Download the Entire Issue (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Experimental Music: Redefining Authenticity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xw7m355 Author Tavolacci, Christine Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Experimental Music: Redefining Authenticity A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Contemporary Music Performance by Christine E. Tavolacci Committee in charge: Professor John Fonville, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor Lisa Porter Professor William Propp Professor Katharina Rosenberger 2017 Copyright Christine E. Tavolacci, 2017 All Rights Reserved The Dissertation of Christine E. Tavolacci is approved, and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Frank J. and Christine M. Tavolacci, whose love and support are with me always. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page.……………………………………………………………………. iii Dedication………………………..…………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………..…………………………………………. v List of Figures….……………………..…………………………………………….. vi AcknoWledgments….………………..…………………………...………….…….. vii Vita…………………………………………………..………………………….……. viii Abstract of Dissertation…………..………………..………………………............ ix Introduction: A Brief History and Definition of Experimental Music -

Newsletter.05

College of L e t t e r s & S c i e n c e U n i v e r s i t y D EPARTMENT o f of California B e r k e l e y MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter S e p t e m b e r 2 0 0 5 September 2005 D EAR A LUMNI AND F RIENDS , Note from the Chair reetings to all from the PEOPLE 1–3Update on the last 4 years GUniversity of California, ince the last newsletter, Wye Allanbrook Berkeley, Department of Music, Scompleted her term as department chair, Centenary Celebration this year celebrating our 100th having contributed enormous effort on 100 years of music at Cal birthday! (See article below.) behalf of the new Hargrove Music Library 1, 8–9 This newsletter has always Bonnie Wade building. For the past two years, she has Faculty News Creative accomplishments, been intended as an occasional publication been a Fellow at the National Humanities honors & awards, new to bring to you news of the department. Center in North Carolina. She returns to 4arrivals– Melford6 & Midiyanto For comprehensive details and regular teaching in the 2005–06 academic year. updates please visit our websites: http:// In fall 2003, Allanbrook was succeeded music.berkeley.edu (department); www. by Anthony Newcomb, who served as Gifts to the Department lib.berkeley.edu/MUSI (music library); and department chair for two years. After a 6 www.cnmat.berkeley.edu (Center for New long and distinguished career as teacher Music and Audio Technologies, CNMAT). -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

Helsingin Kaupunginteatteri

HELSINGIN KAUPUNGINTEATTERI Luettelo esityksistä on ensi-iltajärjestyksessä. Tiedot perustuvat esitysten käsiohjelmiin. Voit etsiä yksittäisen esityksen nimeä lukuohjelmasi hakutoiminnolla (yleensä ctrl-F) Walentin Chorell: Sopulit (Lemlarna) Suomennos: Marja Rankkala Ensi-ilta 9.9.1965 Vallila Esityskertoja: 13 Ohjaus: Sakari Puurunen & Kalle Holmberg Ohjaajan assistentti: Ritva Siikala Lavastus: Lassi Salovaara Puvut: Elsa Pättiniemi Musiikki: Ilkka Kuusisto Valokuvaaja: Pentti Auer HENKILÖT: Käthi: Elsa Turakainen/ Lise: Eila Rinne/ Tabitha: Hillevi Lagerstam/ Paula: Pirkko Peltomäki/ Muukalainen: Hannes Häyrinen/ Johann: EskoMannermaa/ Peter: Eero Keskitalo/ Äiti: Tiina Rinne/ Ilse: Heidi Krohn/ Wilhelm: Veikko Uusimäki/ Pappi: Uljas Kandolin/ Günther: Kalevi Kahra/ Tauno Kajander/ Leo Jokela/ Arto Tuominen/ Sakari Halonen/ Stig Fransman/ Elina Pohjanpää/ Marjatta Kallio/ Marja Rankkala: Rakkain rakastaja Ensi-ilta:23.9.1965 YO-talo Esityskertoja: 20 Ohjaus: Ritva Arvelo Apulaisohjaaja: Kurt Nuotio Lavastus ja puvut: Leo Lehto Musiikki: Arthur Fuhrmann Valokuvaaja: Pentti Auer HENKILÖT: Magdalena Desiria: Anneli Haahdenmaa/ Magdalena nuorena: Anja Haahdenmaa/ Ella: Martta Kontula/ Jolanda: Enni Rekola/ David: Oiva Sala/ Alfred: Aarre Karén/ “Karibian Konsuli”: Leo Lähteenmäki/ Rikhard: Kullervo Kalske/ Rafael: Sasu Haapanen/ Ramon: Viktor Klimenko/ Daniel: Jarno Hiilloskorpi/ Pepe: Helmer Salmi/ Anne: Eira Karén/ Marietta: Marjatta Raita/ Tuomari: Veikko Linna/ Tanssiryhmä: Marjukka Halttunen, Liisa Huuskonen, Rauni Jakobsson, Ritva -

Commentary on the Portfolio of Compositions

Commentary on the Portfolio of Compositions Cobi van Tonder Doctor of Philosophy Music Department Trinity College Dublin 2016 Copyright © 2016 Cobi van Tonder i Composition Portfolio Contents 1. String Quartet No 1 - KO (2012/13) 17’ 2. Fata Morgana for Female Choir, Percussion and Computer (2015) 30’ Loss (13’) Arrest 3 (17’) 3. Haute Rorschach microtonal electronic music (2015) 8’30” 4. When all memory is gone microtonal electronic music (2015) 12’ 5. Drift for 12 musicians (2014) 12’ 6. Gala for 8-12 musicians (2015) 5’ 7. Mutation 2 for 4 musicians (2014) 13’ Total: 98’ ii Contents of Accompanying CDs This portfolio is accompanied by 2 audio CDs. Haute Rorschach and When all memory is gone contain important low frequencies and needs to be listened at over loudspeakers that specify Frequency response as 40 Hz -22 kHz, are ideal. Mutation 2 needs to be played through external loudspeakers – the main compositional intention will not come across via headphones. The audio outcomes may be quite diverse as many of the pieces (Haute Rorschach, When all memory is gone, Drift, Gala and Mutation 2) have certain aspects left open to interpretation. CD 1: Audio Recordings Track No. 1. String Quartet No 1 - KO Kate Ellis (Cello), Joanne Quigley (Violin), Paul O'Hanlon (Violin) , Lisa Dowdall (Viola). 2. Fata Morgana – Loss Michelle O’Rourke (Voice), Cobi van Tonder (Computer: Ableton Live). 3. Fata Morgana – Arrest 3 Michelle O’Rourke (Voice), Cobi van Tonder (Computer: Ableton Live). iii CD 2: Audio Recordings Track No. 1. Haute Rorschach Cobi van Tonder (Max/MSP Micro Tuner patch routed to 6 individual Ableton Live Virtual Instruments created with the Ableton Tension physical modeling string synthesizer, Tape Part: Glitch and Reverb). -

Om8 Pro-1 Lorez.Pdf

Other Minds Inc., in association with the Djerassi Residents Artists Program & the Palace of Fine Arts Theatre presents: Other Minds Festival 8 Charles Amirkhanian Artistic Director Featured Composers Ellen Fullman Takashi Harada Lou Harrison Tania León Annea Lockwood Pauline Oliveros Artistic Director’s Welcome 2 Ricardo Tacuchian Manuscript Auction 3 Richard Teitelbaum Randy Weston Music Manuscripts: The Touch of Genius 4 Artist Forum & Concert I 5 Performers Concert I Program Notes 6 African Rhythms Artist Forum & Concert II 9 Thomas Buckner Linda Burman-Hall Concert II Program Notes 10 Sarah Cahill The Art of the Ondes Martenot 12 Circle Trio Demonstration/Discussion/Performance Continuum Concert III Geoffrey Gordon Concert III Program Notes 13 Harmida Piano Trio Masayuki Koga About Artistic Director Charles Amirkhanian 17 Web Radio: Unleashing ‘Sounds Like Tomorrow’ Kronos Quartet Eric Benzant-Feldra Festival 8 Featured Composers 22 & Michael Kudirka Festival 8 Performers 32 The Mexican Guitar Quartet The Other Minds Ensemble Festival Staff and Special Thanks 41 Hiroko Sakurazawa Festival Supporters 42 David Tanenbaum A Gathering of Other Minds Pamela Wunderlich © 2002 Other Minds Inc. All rights reserved. Untitled-3 2-3 2/24/2002, 3:37 PM Welcome to Other Minds Exhibition & Silent Auction “His epitaph could read that he composed music in others’ minds.” -New Yorker, 1992, following the death of composer John Cage. We are delighted to present these score pages by Other Minds he restless investigations of John Cage live on in the spirit of this year’s nine Other Minds 8 composers. We welcome composers, 2001-2002 Season: Tthem and all of you who form the Other Minds community that gathers annually in San Francisco for this celebration of unique compositional achievements. -

Deep Listening, Touching Sound

WHAT IS DEEP LISTENING? What is Deep Listening? There’s more to listening than meets the ear. Pauline Oliveros describes Deep Listening as “listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what one is doing.” Basically Deep Listening, as developed by Oliveros, explores the difference between the involuntary nature of hearing and the voluntary, selective nature – exclusive and inclusive -- of listening. The practice includes bodywork, sonic meditations, interactive performance, listening to the sounds of daily life, nature, one’s own thoughts, imagination and dreams, and listening to listening itself. It cultivates a heightened awareness of the sonic environment, both external and internal, and promotes experimentation, improvisation, collaboration, playfulness and other creative skills vital to personal and community growth. The Deep Listening: Art/Science conference provides artists, educators, and researchers an opportunity to creatively share ideas related to the practice, philosophy and science of Deep Listening. Developed by com- poser and educator Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening is an embodied meditative practice of enhancing one’s attention to listening. Deep Listening began over 40 years ago with Oliveros’ Sonic Meditations and organi- cally evolved through performances, workshops and retreats. Deep Listening relates to a broad spectrum of other embodied practices across cultures and can be applied to a wide range of academic fields and disci- plines. This includes, but not limited to: • theories of cognitive -

Stanford Live Artist Spotlight, Part of CSMA’S 2016-2017 Community Concert Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 16, 2016 CONTACT: Sharon Kenney, Director of Marketing, Community School of Music and Arts 650-917-6800, ext 305; [email protected] Community School of Music and Arts Presents Sarah Cahill, Pianist, January 14 MOUNTAIN VIEW, CA – The Community School of Music and Arts (CSMA) in Mountain View welcomes pianist Sarah Cahill on Saturday, January 14 at 7:30pm. The event will be held in Tateuchi Hall at the Community School of Music and Arts, located at 230 San Antonio Circle in Mountain View. This event is free and open to the public. Seating is limited, so please arrive early. Doors open at 7:00pm. Sarah Cahill’s appearance is a Stanford Live Artist Spotlight, part of CSMA’s 2016-2017 Community Concert Series. Cahill, a star of 21st century classical music, has been called “a sterling pianist and an intrepid illuminator of the classical avant-garde” by the New York Times and “a brilliant and charismatic advocate for modern and contemporary composers” by Time Out New York. The evening’s program will celebrate the lineage of California composers and how they are connected, including Terry Riley’s Fandango on the Heaven Ladder, John Adams’ China Gates, selections from Philip Glass’ Piano Etudes, Henry Cowell’s Exultation, and an unpublished Jig by Lou Harrison, plus Sofia Gubaidulina’s Chaconne. Cahill has commissioned, premiered and recorded numerous compositions for solo piano. Over 40 composers have dedicated works to her including John Adams, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, Julia Wolfe, Yoko Ono and Evan Ziporyn, and she has also premiered pieces by Lou Harrison, Ingram Marshall, Toshi Ichiyanagi, George Lewis, Leo Ornstein and many others. -

Lou Harrison Centennial EVA SOLTES EVA

Please turn off all electronic Photography and audio/video recording devices before entering the in the performance hall are prohibited. performance hall. Lou Harrison Centennial EVA SOLTES EVA DEPARTMENT OF These performances are made possible in part by: PERFORMING ARTS, MUSIC, The P. J. McMyler Musical Endowment Fund AND FILM The Ernest L. and Louise M. Gartner Fund The Cleveland Museum of Art The Anton and Rose Zverina Music Fund 11150 East Boulevard The Frank and Margaret Hyncik Memorial Fund Cleveland, Ohio 44106–1797 The Adolph Benedict and Ila Roberts Schneider Fund The Arthur, Asenath, and Walter H. Blodgett Memorial Fund [email protected] The Dorothy Humel Hovorka Endowment Fund cma.org/performingarts The Albertha T. Jennings Musical Arts Fund #CMAperformingarts Programs are subject to change. Series sponsors: Friday, October 20, 2017 TICKETS 1–888–CMA–0033 cma.org/performingarts Welcome to the PerformingLou Harrison Arts 2017–18 Centennial Cleveland Museum of Art Friday, October 20, 2017, 7:30 p.m. cma.org/performingartsGartner Auditorium, the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Museum of Art’s performing arts series #CMAperformingarts offers a fascinating concert calendar notable for its boundless multiplicity. This year, visits from old friends Chamber Music in the Galleries CIM Organ Studio Wednesday, October 4, 6:00 Sunday, March 11, 2:00 and new bring century-spanning music from around the Mr. Harrison’s Gamelans globe, exploring cultural connections that link the human Butler, Bernstein & the Hot 9 Wu Man & heart and spirit. Wednesday, October 11, 7:30 Huayin Shadow Puppet Band Suite for Violin and Wednesday,Lou Harrison March 21, (1917–2003) 7:30 Lou Harrison Centennial American Gamelan (1973) & Richard Dee In the Galleries Friday, October 20, 7:30 Chamber Music in the Galleries 1. -

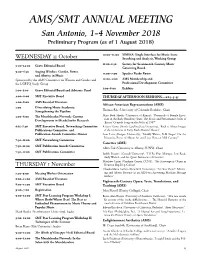

Program (As of 1 August 2018)

AMS/SMT ANNUAL MEETING San Antonio, 1–4 November 2018 Preliminary Program (as of 1 August 2018) 10:00–12:00 SIMSSA: Single Interface for Music Score WEDNESDAY 31 October Searching and Analysis, Working Group 11:00–1:30 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music 9:00–12:00 Grove Editorial Board Governing Board 9:00–6:30 Staging Witches: Gender, Power, 11:00–7:00 Speaker Ready Room and Alterity in Music Sponsored by the AMS Committee on Women and Gender and 12:00–2:00 AMS Membership and the LGBTQ Study Group Professional Development Committee 1:00–8:00 Exhibits 1:00–5:00 Grove Editorial Board and Advisory Panel 2:00–6:00 SMT Executive Board THURSDAY AFTERNOON SESSIONS—2:15–3:45 2:00–8:00 AMS Board of Directors African-American Representations (AMS) 3:00 Diversifying Music Academia: Strengthening the Pipeline Thomas Riis (University of Colorado Boulder), Chair 3:00–6:00 The Mendelssohn Network: Current Mary Beth Sheehy (University of Kansas), “Portrayals of Female Exoti- Developments in Mendelssohn Research cism in the Early Broadway Years: The Music and Performance Styles of ‘Exotic’ Comedy Songs in the Follies of 1907” 6:15–7:30 SMT Executive Board, Networking Committee, Kristen Turner (North Carolina State University), “Back to Africa: Images Publications Committee, and of the Continent in Early Black Musical Theater” Publication Awards Committee Dinner Sean Lorre (Rutgers University), “Muddy Waters, Folk Singer? On the Discursive Power of Album Art and Liner Notes at Mid-Century” 7:30–11:00 SMT Networking Committee Cassettes (AMS) 7:30–11:00