Zero-Knowledge Proofs of Proximity∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Probabilistically Checkable Proofs Over the Reals

Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science 123 (2005) 165–177 www.elsevier.com/locate/entcs Probabilistically Checkable Proofs Over the Reals Klaus Meer1 ,2 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Syddansk Universitet, Campusvej 55, 5230 Odense M, Denmark Abstract Probabilistically checkable proofs (PCPs) have turned out to be of great importance in complexity theory. On the one hand side they provide a new characterization of the complexity class NP, on the other hand they show a deep connection to approximation results for combinatorial optimization problems. In this paper we study the notion of PCPs in the real number model of Blum, Shub, and Smale. The existence of transparent long proofs for the real number analogue NPR of NP is discussed. Keywords: PCP, real number model, self-testing over the reals. 1 Introduction One of the most important and influential results in theoretical computer science within the last decade is the PCP theorem proven by Arora et al. in 1992, [1,2]. Here, PCP stands for probabilistically checkable proofs, a notion that was further developed out of interactive proofs around the end of the 1980’s. The PCP theorem characterizes the class NP in terms of languages accepted by certain so-called verifiers, a particular version of probabilistic Turing machines. It allows to stabilize verification procedures for problems in NP in the following sense. Suppose for a problem L ∈ NP and a problem 1 partially supported by the EU Network of Excellence PASCAL Pattern Analysis, Statis- tical Modelling and Computational Learning and by the Danish Natural Science Research Council SNF. 2 Email: [email protected] 1571-0661/$ – see front matter © 2005 Elsevier B.V. -

The Complexity Zoo

The Complexity Zoo Scott Aaronson www.ScottAaronson.com LATEX Translation by Chris Bourke [email protected] 417 classes and counting 1 Contents 1 About This Document 3 2 Introductory Essay 4 2.1 Recommended Further Reading ......................... 4 2.2 Other Theory Compendia ............................ 5 2.3 Errors? ....................................... 5 3 Pronunciation Guide 6 4 Complexity Classes 10 5 Special Zoo Exhibit: Classes of Quantum States and Probability Distribu- tions 110 6 Acknowledgements 116 7 Bibliography 117 2 1 About This Document What is this? Well its a PDF version of the website www.ComplexityZoo.com typeset in LATEX using the complexity package. Well, what’s that? The original Complexity Zoo is a website created by Scott Aaronson which contains a (more or less) comprehensive list of Complexity Classes studied in the area of theoretical computer science known as Computa- tional Complexity. I took on the (mostly painless, thank god for regular expressions) task of translating the Zoo’s HTML code to LATEX for two reasons. First, as a regular Zoo patron, I thought, “what better way to honor such an endeavor than to spruce up the cages a bit and typeset them all in beautiful LATEX.” Second, I thought it would be a perfect project to develop complexity, a LATEX pack- age I’ve created that defines commands to typeset (almost) all of the complexity classes you’ll find here (along with some handy options that allow you to conveniently change the fonts with a single option parameters). To get the package, visit my own home page at http://www.cse.unl.edu/~cbourke/. -

The Polynomial Hierarchy

ij 'I '""T', :J[_ ';(" THE POLYNOMIAL HIERARCHY Although the complexity classes we shall study now are in one sense byproducts of our definition of NP, they have a remarkable life of their own. 17.1 OPTIMIZATION PROBLEMS Optimization problems have not been classified in a satisfactory way within the theory of P and NP; it is these problems that motivate the immediate extensions of this theory beyond NP. Let us take the traveling salesman problem as our working example. In the problem TSP we are given the distance matrix of a set of cities; we want to find the shortest tour of the cities. We have studied the complexity of the TSP within the framework of P and NP only indirectly: We defined the decision version TSP (D), and proved it NP-complete (corollary to Theorem 9.7). For the purpose of understanding better the complexity of the traveling salesman problem, we now introduce two more variants. EXACT TSP: Given a distance matrix and an integer B, is the length of the shortest tour equal to B? Also, TSP COST: Given a distance matrix, compute the length of the shortest tour. The four variants can be ordered in "increasing complexity" as follows: TSP (D); EXACTTSP; TSP COST; TSP. Each problem in this progression can be reduced to the next. For the last three problems this is trivial; for the first two one has to notice that the reduction in 411 j ;1 17.1 Optimization Problems 413 I 412 Chapter 17: THE POLYNOMIALHIERARCHY the corollary to Theorem 9.7 proving that TSP (D) is NP-complete can be used with DP. -

Complexity-Adjustable SC Decoding of Polar Codes for Energy Consumption Reduction

Complexity-adjustable SC decoding of polar codes for energy consumption reduction Citation for published version (APA): Zheng, H., Chen, B., Abanto-Leon, L. F., Cao, Z., & Koonen, T. (2019). Complexity-adjustable SC decoding of polar codes for energy consumption reduction. IET Communications, 13(14), 2088-2096. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-com.2018.5643 DOI: 10.1049/iet-com.2018.5643 Document status and date: Published: 27/08/2019 Document Version: Accepted manuscript including changes made at the peer-review stage Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Ex. 8 Complexity 1. by Savich Theorem NL ⊆ DSPACE (Log2n)

Ex. 8 Complexity 1. By Savich theorem NL ⊆ DSP ACE(log2n) ⊆ DSP ASE(n). we saw in one of the previous ex. that DSP ACE(n2f(n)) 6= DSP ACE(f(n)) we also saw NL ½ P SP ASE so we conclude NL ½ DSP ACE(n) ½ DSP ACE(n3) ½ P SP ACE but DSP ACE(n) 6= DSP ACE(n3) as needed. 2. (a) We emulate the running of the s ¡ t ¡ conn algorithm in parallel for two paths (that is, we maintain two pointers, both starts at s and guess separately the next step for each of them). We raise a flag as soon as the two pointers di®er. We stop updating each of the two pointers as soon as it gets to t. If both got to t and the flag is raised, we return true. (b) As A 2 NL by Immerman-Szelepsc¶enyi Theorem (NL = vo ¡ NL) we know that A 2 NL. As C = A \ s ¡ t ¡ conn and s ¡ t ¡ conn 2 NL we get that A 2 NL. 3. If L 2 NICE, then taking \quit" as reject we get an NP machine (when x2 = L we always reject) for L, and by taking \quit" as accept we get coNP machine for L (if x 2 L we always reject), and so NICE ⊆ NP \ coNP . For the other direction, if L is in NP \coNP , then there is one NP machine M1(x; y) solving L, and another NP machine M2(x; z) solving coL. We can therefore de¯ne a new machine that guesses the guess y for M1, and the guess z for M2. -

Simple Doubly-Efficient Interactive Proof Systems for Locally

Electronic Colloquium on Computational Complexity, Revision 3 of Report No. 18 (2017) Simple doubly-efficient interactive proof systems for locally-characterizable sets Oded Goldreich∗ Guy N. Rothblumy September 8, 2017 Abstract A proof system is called doubly-efficient if the prescribed prover strategy can be implemented in polynomial-time and the verifier’s strategy can be implemented in almost-linear-time. We present direct constructions of doubly-efficient interactive proof systems for problems in P that are believed to have relatively high complexity. Specifically, such constructions are presented for t-CLIQUE and t-SUM. In addition, we present a generic construction of such proof systems for a natural class that contains both problems and is in NC (and also in SC). The proof systems presented by us are significantly simpler than the proof systems presented by Goldwasser, Kalai and Rothblum (JACM, 2015), let alone those presented by Reingold, Roth- blum, and Rothblum (STOC, 2016), and can be implemented using a smaller number of rounds. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The current work . 1 1.2 Relation to prior work . 3 1.3 Organization and conventions . 4 2 Preliminaries: The sum-check protocol 5 3 The case of t-CLIQUE 5 4 The general result 7 4.1 A natural class: locally-characterizable sets . 7 4.2 Proof of Theorem 1 . 8 4.3 Generalization: round versus computation trade-off . 9 4.4 Extension to a wider class . 10 5 The case of t-SUM 13 References 15 Appendix: An MA proof system for locally-chracterizable sets 18 ∗Department of Computer Science, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. -

Glossary of Complexity Classes

App endix A Glossary of Complexity Classes Summary This glossary includes selfcontained denitions of most complexity classes mentioned in the b o ok Needless to say the glossary oers a very minimal discussion of these classes and the reader is re ferred to the main text for further discussion The items are organized by topics rather than by alphab etic order Sp ecically the glossary is partitioned into two parts dealing separately with complexity classes that are dened in terms of algorithms and their resources ie time and space complexity of Turing machines and complexity classes de ned in terms of nonuniform circuits and referring to their size and depth The algorithmic classes include timecomplexity based classes such as P NP coNP BPP RP coRP PH E EXP and NEXP and the space complexity classes L NL RL and P S P AC E The non k uniform classes include the circuit classes P p oly as well as NC and k AC Denitions and basic results regarding many other complexity classes are available at the constantly evolving Complexity Zoo A Preliminaries Complexity classes are sets of computational problems where each class contains problems that can b e solved with sp ecic computational resources To dene a complexity class one sp ecies a mo del of computation a complexity measure like time or space which is always measured as a function of the input length and a b ound on the complexity of problems in the class We follow the tradition of fo cusing on decision problems but refer to these problems using the terminology of promise problems -

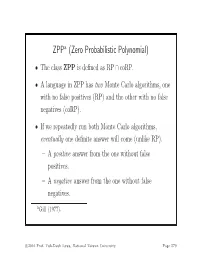

ZPP (Zero Probabilistic Polynomial)

ZPPa (Zero Probabilistic Polynomial) • The class ZPP is defined as RP ∩ coRP. • A language in ZPP has two Monte Carlo algorithms, one with no false positives (RP) and the other with no false negatives (coRP). • If we repeatedly run both Monte Carlo algorithms, eventually one definite answer will come (unlike RP). – A positive answer from the one without false positives. – A negative answer from the one without false negatives. aGill (1977). c 2016 Prof. Yuh-Dauh Lyuu, National Taiwan University Page 579 The ZPP Algorithm (Las Vegas) 1: {Suppose L ∈ ZPP.} 2: {N1 has no false positives, and N2 has no false negatives.} 3: while true do 4: if N1(x)=“yes”then 5: return “yes”; 6: end if 7: if N2(x) = “no” then 8: return “no”; 9: end if 10: end while c 2016 Prof. Yuh-Dauh Lyuu, National Taiwan University Page 580 ZPP (concluded) • The expected running time for the correct answer to emerge is polynomial. – The probability that a run of the 2 algorithms does not generate a definite answer is 0.5 (why?). – Let p(n) be the running time of each run of the while-loop. – The expected running time for a definite answer is ∞ 0.5iip(n)=2p(n). i=1 • Essentially, ZPP is the class of problems that can be solved, without errors, in expected polynomial time. c 2016 Prof. Yuh-Dauh Lyuu, National Taiwan University Page 581 Large Deviations • Suppose you have a biased coin. • One side has probability 0.5+ to appear and the other 0.5 − ,forsome0<<0.5. -

User's Guide for Complexity: a LATEX Package, Version 0.80

User’s Guide for complexity: a LATEX package, Version 0.80 Chris Bourke April 12, 2007 Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 What is complexity? ......................... 2 1.2 Why a complexity package? ..................... 2 2 Installation 2 3 Package Options 3 3.1 Mode Options .............................. 3 3.2 Font Options .............................. 4 3.2.1 The small Option ....................... 4 4 Using the Package 6 4.1 Overridden Commands ......................... 6 4.2 Special Commands ........................... 6 4.3 Function Commands .......................... 6 4.4 Language Commands .......................... 7 4.5 Complete List of Class Commands .................. 8 5 Customization 15 5.1 Class Commands ............................ 15 1 5.2 Language Commands .......................... 16 5.3 Function Commands .......................... 17 6 Extended Example 17 7 Feedback 18 7.1 Acknowledgements ........................... 19 1 Introduction 1.1 What is complexity? complexity is a LATEX package that typesets computational complexity classes such as P (deterministic polynomial time) and NP (nondeterministic polynomial time) as well as sets (languages) such as SAT (satisfiability). In all, over 350 commands are defined for helping you to typeset Computational Complexity con- structs. 1.2 Why a complexity package? A better question is why not? Complexity theory is a more recent, though mature area of Theoretical Computer Science. Each researcher seems to have his or her own preferences as to how to typeset Complexity Classes and has built up their own personal LATEX commands file. This can be frustrating, to say the least, when it comes to collaborations or when one has to go through an entire series of files changing commands for compatibility or to get exactly the look they want (or what may be required). -

The Weakness of CTC Qubits and the Power of Approximate Counting

The weakness of CTC qubits and the power of approximate counting Ryan O'Donnell∗ A. C. Cem Sayy April 7, 2015 Abstract We present results in structural complexity theory concerned with the following interre- lated topics: computation with postselection/restarting, closed timelike curves (CTCs), and approximate counting. The first result is a new characterization of the lesser known complexity class BPPpath in terms of more familiar concepts. Precisely, BPPpath is the class of problems that can be efficiently solved with a nonadaptive oracle for the Approximate Counting problem. Similarly, PP equals the class of problems that can be solved efficiently with nonadaptive queries for the related Approximate Difference problem. Another result is concerned with the compu- tational power conferred by CTCs; or equivalently, the computational complexity of finding stationary distributions for quantum channels. Using the above-mentioned characterization of PP, we show that any poly(n)-time quantum computation using a CTC of O(log n) qubits may as well just use a CTC of 1 classical bit. This result essentially amounts to showing that one can find a stationary distribution for a poly(n)-dimensional quantum channel in PP. ∗Department of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University. Work performed while the author was at the Bo˘gazi¸ciUniversity Computer Engineering Department, supported by Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship project number 626373. yBo˘gazi¸ciUniversity Computer Engineering Department. 1 Introduction It is well known that studying \non-realistic" augmentations of computational models can shed a great deal of light on the power of more standard models. The study of nondeterminism and the study of relativization (i.e., oracle computation) are famous examples of this phenomenon. -

Counting T-Cliques: Worst-Case to Average-Case Reductions and Direct Interactive Proof Systems

2018 IEEE 59th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science Counting t-Cliques: Worst-Case to Average-Case Reductions and Direct Interactive Proof Systems Oded Goldreich Guy N. Rothblum Department of Computer Science Department of Computer Science Weizmann Institute of Science Weizmann Institute of Science Rehovot, Israel Rehovot, Israel [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—We study two aspects of the complexity of counting 3) Counting t-cliques has an appealing combinatorial the number of t-cliques in a graph: structure (which is indeed capitalized upon in our 1) Worst-case to average-case reductions: Our main result work). reduces counting t-cliques in any n-vertex graph to counting t-cliques in typical n-vertex graphs that are In Sections I-A and I-B we discuss each study seperately, 2 drawn from a simple distribution of min-entropy Ω(n ). whereas Section I-C reveals the common themes that lead 2 For any constant t, the reduction runs in O(n )-time, us to present these two studies in one paper. We direct the and yields a correct answer (w.h.p.) even when the reader to the full version of this work [18] for full details. “average-case solver” only succeeds with probability / n 1 poly(log ). A. Worst-case to average-case reductions 2) Direct interactive proof systems: We present a direct and simple interactive proof system for counting t-cliques in 1) Background: While most research in the theory of n-vertex graphs. The proof system uses t − 2 rounds, 2 2 computation refers to worst-case complexity, the impor- the verifier runs in O(t n )-time, and the prover can O(1) 2 tance of average-case complexity is widely recognized (cf., be implemented in O(t · n )-time when given oracle O(1) e.g., [13, Chap. -

63Cu and 19F NMR on Five-Layer Ba2ca4cu5o10(F

PHYSICAL REVIEW B 85, 024528 (2012) High-temperature superconductivity and antiferromagnetism in multilayer cuprates: 63 19 Cu and F NMR on five-layer Ba2Ca4Cu5O10(F,O)2 Sunao Shimizu,* Shin-ichiro Tabata, Shiho Iwai, Hidekazu Mukuda, and Yoshio Kitaoka Graduate School of Engineering Science, Osaka University, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-8531, Japan Parasharam M. Shirage, Hijiri Kito, and Akira Iyo National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Umezono, Tsukuba 305-8568, Japan (Received 22 August 2011; revised manuscript received 2 January 2012; published 20 January 2012) We report systematic Cu and F NMR measurements of five-layered high-Tc cuprates Ba2Ca4Cu5O10(F,O)2.Itis revealed that antiferromagnetism (AFM) uniformly coexists with superconductivity (SC) in underdoped regions, and that the critical hole density pc for AFM is ∼0.11 in the five-layered compound. We present the layer-number dependence of AFM and SC phase diagrams in hole-doped cuprates, where pc for n-layered compounds pc(n) increases from pc(1) ∼ 0.02 in La2−x Srx CuO4 or pc(2) ∼ 0.05 in YBa2Cu3O6+y to pc(5) ∼ 0.11. The variation of pc(n) is attributed to interlayer magnetic coupling, which becomes stronger with increasing n. In addition, we focus on the ground-state phase diagram of CuO2 planes, where AFM metallic states in slightly doped Mott insulators change into the uniformly mixed phase of AFM and SC and into simple d-wave SC states. The maximum Tc exists just outside the quantum critical hole density, at which AFM moments on a CuO2 plane collapse at the ground state, indicating an intimate relationship between AFM and SC.