The Protective Effect of Youths' Attitudes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Bad Things Happen to Good Intentions: the Development and Demise of a Task Force Examining the Drugs- Violence Interrelationship Symposium on Drug Crimes, 63 Alb

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 1999 When Bad Things Happen to Good Intentions: The evelopmeD nt and Demise of a Task Force Examining the Drugs-Violence Interrelationship Symposium on Drug Crimes Deborah W. Denno Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Deborah W. Denno, When Bad Things Happen to Good Intentions: The Development and Demise of a Task Force Examining the Drugs- Violence Interrelationship Symposium on Drug Crimes, 63 Alb. L. Rev. 749 (1999-2000) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/100 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN BAD THINGS HAPPEN TO GOOD INTENTIONS: THE DEVELOPMENT AND DEMISE OF A TASK FORCE EXAMINING THE DRUGS-VIOLENCE INTERRELATIONSHIP Deborah W. Denno* Between 1994-1996, I was one of twenty-eight members of a Drugs->Violence Task Force ("Task Force") created to report to the United States Sentencing Commission specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations concerning the interrelationship (if any) between drugs and violence. 1 The Task Force developed from the * Professor, Fordham University School of Law. B.A., University of Virginia, 1974; M.A., University of Toronto, 1975; Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, 1982; J.D., University of Pennsylvania, 1989. -

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies USSC Testimony Re: MDMA March 15, 2017

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies USSC Testimony re: MDMA March 15, 2017 Rick Doblin, Ph.D., Testimony to US Sentencing Commission Re: MDMA Prepared in collaboration with Ismail L. Ali, JD, and Natalie Lyla Ginsberg, MSW Table of Contents I. The Creation & Criminalization of MDMA ..............................................................2 a. Origin of MDMA..........................................................................................................2 b. History of Criminalization ..........................................................................................3 II. The MDMA Sentencing Guideline Lacks an Empirical Basis .................................5 a. Two federal courts have found the 2001 MDMA Sentencing Guideline to be excessive. .......................................................................................................................5 b. As successfully argued by the ACLU, the present MDMA Sentencing Guideline is based on inaccurate science that exaggerated risks. .............................................6 c. Most commonly-cited MDMA neurotoxicity studies are misleading. ...................10 III. MDMA’s Robust Prosocial Capacity and Low Risk Profile ..................................11 a. MDMA’s Risk Profile ................................................................................................11 b. MDMA literature reviews highlight MDMA’s prosocial capacities .....................12 c. MAPS has sponsored and published FDA-approved drug development studies -

Puppet Play As Interactive Approach in Drug Abuse Prevention

October 2010, Volume 7, No.10 (Serial No.71) US-China Education Review, ISSN 1548-6613, USA Puppet play as interactive approach in drug abuse prevention Diana Nenadic-Bilan, Teodora Vigato (Department of Teacher and Preschool Teacher Education, University of Zadar, Zadar 23000, Croatia) Abstract: The national strategies of drug abuse prevention across Europe have come to recognise that the drugs abuse problem presents a complex set of issues of which there is no simple solution. There is a considerable increase in investment in prevention, treatment and harm-reduction activities and increased focus on supply reduction. School settings are the focus of most attempts to implement effective prevention programmes. Prevention in schools does not only focus on drugs alone, but also includes personal and social skills, often with family involvement and involvement of local community. The school is an ideal setting for drug abuse prevention and development of active and responsible attitudes against drug abuse. Successful school drug-prevention programmes include personal skills training (decision-making, coping and goal-setting), social skills training (assertiveness, resisting peer-pressure), drug education (knowledge about drugs and the consequences of taking them) and developing attitudes (especially correcting misconceptions about peer group drug use). Effective drug education programmes incorporate a range of activities which provide students with relevant factual information, the opportunity to consider their attitudes and values, and the values of others. For effective delivery of prevention programmes, interactive teaching is better than didactic teaching alone. In that sense, the puppet play could be used as an interactive technique. Puppets help the students engage actively in communicating their emotions, opinions and experiences, and learn about the drug abuse problem. -

Licit and Illicit Substance Use Patterns Among University Students In

Schilling et al. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy (2017) 12:44 DOI 10.1186/s13011-017-0128-z RESEARCH Open Access Licit and illicit substance use patterns among university students in Germany using cluster analysis Laura Schilling1, Hajo Zeeb2, Claudia Pischke2, Stefanie Helmer2, Andrea Schmidt-Pokrzywniak3, Ralf Reintjes4, Ulla Walter5, Maria Girbig6, Alexander Krämer7, Andrea Icks8 and Sven Schneider1* Abstract Background: The use of multiple licit and illicit substances plays an important role in many university students’ lives. Previous research on multiple substance use patterns of university students, however, often fails to examine use of different illicit substances and/or hookah. Our objective was to complement and advance the current knowledge about common consumption patterns regarding illicit substances and hookah use in this group. Methods: Students from eight German universities completed an online survey as part of the INSIST study (‘INternet-based Social norms Intervention for the prevention of substance use among STudents’) regarding their consumption of alcohol, tobacco, hookah, cannabis and other illicit substances. Cluster analysis identified distinct consumption patterns of concurrent and non-concurrent substance use and multinomial logistic regressions described key sociodemographic factors associated with these clusters. Results: Six homogeneous groups were identified: ‘Alcohol Abstainers’ (10.8%), ‘Drinkers Only’ (48.2%), ‘Drinkers and Cigarette Smokers’ (14.6%), ‘Cannabis and Licit Substance Users’ (11.2%), ‘Hookah Users with Co-Use’ (9.8%) and ‘Illicit Substance Users with Co-Use’ (5.4%). Illicit substance use clustered with the consumption of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis. Hookah use was regularly associated with alcohol consumption, less commonly associated with tobacco or cannabis use and very rarely associated with use of other illicit substances. -

Cribb, T. Kenneth: Files Folder Title: Drugs – Miscellaneous Box: 3

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Cribb, T. Kenneth: Files Folder Title: Drugs – Miscellaneous Box: 3 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ Donald Ian Macdonald, M. D. Administrator, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration Public Health Service Department of Health and Human Services At the release of the 1987 High School Senior Survey Wednesday, January 13, 1988 Good morning. I'm delighted to see you and, on behalf of the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, to welcome you to this briefing on the 1987 High School Senior Survey of Drug Use. I would like to speak to an issue to which Dr. Bowen referred briefly, and which I believe to be the most telling indicator of our progress to date in putting an end to adolescent drug use and of our prospects for continued gains. I think this particular indicator can be best demonstrated if we juxtapose two elements of the data gathered by Dr . Johnston and his colleagues, so I've drawn up a couple of charts to do this. Let me explain the charts by saying that I speak frequently of three elements critical to success in combatting alcohol and other illicit drug use: knowledge, attitude, and behavior. While other factors are pertinent, accurate information and and appropriate attitudes about drug use should be reflected in drug taking behavior. -

{Download PDF} Theory and Practice of Addiction Counseling 1St Edition

THEORY AND PRACTICE OF ADDICTION COUNSELING 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pamela S Lassiter | 9781506317335 | | | | | Theory and Practice of Addiction Counseling 1st edition PDF Book Tobacco became legal tender. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email sageheoa sagepub. Cultural Issues in Behavioral Addictions. Both drugs may be used as maintenance medications taken for an indefinite period of time , or used as detoxification aids. As the Temperance Movement grew, the message soon became one of abstinence rather than moderation. Once craving has been activated, permissive beliefs "I can handle getting high just this one more time" are facilitated. High b. Rush, a founding father of the U. A final chapter discusses approaches to relapse prevention. According to NIDA, effective treatment must address medical and mental health services as well as follow-up options, such as community or family-based recovery support systems. Once this has been achieved, the counselor coordinates with the addict's family to support them on getting the individual to drug rehabilitation immediately, with concern and care for this person. Chapter Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. Journal of Neurotherapy. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Two Peas in a Pod? Professors: free copies available for adoption consideration Download an e-book copy now or order a print copy. Narcotics Drug Act of b. Concluding chapters discuss effective ways to integrate different treatments in a range of clinical settings. Philosophical underpinnings and key concepts of the theory. Womanist Theory Case Study Response. -

Report on Drug Control in Macao 2005

Report on Drug Control in Macao 2005 Contents z Congratulatory Message z Foreword I. Macao’s Drug Control Policy and Situation of the Drug Problem II. Combat on Drug Crimes Judicial Police III. Prevention and Treatment of Drug Dependence Social Welfare Institute Health Bureau Macao Prison IV. NGO’s Treatment and Rehabilitation Service St. Stephen’s Society-House of Promise Teen Challenge Association of Rehabilitation of Drug Abusers of Macao Christian New Life Fellowship Chong Kong Midway Residence Christian New Life Fellowship – Youth Development Unit Macao Renovation and Mutual Assistance Association Smoking Abstention and Good Health Association V. Research Work VI. External Cooperation Appendix Relevant Drug Control Institutes in Macao/Service Directory 1 Foreword Since the first publication of the Drug Control Report 1991-2000 in 2001, an annual report has been made by the Editing Committee of the Macao Drug Control Report ever since, and its publications are the outcome of co-operation and opinions given by the Committee’s members. We would like to thank the prosecutor counsel of Macao, as well as the Macao Customs for providing valuable information in order to make the content of the reports more consistent. This is the 5th anniversary of the Drug Control Report. Its aim is to let the public review in brief the progress of drug combat from 2001 till 2005. In each section, relevant statistics and information of the last five years will be treated, which will facilitate the understanding of the evolution of the drug problem, as well as the development of related combat in recent years. -

Thesis Final Edit280708

Comparative neuropharmacology of the substituted amphetamines, p-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) & 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) Paul Damian Callaghan B.Sc.(Hons.) Discipline of Pharmacology School of Medicine Faculty of Health Sciences The University of Adelaide August, 2008 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Table of Contents ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................................................................I DECLARATION ..................................................................................................................................................III STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND CONTRIBUTION .......................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................................XI AUXILIARY PUBLICATIONS NOT FOR ASSESSMENT FOR THIS THESIS ................................XIII ABBREVIATIONS, PREFIXES AND SYMBOLS......................................................................................XIV 1. RESEARCH BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. PREVALENCE OF USE (AUSTRALIA AND WORLDWIDE) ........................................................................... 2 1.2. HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF PMA AND MDMA .......................................................................................... -

The Protective Effect of Youths' Attitudes Against Drug Use

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha University of Nebraska at Omaha Masthead Logo DigitalCommons@UNO Criminology and Criminal Justice Faculty School of Criminology and Criminal Justice Publications 12-17-2014 Penny for Your Thoughts? The rP otective Effect of Youths’ Attitudes Against Drug Use in High-Risk Communities Emily M. Wright University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Abigail A. Fagan University of Florida Gillian M. Pichevsky University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/criminaljusticefacpub Part of the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Emily M.; Fagan, Abigail A.; and Pichevsky, Gillian M., "Penny for Your Thoughts? The rP otective Effect of Youths’ Attitudes Against Drug Use in High-Risk Communities" (2014). Criminology and Criminal Justice Faculty Publications. 50. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/criminaljusticefacpub/50 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Footer Logo Criminology and Criminal Justice at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Criminology and Criminal Justice Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YOUTH’S ATTITUDES IN CONTEXT Abstract Individual-level attitudes about drugs are strong predictors of substance use among adolescents, and aggregate-level community norms regarding deviancy and drug use may influence youth attitudes as well as their drug use. This study examined the direct effects of neighborhood norms about deviance, disadvantage, immigrant concentration, and residential stability on youths’ attitudes about drug harmfulness as well as their variety of past month substance use. -

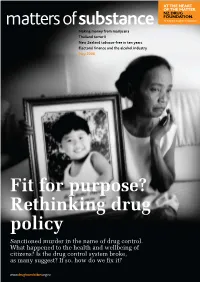

Fit for Purpose? Rethinking Drug Policy Sanctioned Murder in the Name of Drug Control

Making money from marijuana Thailand terror II New Zealand tobacco-free in ten years Electoral finance and the alcohol industry May 2008 Fit for purpose? Rethinking drug policy Sanctioned murder in the name of drug control. What happened to the health and wellbeing of citizens? Is the drug control system broke, as many suggest? If so, how do we fix it? Contents matters of substance May 2008 Features Vol 18 No 2 ISSN 1177-200X 02 Cover story 18 Drugtube – Your guide to New Zealand’s smoking matters of substance is published by the Fit for purpose? the best drug policy videos culture, especially amongst NZ Drug Foundation. All rights reserved. Rethinking drug policy online Mäori. With strong Mäori Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced without prior A review of global drug From motoring gurus testing tikanga and leadership, permission of the NZ Drug Foundation. control at the same time spliffs, to information about Aotearoa can be New Zealand reviews its drug Australian prisoners with tobacco-free. matters of substance invites feedback law presents an opportunity Hep C, to lessons from and contributions. If you’re interested in contributing a guest editorial or article, to develop drug laws and monkeys about drinking 25 Guest Editorial please first contact us: policies relevant for today ‘responsibly’ – we have A view from the House [email protected] brought you a gamut of p +64 4 801 6303 and the future. In a series of The major stumbling block essays, we explore rational splendid variety from what’s to good drug policy is available to view online. -

Ebinder, Reply Comment on Proposed Amendment Sand Issue for Comment on Synthetic Drugs

FEDERAL DEFENDER SENTENCING GUIDELINES COMMITTEE Lyric Office Centre 440 Louisiana Street, Suite 1350 Houston, Texas 77002-1634 Chair: Marjorie Meyers Phone: 713.718.4600 March 10, 2017 Honorable William H. Pryor Acting Chair United States Sentencing Commission One Columbus Circle, N.E. Suite 2-500, South Lobby Washington, D.C. 20002-8002 Re: MDMA/Ecstasy, MDPV, Methylone, Mephedrone, JWH-018, AM-2201 Dear Judge Pryor: While Defenders opposed the Commission’s proposal to make synthetic cannabinoids and cathinones a priority this amendment cycle, Defenders appreciate that the Commission is not trying to act on this complicated issue this year, and instead is engaged in a two-year study. Although we remain concerned that even a two-year study period may not be sufficient to adequately address these “understudied substances,”1 we are pleased that the Commission is not considering these drugs in isolation, and is also examining its approach to MDMA. When the Commission decided in August 2016 to undertake a study of MDMA/Ecstasy, synthetic cannabinoids and synthetic cathinones, it said that it would consider “any amendments to the Guidelines Manual that may be appropriate in light of the information obtained from such a study.”2 Because of the numerous issues that have arisen with drugs not listed in the drug equivalency table, as well as drugs already listed, Defenders believe that the Commission should study not only the specific controlled substances listed in the request for comment, but also other aspects of the drug guideline. Among the issues Defenders encourage the Commission to study are the following: the appropriate role of drug quantity and how direct harms of the drugs at issue should be measured; amending the factors that govern a court’s consideration of analogues and controlled substances not referenced in §2D1.1;3 including an invited departure when the 1 Congressional Research Service, Synthetic Drugs: Overview and Issues for Congress (May 3, 2016) (citing Office of National Drug Control Policy, National Drug Control Strategy 2013, at 10). -

Ebinder, Reply Comment on Proposed Amendment Sand Issue

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT Northern District of New York 206 Federal Building 15 Henry Street Binghamton, New York 13902 Thomas J. McAvoy Senior District Judge January 3, 2017 United States Sentencing Commission One Columbus Circle, N.E. Suite 2-500 Washington, DC 2002-8002 Attention: Public Affairs To the Sentencing Commission: I write in reference to your recent request for public comment on sentencing issues involving MDMA/Ecstasy, synthetic cannabinoids (such as JWH-018 and AM-2201), and synthetic cathinones (such as Methylone, MDPV, and Mephedrone). I currently preside over a case involving methylone distribution. The Defendant retained an expert who produced a report concerning the appropriate marijuana equivalency for methylone. The government responded to that report. After considering those documents, I obtained the report of an independent expert chemist. That expert addressed the questions of substantial similarity as required by USSG '2D1.1. I would be happy to share those reports and the briefs and filings related to them with the Commission. Please contact my law clerk at the address below if you would like to have those documents forwarded to you. Sincerely, Case 1:14-cr-00232-TJM Document 53 Filed 05/24/16 Page 1 of 2 May 24, 2016 via ELECTRONIC FILING Senior Judge Thomas J. McAvoy United States District Court Northern District of New York James T. Foley Courthouse 445 Broadway Albany, New York 12207 Re: United States v. Douglas Marshall, et al Docket: 14-CR-232 Your Honor: As you are aware, this firm represents defendant Douglas Marshall in connection with the above-referenced case.