2004 Annual Survey: Recent Developments in Sports Law Jenna Merten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared for Success

2015-2016 Gratitude Report Prepared for Success Thanks to the support of our donors, our bright kids will continue to have bright futures! Our Mission Chesapeake Bay Academy educates students through academic programs individualized to address their learning differences, empowering them with the skills and confidence necessary for success in higher education, careers and life. Board of Trustees Stanley F. Baldwin, Esq. Chair Donald L. Glenum, III Vice Chair & Treasurer William P. Brittain, Ph.D. Secretary Patrick D. Thrasher, M.D. Immediate Past Chair Jennifer Adams Parent Association President Judy Jankowski, Ed.D. Head of School Edward J. Amorosso J.D. Ball, Ph.D. Keith H. Bangel, Esq. Elizabeth Patterson Bertrand Linda D. Bowers William B. Brock Chuck Brooks, Ph.D. Aaron J. Cooper Peter M. Dozier, M.D. L. Matthew Frank, M.D. Thomas L. Hasty, III William W. King Dave Levin, M.D. Alan B. Rashkind, Esq. Teri M. Rigell Bruce L. Rubin, Ph.D. Robert Sharak Eleanor Stanton Richard B. Thurmond John A. Trinder Emeritus Dennis R. Deans MaryAnne Dukas Dee H. Roberts Creating Life-long Learners Chesapeake Bay Academy’s goal is to create life-long learners who are well prepared for their future. CBA students are empowered learners ready to make a positive impact on the world. Serving as a member of the Board of Trustees, and now as Board Chair, I have learned how very special Chesapeake Bay Academy truly is and what a vital resource the school is to the Hampton Roads Community. Over the past year several members of the Board of Trustees, along with the Head of School, have focused on developing CBA’s long-range strategic plan. -

Hockey Apparel Free Shipping

Hockey apparel free shipping Discounts average $11 off with a NHL Shop promo code or coupon. 34 NHL Shop coupons now on RetailMeNot. NHL Draft Hats Available 2, - Dec 31, Discounts average $10 off with a Gongshow Lifestyle Hockey Apparel promo code or coupon. 37 Gongshow Lifestyle Hockey Apparel coupons now on May 4, - Dec 31, No Sales Tax. Except CA. Free Same Day Shipping. On all orders over $ & before 4PM EST. Day Returns. Now easier than ever! Contact · Login. Discount Hockey carries the best selection of hockey equipment, ice skates, sticks, helmets, gloves, accessories, custom jerseys, goalie equipment, and more!Clearance · Skates · Sticks · Helmets. 50 best Gongshow Lifestyle Hockey Apparel coupons and promo codes. Save big on apparel and accessories. Today's top deal: $30 off. 8 verified NHL coupons and promo codes as of Oct Shop NHL Kid's Apparel The Hot Off The Ice sales section has discount merchandise of all types. Shop clearance hockey apparel & gear at DICK'S Sporting Goods today. Check out customer reviews and learn more about these great products. 29 Promo Codes for | Today's best offer is: Free Shipping on orders San Jose Sharks Western Conference Champions Fan Gear starting at $ women and kids. Get the latest NHL clothing and exclusive gear at hockey fan's favorite shop. Adidas Authentic NHL Jerseys; 9. NHL Coupons & Promos. Save up to 60% on select merchandise from ! Buy discounted shirts, hats, sweatshirts, and more apparel from the official store of the NHL. with coupon code ITP. coupons and deals also available for October Shop vintage NHL apparel with prices starting at $ NHL Shop Coupons, Promo Codes, and Discounts. -

South Carolina Stingrays Hockey 3300 W

SOUTH CAROLINA STINGRAYS HOCKEY 3300 W. Montague Ave. Suite A-200 - North Charleston, SC 29418 Jared Shafran, Director of Media Relations and Broadcasting | [email protected] | (843) 744-2248 ext. 1203 2019-20 SCHEDULE October (5-1) Sat • 12th @ Orlando Solar Bears W, 4-2 South Carolina Stingrays vs. Greenville Swamp Rabbits Fri • 18th @ Atlanta Gladiators W, 5-3 Sat • 19th vs. Orlando Solar Bears W, 4-2 Friday, November 8 • Greenville, SC Wed • 23rd @ Norfolk Admirals L, 2-5 Fri • 25th @ Norfolk Admirals W, 4-3 OT 2019-20 Team Comparison (ECHL Rank) Sat • 26th @ Norfolk Admirals W, 3-0 South Carolina Greenville November Sun • 3rd @ Orlando Solar Bears W, 8-2 GF/G 4.29 (5th) 4.30 (3rd) Fri • 8th @ Greenville Swamp Rabbits 7:05 p.m. Sat • 9th @ Greenville Swamp Rabbits 7:05 p.m. Fri • 15th vs. Indy Fuel 7:05 p.m. GA/G 2.43 (2nd) 4.20 (23rd) Sat • 16th vs. Norfolk Admirals 6:05 p.m. Sun • 17th vs. Norfolk Admirals 3:05 p.m. PP% 14.7% (18th) 17.1% (15th) Tue • 19th vs. Greenville Swamp Rabbits 7:05 p.m. Fri • 22th @ Florida Everblades 7:30 p.m. PK% 77.8% (20th) 81.0% (15th) Sat • 23rd @ Florida Everblades 7:00 p.m. Sat • 30th @ Orlando Solar Bears 7:00 p.m. 6-1-0-0 5-5-0-0 December Mon • 2nd @ Orlando Solar Bears 7:00 p.m. Stingrays Look To Stay Hot During Weekend Series In Greenville Wed • 4th @ Atlanta Gladiators 7:05 p.m. Fri • 6th @ Florida Everblades 7:00 p.m. -

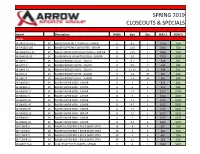

Spring 2019 Closeouts & Specials

SPRING 2019 CLOSEOUTS & SPECIALS Item # Description Width Size Qty WAS $ NOW $ SKATES SK-BAS170J-45EE SK BAUER SUPREME 170 SKATES - JUNIOR EE 4.5 1 $150 $50 SK-BA160S-105 SK BAUER SUPREME S160 SKATES - SENIOR D 10.5 2 $162 $50 SK-BAX600S-115 SK BAUER VAPOR X600 SKATES (2015) - SENIOR D 11.5 1 $242 $50 SK-BAN1NS-10 SK BAUER NEXUS 1N SKATES (2016) - SENIOR D 10 1 $720 $250 SK-BAPY-7 SK BAUER PRODIGY SKATE - YOUTH R 6-7 5 $48 $35 SK-BAPY-9 SK BAUER PRODIGY SKATE - YOUTH R 8-9 9 $48 $35 SK-BAPY-13 SK BAUER PRODIGY SKATE - YOUTH R 12-13 11 $48 $35 SK-BAPJ-2 SK BAUER PRODIGY SKATE - JUNIOR R 1-2 29 $60 $40 SK-BAPJ-4 SK BAUER PRODIGY SKATE - JUNIOR R 3-4 34 $60 $40 SK-BX400J-2 SK BAUER VAPOR X400 - JUNIOR R 2 2 $73 $49 SK-BX400J-4 SK BAUER VAPOR X400 - JUNIOR R 4 2 $73 $49 SK-BX600J-15 SK BAUER VAPOR X600 - JUNIOR D 1.5 1 $152 $105 SK-BX600J-3 SK BAUER VAPOR X600 - JUNIOR D 3 5 $152 $105 SK-BX600J-35 SK BAUER VAPOR X600 - JUNIOR D 3.5 2 $152 $105 SK-BX600J-45 SK BAUER VAPOR X600 - JUNIOR D 4.5 1 $152 $105 SK-BX600J-55 SK BAUER VAPOR X600 - JUNIOR D 5.5 2 $152 $105 SK-BX600S-12 SK BAUER VAPOR X600 - SENIOR D 12 1 $237 $150 SK-BX800J-2 SK BAUER VAPOR X800 - JUNIOR D 2 1 $265 $175 SK-BX800J-25 SK BAUER VAPOR X800 - JUNIOR D 2.5 3 $265 $175 SB-TLS4ER-4 SB BAUER LIGHTSPEED 4 EDGE SKATE STEEL JR 4 4 $62 $50 SB-TLS4ER-6 SB BAUER LIGHTSPEED 4 EDGE SKATE STEEL SR 6 6 $62 $50 SB-TLS4ER-7 SB BAUER LIGHTSPEED 4 EDGE SKATE STEEL SR 7 6 $62 $50 SB-TLS4ER-11 SB BAUER LIGHTSPEED 4 EDGE SKATE STEEL SR 11 6 $62 $50 SK-CMJFT1S-6 SK CCM JETSPEED FT1 SKATES - SENIOR -

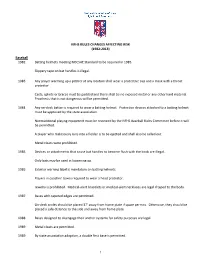

Nfhs Rules Changes Affecting Risk (1982-2013)

NFHS RULES CHANGES AFFECTING RISK (1982-2013) Baseball 1982 Batting helmets meeting NOCSAE Standard to be required in 1985. Slippery tape on bat handles is illegal. 1983 Any player warming up a pitcher at any location shall wear a protective cup and a mask with a throat protector Casts, splints or braces must be padded and there shall be no exposed metal or any other hard material. Prosthesis that is not dangerous will be permitted. 1984 Any on-deck batter is required to wear a batting helmet. Protective devices attached to a batting helmet must be approved by the state association. Nontraditional playing equipment must be reviewed by the NFHS Baseball Rules Committee before it will be permitted. A player who maliciously runs into a fielder is to be ejected and shall also be called out. Metal cleats were prohibited. 1985 Devices or attachments that cause bat handles to become flush with the knob are illegal. Only bats may be used in loosening up. 1986 Exterior warning label is mandatory on batting helmets. Players in coaches’ boxes required to wear a head protector. Jewelry is prohibited. Medical-alert bracelets or medical-alert necklaces are legal if taped to the body. 1987 Bases with tapered edges are permitted. On-deck circles should be placed 37’ away from home plate if space permits. Otherwise, they should be placed a safe distance to the side and away from home plate. 1988 Bases designed to disengage their anchor systems for safety purposes are legal. 1989 Metal cleats are permitted. 1989 By state association adoption, a double first base is permitted. -

Other Hockey Leagues

OTHER HOCKEY LEAGUES {Appendix 4.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 16} Research completed as of August 7, 2015 NATIONAL WOMEN’S HOCKEY LEAGUE League Update: The league’s inaugural season will begin in October 2015 with four teams: Boston Pride, Buffalo Beauts, Connecticut Whale, and New York Riveters. All the teams are owned and paid for through the NWHL Foundation, which is a non-profit organization. The foundation is depending on donations to fulfill its goal of being able to pay the players, and provide the education and training opportunities to youths to increase female participation in hockey throughout the country. Team: Boston Pride Year Established: 2015 Team Website Twitter: @TheBostonPride Arena: Harvard Bright-Landry Center Date Built: 1979 Facility Cost ($/Mil): N/A Percentage of Arena Publicly Financed: N/A Facility Financing: N/A Facility Website Twitter: N/A UPDATE: The Boston Pride open the season on October 11, 2015. NAMING RIGHTS: Named after Alexander H. Bright, a former Harvard hockey player, and rechristened in honor of the longtime support from alumnus C. Kevin Landry. © Copyright 2015, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Buffalo Beauts Year Established: 2015 Team Website Twitter: @BuffaloBeauts Arena: The HarborCenter Date Built: 2014 Facility Cost ($/Mil): $172.2 Percentage of Arena Publicly Financed: 0%, however, the Harbor Center is publicly subsidized, receiving $57 million in local and state tax breaks. Facility Financing: N/A Facility Website Twitter: @HarborCtr UPDATE: The Harbor Center is a new arena that opened in November 2014. Facility construction will be completed in 2015. -

Parks & Recreation

YORKTOWN PARKS & RECREATION Creating Community Through People, Parks And Programs Spring/Summer 2020 General Registration Begins March 24th! | Day Camp Registration Details Page 21 TABLE OF CONTENTS Staff Lists/Contact Information .......................................1 Golf & Tennis .............................................................15-16 Yorktown Supervisor Letter .............................................1 Youth Sports & Specialty Camps .............................16-20 Registration/Refund & Important Information ............2 Day Camps .................................................................21-23 Special Events .....................................................................3 Aquatics Programs ..........................................................23 Town Parades .....................................................................3 Pool/Beach Information & Hours .................................24 Special Programs & Vacation Camps .............................4 Pool Pass Memberships ............................................24-25 Pre-School Programs - Youth Programs ....................4-6 Cooperating Agencies .....................................................26 Youth - Teen Programs ...............................................7-10 Program Registration Form ...........................................26 Adult Sports Information & Activities .....................9-13 Camper Registration & Medical Form ...................27-28 Senior Citizen Programs ..........................................13-15 -

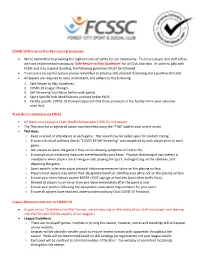

COVID-19 RETURN to PLAY PROTOCOLS & GUIDELINES • We

COVID-19 RETURN TO PLAY PROTOCOLS & GUIDELINES We’re committed to providing the highest levels of safety for our community. To ensure player and staff safety, we have implemented mandatory 'Safe Return to Play Guidelines' for all Club Activities. In order to play with FCSSC and stay in good standing, the following guidelines MUST be followed. To ensure a successful season, please remember to practice safe physical distancing and a positive attitude! All players are required to read, understand, and adhere to the following: 1. Safe Return to Play Guidelines 2. COVID-19 League Changes 3. Self Screening Tool (done before each game). 4. Sport-Specific Rule Modifications outlined below PLUS, 5. Facility specific COVID-19 Protocols (you can find these protocols in the facility link in your schedule once live). TEAM HEALTH AMBASSADOR (THA) All teams must assign a Team Health Ambassador (THA) for the season. The THA must be a registered player and identified using the “THA” label in your online roster. THA Role: o Keep a record of attendance at each game. This record may be called upon for contact tracing. o Ensure individual wellness checks “COVID-19 Self Screening” are completed by each player prior to each game. o Ask players to leave the game if they arrive showing symptoms of cold or flu. o Ensure physical distancing measures are enforced by your team. Physical distancing of two meters is mandatory when players are arriving on-site, playing the sport, resting/sitting on the sidelines, and departing the game. o Sport-specific rules may adjust physical distancing measures taken on the playing surface. -

Ccm-Team-Catalog-2020

CCM HOCKEY 2020 TEAM PRODUCT GUIDE WEBSITE CCMHOCKEY.COM TO START YOUR B2B ONLINE SHOPPING, GO TO WWW.GO2CCMHOCKEY.COM AND CLICK ON “REQUEST LOGIN”. FIND US ON SOCIAL MEDIA WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/CCMHOCKEY @CCMHOCKEY CCMHOCKEY CCM_OFFICIAL HEAD OFFICE LOCATIONS NORTH CCM HOCKEY © 2019 SPORT MASKA INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. CCM®, SUPERTACKS®, RIBCOR® AND THE CCM STYLIZED LOGO REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF SPORT MASKA INC. AMERICA 3400, RAYMOND-LASNIER, MONTRÉAL, QUÉBEC H4R 3L3 NHL AND THE NHL SHIELD ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE. ALL NHL LOGOS AND MARKS AND TEAM LOGOS AND MARKS DEPICTED HEREIN ARE THE PROPERTY OF THE NHL AND THE RESPECTIVE TEAMS AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT OF NHL ENTERPRISES, L.P. © NHL CANADA 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. © PHOTOS: GETTY IMAGES. TEL.: (800) 636-5895 FAX: (800) 636-5751 † : THIS CATALOG MAY REFER TO THE FOLLOWING TRADEMARKS WHICH ARE OWNED BY THE COMPANIES WHOSE NAMES APPEAR AFTER THE TRADEMARK: AHL - - AMERICAN HOCKEY LEAGUE; CLARINO - - HURARAY CO. LTD.; CHL - - CANADIAN HOCKEY LEAGUE; LYCRA, SPANDEX AND SURLYN - - E.I. DUPONT DE NEMOURS AND COMPANY; ECHL - - ECHL EUROPE CCM HOCKEY AB INC.; PLAYDRY - - REEBOK INTERNATIONAL LTD; TACTEL - - INVISTA; VELCRO - - VELCRO INDUSTRIES B.V.; THINSULATE IS A TRADEMARK OF 3M, USED UNDER LICENSE IN GÅRDSVÄGEN 13 CANADA; D3O® - - DESIGN BLUE LTD.; JETSPEED - - TAYLORMADE GOLF COMPANY INC.; SIGMATEX - - SIGMATEX (UK) LIMITED; POLYGIENE - - POLYGIENE AB SE 16970 SOLNA WARNING : HOCKEY IS A DANGEROUS COLLISION SPORT. WE RECOMMEND THAT PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT AND A CERTIFIED HELMET BE WORN AT ALL TIMES. SWEDEN TEL.: + 46 (0) 8 522 352 00 SPORT MASKA INC. -

Annual Report ---- 2014-2015

ANNUAL REPORT ---- 2014-2015 ---- 3349221_Report_v7.indd49221_Report_v7.indd 1 22/11/16/11/16 111:201:20 AAMM President Steven F. Waranch, Psy. D TO OUR FRIENDS Vice President Rev. Mark Wilkinson & SUPPORTERS Secretary On behalf of our Board, staff and the 20,000 youth we serve annually Maxine Singleton, Ed.D through our Shelters, Street Outreach and Mentoring programs, I want Treasurer to thank you for taking a moment to review our past year’s activities. I John Babcock just marked my third year as Executive Director of Seton Youth Shelters, Immediate and it is an honor to serve in this capacity. 2015 also marked the start Past President of Seton Youth Shelters 30th year of serving runaway, homeless and Michael A. Inman, Esq. at-risk youth in our region and beyond. And, in those 30 years, we have changed the lives of more than 250,000 youth for the better. Daniel Barton, D.D.S. Diana Breuss This past year, we provided thousands of shelter nights, meals and Chuck Gray support services, and mentoring partnerships to our region’s youth. Becky Rankin We also assisted four underage victims of human sex trafficking from Kelly Rowe Linda Spindel across the country through our shelter program. But, I'm going to stop Gerald M. Travis myself there with numbers and statistics, because when it comes to James White your support of Seton, it's not those numbers that affect your decision Ros Willis to support our organization. Like me, it’s probably an experience you Brian Winfield have had with one person—one person whose story touched you and Mandy Yoder made you realize how important it is to support our mission. -

Safety Media Kit 2004

USA Hockey Safety Media Kit Introduction As the National Governing Body for the violent in nature, sport of ice hockey, USA Hockey is this is a committed to promoting and fostering safety disproportionate amongst its athletes, coaches and supporters. representation, and the vast majority of As such, it is the organization’s role to hockey injuries are unintentional. educate its membership, through brochures, instructional videos and training seminars, USA Hockey Regulation on the meaning of fair play and respect for 1. The Safety and Protective Equipment the individual. USA Hockey values the Committee, led by Chairperson Dr. Alan safety of all its participants, and aspires to Ashare, continually studies the game at make the game safe, fun and rewarding for all age levels for the purpose of its membership. developing means and methods of maintaining and improving player safety. The committee also has the duty to Facts About Safety and USA Hockey recommend rule changes pertaining to 1. USA Hockey and USA Hockey InLine are safety. The committee must consist of at not insurance companies and do not sell least three members of the Board of insurance. However, the organization Directors and/or District Registrars, does provide insurance coverage for all appointed by the USA Hockey President, member players, coaches and referees who shall designate the Chairperson of participating in sanctioned activities. the Committee. 2. More than 65% of USA Hockey’s 500,000 2. The Playing Rules Committee has a players skate in a no-check hockey similar role to that of the Safety and league. This includes all girls’/women’s Protective Equipment Committee. -

College of Arts and Letters Maj

COLLEGE OF ARTS AND LETTERS MAJ. YEAR TITLE BUSINESS CITY STATE Art 2007 Clerk USCG Alexandria VA Communication 2014 Film Specialist University of Texas at Austin Austin TX Communication 2014 Graduate Student Syracuse University Winchester VA Communication 2014 Marketing Coordinater Monarch Mortgage Virginia Beach VA Communication 2014 Production Instructor School of Creative and Performing Arts Lorton VA Communication 2013 Graphics & Promotions Coordinator Ocean Breeze Waterpark Virginia Beach VA Communication 2013 Sales Associate Tumi Washington DC Communication 2013 Recriter Aerotek Norfolk VA Communication 2013 Operations Administration The Franklin Johnston Group Chesapeake VA Communication 2013 Social Media Specialist Dominion Enterprises Newport News VA Communication 2013 Realtor Rose & Womble Realty Chesapeake VA Communication 2013 Legal Assistant Harry R. Purkey, Jr. P.C. Virginia Beach VA Communication 2012 Public Relations Asst Account Executive BCF Virginia Beach VA Communication 2012 Event Designer Amphora Catering Annandale VA Communication 2012 Assistant Manager Mark's Bar-B-Que Zone LLC Marion VA Communication 2012 Assignment Editor WTVR-TV Richmond VA Communication 2012 Team Leader Neebo Bookstores at John Tyler Community College Virginia Beach VA Communication 2012 Marketing and Communiactions Coordinator The Pacific Club Wahiawa HI Communication 2012 Leadership Consultant Omicron Delta Kappa Lexington VA Communication 2011 Regional Vice President Specialists On Call, Inc. Ocean City MD Communication 2011 Administrative Assistant Eagle Haven Golf Course Virginia Beach VA Communication 2011 Account Manager Bizport Laguna Niguel CA Communication 2011 Human Resources Officer U.S. Army Apo AP Communication 2011 REALTOR Long & Foster Real Estate Inc. Franklin VA Communication 2011 Marketing Communications Specialist Crawford Group Campbell CA Communication 2011 Social Media Specialist Meridian Group Virginia Beach VA Communication 2011 Assoc.