The Quest for Ultimate Reality | Frontline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr.K.G.Asha Manjari

DR.K.G.ASHA MANJARI PROFESSOR Department of studies in Earth science Centre for Advanced study in Precambrian Geology University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Mysore-570 006 [email protected] +91-9448600554 ADDRESS Office Dept. of Studies in Earth science, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Mysore- 570 006, Karnataka, INDIA. +91-821-2419721, Mob: +91-9448600554 E-mail: [email protected] Residential 10/B, SPARSHA, 2nd Main, 2nd Cross, Bogadhi IInd Stage MYSORE-570 026, Karnataka, INDIA. ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION: Bachelor of science, University of Mysore, Mysore, India- 1981 Master of science, University of Mysore, Mysore, India-First Rank-1983 Doctor of Philosophy, University of Mysore, Mysore, India-1989 Recipient of Mysore University Padmamma Salighrama Gold Medal and Prof. Nikkam’s Science Rotation Gold Medal in M.Sc.-1983 Young Scientist Travel Grant from DST and CSIR to attend IGCP 301at USA in 1992 Visiting Scientist at Rice University, Houston, USA 1992. Recipient of Young Scientist Research Project from DST 1994. Recipient of Prof. Satish Dhawan Young Scientist Award from KSCST, Government of Karnataka in 2006 Recipient of Bharat Jyoti Award from India International Friendship Society, New Delhi 2012 TITLE OF THE DOCTORAL THESIS Chemical Petrology of the Granulite and other associated rock types around Nilgiri hills Tamilnadu, India. VISITS ABROAD: USA, Sri Lanka , Singapore and China TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Twenty-six years to Post-graduate (Geology, Applied Geology & Earth Science & Resource Management) Guiding students for Ph.D degree. Successfully guided students for Minor and Major (dissertation work) Projects. MEMBERSHIP OF PROFESSIONAL BODIES Life Fellow and member of advisory committee of Mineralogical Society of India. -

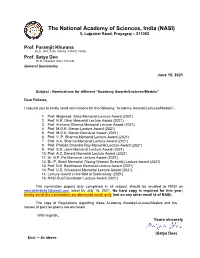

Nominations for Different “Academy Awards/Lectures/ Medals”

The National Academy of Sciences, India (NASI) 5, Lajpatrai Road, Prayagraj – 211002 Prof. Paramjit Khurana Ph.D., FNA, FASc, FNAAS, FTWAS, FNASc Prof. Satya Deo Ph.D. (Arkansas, USA), F.N.A.Sc. General Secretaries June 15, 2021 Subject : Nominations for different “Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals” Dear Fellows, I request you to kindly send nominations for the following “Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals”– 1. Prof. Meghnad Saha Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 2. Prof. N.R. Dhar Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 3. Prof. Archana Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 4. Prof. M.G.K. Menon Lecture Award (2021) 5. Prof. M.G.K. Menon Memorial Award (2021) 6. Prof. V. P. Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 7. Prof. A.K. Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 8. Prof. Prafulla Chandra Ray Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 9. Prof. S.K. Joshi Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 10. Prof. A.C. Banerji Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 11. Dr. B.P. Pal Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 12. Dr. P. Sheel Memorial (Young Women Scientist) Lecture Award (2021) 13. Prof. B.K. Bachhawat Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 14. Prof. U.S. Srivastava Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 15. Lecture Award in the field of Biodiversity (2021) 16. NASI-Buti Foundation Lecture Award (2021) The nomination papers duly completed in all respect should be emailed to NASI on [email protected] latest by July 15, 2021. No hard copy is required for this year; kindly send the nomination on aforesaid email only (not on any other email id of NASI). The copy of Regulations regarding these Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals and the names of past recipients are enclosed. -

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

Another Global History of Science: Making Space for India and China

BJHS: Themes 1: 115–143, 2016. © British Society for the History of Science 2016. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/bjt.2016.4 First published online 22 March 2016 Another global history of science: making space for India and China ASIF SIDDIQI* Abstract. Drawing from recent theoretical insights on the circulation of knowledge, this article, grounded in real-world examples, illustrates the importance of ‘the site’ as an analytical heur- istic for revealing processes, movements and connections illegible within either nation-centred histories or comparative national studies. By investigating place instead of project, the study reframes the birth of modern rocket developments in both China and India as fundamentally intertwined within common global networks of science. I investigate four seemingly discon- nected sites in the US, India, China and Ukraine, each separated by politics but connected and embedded in conduits that enabled the flow of expertise during (and in some cases despite) the Cold War. By doing so, it is possible to reconstruct an exemplar of a kind of global history of science, some of which takes place in China, some in India, and some else- where, but all of it connected. There are no discrete beginnings or endings here, merely points of intervention to take stock of processes in action. Each site produces objects and knowledge that contribute to our understanding of the other sites, furthering the overall narra- tive on Chinese and Indian efforts to formalize a ‘national’ space programme. -

Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST) NEWSLETTER Vol.4, No.1, January 2019

Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST) NEWSLETTER www.iist.ac.in Vol.4, No.1, January 2019 Director’s Message th Greetings! 6 IIST Convocation I am delighted to announce the re-launch of Indian Institute of Space Dr. V K Dadhwal, Director IIST's News Letter from January 2019. This Science and Technology (IIST) and Chairman BoM, IIST task has been assigned to a new Newsletter th conducted its 6 convocation along with Deans, Senior Committee which will regularly bringing on 18 t h July 2018 at Dr. Professors and Heads of the out two issues annually to share and widely Srinivasan Auditorium, VSSC. Departments. Dr. B N Suresh, circulate on the important events at the The convocation started at Chancellor, IIST opened the institute. Featured in the current issue are the 14.00 hrs with the academic convocation proceedings. host of activities and happenings at the procession led by Prof. A institute during 1st July 2018 to 31st December Chandrasekar, Registrar, IIST th and was joined by Dr. B N Dr. V K Dadhwal, Director 2018. Highlights of the issue include the 6 and Chairman, BoM, IIST in convocation held on 18th July 2018, Dr. Abdul Suresh, Chancellor, IIST, Dr. K S i v a n , C h a i r m a n , h i s w e l c o m e s p e e c h Kalam Lecture, Foundation day celebration, Governing Council, IIST, e l a b o r a t e d o n t h e International and National conferences, Chairman ISRO and Secretary achievements of IIST over the Seminars and workshops organised by us. -

IISER AR PART I A.Cdr

dm{f©H$ à{VdoXZ Annual Report 2016-17 ^maVr¶ {dkmZ {ejm Ed§ AZwg§YmZ g§ñWmZ nwUo Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Pune XyaX{e©Vm Ed§ bú` uCƒV‘ j‘Vm Ho$ EH$ Eogo d¡km{ZH$ g§ñWmZ H$s ñWmnZm {Og‘| AË`mYw{ZH$ AZwg§YmZ g{hV AÜ`mnZ Ed§ {ejm nyU©ê$n go EH$sH¥$V hmo& u{Okmgm Am¡a aMZmË‘H$Vm go `wº$ CËH¥$ï> g‘mH$bZmË‘H$ AÜ`mnZ Ho$ ‘mÜ`m‘ go ‘m¡{bH$ {dkmZ Ho$ AÜ``Z H$mo amoMH$ ~ZmZm& ubMrbo Ed§ Agr‘ nmR>çH«$‘ VWm AZwg§YmZ n[a`moOZmAm| Ho$ ‘mÜ`‘ go N>moQ>r Am`w ‘| hr AZwg§YmZ joÌ ‘| àdoe& Vision & Mission uEstablish scientific institution of the highest caliber where teaching and education are totally integrated with state-of-the-art research uMake learning of basic sciences exciting through excellent integrative teaching driven by curiosity and creativity uEntry into research at an early age through a flexible borderless curriculum and research projects Annual Report 2016-17 Correct Citation IISER Pune Annual Report 2016-17, Pune, India Published by Dr. K.N. Ganesh Director Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Pune Dr. Homi J. Bhabha Road Pashan, Pune 411 008, India Telephone: +91 20 2590 8001 Fax: +91 20 2025 1566 Website: www.iiserpune.ac.in Compiled and Edited by Dr. Shanti Kalipatnapu Dr. V.S. Rao Ms. Kranthi Thiyyagura Photo Courtesy IISER Pune Students and Staff © No part of this publication be reproduced without permission from the Director, IISER Pune at the above address Printed by United Multicolour Printers Pvt. -

6 Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Lecture Legion D'honneur' (2002) by the President of the French Republic, France

About the Speaker Dr Krishnaswamy Kasturirangan completed his BSc with Honours and MSc in Physics from Bombay University and received his Doctorate in Experimental High Energy Astronomy in 1971. His interests include astrophysics, space science and technology as well as science related policies. भारतीय अतं र वान एवं ौयोगक संथान Dr Kasturirangan was with the ISRO for over a period of nearly 35 years including nearly 10 years Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology as its Chairman from 1994-2003. He was a Member, Rajya Sabha (2003-2009) and concurrently the वलयमला, तवनंतपरम Director of NIAS, Bangalore. He served as a Member of the erstwhile Planning Commission (2009- ु Valiamala, Thiruvananthapuram 2014). Dr Kasturirangan served the Karnataka Knowledge Commission as its Chairman and was entrusted as the Chairman of the Committee for drafting the new National Education Policy. Presently he is the Chairman, Governing Board, IUCAA, Pune; Chancellor, Central University of Rajasthan; Chairperson, NIIT University, Neemrana; Member, Atomic Energy Commission; Emeritus Professor at NIAS, Bangalore and Honorary Distinguished Advisor, ISRO. Dr Kasturirangan is a Member of several International and National Science Academies. He is a Member of the International Astronomical Union, Fellow of TWAS, Honorary Fellow of the Cardiff University, UK and Academician of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Vatican City. Dr Kasturirangan is the only Indian to be conferred the Honorary Membership of the International Academy of Astronautics. Dr Kasturirangan was the first to occupy the Satish Dhawan Chair of Engineering Eminence (2015- 2017). He also occupied as the Chairman, BG, IIT, Chennai (2000-2005), Chairman, Council, IISc, Bangalore (2004-2015), Chancellor, JNU, New Delhi (2012-17), Chairman, Council, RRI, Bangalore (2000-2016). -

Handbook 2018-19

FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY Handbook 2018-19 SRM Nagar, Kattankulathur - 603 203 Kancheepuram District, Tamilnadu Telephone: 044- 27417499, 27417000 Fax: 044-27453903 URL: www.srmuniv.ac.in “Motivation gets you going, but, Discipline keeps you growing.” — John C. Maxwell Best Wishes for a Productive and Enjoyable Academic Year 2018–19 PERSONAL MEMORANDA 1. NAME : ________________________ 2. REGISTER NO. : ________________________ 3. YEAR & COURSE : ________________________ 4. BRANCH / SECTION : ________________________ 5. HOSTEL BLOCK & ROOM NO. : ________________________ 6. BUS PASS NO. : ________________________ 7. TRAIN PASS NO. : ________________________ 8. AADHAR CARD NO. : ________________________ 9. ADDRESS FOR COMMUNICATION : ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ 10. PERMANENT ADDRESS : ________________________ : ________________________ : ________________________ 11. MOBILE NO. : ________________________ 12. E-MAIL ID : ________________________ 13. DATE OF BIRTH : ________________________ 14. BLOOD GROUP : ________________________ 15. HEIGHT & WEIGHT : ________________________ 16. IDENTIFICATION MARKS : ________________________ FROM THE CHANCELLOR SRM Institute of Science and Technology engineering programs endeavor to be at the forefront of innovation. They also foster multi-disciplinary collaborations aimed at solving the most pressing global problems. Our mission is to seek solutions to global challenges by using the power of engineering principles, techniques and systems. We -

Satish Dhawan

CORRESPONDENCE Satish Dhawan The Special Section in Current Science, minded the Cabinet of the pending Committee (ICC) were SD’s initiatives 2020, 119(9), 1417–1488, celebrating the INSAT-I proposal. Instead of asking the and management innovations. SD’s pres- birth centenary of Satish Dhawan (SD), then post-election inactive main group, entation style ‘Red Book’, in A4-size the first Chairman of the Space Commis- the Cabinet, while approving APPLE landscape-orientation, on his group’s re- sion and Secretary, Department of Space investment, asked DoS to bring up the port and recommendations to the main (DoS), Government of India, besides INSAT-I proposal within a month. This group on INSAT-I is a classic document; several other leadership roles that he had was obviously facilitated by the ‘last ahead of its times in a style, that would played in institutions like the Indian In- ICS’ Cabinet Secretary Nirmal Mukher- later be generically known as a ‘power stitute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, that jee, who as Secretary Civil Aviation – point’ presentation. he headed, served, guided or set-up, is a under which Ministry IMD was then – Another important step for the imple- collector’s item. had got to understand the transformative mentation and oversight of the multi- Here, I would like to add an under- role and function of INSAT while partic- agency INSAT project was the creation recognized dimension to the seminal and ipating actively in the SD-led INSAT-I of the unique INSAT Coordination defining role that SD played in so many System Definition Sub-Group of Secreta- Committee of Secretaries chaired by Sec- aspects of satellite-based services for ries. -

513691 Journal of Space Law 35.1.Ps

JOURNAL OF SPACE LAW VOLUME 35, NUMBER 1 Spring 2009 1 JOURNAL OF SPACE LAW UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI SCHOOL OF LAW A JOURNAL DEVOTED TO SPACE LAW AND THE LEGAL PROBLEMS ARISING OUT OF HUMAN ACTIVITIES IN OUTER SPACE. VOLUME 35 SPRING 2009 NUMBER 1 Editor-in-Chief Professor Joanne Irene Gabrynowicz, J.D. Executive Editor Jacqueline Etil Serrao, J.D., LL.M. Articles Editors Business Manager P.J. Blount Michelle Aten Jason A. Crook Michael S. Dodge Senior Staff Assistant Charley Foster Melissa Wilson Gretchen Harris Brad Laney Eric McAdamis Luke Neder Founder, Dr. Stephen Gorove (1917-2001) All correspondence with reference to this publication should be directed to the JOURNAL OF SPACE LAW, P.O. Box 1848, University of Mississippi School of Law, University, Mississippi 38677; [email protected]; tel: +1.662.915.6857, or fax: +1.662.915.6921. JOURNAL OF SPACE LAW. The subscription rate for 2009 is $100 U.S. for U.S. domestic/individual; $120 U.S. for U.S. domestic/organization; $105 U.S. for non-U.S./individual; $125 U.S. for non-U.S./organization. Single issues may be ordered at $70 per issue. For non-U.S. airmail, add $20 U.S. Please see subscription page at the back of this volume. Copyright © Journal of Space Law 2009. Suggested abbreviation: J. SPACE L. ISSN: 0095-7577 JOURNAL OF SPACE LAW UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI SCHOOL OF LAW A JOURNAL DEVOTED TO SPACE LAW AND THE LEGAL PROBLEMS ARISING OUT OF HUMAN ACTIVITIES IN OUTER SPACE. VOLUME 35 SPRING 2009 NUMBER 1 CONTENTS Foreword .............................................. -

Govind Swarup: Radio Astronomer, Innovator Par Excellence and a Wonderfully Inspiring Leader

LIVING LEGENDS IN INDIAN SCIENCE Govind Swarup: Radio astronomer, innovator par excellence and a wonderfully inspiring leader G. Srinivasan They are ill discoverers that think there the important contributions to cosmology is no land, when they can see nothing but being made using this telescope. He sea. mentioned in very flattering terms the Francis Bacon Ph D thesis of one of Swarup’s students (Vijay Kapahi) which had come to him I must say at the outset that I have no for evaluation. That is how I came to special credentials to write an article know of Swarup. about as famous a person as Govind As it turned out, I moved from Cam- Swarup. I am not one of his numerous bridge to the Raman Research Institute students. Nor have I collaborated with (RRI), Bangalore in the beginning of him in research. Indeed, I am not even an 1976. Within weeks after my coming, I astronomer, let alone a radio astronomer. received an invitation from Govind Swa- But I have been one of his great admir- rup to attend a small meeting he had ers, and he has been a beacon of inspira- convened at RRI to discuss a Summer tion for me during the past four decades. School in Astronomy he was organizing I was therefore delighted – although sur- in Bangalore in June 1976. I was rather prised – when the Editor of Current Sci- surprised because I was still working in ence invited me to write this article. The Condensed Matter Physics. There were K. S. Krishnan, B. N. -

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Important Awards and Honours Winner Prize Awarded By/Theme/Purpose Hyderabad International CII - GBC 'National Energy Carbon Neutral Airport having Level Airport Leader' and 'Excellent Energy 3 + "Neutrality" Accreditation from Efficient Unit' award Airports Council International Roohi Sultana National Teachers Award ‘Play way method’ to teach her 2020 students Air Force Sports Control Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Air Marshal MSG Menon received Board Puruskar 2020 the award NTPC Vallur from Tamil Nadu AIMA Chanakya (Business Simulation Game)National Management Games(NMG)2020 IIT Madras-incubated Agnikul TiE50 award Cosmos Manmohan Singh Indira Gandhi Peace Prize On British broadcaster David Attenborough Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Best Screenplay award at Earlier, it was honoured with the Disciple Venice International Film International Critics’ Prize awarded Festival by FIPRESCI. Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland Golden Lion award at Venice International Film Festival Aditya Puri (MD, HDFC Bank) Lifetime Achievement Award Euromoney Awards of Excellence 2020. Margaret Atwood (Canadian Dayton Literary Peace Prize’s writer) lifetime achievement award 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB PO Mains 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB Clerk Mains 2020 Follow us: Telegram , Facebook , Twitter , Instagram 1 Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Rome's Fiumicino Airport First airport in the world to Skytrax (Leonardo