Recovery and Current Status of Seabirds on the Baja California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atoll Research Bulletin

0-v Nos. 12, 13, 14 December 15, 1952 ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 12 Preliminary Report on Geology and Marine Environments of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands by Preston E. Cloud, Jr. 13. Preliminary Report on Marine Biology Study of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands by A. H. Banner and J. E. Randall ^ 14. Description of Kayangel Atoll, Palau Islands by J. L. Gressitt m^^m Issued by THE PACIFIC SCIENCE BOARD National Academy of Sciences—^National Research Council Washington, D. C, U.S.A. ATOLL RESGLbRCII BUILETIIJ 12. Preliminarj'" Report on Geo2.og^' and Mo.rine Environnients of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands hy Preston E. G3.oud, Jr. 13. Preljjninary Report on Marine Biology Study of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands by A. H. Banner and J. E. Randall 14. Description of Kayangel Atoll, Palau Islands by J. L. Gressitt Issued by THE PACIFIC SCIENCE BOARD National Academy of vSciences—National Research Council Washington, D.C. December 15, 1952 . ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN No. U Description of. Keyangel Atoll, Palau Islands by J. L. Gressitt Issued by THE PACIFIC SGIEi^CE BOARD National Academy of Sciences—National Research Council Washington , D . C December 15, 1952 DESCRIPTION OF KAYANGEL ATOLL, PALAU ISLANDS By J. L. Gressitt Pacific Science Board , Kayangel Atoll is the northernmost land area of the Palau Archipelago in the western Caroline Islands, except for Ngaruangl, a sand bank on an incipient atoll to its north. There are no other atolls v/ithin 150 miles. Kaj'-angel is separated from Babelthuap, the largest island of the Palatis and a volcanic is- land, by about tv/enty miles of water. -

This Keyword List Contains Indian Ocean Place Names of Coral Reefs, Islands, Bays and Other Geographic Features in a Hierarchical Structure

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 8/9/2016 Indian Ocean This keyword list contains Indian Ocean place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. For example, the first name on the list - Bird Islet - is part of the Addu Atoll, which is in the Indian Ocean. The leading label - OCEAN BASIN - indicates this list is organized according to ocean, sea, and geographic names rather than country place names. The list is sorted alphabetically. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Indian Ocean” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. For example, the first place name “Bird Islet” has a unique identifier of “00S073E0013”. From that we see that Bird Islet is located at 00 degrees south (S) and 073 degrees east (E). It is place number 0013 at that latitude and longitude. (Note: some long lines wrapped, placing the unique identifier on the following line.) This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bird Islet (00S073E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bushy Islet (00S073E0014) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Fedu Island (00S073E0008) -

Biology and Conservation of Xantus's Murrelet

SYMPOSIUM BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF XANTUS’S MURRELET Guest editors Harry R. Carter, Spencer G. Sealy, Esther E. Burkett and John F. Piatt Xantus’s Murrelet chicks shortly before nest departure at Lava Bench, Cave #1, Anacapa Island, California, 28 May 2004 (Photo by D.L. Whitworth). Xantus'sCarter et Murrelet al.: Biology Synthliboramphus and conservation H ypoleucusof Xantus’s Symposium Murrelet 81 BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF XANTUS’S MURRELET: DISCOVERY, TAXONOMY AND DISTRIBUTION HARRY R. CARTER1, SPENCER G. SEALY2, ESTHER E. BURKETT3 & JOHN F. PIATT4 1Carter Biological Consulting, 1015 Hampshire Road, Victoria, British Columbia, V8S 4S8, Canada ([email protected]) 2Department of Zoology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3T 2N2, Canada 3California Department of Fish and Game, Habitat Conservation and Planning Branch, 1416 Ninth Street, Sacramento, California, 95814, USA 4US Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center, 1011 East Tudor Road, Anchorage, Alaska, 99503, USA Received 28 October 2005, accepted 12 January 2006 SUMMARY CARTER, H.R., SEALY, S.G., BURKETT, E.E. & PIATT, J.F. 2005. Biology and conservation of Xantus’s Murrelet: discovery, taxonomy, and distribution. Marine Ornithology 33: 81–87. The biology of Xantus’s Murrelets Synthliboramphus hypoleucus is similar in many respects to better-studied Ancient Murrelets S. antiquus, especially regarding morphology and the species’ precocial mode of post-hatching development. It nests mainly in rock crevices but also under shrubs on islands in southern California, United States, and northwestern Baja California, Mexico (27°N to 34°N). The species was discovered in 1859 by János Xántus. Two subspecies (S. h. hypoleucus and S. h. scrippsi) are recognized that show limited evidence of interbreeding. -

Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, 1973-82

Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea 1973-1982 Concluded at Montego Bay, Jamaica on 10 December 1982 Document:- A/CONF.62/C.2/L.62/Rev.1 Algeria, Dahomey, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tunisia, Upper Volta and Zambia: draft articles on the regime of islands Extract from the Official Records of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Volume III (Documents of the Conference, First and Second Sessions) \ Copyright © United Nations 2009 232 Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea DOCUMENT A/CONF.62/C.2/L.62/Rev. 1 Algeria, Dahomey, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tunisia, Upper Volta and Zambia: draft articles on the regime of islands [Original: French] [27 August 1974] Article I Article 2 1. An island is a vast naturally formed area of land, sur- \: The baselines applicable to adjacent islands, islets, rocks rounded by water, which is above water at high tide. and low-tide elevations, in accordance with article 1, are con- 2. An islet is a smaller naturally formed area of land, sur- sidered as the baselines applicable to the State to which they rounded by water, which is above water at high tide. belong and consequently are used in the measurement of the marine spaces of that State. 3. A rock is a naturally formed rocky elevation of ground, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide. 2. The marine spaces of islands considered non-adjacent, in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 6, shall be delimited on the 4. -

Kinmen Reopens Jiangong Islet to Public

Kinmen reopens Jiangong Islet to public Taipei, Feb. 26 (CNA) Large numbers of tourists have visited Jiangong Islet in Kinmen County since it was recently re-opened to the public, and its rich ecosystem amazes visitors as they walk the stone path in the islet's intertidal zone. Chen Mei-ling (陳美齡), head of the tourism department of the offshore county, said Chinese-English bilingual tourist information is now available to visitors, while new wooden platforms, viewing decks and seashore trails have been built on the islet to provide more comprehensive services to visitors after it was reopened to the public in late January following reconstruction from Dec. 20 last year. The islet, located at the mouth of the Wu River in Jincheng Township and originally named Chu Islet, is 500 meters away from the Kinmen Island and covers 500 square meters. In 1949, it was taken by the Republic of China armed forces, which built stronghold W038 on it in the face of Chinese attacks from the other side of the Taiwan Strait, at a time when the two sides were still at war after the ROC government retreated to Taiwan. It was given the name of Jiangong Islet in 1960 and remained under the control of the ROC military until 1997, when the troops were all withdrawn as part of a military streamlining program. Since then, the islet gradually became dilapidated through lack of care until 2002, when the county government took it over and started repairs in the area with the aim of turning it into a tourist attraction. -

Pancreas Islet Transplantation for Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: a Clinical Evidence Review

Pancreas Islet Transplantation for Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Clinical Evidence Review HEALTH QUALITY ONTARIO SEPTEMBER 2015 Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series; Vol. 15: No. 16, pp. 1–84, September 2015 HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT AT HEALTH QUALITY ONTARIO This report was developed by a multi-disciplinary team from Health Quality Ontario. The lead clinical epidemiologist was Myra Wang, the medical librarian was Caroline Higgins, and the medical editor was Susan Harrison. Others involved in the development and production of this report were Irfan Dhalla, Nancy Sikich, Stefan Palimaka, Andree Mitchell, Farhad Samsami, Christopher Pagano, and Jessica Verhey. We are grateful to Drs. Mark Cattral, Atul Humar, Scott McIntaggart, and Jeffrey Schiff at University Health Network for their clinical expertise and review of the report; and to Ms. Marnie Weber at University Health Network and Ms. Julie Trpkovski at Trillium Gift of Life for the information they provided in helping us contextualize pancreas islet transplantation in Ontario. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series; Vol. 15: No. 16, pp. 1–84, September 2015 2 Suggested Citation This report should be cited as follows: Health Quality Ontario. Pancreas islet transplantation for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a clinical evidence review. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser [Internet]. 2015 Sep;15(16):1–84. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ontario-health-technology- assessment-series/eba-pancreas-islet-transplantation Indexing The Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series is currently indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, Excerpta Medica/Embase, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. Permission Requests All inquiries regarding permission to reproduce any content in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series should be directed to [email protected]. -

Figure 3. the Bioclastic Limestone on the Rocky Islet Seems to Be Lithif Led Under Air and Has Been Dissolved and Leached by Rain 375 14 376 Applications (1)

[Radiocarbon, Vol 25, No. 2, 1983 P 375-379] RADIOCARBON PROFILES OF ROCKY ISLET, XI-SHA ISLANDS: EVIDENCE OF RECENT CRUSTAL MOVEMENTS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA CHEN YEE-CHEIN and JIAO WEN-QIANG Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory, Institute of Geology National Bureau of Seismology, Beijing, China The Xi-Sha Islands comprise 35 coral reefs, cays, and is- lets lying to the northwest of the South China Sea. Since Miocene time, > 1200m of bioherms developed on slowly subsid- ing granite-gneiss bed rock. These sediments provide evi- dence for sea-level changes and crustal movements in the South China Sea. GEOLOGIC SETTING According to an echo sounding survey, the Xi-Sha Islands consist of eight coral reefs scattered regularly around a northeast to northwest trend line. This suggests that the growth of these reefs is tied to the regional tectonic trend and relates to the evolution of the South China Sea. Rocky Islet and Yong-Zing Islet lie on the same reef flat in the Xuan-Dei Islands to the north of the Xi-Sha Islands. The distance between both islets is only ca 1000m, but the geomorphology of both islets are quite different. Rocky Islet consists of cemented bioclastic limestone and its maximum ele- vation is 15m, the highest of the Xi-Sha Islands. Rocky Islet is surrounded with cliffs except in the southeast. An uncon- formity boundary exists in the strata at 8 to lOm elevation. The Yong-Ring Islet is a sandy cay with vegetation, consist- ing of uncemented coral-shell sands 20 to 22m thick. At the center of the islet the elevation is only +3 to +5m. -

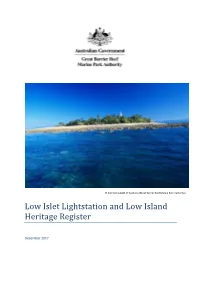

Low Islet Lightstation and Low Island Heritage Register

© Commonwealth of Australia (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority) Low Islet Lightstation and Low Island Heritage Register December 2017 The Low Islet lightstation is listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List for its historic heritage value. Low Island is listed on the Commonwealth Heritage List for its Indigenous heritage value. The property is managed by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, a Commonwealth Government agency. This Register is required by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 s341ZB). It lists the Commonwealth Heritage values that the Marine Park Authority is charged with identifying, conserving, managing, interpreting and celebrating. Commonwealth 105367 Heritage List Place ID Number Current Status Listed place, 28 May 2008 Ownership As the lighthouse is a working aid to navigation it is the property of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA). Otherwise the site is managed by the Marine Park Authority. Location Low Island is in Trinity Bay, about 15 km north east of Port Douglas, and 60 km north of Cairns (16º 23' 02.6” S and 145º 33' 35.58” E) Immediately to its west is Woody Island. Together these islands are known as the Low Isles and their relationship to the mainland can be seen in the Google Map below. On the Google Earth view on the next page, the red arrow is pointing to the light house tower. Google Maps map data © 2018 GBRMPA, Google Australia Commonwealth 105367 Heritage List Place ID Number © Google Description The Low Islets lighthouse was the fifth to be built in northern Queensland using the iron-clad timber-framed method first used at Lady Elliott Island in 1873. -

Download Itinerary

NEMO II: SOUTH ITINERARY - 8 DAYS DAY 1 PM SANTA FE ISLAND SUNDAY Santa Fe island has a beautiful and calm bay and a white sand AM beach, which is home to a large colony of sea lions. A trail will take us to the inner part of the island where we will observe BALTRA the endemic land iguana (present only on this island) lounging around the giant prickly pear cacti. The visit ends Upon your arrival at Baltra airport, your guide will be waiting with some snorkeling in the bay to observe the imposing to welcome you and to help you board the transportation for marine life present in the island´s waters. a short transfer to the dock of Baltra PM DAY 3 BACHAS TUESDAY The name Bachas comes from the local pronunciation of 'barges,' two of which were left by the American army on these shores after World War II. This visitor site has a AM delightful, long beach perfect for swimming or for taking a stroll to observe the wildlife. SAN CRISTOBAL – WITCH HILL – LEON DORMIDO Behind the beach, there is a saltwater lagoon where is usual Located on the northern coast of San Cristobal Island, Witch to find great blue herons and small waders such as Hill is an eroded tuff cone surrounded by a beautiful white sanderlings. The beach is a nesting area for green sea turtles, powdery sand beach with an abundance of animals. Wildlife which leave tracks in the sand after burying their eggs, includes sea turtles, rays, pelicans, sea lions and various types especially from November to February. -

Volume 40, Number 2 Fall 2013

PACIFIC SEABIRDS A Publication of the Pacific Seabird Group Volume 40, Number 2 Fall 2013 PACIFIC SEABIRD GROUP Dedicated to the Study and Conservation of Pacific Seabirds and Their Environment The Pacific Seabird Group (PSG) was formed in 1972 due to the need for better communication among Pacific seabird researchers. PSG provides a forum for the research activities of its members, promotes the conservation of seabirds, and informs members and the public of issues relating to Pacific Ocean seabirds and their environment. PSG members include research scientists, conservation professionals, and members of the public from all parts of the Pacific Ocean. The group also welcomes seabird professionals and enthusiasts in other parts of the world. PSG holds annual meetings at which scientific papers and symposia are presented; abstracts for meetings are published on our web site. The group is active in promoting conservation of seabirds, including seabird/fisheries interactions, monitoring of seabird populations, seabird restoration following oil spills, establishment of seabird sanctuaries, and endangered species. Policy statements are issued on conservation issues of critical importance. PSG’s journals are Pacific Seabirds (formerly the PSG Bulletin) and Marine Ornithology. Other publications include symposium volumes and technical reports; these are listed near the back of this issue. PSG is a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Ornithological Council, and the American Bird Conservancy. Annual dues for membership are $30 (individual and family); $24 (student, undergraduate and graduate); and $900 (Life Membership, payable in five $180 installments). Dues are payable to the Treasurer; see the PSG web site, or the Membership Order Form next to inside back cover. -

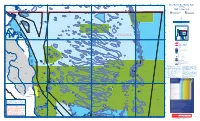

Map1-Editionv-Cape-York.Pdf

142°35'E 142°40'E 142°45'E 142°50'E 142°55'E 143°00'E 143°05'E 143°10'E 143°15'E 143°20'E 143°25'E 143°30'E 143°35'E 143°40'E 143°45'E 143°50'E 143°55'E 144°00'E 144°05'E 144°10'E 144°15'E L Great Barrier Reef Marine Parks Lacey Island Jardine Rock Nicklin Islet Forbes Head Zoning Mt Adolphus (Mori) Island Morilug Islet A do Kai-Damun Reef lph us Johnson Islet S S ' ' 0 0 MAP 1 - Cape York 4 Akone 4 ° Quetta Rock ° 0 L Islet 0 1 C 1 York Island L Mid Rock ha nn 10-807 # # # # # # # Eborac Island (NP) e # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # l # 10°41.207'S Cape York Meggi-Damun Reef 10-348 10-387 L 10-315 10-381 # Sana Rock North Brother North Ledge 10-350 Sextant Rock 10-349 E L# 10-326 10-322 ' 10-313 L 10-325 2 # Tree Island 10-316 10-382 3 Ida Island Middle South Ledge 0 . 10-384 10-314 Bush Islet 10-317 Brother 10-327 5 5 a 10-321 10-323 ° # Albany Rock L L 3 Little Ida Island 4 # L 1 10-386 10-802# Mai Islet 10-320 # L 9 2 Tetley 10-805 10-385 4 t b Pitt Rock 10-319 South - n # 0 0 i d Island 10-351 1 3 o # 10-389 4 P Brother MNP-10-1001 - g # 10-352 S 0 10-324 10-392 S ' r 10-390 ' 1 # 10-443 u Albany Island 5 c 5 b 4 4 a 10-318 ° Fly Point ° n # 10-393 0 10-353 0 s # 10-354 1 O L Ulfa Rock10-328 Triangle Reef 1 10-434 10-355 10-391 # 10-397 Ariel Bank10-329 10-394 ´ 10-356 10-396 Scale 1 : 250 000 L 10-299 10-398 E 10-330 ' # # # 5 10-804 Harrington Shoal # Ch 0 10-399 andogoo Po # 0 5 10 15 20 km in 10-331 9 10-395 t . -

FR4 - Photography & Nature Cruise

FR4 - Photography & Nature Cruise 7 Days / 7 Nights AVAILABLE ONLY FOR CHARTERS TRIPS Night 1: Punta Arenas Arrival to Punta Arenas. Evening meeting at the hotel and welcome dinner. Day 1 Punta Arenas – Barbara Channel Departing from your Hotels at 8 am, we’ll drive out to Punta Carrera (area of Fort Bulnes), from where we’ll board and weigh anchor at 9 pm. Setting off on our adventure, we’ll sail across the Straits of Magellan towards Isla Carlos III in the Francisco Coloane Marine Park (260 sq miles). Day 2 Helado Glacier – Rupert Islet –Carlos III Island In the early morning we’ll navigate through Barbara channels towards the Helado Glacier. We began the navigation to Carlos III Island, enjoying whales watching on route. By Rupert Islet surroundings’ we can see sea wolfs, penguins, skuas, petrels and albatrosses. During the night we sail through the Magellan Strait towards the De Agostini Sound. Day 3 Carlos III – De Agostini Sound –Anguila Glacier In the night, we enter the Magdalena Channel and the Kyats Fjord, travelling towards the De Agostini Sound, dawning in the Aguila Glacier.In the morning we’ll visit Aguila Glacier and those who wants can do kayaking in Bahía Angelito. On midday we departure on direction of the Serrano glacier, where we spent the night. Day 4 Serrano Glacier – Gabriel Channel – Almirantazgo Sound In the morning we’ll visit Vergara Glacier. On midday we departure on direction of the Gabriel Channell, a narrow crossing of extraordinary beauty that leads us into Almirantazgo Sound. From here we’ll continue our journey towards Azopardo Bay to visit a colony of black-browed albatrosses.