Open PDF 380KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Ripley a Rock and Roll Legend in Our Own Backyard Who Has Worked with Some of the Greats

Steve Ripley A rock and roll legend in our own backyard who has worked with some of the greats. Chapter 01 – 1:16 Introduction Announcer: Steve Ripley grew up in Oklahoma, graduating from Glencoe High School and Oklahoma State University. He went on to become a recording artist, record producer, song writer, studio engineer, guitarist, and inventor. Steve worked with Bob Dylan playing guitar on The Shot of Love album and on The Shot of Love tour. Dylan listed Ripley as one of the good guitarist he had played with. Red Dirt was first used by Steve Ripley’s band Moses when the group chose the label name Red Dirt Records. Steve founded Ripley Guitars in Burbank, California, creating guitars for musicians like Jimmy Buffet, J. J. Cale, and Eddie Van Halen. In 1987, Steve moved to Tulsa to buy Leon Russell’s recording facility, The Church Studio. Steve formed the country band The Tractors and was the cowriter of the country hit “Baby Like to Rock It.” Under his own record label Boy Rocking Records, Steve produced such artists as The Tractors, Leon Russell, and the Red Dirt Rangers. Steve Ripley was sixty-nine when he died January 3, 2019. But you can listen to Steve talk about his family story, his introduction to music, his relationship with Bob Dylan, dining with the Beatles, and his friendship with Leon Russell. The last five chapters he wanted you to hear only after his death. Listen now, on VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 3:47 Land Run with Fred John Erling: Today’s date is December 12, 2017. -

Steve Ripley a Rock and Roll Legend in Our Own Backyard Who Has Worked with Some of the Greats

Steve Ripley A rock and roll legend in our own backyard who has worked with some of the greats. Chapter 01 – 1:10 Introduction Announcer: Steve Ripley grew up in Oklahoma, graduating from Glencoe High School and Oklahoma State University. He went on to become a recording artist, record producer, songwriter, studio engineer, guitarist, and inventor. Steve worked with Bob Dylan, playing guitar on the Shot of Love album and on the Shot of Love tour. Dylan listed Ripley as one of his favorite guitarists. The term Red Dirt was first used by Ripley’s band Moses when the group chose the label name Red Dirt Records. Steve founded Ripley Guitars in Burbank, California, creating guitars for musicians like Ry Cooder, J.J. Cale, and Eddie Van Halen. In 1987, Steve moved to Tulsa to buy Leon Russell’s recording studio called The Church Studio. He formed the country band The Tractors and was the co-writer of the country hit “Baby Likes to Rock It.” The first Tractors album sold over two million copies. Steve Ripley was inducted into the Oklahoma Music Awards Red Dirt Hall of Fame, along with Bob Childers and Tom Skinner. Ripley currently is Music Archivist and Curator of the Leon Russell collection for OKPOP. What you are about to hear is a segment from Steve Ripley’s yet-to-be-posted oral history interview, but we wanted you to hear these chapters as he talks about his relationship with Bob Dylan, dining with the Beatles, and his friendship with Leon Russell. Chapter 02 – 10:45 Concept of The Tractors John Erling: Today’s date, April 17, 2018. -

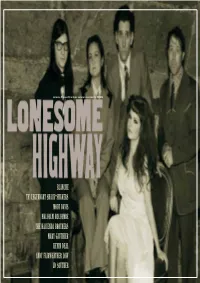

Lonesomehighway Issue4.Pdf

In the fair city of Detroit, nestled among the garage- rock nooks and country crannies, lurks the music of Blanche. Husband and wife Dan and Tracee Miller trade intense and haunting vocals over an uneasy sea of pedal steel, banjo, raw guitar sounds, and sparse, driving drumming. The moods created in the songs seem to define Blanche. Some songs are sad and pretty, while others have a powerful, spooky feel. The melodies trick you into singing along with tales of superstitions, garbage picking, fading trust, and feelings of lost hope. The sound combines the intense desperation of the Gun Club, the sincere sadness of the Carter Family, and the creepy playfulness of Lee Hazlewood Intro taken from the biography on the Blanche website which is well worth a visit and a wonderful design. www.blanchemusic.com INTERVIEW BY STEVE RAPID | PHOTOGRAPHY BY RONNIE NORTON Tell us what the secret of Little Amber Bottles is? Feeny on the pedal steel and his singing. That’s what is most important that overall sound, everyone bringing Well Tracee wrote that song so that’s more for her. I think you can find the answers to little amber bottles in dif- what they have to it. ferent ways, because they can be medication, something that helps you, or you can look to little amber bottles for the wrong reasons. It’s whichever way you use them. I think people rely on medication too much. But you have done some solo shows? Well every once in awhile I do it. I think I’ve done three. -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

80S Music List

80s Music List # .38 Special - Caught Up In You .38 Special - Hold On Loosely .38 Special - Second Chance -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A a-ha - Take On Me A Flock Of Seagulls - I Ran (So Far Away) A Flock Of Seagulls - Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Taste Of Honey - Sukiyaki ABBA - The Winner Takes It All ABC - Be Near Me ABC - The Look Of Love ABC - Poison Arrow ABC - When Smokey Sings AC/DC - Back In Black AC/DC - Hells Bells AC/DC - You Shook Me All Night Long Adam Ant - Goody Two Shoes Aerosmith - Angel Aerosmith - Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Aerosmith - Love In An Elevator Aerosmith - Rag Doll After The Fire - Der Kommissar (English version) Air Supply - All Out Of Love Air Supply - Even The Nights Are Better Air Supply - Every Woman In The World Air Supply - Here I Am (Just When I Thought I Was Over You) Air Supply - Lost In Love Air Supply - Making Love Out Of Nothing At All Air Supply - Sweet Dreams Air Supply - The One That You Love Al B. Sure! - Nite And Day Alabama - Feels So Right Alabama - Love In The First Degree Aldo Nova - Fantasy The Alan Parsons Project - Eye In The Sky The Alan Parsons Project - Games People Play The Alan Parsons Project - Time Ambrosia - Biggest Part Of Me America - You Can Do Magic Animotion - Obsession Anita Baker - Giving You the Best That I Got Anita Baker - Sweet Love Ann Wilson and Robin Zander - Surrender To Me Annie Lennox & Al Green - Put A Little Love In Your Heart Aretha Franklin - Freeway Of Love Aretha Franklin - Pink Cadillac Aretha -

The Life and Songwriting of Vic Chesnutt

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 The Life And Songwriting Of Vic Chesnutt John Hermann University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hermann, John, "The Life And Songwriting Of Vic Chesnutt" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 885. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/885 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LIFE AND SONGWRITING OF VIC CHESNUTT A Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by John Hermann May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by John Hermann All rights reserved ABSTRACT This thesis is an exploration of the life and music of Vic Chesnutt, and it accompanies a documentary film. Both components feature interview excerpts from over 30 hours of film footage with Chesnutt, as interspersed with archival documents of his life, along with dozens of interviews with his family, friends, peers, music writers, and bandmates. Chesnutt’s story can only be properly told through the lens of southern culture. He was not just a charter member of an international group, but a southern songwriter whose rural Georgia upbringing was paramount to his work. He has often been compared in music journals to the southern gothic schoolmates of William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Carson McCullers, placing his songs in the context of southern writers. -

ASCAP/BMI Comment

Stuart Rosen Senior Vice President General Counsel November 20, 2015 Chief, Litigation III Section Antitrust Division U.S. Department of Justice 450 5th Street NW, Suite 4000 Washington, DC 20001 Re: Justice Department Review of the BMI and ASCAP Consent Decrees To the Chief of the Litigation III Section: BMI recently alerted its community of affiliated songwriters, composers and publishers to the profound impact 100% licensing would have on their careers, both creatively and financially, if it were to be mandated by the U.S. Department of Justice. In a call to action, BMI provided a letter, one for songwriters and one for publishers, to which their signatures could be added. The response was overwhelming. BMI received nearly 13,000 signatures from writers, composers and publishers of all genres of music, at all levels in their careers. Some of the industry's most well- known songwriters added their names, including Stephen Stills, Cynthia Weil, Steve Cropper, Ester Dean, Dean Pitchford, Congressman John Hall, Trini Lopez, John Cafferty, Gunnar Nelson, Lori McKenna, Shannon Rubicam and Don Brewer, among many others. Enclosed you will find the letters, with signatures attached. On behalf of BMI, I strongly urge you to consider the voices of thousands of songwriters and copyright owners reflected here before making a decision that will adversely affect both the creators, and the ongoing creation of, one ofAmerica's most important cultural and economic resources. Vert truly yours, Stuart Rosen 7 World Trade Center, 250 Greenwich Street, New York, NY 10007-0030 (212) 220-3153 Fax: (212) 220-4482 E-Mail: [email protected] ® A Registered Trademark of Broadcast Music, Inc.