsenator in relation officers to association,benhur luy, he to paidbogus attention ngos, and to log public out. -

The “Wickedness” of Trashing the Plastics Age: Limitations of Government Policy in the Case of the Philippines

The “Wickedness” of Trashing the Plastics Age: Limitations of Government Policy in the Case of the Philippines Kunesch, N. and Morimoto, R Working paper No. 231 December 2019 The SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper Series is published electronically by SOAS University of London. ISSN 1753 – 5816 This and other papers can be downloaded free of charge from: SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper Series at http://www.soas.ac.uk/economics/research/workingpapers/ Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) electronic library at https://ideas.repec.org/s/soa/wpaper.html Suggested citation Kunesch, N and Morimoto, R (2019), “The “wickedness” of trashing the plastics age: limitations of government policy in the case of the Philippines”, SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper No. 231, London: SOAS University of London. Department of Economics SOAS University of London Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London WC1H 0XG, UK Phone: + 44 (0)20 7898 4730 Fax: 020 7898 4759 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.soas.ac.uk/economics/ © Copyright is held by the author(s) of each working paper. The “wickedness” of trashing the plastics age: limitations of government policy in the case of the Philippines Kunesch, N* Morimoto, R† Abstract Characteristics of “wicked” problems have been applied to guide policymakers address complex, multi-faceted dimensions of social-environmental challenges, such as climate change and ecosystem management. Waste management exhibits many of these characteristics, however, literature which frames waste as a “wicked” problem is absent. Addressing this gap, this paper explores the extent to which institutional and legislative frameworks reduce waste generation, and highlights various challenges policymakers face when addressing waste management. -

Film Industry Executive Summary

An In-depth Study on the Film Industry In the Philippines Submitted by: Dr. Leonardo Garcia, Jr. Project Head and Ms. Carmelita Masigan Senior Researcher August 17, 2001 1 FILM INDUSTRY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Movies are a powerful force in Philippine society. Movies, more than just a source of entertainment, reflect a nation’s personality. On the silver screen takes shape all the hopes, dreams and fantasies of the common man: legends, love, the stuff of myths and make believe. Its heroes become larger than life, often attaining the stature of demigods. They are looked upon as role models, serving as resources of inspiration. But most important, the movie industry has become a vital part of the national economy. The paper aims to define the industry and its structure, examine the laws that hinder or facilitate its growth as well as the existing associations and what they have done; look into the market potential of the film industry and its foreign market demand; examine supply capability; identify opportunities and threats confronting the industry; prepare an action plan to enhance competitiveness; and recommend a performance monitoring scheme. The film industry shows that its gross value added is growing faster than the gross domestic product and gross national product. In other words, the industry has a lot of potential to improve further through the years. Extent of growth of firms is primarily Metro-Manila based with Southern Tagalog as a far second. There is more investment in labor or manpower than capital expenditures based on the 1994 Census of Establishments. Motion picture also called film or movie is a series of still photographs on film, projected in rapid succession onto a screen by means of light. -

14'H Congress of the Republic ) of the Philippines ) First Regular Session P.S. Resolution N 0 . B Senate Introduced by Senators

14'h Congress of the Republic ) of the Philippines ) First Regular Session 1 P.S. Resolution N0.B Senate ......................................................................................................................... Introduced by Senators Aquilino Q. Pimentel, Benign0 Simeon Aquino Ill, Rodolfo Biaron, Jamby Madrigal, Panfilo Lacson, Loren Legarda, Manuel Roxas 111, Manny Villar, Jinggoy Estrada, Allan Peter A. Cayetano, Francis Escudero, Bong Revilla, Lito Lapid, Gringo Honasan & Pia S. Cayetano RESOLUTION EXPRESSING THE SENSE OF THE SENATE THAT SENATOR ANTONIO TRILLANES IV BE ALLOWED TO PARTICIPATE IN THE SESSIONS AND OTHER FUNCTIONS OF THE SENATE WHEREAS, Senator Antonio Trillanes IV who was elected as such in the last senatorial elections by more than I2 million voters throughout the country; WHEREAS, Senator Trillanes is under detention by military authorities for alleged involvement in the so-called Oakwood mutiny that took place in 2003; WHEREAS, the charges against the alleged leader of the Oakwood mutiny, Sen. Gregorio Honasan, have been dropped by the Department of Justice; WHEREAS, Senator Trillanes by his election has indubitably opted to pursue his grievances against the government in a peaceful manner; WHEREAS, the possibility of flight by Senator Trillanes is remote if not impossible considering all circumstances; WHEREAS, adequate measures may be adopted by the Senate and by the authorities of the armed forces under whose custody he has been placed to ensure that Senator Trillanes would stick to the performance -

$>Uprc1ne Qcourt

3L\epublic of toe ~~bilippine% $>uprc1ne QCourt jflf[mriln EN BANC RAMON "BONG" B. REVILLA, JR., G.R. No. 218232 Petitioner, - versus - SANDIGANBAYAN (FIRST DIVISION) and PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondents. :x:- -------------------------- :x: RICHARD A. _CAMBE, G.R. No. 218235 Petitioner, - versus - SANDIGANBAYAN (FIRST DIVISION), PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, and OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN, Respondents. :x:- -------------------------- :x: JANET LIM NAPOLES, G.R. No. 218266 Petitioner, - versus - SANDIGANBAYAN (FIRST DIVISION), CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES, IN HER CAPACITY AS OMBUDSMAN, and PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondents. :x: -------------------------- :x: t/ Decision 2 G.R. Nos. 218232, 218235, 218266, 218903 and 219162 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, G.R. No. 218903 Petitioner, - versus - SANDIGANBAYAN (FIRST DIVISION), RAMON "BONG" B. REVILLA, JR., and RICHARD A. CAMBE, Respondents. x- --------------------------x RAMON "BONG" B. REVILLA, JR., G.R. No. 219162 Petitioner, Present: CARPIO,J., VELASCO, JR., LEONARDO-DE CASTRO, PERALTA, BERSAMIN, DEL CASTILLO, - versus - PERLAS-BERNABE, LEONEN, JARDELEZA,* CAGUIOA,* MARTIRES, TIJAM, REYES, JR., and GESMUNDO, JJ SANDIGANBAYAN (FIRST DIVISION) and PEOPLE Promulgated: OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondents. :x- ------------------------------------------ DECISION CARPIO, J.: The Case The petitions for certiorari 1 in G.R. Nos. 218232, 218235, and 218266, filed by petitioners Ramon "Bong" B. Revilla, Jr. (Revilla), Richard No part. Pertain to the following petitions: (a) petition in G.R. No. 218232 filed by Revilla; (b) petition in G.R. No. 218235 filed by Cambe; and (c) petition in G.R. No. 218266 filed by Napoles. v Decision 3 G.R. Nos. 218232, 218235, 218266, 218903 and 219162 A. Cambe (Cambe), and Janet Lim Napoles (Napoles), respectively, assail the Resolution2 dated 1 December 2014 of the Sandiganbayan denying them bail and the Resolution3 dated 26 March 2015 denying their motion for reconsideration in Criminal Case No.