The Fastest Grand Prix Driver Ever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race Preview 2015 AUSTRALIAN GRAND PRIX 13-15 March 2015

Race Preview 2015 AUSTRALIAN GRAND PRIX 13-15 March 2015 After a short off-season and an intense winter testing CIRCUIT DATA programme, Formula One’s much-anticipated 2015 ALBERT PARK CIRCUIT campaign gets underway this weekend with the sport’s Length of lap: now traditional curtain-raiser, the Australian Grand Prix 5.303km at Melbourne’s Albert Park circuit. Lap record: 1:24.125 (Michael The temporary track is a tricky test for new machinery Schumacher, Ferrari, 2004) Start line/finish line offset: and drivers alike. As with street circuits, the rarely raced 0.000km surface initially provides little grip and evolves steeply Total number of race laps: over the weekend. It’s therefore important for drivers to 58 feed performance in gradually as the surface ‘rubbers Total race distance: in’ and they come to terms with the latest developments 307.574km to machines that are almost fresh off the drawing board. Pitlane speed limits: And with the barriers close and expectation high at the 60km/h in practice, qualifying, season start, Melbourne’s grand prix is always one of and the race the season’s most unpredictable. CIRCUIT NOTES With a number of key driver moves and team ►The kerb on the exit of Turn developments occurring towards the end of last year, Two has been extended. the new season also throws up a host of intriguing DRS ZONE questions. Will four-time champion Sebastian Vettel be ► The DRS zones for this year’s the man to revive Ferrari’s fortunes? Will a new look race will the the same as those used in 2014. -

April 7-9, 2017 Gplb.Com 1

APRIL 7-9, 2017 GPLB.COM 1 2 TOYOTA GRAND PRIX OF LONG BEACH Dear Members of the Media: Welcome to the Roar by the Shore…the 43rd Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach. We've designed this media guide to assist you throughout the weekend, whether it be to reference historical data, information on this year's event or information and statistics on our six weekend races. It also includes a section on transportation, hotels and restaurants to make your stay in Long Beach more efficient and enjoyable. Our three-day weekend is packed with activities on and off the track. In addition to the racing, two concerts will take place: on Friday night at 6:45 p.m., the Tecate Light Fiesta Friday concert will feature popular Mexican rock band "Moderatto," while on Saturday night, "SMG Presents Kings of Chaos Starring Billy Idol, Billy Gibbons and Chester Bennington" will entertain the Grand Prix crowd at the Rock-N-Roar Concert. The Lifestyle Expo, located in the Long Beach Convention & Entertainment Center, will see more than 180,000 Grand Prix fans walk through multiple times. Our annual media luncheon takes place on Thursday, April 6, and will feature drivers from many of the racing series that will be here over the weekend. Media interested in attending should contact us. If you have any questions or particular needs surrounding the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach, please do not hesitate to contact our Public Relations Department at (562) 490-4513 or [email protected]. Our website, gplb.com, can be accessed at any time to find the latest news and information about the Grand Prix, plus the website's Media Center area has downloadable, hi-resolution photos for editorial use. -

Silverstone 11-14 July

Official Formula 1™ Media Kit Formula 1 Rolex British Grand Prix 2019 Silverstone 11-14 July Silverstone Circuit Silverstone Circuit, Northamptonshire NN12 8TN United Kingdom OC E T Tel: 0844 3728 200 www.silverstone.co.uk © 2019 Formula One World Championship Limited, a Formula 1 company. The F1 FORMULA 1 logo, F1 logo, FORMULA 1, F1, FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP, GRAND PRIX, BRITISH GRAND PRIX and related marks are trade marks of Formula One Licensing BV, a Formula 1 company. All rights reserved. The FIA logo is a trade mark of Federation Internationale de l’Automobile. All rights reserved. The F1 logo, FORMULA 1, F1, FIASI FORMULA ONEL WORLDVERSTONE CHAMPIONSHIP, BRITISH GRAND PRIX and 1 related marks are trade marks of Formula One Licensing BV, a Formula 1 company. All rights reserved THURSDAY 11 - SUNDAY 14 JULY 2019 Official Formula 1™ Media Kit Formula 1 Rolex ritish Grand rix 2019 Silverstone 11-14 uly CONTENTS General Information Timetable 04 Silverstone Information Media Contacts 08 Useful Media information 09 Opening hours of media facilities 09 Accreditation Centre and Media Locations map 10 Red Zone Map 11 Pit Garage Allocation 12 Silverstone Circuit Facts 13 FIA Formula 1 World Championship & British Grand Prix 2019 Race Winners 14 Results of 2019 Races 15 Drivers’ Championship Standings (after Austrian GP) 24 Constructors’ Championship Standings (after Austrian GP) 25 FIA Formula 1 World Champions 1950 - 2018 26 British Grand Prix Winners 1950-2018 27 The British Racing Drivers’ Club 29 Silverstone Landmarks 1948 - 2018 30 Silverstone Circuit Silverstone Circuit, Northamptonshire NN12 8TN United Kingdom Tel: 0844 3728 200 www.silverstone.co.uk The F1 logo, FORMULA 1, F1, FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP, BRITISH GRAND PRIX and 2 related marks are trade marks of Formula One Licensing BV, a Formula 1 company. -

From Pit Lanes to Pitch Controls

portfolio FRom PIT LANES to PItcH coNTRols Thierry Boutsen’s grand prix career might have been hampered by bad The Formula 1 that today draws CAPTION luck and uncharacteristically bad continent-sized audiences is a far cry from [ ] cars, but he has found success in the spectacle of the ‘Eighties. In this current his next venture thanks to some of era of highly professional and corporate- his old track friends driven celebrities backed by multi-million- dollar budgets and the highest levels of By Richard Whitehead safety, the names Hamilton, Vettel and Rosberg are among the biggest in sport. The years of the gentleman racer scraping together sponsorship pledges in the hope of securing a race seat are long gone; likewise the sense that anything could happen on track, by drama or catastrophe, has been replaced by whole- race leaders and pit crew technology to measure telemetrics and milliseconds. Thierry Boutsen, a young racing enthusiast who gathered $500,000 in tobacco sponsorship to buy a seat in the Arrows team in 1983, would balk at this current bland era of champions “weighing the percentages” and “taking the positives” from a race. During his decade-long career that saw him race for motorsport’s biggest teams, he would race by the seat of his pants for glory while stuffing away the constant threat of calamity to the back of his mind. Born in Belgium in 1957, Boutsen quickly ascended the racing ladder via the feeder formulas of the late ‘Seventies and 186 early ‘Eighties. ------ By 1987, having finished his three-year F1 187 apprenticeship at Arrows with a reputation top: Thierry Boutsen on the victory podium in Budapest, 1990. -

Lewis the Unbreakable

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE PASSION ABU DHABI GP Issue 159 23 November 2014 Lewis the unbreakable LEADER 3 ON THE GRID BY JOE SAWARD 4 SNAPSHots 8 LEWIS HAMIltoN WORLD CHAMPION 20 IS MAttIAccI OUT AT FERRARI ? 22 DAMON HILL ON F1 SHOWDOWNS 25 FORMULA E 30 THE LA BAULE GRAND PRIX 38 THE SAMBA & TANGO CALENDAR 45 PETER NYGAARD’S 500TH GRAND PRIX 47 THE HACK LOOKS BACK 48 ABU DHABI - QUALIFYING REPORT 51 ABU DHABI - RACE REPORT 65 ABU DHABI - GP2/GP3 79 THE LAST LAP BY DAVID TREMAYNE 85 PARTING SHot 86 The award-winning Formula 1 e-magazine is brought to you by: David Tremayne | Joe Saward | Peter Nygaard With additional material from Mike Doodson | Michael Stirnberg © 2014 Morienval Press. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Morienval Press. WHO WE ARE... ...AND WHAT WE THINK DAVID TREMAYNE is a freelance motorsport writer whose clients include The Independent and The Independent on Sunday newspapers. A former editor and executive editor of Motoring News and Motor Sport, he is a veteran of 25 years of Grands Prix reportage, and the author of more than 40 books on motorsport. He is the only three-time winner of the Guild of Motoring Writers’ Timo Makinen and Renault Awards for his books. His writing, on both current and historic issues, is notable for its soul and passion, together with a deep understanding of the sport and an encyclopaedic knowledge of its history. -

Masters Historic Festival 22 / 23 August 2020 Pit Garage Plan

Masters Historic Festival 22 / 23 August 2020 Pit Garage Plan GARAGE TEAM DRIVER CAR RACE 1 ACCESS TO ASSEMBLY AREA Hall & Hall Lukas Halusa McLaren M23 Masters Historic Formula One 2 Alex Ames Martin Halusa / Lukas Halusa Jaguar E-Type Gentlemen Drivers Classic Team Lotus Lotus 91/5 Masters Historic Formula One 3 Greg Thornton Titan Historic Racing Chevron B8 Masters Historic Sports Cars 4 James Hagan Hesketh 308 Masters Historic Formula One 5 Mirage Engineering Steve Hartley McLaren MP4/1 Masters Historic Formula One 6 Ron Maydon LEC CRP1 Masters Historic Formula One Ian Simmonds Tyrrell 012 Masters Historic Formula One 7 Phil Hall Theodore TR1 Masters Historic Formula One 8 Complete Motorsport Solutions Robert Shaw Chevron B19 Masters Historic Sports Cars 9 Mike Whitaker Lola T70 MK2 Spyder Masters Historic Sports Cars 10 11 Perkins Racing Chris Perkins Surtees TS14 Masters Historic Formula One 12 Forza Historic Racing Jean Lou Rihon Arrows A11 F1 Demo 13 Jonathan Holtzman Tyrrell P-34 Masters Historic Formula One 14 CGA Race Engineering 15 James Hanson March Leyton House F1 Demo 16 MJ Tech John Reaks Benetton B190 F1 Demo 17 KDM Racing Kevin Mason Honda RA 1082 F1 Demo 18 Nine-W Racing Richard Hope Brabham BT59 F1 Demo 19 Team Leos Jonathan Mitchell Chevron B19 Masters Historic Sports Cars 20 James Claridge James Claridge / Gonzalo Gomez Chevron B23 Masters Historic Sports Cars Chevron B8 Masters Historic Sports Cars 21 360 Racing Andrew & Mark Owen Ford Lotus Cortina Masters Pre-66 Toruing Cars John Sheldon Chevron B16 Masters Historic -

BRDC Bulletin

BULLETIN BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB DRIVERS’ RACING BRITISH THE OF BULLETIN Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB Volume 30 No 2 2 No 30 Volume • SUMMER 2009 SUMMER THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB President in Chief HRH The Duke of Kent KG Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 President Damon Hill OBE CONTENTS Chairman Robert Brooks 04 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 56 OBITUARIES Directors 10 Damon Hill Remembering deceased Members and friends Ross Hyett Jackie Oliver Stuart Rolt 09 NEWS FROM YOUR CIRCUIT 61 SECRETARY’S LETTER Ian Titchmarsh The latest news from Silverstone Circuits Ltd Stuart Pringle Derek Warwick Nick Whale Club Secretary 10 SEASON SO FAR 62 FROM THE ARCHIVE Stuart Pringle Tel: 01327 850926 Peter Windsor looks at the enthralling Formula 1 season The BRDC Archive has much to offer email: [email protected] PA to Club Secretary 16 GOING FOR GOLD 64 TELLING THE STORY Becky Simm Tel: 01327 850922 email: [email protected] An update on the BRDC Gold Star Ian Titchmarsh’s in-depth captions to accompany the archive images BRDC Bulletin Editorial Board 16 Ian Titchmarsh, Stuart Pringle, David Addison 18 SILVER STAR Editor The BRDC Silver Star is in full swing David Addison Photography 22 RACING MEMBERS LAT, Jakob Ebrey, Ferret Photographic Who has done what and where BRDC Silverstone Circuit Towcester 24 ON THE UP Northants Many of the BRDC Rising Stars have enjoyed a successful NN12 8TN start to 2009 66 MEMBER NEWS Sponsorship and advertising A round up of other events Adam Rogers Tel: 01423 851150 32 28 SUPERSTARS email: [email protected] The BRDC Superstars have kicked off their season 68 BETWEEN THE COVERS © 2009 The British Racing Drivers’ Club. -

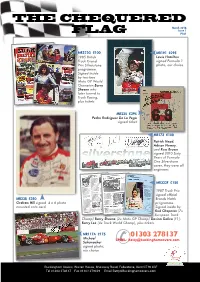

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

27 Patrick Tambay – the Ferrari Years by Massimo Burbi with Patrick Tambay

27 Patrick Tambay – The Ferrari Years By Massimo Burbi with Patrick Tambay Photographs by Paul‐Henri Cahier Foreword by Alain Prost Publication Date: 5th May 2016 Hardback, RRP: £60.00, ISBN: 978‐1‐910505‐12‐0 Format 280x235mm, Page Extent: 300pp, Over 175 photographs “This fascinating book is an emotional rollercoaster of a story about two years that changed Patrick’s career and his entire life.” Alain Prost This is the emotional story of Patrick Tambay’s rollercoaster Formula 1 ride with Ferrari. The saga began in 1982 with the tragedy of his friend and fellow driver Gilles Villeneuve’s death in the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder and then unfolded as Tambay took Villeneuve’s place in car number 27, achieved race victories and, as the 1983 season developed, fought for the World Championship. Told in 27 chapters, this is a tale not only of Formula 1 in those colourful years but also a rare and revealing account of life insider Maranello in the twilight of the Enzo Ferrari era, supported by magnificent photographs by Paul‐Henri Cahier. Highlights: British GP, 1982: At Brands Hatch Tambay’s second race for Ferrari beings his first‐ever podium finish, in his 51st Formula 1 start German GP, 1982: After team‐mate Didier Pironi’s career‐ending crash during practice at Hockenheim, Tambay lifts his sombre Ferrari team with his first Fomula 1 win. Italian GP, 1982: In front of Ferrari’s emotional home crowd at Monza, Tambay finishes second, with the great Mario Andretti, his team‐mate for this one race, behind him in third place. -

SPA-FRANCORCHAMPS 30 AUG-01 SEP | OFFICIAL MEDIA KIT Summary

SPA-FRANCORCHAMPS 30 AUG-01 SEP | OFFICIAL MEDIA KIT Summary Welcome to Spa-Francorchamps........................................................................... 2 FIA - Belgian GP: Map ........................................................................................ 3 Timetable ............................................................................................................. 4-5 Track Story .......................................................................................................... 6-7-8 Useful information ............................................................................................... 9-10 Media centre operation ........................................................................................ 11 Photographer’s area operation ............................................................................ 12 Press conferences ................................................................................................ 13 Race Track Modifications ...................................................................................... 14 Race Track Responsabilities............................................................................... 15 Track information map ......................................................................................... 16 Track map ............................................................................................................ 17 Paddock map ...................................................................................................... -

For Immediate Release Mouser Electronics Gears up with Indycar Champion Tony Kanaan for Grand Prix at Long Beach

1000 N. Main Street Mansfield, TX 76063, USA mouser.com (817) 804-3800 For Immediate Release Mouser Electronics Gears Up with IndyCar Champion Tony Kanaan for Grand Prix at Long Beach April 11, 2012 – Mouser Electronics, Inc., regarded as a top design engineering resource and global distributor for semiconductors and electronic components, today announced racing preparations are in top gear for the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach, CA. where IndyCar champion Tony Kanaan will drive the No. 11 Mouser Electronics/GEICO/KV Racing Technology Chevrolet/Firestone IndyCar on April 15. The Long Beach race signals the green flag for Mouser as it launches into the 2012 IndyCar season. Mouser first set its sights on IndyCar sponsorship last year as an innovative way to communicate the company’s drive for high-performance and speed, and as a high-tech platform to showcase its valued supplier partnerships. Joining Mouser as co-sponsors are TTI, Inc, Murata, Molex, TE Connectivity, Phoenix Contact, Littelfuse, KEMET, Ohmite, Hammond, Harwin, Digi, ebm-papst, Omron, BIVAR, Fluke, and Amphenol. After a record- breaking 2011 debut, Mouser is eagerly racing into the new Indy season alongside its IndyCar partners and Kanaan in the driver’s seat. The infamous race spans 167 miles of adrenaline-filled track. Ever since its commencement in 1975, the track at Long Beach has seen decades of high-intensity, high-speed duels between some of the top names in IndyCar racing, such as the 1977 race where Mario Andretti avoided a first-lap, multi-car collision and went on to out-duel Formula One stars Jody Scheckter and Niki Lauda to become the first American to win a F/One race in a U.S. -

Do You Remember… Mario Andretti's Superb Monza Comeback

LATEST / FEATURE Do you remember… Mario Andretti’s superb Monza comeback ITALY Formula1.com 31 Aug 2015 There has been a plethora of memorable stand-in performances in F1 racing’s rich history, but for many Mario Andretti’s emotional cameo for Ferrari at the 1982 Italian Grand Prix remains the finest of them all… 0:00 / 0:00 © LAT Photographic “Did I accept as a favour to Mr Ferrari? Well, sure, up to a point. But mainly I did it as a favour to me! Jesus, what kind of guy can say no to Ferrari at Monza?" Mario Andretti had been out of F1 proper for the best part of a year, racing IndyCars in his homeland, when he received the call from the Old Man. Sure, he had commitments stateside, and no, his last Grand Prix outing - a one-off appearance for Williams at Long Beach earlier in the 1982 season - had not gone at all smoothly, but how could he turn down the chance to race for Ferrari at Monza, the very same circuit where, as a 14- year-old, he’d screamed himself hoarse supporting Prancing Horse star Alberto Ascari? The answer was simple: he couldn’t. Andretti’s Monza invitation had come amid desperate times for the Scuderia, who’d lost talismanic star Gilles Villeneuve to a fatal crash at Zolder in May and then seen his championship-leading team mate Didier Pironi suffer what looked to be career-ending injuries in another horrific shunt at Hockenheim barely three months later. To make matters worse, Patrick Tambay, the man with the unenviable task of filling Villeneuve’s vaunted number 27 cockpit, had been forced to pull out of the most recent round at Dijon because of severe back pain.