CONGO CINEMA REPORT Evaluation of the Long-Term

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Langue Catégorie Chaine Qualité • Cinéma DE • Allemagne Cinéma

Langue Catégorie Chaine Qualité •●★ Cinéma DE ★●• Allemagne Cinéma Family TV FHD HD Allemagne Cinéma Kinowelt HD Allemagne Cinéma MGM FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY ATLANTIC (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA 1 (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema 24 FHD HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema 24 HD HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA ACTION FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA ACTION (FHD) FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA FAMILY (FHD) HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Cinema HD FHD Allemagne Cinéma SKY CINEMA HITS (FHD) HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY EMOTION HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Hits HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Hits HD HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Krimi HD Allemagne Cinéma Sky Nostalgie HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 1 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 2 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 3 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 4 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 5 HD Allemagne Cinéma SKY SELECT 6 •●★ Culture DE ★●• Allemagne Culture 3SAT HD Allemagne Culture A & E HD Allemagne Culture Animal Planet HD HD Allemagne Culture DISCOVERY HD HD Allemagne Culture Goldstar TV HD Allemagne Culture Nat Geo Wild HD Allemagne Culture Sky Dmax HD HD Allemagne Culture Spiegel Geschichte HD Allemagne Culture SWR Event 1 HD Allemagne Culture SWR Event 3 HD Allemagne Culture Tele 5 HD HD Allemagne Culture WDR Event 4 •●★ Divertissement DE ★●• Allemagne Divertissement13TH STREET FHD Allemagne Divertissement13TH STREET (FHD) HD Allemagne DivertissementA&E HD Allemagne DivertissementAustria 24 TV HD Allemagne DivertissementComedy Central / VIVA AT HD Allemagne DivertissementDMAX -

LES CHAÎNES TV by Dans Votre Offre Box Très Haut Débit Ou Box 4K De SFR

LES CHAÎNES TV BY Dans votre offre box Très Haut Débit ou box 4K de SFR TNT NATIONALE INFORMATION MUSIQUE EN LANGUE FRANÇAISE NOTRE SÉLÉCTION POUR VOUS TÉLÉ-ACHAT SPORT INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE MULTIPLEX SPORT & ÉCONOMIQUE EN VF CINÉMA ADULTE SÉRIES ET DIVERTISSEMENT DÉCOUVERTE & STYLE DE VIE RÉGIONALES ET LOCALES SERVICE JEUNESSE INFORMATION INTERNATIONALE CHAÎNES GÉNÉRALISTES NOUVELLE GÉNÉRATION MONDE 0 Mosaïque 34 SFR Sport 3 73 TV Breizh 1 TF1 35 SFR Sport 4K 74 TV5 Monde 2 France 2 36 SFR Sport 5 89 Canal info 3 France 3 37 BFM Sport 95 BFM TV 4 Canal+ en clair 38 BFM Paris 96 BFM Sport 5 France 5 39 Discovery Channel 97 BFM Business 6 M6 40 Discovery Science 98 BFM Paris 7 Arte 42 Discovery ID 99 CNews 8 C8 43 My Cuisine 100 LCI 9 W9 46 BFM Business 101 Franceinfo: 10 TMC 47 Euronews 102 LCP-AN 11 NT1 48 France 24 103 LCP- AN 24/24 12 NRJ12 49 i24 News 104 Public Senat 24/24 13 LCP-AN 50 13ème RUE 105 La chaîne météo 14 France 4 51 Syfy 110 SFR Sport 1 15 BFM TV 52 E! Entertainment 111 SFR Sport 2 16 CNews 53 Discovery ID 112 SFR Sport 3 17 CStar 55 My Cuisine 113 SFR Sport 4K 18 Gulli 56 MTV 114 SFR Sport 5 19 France Ô 57 MCM 115 beIN SPORTS 1 20 HD1 58 AB 1 116 beIN SPORTS 2 21 La chaîne L’Équipe 59 Série Club 117 beIN SPORTS 3 22 6ter 60 Game One 118 Canal+ Sport 23 Numéro 23 61 Game One +1 119 Equidia Live 24 RMC Découverte 62 Vivolta 120 Equidia Life 25 Chérie 25 63 J-One 121 OM TV 26 LCI 64 BET 122 OL TV 27 Franceinfo: 66 Netflix 123 Girondins TV 31 Altice Studio 70 Paris Première 124 Motorsport TV 32 SFR Sport 1 71 Téva 125 AB Moteurs 33 SFR Sport 2 72 RTL 9 126 Golf Channel 127 La chaîne L’Équipe 190 Luxe TV 264 TRACE TOCA 129 BFM Sport 191 Fashion TV 265 TRACE TROPICAL 130 Trace Sport Stars 192 Men’s Up 266 TRACE GOSPEL 139 Barker SFR Play VOD illim. -

Annexes Budgétaires

RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE 9 COMPTE DE CONCOURS FINANCIERS MISSION MINISTÉRIELLE 1 PROJETS ANNUELS DE PERFORMANCES 0 ANNEXE AU PROJET DE LOI DE FINANCES POUR 2 AVANCES À L'AUDIOVISUEL PUBLIC NOTE EXPLICATIVE La présente annexe au projet de loi de finances est prévue aux 5° et 6° de l’article 51 de la loi organique relative aux lois de finances du 1er août 2001 (LOLF). Conformément aux dispositions de la LOLF, cette annexe, relative à un compte de concours financiers, comporte notamment : – les évaluations de recettes annuelles du compte ; – les crédits annuels (autorisations d’engagement et crédits de paiement) demandés pour chaque programme du compte-mission ; – un projet annuel de performances (PAP) pour chaque programme, qui se décline en : - présentation stratégique du PAP du programme ; - objectifs et indicateurs de performances du programme ; – la justification au premier euro (JPE) des crédits proposés pour chaque action de chacun des programmes. Sauf indication contraire, les montants de crédits figurant dans les tableaux du présent document sont exprimés en euros. L’ensemble des documents budgétaires ainsi qu’un guide de lecture et un lexique sont disponibles sur le Forum de la performance : http://www.performance-publique.budget.gouv.fr TABLE DES MATIÈRES Compte de concours financiers AVANCES À L'AUDIOVISUEL PUBLIC 7 Présentation du compte 8 Présentation de la programmation pluriannuelle 9 Équilibre du compte et évaluation des recettes 10 Récapitulation des crédits 12 Programme 841 FRANCE TÉLÉVISIONS 13 Présentation stratégique du -

|Fr|Hd| France ##### |Fr| Flix

##### |FR|HD| FRANCE ##### |FR| RTS UN HD |FR| CORONA VIRUS INFO |FR| RTS DEUX HD |FR| TF1 HD |FR| CSTAR HD |FR| FRANCE 2 HD |FR| LA CHAINE METEO HD |FR| FRANCE 3 HD |FR| MEZZO FR |FR| FRANCE 4 HD |FR| MUSEUM HD |FR| FRANCE 5 HD |FR| COMEDIE HD |FR| FRANCE 3 NOA HD |FR| COMEDY CENTRAL HD |FR| 6TER HD |FR| VIAGRANDPARIS |FR| M6 HD |FR| CANAL 31 |FR| TF1 SERIES FILMS HD |FR| CANAL 8 HD |FR| TFX HD |FR| CLIQUE TV HD |FR| RTL 9 HD |FR| EQUIPE 21 HD |FR| TEVA HD |FR| IDF 1 |FR| TMC HD |FR| OLYMPIA HD |FR| W9 HD |FR| KTO |FR| ARTE HD |FR| BOOSTER TV HD |FR| NON STOP PEOPLE HD |FR| LEMAN BLEU HD |FR| NOVELAS TV HD |FR| CANAL 9 HD |FR| ONE TV HD |FR| THE SWIZZ HD |FR| ROUGE TV HD |FR| OLTV ##### |FR|HD| CH. CANAL+ ##### |FR| FLIX MOVIES HISTORIQUE HD |FR| CANAL+ HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES DOCUMENTAIRE |FR| CANAL+ SPORT HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ANIMATION HD |FR| CANAL+ PREMIER LEAGUE HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JASON STATHAM |FR| CANAL+ SERIE HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ANGELINA JOLIE |FR| CANAL+ FAMILY HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES TOM CRUISE |FR| CANAL+ DECALE HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES MORGAN FREEMAN |FR| CANAL+ CINEMA HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JACKIE CHAN |FR| CANAL+ FORMULE1 HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES VAN DAMME |FR| CANAL+ MOTOGP HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JOHN TRAVOLTA |FR| CANAL+ TOP14 HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES NICOLAS CAGE ##### |FR|HD| CINEMA ##### |FR| FLIX MOVIES MEL GIBSON |FR| FLIX MOVIES HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ROBERT DE NIRO |FR| FLIX MOVIES ACTION HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES JIM CARREY |FR| FLIX MOVIES DRAMA HD |FR| ACTION HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES ROMANCE HD |FR| OCS MAX HD |FR| FLIX MOVIES COMEDY |FR| OCS CITY HD -

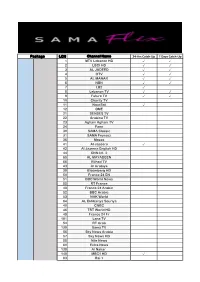

LCN 24-Hrs Catch-Up 7 Days Catch-Up 1 2 3 4 5 6

Package LCN Channel Name 24-Hrs Catch-Up 7 Days Catch-Up 1 MTV Lebanon HD ✓ ✓ 2 LBCI HD ✓ ✓ 3 AL JADEED ✓ ✓ 4 OTV ✓ ✓ 5 AL MANAR ✓ ✓ 6 NBN ✓ ✓ 7 LB2 ✓ 8 Lebanon TV ✓ ✓ 9 Future TV ✓ ✓ 10 Charity TV 11 NourSat ✓ 12 ONE 21 SENSES TV 22 Arabica TV 23 Aghani Aghani TV 24 Fann 30 SAMA Classic 31 SAMA Feyrouz 36 Mezzo 41 Al Jazeera ✓ 42 Al Jazeera English HD 44 CNN Int. 2 65 AL MAYADEEN 66 Etihad TV 43 Al Arabiya 39 Bloomberg HD 50 France 24 EN 51 BBC World News 55 RT France 48 France 24 Arabic 52 BBC Arabic 53 NHK World 64 AL Ekhbariya Souriya 40 CNBC 46 TRT World HD 49 France 24 Fr 181 Lana TV 54 RT Arab 139 Sama TV 56 Sky News Arabia 57 Sky News HD 58 Nile News 60 Extra News 138 Al Nahar 148 MBC1 HD ✓ 83 Rai 1 Basic FULL 85 1TVRUS Europe 86 Armenia TV 87 C1 Armenia 88 ATV 90 EBS TV 93 FOX TV 94 KANAL 7 AVRUPA 95 KANAL D 96 Kentron 103 SHOW HD 104 SHOW MAX 106 STAR TV 107 TFC 111 SYRIA DRAMA 112 SAT-7 ARABIC 89 TRT1 47 DW 125 AL Anwar 126 AL Maaref 127 AL Sirat 128 AL Iman TV 129 Noor Dubai 130 AlAqliya 131 Karbala 132 Dubai tv 133 Sama Dubai 134 CBC 135 Nile Tv 136 Al Nas 137 Al Majd 146 MBC Masr 140 Nile Life 142 Fatafeat HD 143 Bein Gourment HD 145 CBC Sofra 147 MBC Masr 2 151 MBC4 HD ✓ 152 MBC+ Drama HD ✓ 153 MBC Drama HD ✓ 154 AD DRAMA 260 FOX Rewayat ✓ 175 Rotana Cinema 165 Rotana Comedy HD Basic 166 Rotana Drama HD 168 Rotana Classic 177 Nile cinema 178 Nile drama 179 CBC Drama 180 Nile Comedy 201 MBC2 HD ✓ 202 MBC Action HD ✓ 203 MBC MAX HD ✓ 204 MBC P VARIETY ✓ 205 MBC Bollywood HD ✓ 254 BBC First HD FULL Basic 255 FOX Family Movie -

Genre Language English Package

Genre Language English Package News English Channel News Asia News English France 24 English News English CNBC News English BBC World HD News English CNN HD News English HLN News English World Is One News Movies English Star Movies HD Movies English Turner Classic Movies Movies English Film Box HD Movies English Film Box Arthouse Movies English Cinemachi Movies English Fox Family Movies HD Movies English Fox Action Movies HD Movies French Euro Channel Series English Star World HD Series English FX HD Series English ITV Choice HD Music English My Music Always HD Music English My Music Tropical HD Music English Channel V International Music English Nat Geo Music HD Music English Clouds TV Music French Mezzo TV HD Lifestyle English ENGLISH Club Lifestyle English Motorvision HD Lifestyle English Gametoon HD Lifestyle French My Zen TV HD Documentary English DocuBOX HD Documentary English Nat Geo Wild HD Documentary English National Geographic HD Documentary English Nat Geo People HD Documentary English RT Documentary HD Documentary English Planet Earth HD Documentary Hindi/English Travel XP HD Kids English Baby TV HD Kids English Duck TV HD Kids English Cartoon Network HD Kids English Boomerang HD Kids Hindi Cartoon Network Hindi Sports English Fast&FunBOX HD Sports English FightBOX HD Sports English WOW TV Sports English Class Horse TV Radio Channels English Hits List Radio Channels English Greatest Hits Radio Channels English Total Hits - UK Radio Channels English Euro Hits Radio Channels English Freedom Radio Channels English Drive Radio -

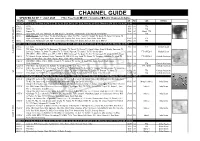

D:\Channel Change & Guide\Chann

CHANNEL GUIDE UPDATED AS OF 1ST JULY 2020 FTA = Free To Air SCR = Scrambled Radio Channels in Italics FREQ/POL CHANNEL SR FEC CAS NOTES ARABSAT 5C at 20.0 deg E: Bom Az 256 El 27, Blr Az 262 El 24, Del Az 253 El 20, Chen Az 263 El 21, Bhopal Az 256 El 21, Cal Az 261 El 11 S 3796 LSRTV 1850 3/4 FTA A 3809 RSSBC TV 1600 2/3 FTA T E 3853 L Espace TV 1388 3/5 Mpeg4 FTA L L 3884 R Iqraa Arabic, ERI TV1, Ekhbariya TV, KSA Sports 2, 2M Monde, El Mauritania. Canal Algeria, Al Maghribia 27500 5/6 FTA I T 3934 L ASBU Bouquet: South Sudan TV, Abu Dhabi Europe, Oman TV, KTV 1, Saudi TV, Sharjah TV, Quran TV, Sudan TV, Sunna TV, E Libya Al Watanya; Holy Quran Radio, Emarat FM, Program One, Radio Quran, Qatar Radio, Radio Oman 27500 7/8 FTA & 3964 L Al Masriyah, Al Masriyah USA, Nile Tv International, Nile News, Nile Drama, Nile Life, Nile Sport, ERTU 1 27500 3/4 FTA C A BADR 5 at 26 deg East: Bom Az 253 El 33.02, Blr Az 259.91 El 29.71, Del 248.93 El 25.47, Chennai Az 260.76 El 26.88, Bhopal Az 252 El 27 B L 4087 L Tele Sahel 3330 3/4 FTA Medium Beam E T 4102 L TNT Niger: Télé Sahel, Tal TV, Espérance TV, Liptako TV, Ténéré TV, Dounia TV, Canal 3 Niger, Canal 3 Monde, Saraounia TV, V Bonferey, Tambara TV, Anfani TV, Labari TV, TV Fidelité, Niger 24, Télé Sahel, Tal TV, Voix du Sahel 20000 2/3 FTA MPEG-4 Medium Beam IRIB: IRIB 1, IRIB 2, IRIB 3 (scr), IRIB 4, IRIB 5, IRINN, Amouzesh TV, Quran TV, Doc TV, Namayesh TV, Ofogh TV, Ifilm, Press 11881 H TV, Varzesh, Pooya, Salamat, Nasim, Tamasha HD, IRIB 3 HD (scr), Omid TV, Shoma TV, Tamasha, Alkhatwar TV, Irkala TV, 27500 5/6 FTA MPEG-4 Central Asia beam Sepehr TV HD; Radio Iran, Radio Payam, Radio Jawan, Radio Maaref etc 11900 V IRIB: IRIB 1, IRIB 2, IRIB 3, IRINN, Amouzesh TV, Salamat TV, Sepehr HD; Radio Iran, Radio Payam, Radio Jawan, Radio Maaref etc. -

Arabic News & Factual Al

stream_name category_name CORONA VIRUS INFO AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL CORONA VIRUS INFO 2 AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL JAZEERA AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL JAZEERA HD AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL JAZEERA MUBASHER AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL ARABIYA AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL ARABIYA AL HADATH AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL ARABY HD AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL BBC ARABIC AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL FRANCE 24 AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL JAZEERA ENGLISH AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL JAZEERA ENGLISH HD AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL JAZEERA DOCUMENTARY AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL JAZEERA DOCUMENTARY HD AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL RT ARAB AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL DW ARABIC AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL TRT ARABIC AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL HURRA AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL BBC WORLD NEWS AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL ALAM NEWS CHANNEL AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL SKY NEWS ARABIA AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL CNBC ARABIYA AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL HIWAR HD AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL GHAD HD AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL AL MUSTAKILA AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL KAIFA AR | ARABIC NEWS & FACTUAL ABUDHABI SPORTS 1 HD AR | ABU DHABI SPORTS ABUDHABI SPORTS 3 HD AR | ABU DHABI SPORTS ABUDHABI SPORTS 4 HD AR | ABU DHABI SPORTS (ARABIC KIDS) AR | ARABIC KIDS MICKEY CHANNEL AR | ARABIC KIDS AL MAJD KIDS HD AR | ARABIC KIDS SPACETOON AR | ARABIC KIDS TAHA KIDS AR | ARABIC KIDS TOYOR BABY AR | ARABIC KIDS ATFAL & MAWAHEB AR | ARABIC KIDS BARAEM KIDS EUROPE AR | ARABIC KIDS TOYOR ALJANNAH AR | ARABIC KIDS ##### BEIN SPORT ##### AR | BEIN SPORT -

05 DI13 Haddad

Dynamiques internationales ISSN 2105-2646 Saïd Haddad Le piratage de TV5 Monde ou l’affirmation d’un discours anti- cyberterroriste Saïd Haddad*, Centre de recherche des écoles de Saint-Cyr Coëtquidan, Université de Rennes 2 – LiRIS (EA 7481) Introduction : Un « impact technique faible » à forte « portée symbolique » Le mercredi 8 avril 2015, la chaine internationale francophone TV5 Monde (250 millions de téléspectateurs) est attaquée par des pirates informatiques. L’attaque intervient le jour du lancement de TV5 Monde Style HD, nouvelle chaîne thématique dédiée à "l'art de vivre à la française", qui a commencé à émettre notamment au Maghreb et au Moyen-Orient. Cette attaque revendiquée entraîne une interruption des programmes de la chaîne qui se traduit par un écran noir à l’antenne. L’infrastructure de diffusion (le multiplexage) est attaquée à 20h50. Les infrastructures principales et de secours sont neutralisées d’un seul coup. D’après le directeur informatique de la chaîne, l’on pense tout d’abord à une panne informatique1. La disparition, quelques minutes plus tard, de l’ensemble des messageries des serveurs indique qu’il s’agit d’une cyberattaque. Afin d’éviter des dégâts supplémentaires, le système informatique est coupé et les diffusions sont interrompues dès 22h. Le directeur général de TV5 annonce aux agences de presse que « nous ne sommes plus en état d’émettre aucune de nos chaînes »2. Parallèlement, le site internet et les comptes twitter et Facebook sont piratés. Des messages de soutien (en arabe, en français et en anglais) à l’organisation Etat islamique (EI) et des messages de propagande sont publiés ainsi qu’un texte adressé au président de la République française (« tu as fait une faute impardonnable »). -

D:\Channel Change & Guide\Chann

CHANNEL GUIDE UPDATED AS OF 1ST OCTOBER 2020 FTA = Free To Air SCR = Scrambled Radio Channels in Italics FREQ/POL CHANNEL SR FEC CAS NOTES INTELSAT-38/AzerSpace2 at 45 deg East: Bom Az 238 El 51, Blr Az 250 El 49, Del 232 El 41, Chennai Az 252 El 46, Bhopal Az 238 El 44 Cal Az 248 El 35 S 11475 V Dialog DTH: Sony Six HD, Discovery World India HD, Star Movies Select HD, Animal Planet HD, AXN East Asia HD, Rugby PassTV HD, Star Sports 1 HD, Sony A Ten2 HD, Star Sports select HD1, Star Sports Select HD2 32000 2/3 DVB-S2/8PSK India Beam T E 11515 V Dialog DTH: CBeebies Asia, Pogo, Cartoon Network, A+ Kids, Nickelodeon, Baby TV, Disney Junior, NGC, Sony BBC Earth, Nat Geo Wild, Animal Planet, L Discovery, Discovery Science, TechStorm, TLC, History TV18, Travel XP, Dsport 1, Sony Ten 1, Ten Cricket, Sony Ten 2 23700 5/6 DVB-S India Beam L I 11555 V Dialog DTH: HGTV Asia, E!, SET India, Sony Max, Star Gold, Colors, Star Plus, Zee TV, Colors Tamil, Sun TV, KTV, Star Vijay, Kalainagar TV, Zee Cinema, UTV T E Movies, B4U Movies, Zee Tamil, Sirippoli, WakuWaku Japan, Celestial Classic Movies, Fashion TV Asia, Hi TV, TVN Asia, WakuWaku Japan South East Asia 27690 3/5 DVB-S India Beam & 11595 V Dialog DTH: Channel One, Rupavahini, Channel Eye, ITN, Vasantham TV, TV Derana, Swarnavahini, Sirasa TV, Shakti TV, TV 1, Hiru TV, TNL, Art, Ada Derana C 24x7, Siyatha TV, Pragna TV, TV Didula, Riddhi TV, Citi Hitz, 7th Circuit, Rangiri TV, Revision TV, UTV Tamil, Udhayam TV, Nenasa TV 10 27690 5/6 DVB-S India Beam A Dialog DTH: Eurosport 1, Outdoor Channel, -

Plf 2019 - Extrait Du Bleu Budgétaire De La Mission : Avances À L'audiovisuel Public

PLF 2019 - EXTRAIT DU BLEU BUDGÉTAIRE DE LA MISSION : AVANCES À L'AUDIOVISUEL PUBLIC Version du 02/10/2018 à 09:29:39 PROGRAMME 847 : TV5 MONDE MINISTRE CONCERNÉ : GÉRALD DARMANIN, MINISTRE DE L’ACTION ET DES COMPTES PUBLICS TABLE DES MATIÈRES Programme 847 : TV5 Monde Présentation stratégique du projet annuel de performances 3 Objectifs et indicateurs de performance 4 Présentation des crédits et des dépenses fiscales 14 Justification au premier euro 17 PLF 2019 3 TV5 Monde PROJET ANNUEL DE PERFORMANCES Programme n° 847 PRÉSENTATION STRATÉGIQUE DU PROJET ANNUEL DE PERFORMANCES Martin AJDARI Directeur général des médias et des industries culturelles Responsable du programme n° 847 : TV5 Monde Le programme 847 a pour objet le financement de la société TV5 Monde. TV5 Monde est une chaîne multilatérale francophone basée à Paris, associant les radiodiffuseurs publics de la France, de la Belgique, de la Suisse, du Canada et du Québec. Sa mission, définie dans la « Charte TV5 Monde », consiste à servir de vitrine à l’ensemble de la Francophonie, à promouvoir la diversité culturelle, à refléter sa dimension multilatérale, à favoriser les échanges de programmes entre les pays francophones et l’exportation internationale de programmes francophones, à être un lieu de coopération entre les radiodiffuseurs partenaires, et veiller à refléter leurs programmes, ainsi qu’à favoriser l’expression de la créativité audiovisuelle et cinématographique francophone. Elle diffuse ses programmes par câble ou satellite dans plus de 200 pays et territoires dans le monde, représentant plus de 350 millions de foyers. Conformément aux dispositions de l’article 1.1 de la charte TV5 Monde, un plan stratégique définissant de façon quadriennale ses axes stratégiques de développement est validé par la conférence des ministres responsables des différents gouvernements bailleurs de fonds de TV5 Monde puis adopté par le conseil administration de la société, composé des représentants des radiodiffuseurs publics des gouvernements partenaires. -

Compte Rendu Mercredi 6 Mai 2015 Commission Des Finances, Séance De 18 Heures 30 De L’Économie Générale Compte Rendu N° 15 Et Du Contrôle Budgétaire

Compte rendu Mercredi 6 mai 2015 Commission des Finances, Séance de 18 heures 30 de l’économie générale Compte rendu n° 15 et du contrôle budgétaire Mission d’évaluation et de contrôle SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 2014-2015 Les financements et la maîtrise de la dépense des organismes extérieurs de langue française Présidence de M. Pascal Terrasse, – Audition, ouverte à la presse, de Mme Anne Grillo, directrice de la coopération culturelle, universitaire et rapporteur de la recherche au sein de la direction générale de la mondialisation, du développement et des partenariats du ministère des affaires étrangères et du développement international, de M. Laurent Gallissot, chef de la mission de la langue française et de l’éducation et de M. Pascal Lemaire, adjoint au chef de la mission des échanges culturels et de l’audiovisuel extérieur. — 2 — M. Pascal Terrasse, président, rapporteur. Notre mission a reçu, dans un premier temps, des représentants de la Délégation aux affaires francophones du ministère des Affaires étrangères, chargée des relations institutionnelles avec les organisations extérieures de la francophonie. Vous nous ferez part, aujourd’hui, de l’expérience et des analyses de votre direction générale, responsable de l’essentiel des contributions budgétaires de l’État et qui organise les partenariats avec le réseau des alliances françaises. Je rappellerai qu’il ne s’agit pas ici d’évoquer la francophonie sous un angle politique mais bien d’un point de vue budgétaire. Mme Anne Grillo, directrice de la coopération culturelle, universitaire et de la recherche au sein de la direction générale de la mondialisation, du développement et des partenariats du ministère des Affaires étrangères et du Développement international.