Gladys Nilsson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dan Nadel, Hairy Who? 1966-1969, Artforum, February 2019, P. 164-167 REVIEWS

ARTFORUM H A L E s GLADYS NILSSON Dan Nadel, Hairy Who? 1966-1969, Artforum, February 2019, p. 164-167 REVIEWS FOCUS 166 Dan Nadel OIi "Hall)' Who? 1966-1969 " 11:18 Barry SChwabskyon Raout de Keyser 169 Dvdu l<ekeon the 12th Shangh ai Blennale NEW YORK PARIS zoe Lescaze on Liu vu,kav11ge 186 UllianOevieson Lucla L.a&una Ania Szremski on Amar Kanwar Mart1 Hoberman on Alaln Bublex Jeff Gibson on Paulina OloW5ka BERLIN 172 Colby Chamberialn on Lorraine O'Grady 187 MartinHerberton SteveBlshop OavtdFrankelon lyleAshtonHarrl5 Jurriaan Benschopon Louise Bonnet 173 MlchaelWilsonon HelenMlrra Chloe Wyma on Leonor Finl HAMBURG R11chelChumeron HeddaS1erne JensAsthoffon UllaYonBrandenburg Mira DayalonM11rcelStorr ZURICH 176 Donald Kuspit on ltya Bolotowsky Adam Jasper on Raphaela Vogel Barry Schwabsky on Gregor Hildebrandt 2ackHatfieldon"AnnaAtklns ROME Refracted: Contemporary Works " Francesca Pola on Elger Esser Sasha Frere-Jones on Aur.i Satz TURIN.ITALY Matthew Weinstein on Allen Frame Giorglo\lerzottlon F,ancescoVeuoll WASHINGTON, DC VIENNA 179 TinaR1versRyan011 TrevorPaglen Yuki Higashinoon CHICAGO Wende1ienvanO1denborgh C.C. McKee on Ebony G. Patterson PRAGUE BrienT. Leahy on Robertlostull er 192 Noemi Smolik on Jakub Jansa LISBON 181 Kaira M. cabanas on AlexandreMeloon JuanArauJo ·co ntesting Modernity : ATHENS lnlormallsm In Venezuela, 1955-1975" 193 Cathr)TI Drakeontlle 6thAthensB lennele EL PASO,TEXAS BEIJING 1s2 Che!seaweatherson 194 F!OrlB He on Zhan, Pelll "AfterPosada : Revolutlon · YuanFucaon ZhaoYao LOS ANGELES TOKYO 183 SuzanneHudsonon Sert1Gernsbecher 195 Paige K. Bradley on Lee Kil Aney Campbell on Mary Reid KalleyandP!ltflCkKelley OUBAI GollcanDamifkaz1k on Ana Mazzei TORONTO Dan Adler on Shannon Boo! ABIOJAN, IVORY COAST 196 Mars Haberman on Ouatlera Watts LONDON Sherman Sam on Lucy Dodd SAO PAULO EJisaSchaarot1Flom1Tan Camila Belchior on Clarissa Tossln CHRISTCHURCH. -

Gladys Nilsson MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY | 523 WEST 24TH STREET

MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY 523 West 24th Street, New York,New York 10011 Tel: 212-243-0200 Fax: 212-243-0047 Gladys Nilsson MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY | 523 WEST 24TH STREET GARTH GREENAN GALLERY “Honk! Fifty Years of Painting,” an energizing, deeply satisfying pair of shows devoted to the work of Gladys Nilsson that occupied both Matthew Marks’s Twenty-Fourth Street space, where it remains on view through April 18, and Garth Greenan Gallery, took its title from one of the earliest works on display: Honk, 1964, a tiny, Technicolor street scene in acrylic that focuses on a pair of elderly couples, which the Imagist made two years out of art school. The men, bearded and stooped, lean on canes, while the women sport dark sunglasses beneath their blue-and-chartreuse beehives. They are boxed in by four more figures: Some blank-eyed and grimacing, others skulking under fedoras pulled low. The scene might suggest a vague Kastner, Jeffrey. “Gladys Nilsson.” 58, no. 8, April 2020. Artforum kind of menace were it not for the little green noisemakers dangling from the bright-red lips of the central quartet, marking them as sly revelers rather than potential victims of some unspecified mayhem. The painting’s acid palette and thickly stylized figures obviously owe a debt to Expressionism, whose lessons Nilsson thoroughly absorbed during regular museum visits in her youth, but its sensibility is more Yellow Submarine than Blaue Reiter, its grotesquerie leavened with genial good humor. The Marks portion of the show focuses primarily on the first decade of Nilsson’s career, while Greenan’s featured works made in the past few years, the two constituent parts together neatly bookending the artist’s richly varied and lamentably underappreciated oeuvre. -

Gladys Nilsson Featured in the New York Times

http://nyti.ms/1n3sZC4 ART & DESIGN | ART REVIEW Recognizing a Vibrant Underground ‘What Nerve!’ at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum By KEN JOHNSON SEPT. 25, 2014 In 1962 the film critic Manny Farber published the provocative essay “White Elephant Art and Termite Art,” in which he distinguished two types of artists: the White Elephant artist, who tries to create masterpieces equal to the greatest artworks of the past, and the Termite, who engages in “a kind of squandering- beaverish endeavor” that “goes always forward, eating its own boundaries and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.” While White Elephant artists like Richard Serra, Brice Marden, Jeff Koons and a few other usually male contemporary masters still are most highly valued by the establishment, the art world’s Termite infestation has grown exponentially. They’re everywhere, male and female, busily burrowing in a zillion directions. They’re painting, drawing, doodling, whittling, tinkering and making comic books, zines, animated videos and Internet whatsits — all, it seems, with no objective other than to just keep doing whatever they’re doing. Where did they come from? How did this happen? The history of White Elephant art is well known, that of Termite art much less so, which isn’t surprising given its furtive, centerless nature. So it’s gratifying to see a rousing exhibition at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum that blocks out a significant part of what such a history would entail. “What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art, 1960 to the Present” presents more than 180 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, photographs and videos by 29 artists whom Mr. -

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Lanyon Papers, Circa 1880-2014, Bulk 1926-2013, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Lanyon Papers, circa 1880-2014, bulk 1926-2013, in the Archives of American Art Hilary Price 2016 September 19 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1880-2015 (bulk 1926-2015)......................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1936-2015.................................................................. 10 Series 3: Interviews, circa 1975-2012.................................................................... 24 Series 4: Writings, Lectures, and Notebooks, circa -

Karl Wirsum B

Karl Wirsum b. 1939 Lives and works in Chicago, IL Education 1961 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Solo Exhibitions 2019 Unmixedly at Ease: 50 Years of Drawing, Derek Eller Gallery, NY Karl Wirsum, Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2018 Drawing It On, 1965 to the Present, organized by Dan Nadel and Andreas Melas, Martinos, Athens, Greece 2017 Mr. Whatzit: Selections from the 1980's, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY No Dogs Aloud, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2015 Karl Wirsum, The Hard Way: Selections from the 1970s, Organized with Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Drawings: 1967-70, co-curated by Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008 Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL Winsome Works(some), Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; traveled to Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Herron Galleries, Indiana University- Perdue University, Indianapolis, IN 2007 Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 The Wirsum-Gunn Family Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, Iowa City, IA 1994 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, IL J. -

One Hundred Drawings One Hundred Drawings

One hundred drawings One hundred drawings This publication accompanies an exhibition at the Matthew Marks Gallery, 523 West 24th Street, New York, Matthew Marks Gallery from November 8, 2019, to January 18, 2020. 1 Edgar Degas (1834 –1917) Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (Study for “Alexander and Bucephalus”), c. 1859–60 Graphite on laid paper 1 1 14 ∕8 x 9 ∕8 inches; 36 x 23 cm Stamped (lower right recto): Nepveu Degas (Lugt 4349) Provenance: Atelier Degas René de Gas (the artist’s brother), Paris Odette de Gas (his daughter), Paris Arlette Nepveu-Degas (her daughter), Paris Private collection, by descent Edgar Degas studied the paintings of the Renaissance masters during his stay in Italy from 1856 to 1859. Returning to Paris in late 1859, he began conceiving the painting Alexandre et Bucéphale (Alexander and Bucephalus) (1861–62), which depicts an episode from Plutarch’s Lives. Étude pour “Alexandre et Bucéphale” (Study for “Alexander and Bucephalus”) consists of three separate studies for the central figure of Alexandre. It was the artist’s practice to assemble a composition piece by piece, often appearing to put greater effort into the details of a single figure than he did composing the work as a whole. Edgar Degas, Alexandre et Bucéphale (Alexander and Bucephalus), 1861–62. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, bequest of Lore Heinemann in memory of her husband, Dr. Rudolf J. Heinemann 2 Odilon Redon (1840 –1916) A Man Standing on Rocks Beside the Sea, c. 1868 Graphite on paper 3 3 10 ∕4 x 8 ∕4 inches; 28 x 22 cm Signed in graphite (lower right recto): ODILON REDON Provenance: Alexander M. -

JIM NUTT by David St.-Lascaux

JULY / AUGUST 2010 JIM NUTT by David St.-Lascaux Jim Nutt is back in New York, sans straightjacket. Once a wildman, he was part of Chicago’s Imagist/Hairy Who movement, back in ’66 when Hairy meant huge, when Ed “Big Daddy” Roth was customizing petroleum-powered hot rods with giant ratfinks, chrome pipes, metalflake paint jobs and two-tone flames, shortly after which S. Clay Wilson introduced the maniacal Checkered Demon and the ravishing Star-Eyed Stella. Meanwhile, in New York, the influential, serious works created by Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Rosenquist, and Warhol—also influenced by commercial imagery—were being digested. And what a contrast, using the same cultural raw materials: the Midwest output infantile, maybe; the East Coast oeuvre just possibly uptight. The Hairy Who included graduates of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago: James Falconer; Art Green; Gladys Nilsson, now Nutt’s wife; Suellen Rocca and Karl Wirsum, an Adolf Wölfli doppelgänger. Members of the Imagist movement included Roger Brown, Leon Golub, Ed Paschke (Jeff Koons, then a student, his assistant), Nancy Spero, and H.C. Westermann. The movement’s work was of its time: cartoon garish, rude, clever, heavy on wordplay and sexual innuendo. Hell, it was entirely explicit, and, as demonstrated in Nutt’s “There are Reasons” (1974), in which a Sadie Hawkins Day predacious Jane chases a ragged Dick across a stage, equal opportunity misandristic and misogynistic—although the snood in “Hold Still!! (Please)” (1980-1) is just a wee bit much. The work was also “representational” in the sense that Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is representational: you can decipher it. -

Uncommon Accumulation Bednar Press Release

For Immediate Release: Thursday, December 12, 2019 Contact: Charlotte Easterling 608.257.0158 x 240 [email protected] MMoCA CELEBRATES MAJOR GIFT OF NEARLY 100 WORKS OF CHICAGO IMAGIST ART UNCOMMON ACCUMULATION: THE MARK AND JUDY BEDNAR COLLECTION OF CHICAGO IMAGISM March 14–July 19, 2020 MADISON, WI— To celebrate Mark and Judy Bednar’s transformative gift of Chicago Imagist art from their collection to the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, MMoCA will bring together the works in the museum’s main galleries with the exhibition Uncommon Accumulation: The Mark and Judy Bednar Collection of Chicago Imagism. From March 14 through July 19, 2020, Uncommon Accumulation will showcase the works that have already been gifted to the museum alongside the promised gifts that have been collected by the Bednars over the past 45 years. The gift from the Bednars complements the museum’s existing collection of Chicago Imagism through its inclusion of artworks produced very early in the careers of several of the artists. Formative works by Roger Brown, Robert Lostutter, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Ed Paschke, Christina Ramberg, Barbara Rossi, Karl Wirsum, and Ray Yoshida from the 1960s and 70s—a period when some of the Imagists were still in graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC)—are part of this extraordinary gift. These new additions uphold MMoCA as having one of the largest, and now one of the most comprehensive, collections of Chicago Imagism. The Chicago Imagists were a group of figurative artists who emerged in Chicago in the mid-1960s. Using vibrant color and bold lines, they depicted the human body as grossly distorted and highly stylized. -

The South Side & Beyond

THE INDEPENDENT VOICE OF THE VISUAL ARTS Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York Volume 32 No. 6 July/August 2018 Established 1973 The South Side & Beyond: A Chicago Art Legacy INSIDE Patric McCoy, Pioneering South Side Art Collector Seven Reviews Cover Shows of African-American Artists Cleveland Prepares to Host International Art Triennial $8 U.S. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists-Sponsored Show Features Martyl and (art)n SUBSCRIPTIONS NEW ART EXAMINER IS AVAILABLE FROM THE FOLLOWING CHICAGO OUTLETS: The New Art Examiner has a long history of pro- ducing quality and independent art criticism. 57th Street Books Subscription rates include six issues, print and digi- 1301 E 57th St, Chicago, IL 60637 tal version sent by email. (773) 684-1300 USA/Canada $55 postage incl. ARC Gallery Rest of World $80 postage incl. 2156 N Damen Ave, Chicago, IL 60647 (773) 252-2232 Please send checks, along with your name and Corbett vs Dempsey Gallery address, made payable to: 1120 N Ashland Ave, Chicago, IL 60622 New Art Examiner (773) 278-1664 5542 N. Paulina St. Chicago, IL 60640. USA. Fahlstrtom’s Fresh Fish Market 1258 W Belmont Ave, Chicago, IL 60657 (773) 281-6000 ADVERTISING RATES 2018 Firecat Projects 2124 N Damen Ave, Chicago, IL 60647 FULL PAGE Inside front cover $500 (773) 342-5381 Inside back cover $400 Hilton | Asmus Contemporary FULL PAGE $300 716 N Wells St, Chicago, IL 60654 HALF PAGE – portrait/landscape $200 (312) 475-1788 QUARTER PAGE – (editorial page) $125 Jackson and Junge Gallery (add $25 for inclusion on web site) 1339 N. -

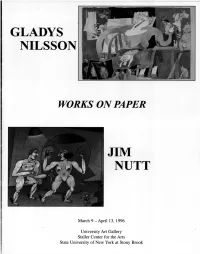

Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt

GLADYS NILSSON WORKS ON PAPER JIM NUTT March 9 - April 13, 1996 University Art GaJJery StaJJer Center for the Arts State University of New York at Stony Brook ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Me.I Pekarslcy, Oepanrnent of Art. for bis assiSlaoCe with this exhibitioo, and to Lynda Hartigan, Curator of Painting and Sculpcurc at the National Museum of American An in Washington, D.C., for contributing her insigbtful catalogue essay. I also want to thank the Phyllis Kind Gallery in Chicago, Ulinois and Vaugbn Kurtz, for their coopera tion and assistance in getting the exhibition from Chicago to Stony Brook. Special thanks are also extended to members of the Staller Center for the Arts staff: Ming Chen, Albert Fong, Vera Phillip-Evans, Lisa Kozlowski, and Alexander Trillo, Gallery Assistants; Erica Fredriben, Aleksandra llcanowicz, Viktoria Paranyuk, Jennifer Rea, and Michelle Wacker, Gallery Interns; Patrick Kelly, Production Manager, Liz Silver, Technical Dmctor, and the Technical Crew, Staller Center, for exhibition lighting; and Mary Balduf, Gallery Secretary. Most of all, I wish to thank Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt for sharing their work with the Stony Brook com munity. Rhonda Cooper Director Photo credits: 0 William H. Bengtson, cover pbocos and ~es 3 (top), S, 6, and 7 0 Jonas Dovydenas page 3 (bottom) Cover: (top) GLADYS NILSSON Me - Myself & I. 1995 Mixed media and watercolor on paper, 12 x 18" (bottom) JIM NUTT I RememhttWbep, 1986 Colored pencil on brown paper, 12~ x 14" © 1996 University An Gallery, Staller Center for the Ans, State University of New York at Stony Brook GLADYS NILSSON AND JIM NUTT: WORKS ON PAPER In 1961 Gladys Nilsson and Jim on paper primarily wi1h dmwing. -

Artforum — April 1St, 2020 Gladys Nilsson At

Gladys Nilsson Matthew Marks Gallery | 523 WEST 24TH ST & Garth Greenan Gallery “Honk! Fifty Years of Painting,” an energizing, deeply satisfying pair of shows devoted to the work of Gladys Nilsson that occupied both Mat- thew Marks’s Twenty-Fourth Street space, where it remains on view through April 18, and Garth Gre- enan Gallery, took its title from one of the earliest Gladys Nilsson, Plain Air, 2018, acrylic and paper on canvas, 40 × 60”. works on display: Honk, 1964, a tiny, Technicolor street scene in acrylic that focuses on a pair of elderly couples, which the Imagist made two years out of art school. The men, bearded and stooped, lean on canes, while the women sport dark sunglasses beneath their blue-and-chartreuse beehives. They are boxed in by four more figures: Some blank-eyed and grimacing, others skulking under fedoras pulled low. The scene might suggest a vague kind of menace were it not for the little green noisemakers dangling from the bright-red lips of the central quartet, marking them as sly revelers rather than potential victims of some unspecified mayhem. The painting’s acid palette and thickly stylized figures obviously owe a debt to Expres- sionism, whose lessons Nilsson thoroughly absorbed during regular museum visits in her youth, but its sen- sibility is more Yellow Submarine than Blaue Reiter, its grotesquerie leavened with genial good humor. The Marks portion of the show focuses primarily on the first decade of Nilsson’s career, while Greenan’s featured works made in the past few years, the two constituent parts together neatly bookending the art- ist’s richly varied and lamentably underappreciated oeuvre. -

Roger Brown, a Leading Painter of the Chicago

Roger Brown, 55, Leading Chicago Imagist Painter, Dies Roberta Smith November 26, 1997 THE NEW YORK TIMES Roger Brown, a leading painter of the Chicago Imagist style, whose radiant, panoramic images were as passionately po- litical as they were rigorously visual, died on Saturday at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta. He was 55 and had homes and studios in Chicago, New Buffalo, Mich., and Carpen- teria, Calif. The cause was liver failure after a long illness, said Phyllis Kind of the Phyllis Kind Gallery, which has represented Mr. Brown since 1970. In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, Mr. Brown was one of a number of artists whose interests and talents coalesced into one of the defining moments in postwar Chicago art. The inspiration for these artists came from European Surrealism, which was prevalent in the city’s public and private collections; contemporary outsider art, which the Imagists helped promote, and popular culture, recently sanctioned by Pop Artists. In addition to Mr. Brown, these artists included Jim Nutt, Ed Paschke, Phil Hanson, Ray Yoshida, Karl Wirsum, Barbara Rossi and Gladys Nilsson, almost all of whom he met as a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and each of whom braided the city’s disparate cultural strands into a distinctive hybrid of figurative styles. Mr. Brown’s hybrid was a powerful combination of flattened, cartoonish images that featured isometric skyscrapers and tract houses, furrowed fields, undulating hills, pillowy clouds and agitated citizens, the latter usually seen in black silhouette at stark yellow windows where they enacted violent or sexual shadow plays.