Fire Management Today Is Published by the Forest Service of the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Fire Siege 2007 an Overview Cover Photos from Top Clockwise: the Santiago Fire Threatens a Development on October 23, 2007

CALIFORNIA FIRE SIEGE 2007 AN OVERVIEW Cover photos from top clockwise: The Santiago Fire threatens a development on October 23, 2007. (Photo credit: Scott Vickers, istockphoto) Image of Harris Fire taken from Ikhana unmanned aircraft on October 24, 2007. (Photo credit: NASA/U.S. Forest Service) A firefighter tries in vain to cool the flames of a wind-whipped blaze. (Photo credit: Dan Elliot) The American Red Cross acted quickly to establish evacuation centers during the siege. (Photo credit: American Red Cross) Opposite Page: Painting of Harris Fire by Kate Dore, based on photo by Wes Schultz. 2 Introductory Statement In October of 2007, a series of large wildfires ignited and burned hundreds of thousands of acres in Southern California. The fires displaced nearly one million residents, destroyed thousands of homes, and sadly took the lives of 10 people. Shortly after the fire siege began, a team was commissioned by CAL FIRE, the U.S. Forest Service and OES to gather data and measure the response from the numerous fire agencies involved. This report is the result of the team’s efforts and is based upon the best available information and all known facts that have been accumulated. In addition to outlining the fire conditions leading up to the 2007 siege, this report presents statistics —including availability of firefighting resources, acreage engaged, and weather conditions—alongside the strategies that were employed by fire commanders to create a complete day-by-day account of the firefighting effort. The ability to protect the lives, property, and natural resources of the residents of California is contingent upon the strength of cooperation and coordination among federal, state and local firefighting agencies. -

2020 Annual Fire Report

Northwest Annual Fire Report 2020 Northwest Interagency Coordination Center Portland, OR Page intentionally left blank TABLE of CONTENTS | NWCC Mission TABLE of CONTENTS TABLE of CONTENTS............................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY INFORMATION ..................................................................................................... 3 NWCC Mission................................................................................................................................3 NWCC Annual Fire Report General Information ...............................................................................3 NWCC ACCOMPLISHMENTS ................................................................................................... 4 A Review of 2020 ...........................................................................................................................4 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NWCC Staff & Organization .................................................................................................................................. 5 Organization: Administration ................................................................................................................................ 5 FIRE SEASON OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................... -

Fire Safety News LAUNCH ALL AIRCRAFT !

Postal Customer PRSRT STD U.S. Postage Escondido, CA 92026 PAID Permit No. 273 Escondido, CA Fire Safety News ECRWSS Serving the communities of Castle Creek, Champagne Village, Deer Springs, West Lilac, Hidden Meadows, Jesmond Dene, Rimrock, and the Welk Resort Volume 5, No. 2 www.DeerSpringsFireSafeCouncil.com Summer, 2008 LAUNCH ALL AIRCRAFT ! CAL FIRE RAMONA AIR ATTACK BASE DURING THE WITCH CREEK FIRE, OCTOBER 2007 The following fire scenario is fictional but could all too easily become a The single digit humidity, high winds, and extremely dry or dead vegetation create reality in our Fire District. It came very close to happening on May 16, 2008 on the ideal conditions for a rapidly moving fire that will threaten lives and property, eastern side of Moosa Canyon. When it does happen, we can all be thankful for the most prominently along the Moosa Canyon Ridge. experience, training, preparation, and discipline of CAL FIRE Air Operations, the CAL FIRE HeliTack Crew Members and the Sheriff’s Office ASTREA Helicop- Within seconds, CAL FIRE Monte Vista dispatches a full response of fire engines, ter pilots who partner with the CAL FIRE personnel in the air and on the ground. water tankers, ground attack crew, and bulldozers. It also orders “LAUNCH These brave men and women put their lives on the line, day in and day out, to save ALL AIRCRAFT” from the San Diego Region. This order sets in to motion a lives and property within our District, the County, and the great State of California. sequence of events that has been anticipated, trained, practiced and performed over We are fortunate to have these resources available to us combined with their strong the course of many years by CAL FIRE Air Operations. -

Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019

REVIEW OF CALIFORNIA WILDFIRE EVACUATIONS FROM 2017 TO 2019 STEPHEN WONG, JACQUELYN BROADER, AND SUSAN SHAHEEN, PH.D. MARCH 2020 DOI: 10.7922/G2WW7FVK DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R Wong, Broader, Shaheen 2 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UC-ITS-2019-19-b N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019 March 2020 6. Performing Organization Code ITS-Berkeley 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report Stephen D. Wong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3638-3651), No. Jacquelyn C. Broader (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3269-955X), N/A Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3350-856X) 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Institute of Transportation Studies, Berkeley N/A 109 McLaughlin Hall, MC1720 11. Contract or Grant No. Berkeley, CA 94720-1720 UC-ITS-2019-19 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period The University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Covered www.ucits.org Final Report 14. Sponsoring Agency Code UC ITS 15. Supplementary Notes DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R 16. Abstract Between 2017 and 2019, California experienced a series of devastating wildfires that together led over one million people to be ordered to evacuate. Due to the speed of many of these wildfires, residents across California found themselves in challenging evacuation situations, often at night and with little time to escape. These evacuations placed considerable stress on public resources and infrastructure for both transportation and sheltering. -

Southern California Fires

Lassen & Plumas National Forests Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) Post-Fire BAER Assessment August 27, 2021 BAER Information: (707) 853-4243 PHASE 1--DIXIE POST-FIRE BAER SOIL BURN SEVERITY MAP RELEASED Due to the large size and continual active burning of the Dixie Fire, the Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) team divided the burned area into two phases for their assessment and analysis. BAER specialists recently completed their data gathering and analysis for Phase 1 of the Dixie burned area to produce a Phase 1 soil burn severity (SBS) map on August 25—analyzing 365,678 acres. The map and the data display SBS categories of unburned/very low, low, moderate, and high. Approximately 43% of the 365,678 acres are either unburned/very low and/or low soil burn severity, while 52% sustained a moderate soil burn severity and only about 5% identified as high soil burn severity. The SBS map also shows the acreage for each of the landowners for the 365,678 acres in the Phase 1 assessment to be: 176,460 acres for the Plumas National Forest; 93,466 acres for the Lassen National Forest; 94,648 acres of private/unknown lands; 889 acres for the State of California-Department of Fish and Game; 98 acres for the USDI Bureau of Land Management; 67 acres for the USDI Bureau of Indian Affairs; and 50 acres for the State of California-Lands Commission. The low category of soil burn severity indicate that there was only partial consumption of fine fuels and litter coverage remains relatively intact on the soil surface. -

Draft DRECP and EIR/EIS – Appendix R1, Data Supporting Volume

Appendix R1.22 Public Safety and Services This appendix includes 5 tables that present airports, fire stations, police stations, landfills and schools within the Plan Area. Draft DRECP and EIR/EIS APPENDIX R1.22. PUBLIC SAFETY AND SERVICES Appendix R1.22 Public Safety and Services Table R1.22-1 Airports Within and Near the Plan Area Map Key Airport Airport Land use Compatibility Plan 1 Agua Dulce Airpark 2 Apple Valley Town of Apple Valley Airport Comprehensive Land Use Compatibility Plan. Prepared by the Town of Apple Valley. March 1995. 3 Avi Suquilla 4 Banning Municipal 5 Barstow-Daggett Airport Comprehensive Land Use Plan, Barstow-Daggett Airport. San Bernardino County. May 1992. 6 Bermuda Dunes 7 Big Bear City Airport Comprehensive Land Use Plan, Big Bear City Airport. San Bernardino County. February 1992. 8 Bishop 9 Blythe 10 Brawley Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan, Imperial County Airports. Imperial County Airport Land Use Commission. June 1996. 11 Cable Cable Airport Comprehensive Airport Land Use Plan. West Valley Planning Agency Airport Land Use Commission. December 9, 1981. 12 Calexico International Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan, Imperial County Airports. Imperial County Airport Land Use Commission. June 1996. 13 General WM J Fox Airfield 14 Hesperia Comprehensive Land Use Plan, Hesperia Airport. San Bernardino County Airport Land Use Commission. Prepared by Ray A. Vidal Aviation Planning Consultant. January 1991. 15 Imperial County Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan, Imperial County Airports. Imperial County Airport Land Use Commission. June 1996. 16 Inyokern (Kern County) Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan. County of Kern. March 29, 2011. 17 Lake Havasu City 18 Laughlin Bullhead International 19 Mojave (Kern County) Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan. -

French Fire Update – September 5, 2021

Fire Information: 760-515-7922 (8am to 8pm) Inciweb: https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7813/ French Fire Update – September 5, 2021 Acreage: 26,493 Containment: 52% Total Personnel: 1,112 The French Fire started on Wednesday, August 18, west of Lake Isabella in Kern County, and has now burned 26,493 acres with 52 percent containment. A National Incident Management Team (NIMO) is managing the fire, integrated with Great Basin IMT 6 and coordinating closely with the Bureau of Land Management, Sequoia National Forest, and Kern County Fire Department in Unified Command. ● Smoke may be visible today as crews work to complete burnout operations in the Cedar Creek and Alder Creek area using a combination of ground and aerial resources. Crews are constructing direct handline north of Red Mountain from Bear Creek to Alder Creek. ● On the north side of the fire, crews continue to mop up, seeking out and eliminating any remaining heat sources that could threaten the line. ● The Structure Group is patrolling and mopping up around infrastructure within the fire’s interior, including Alta Sierra, Shirley Meadows, the Shirley Peak communication hub, and the Southern California Edison 66kV sub-transmission lines north of Hwy 155. These crews are also cutting down unsafe (hazard) trees and preparing the areas for residents to return. ● Crews are successfully mopping up to the north from Basket Pass to Evans Meadow which allowed for an increase in containment in this area. ● The east side of the fire is looking very good. Crews will continue to mop up and patrol. ● Very dry conditions predicted into next week. -

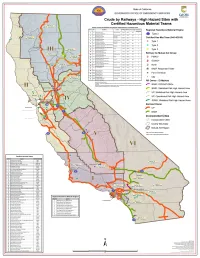

Haz Mat Unit Assignments

State of California GOVERNOR'S OFFICE OF EMERGENCY SERVICES Cal PES GOVERNOR'S OFFICE OF EMERGENCY SERVICES Crude by Railways - High Hazard Sites with Certified Hazardous Material Teams REGULATIONS GOVERNING RAILROAD OPERATIONS AT DEFINED SITES Site No. RR Site Name County MP Begin MP End Total Length Statistical / Regional Hazardous Material Engine Operational 1 UP Coast Subdivision San Luis Obispo 235.0 249.0 14.0 S (formerly SP Coast Line) Type 2 3 UP Yuma Subdivision San Bernardino/ 535.0 545.0 10.0 S (formerly Yuma Line) Riverside 4 UP Yuma Subdivision Riverside 586.0 592.0 6.0 S Certified Haz-Mat Team (04/14/2016) (formerly Yuma Line) 6 UP Yuma Subdivision San Bernardino/ 542.6 589.0 46.4 0 (formerly Yuma Line) Riverside Type 1 9 UP Black Butte Subdivision Siskiyou 322.1 332.6 10.5 S (formerly Shasta Line, Black Butte District) 10 UP Black Butte Subdivision Siskiyou 322.1 338.5 16.4 0 Type 2 (formerly Shasta Line, Black Butte District) 12 UP Roseville Subdivision Placer 150.0 160.0 10.0 s (formerly Roseville District) Type 3 16 UP Mojave Subdivision Kern 335.0 359.9 24.9 s (formerly Bakers fie Id Line) Refinery by Mutual Aid Group 19 UP Mojave Subdivision San Bernardino 463.0 486.0 23.0 0 (formerly Bakersfield Line) 22 UP Canyon Subdivision Butte 234.0 240.0 6.0 s PMAO (formerly Feather River Division) 23 UP Canyon Subdivision Plumas 253.0 282.0 29.0 s (formerly Feather River Division) SCIMO 25 UP Canyon Subdivision Butte/Plumas 232.1 319.2 87.1 0 (formerly Feather River Division) 26 BNSF Gateway Subdivision Plumas 178.0 188.0 10.0 -

SQF Complex Incident Update Date: 10/8/2020

SQF Complex Incident Update Date: 10/8/2020 SQF Complex Contact Information Information Line: (559) 697-5148, 8 AM-8 PM Website: inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/7048/ Email: [email protected] @sequoiaforest @sequoiakingsnps @inyo_nf Incident Information: Start / Report Date: 8/19/20 Size: 162,952 acres Containment: 65 % Cause: Lightning Location: 25 miles N of Injuries: 17 Structures Destroyed: 228 Kernville, CA Resources: Helicopters: 8 Engines: 51 Hand Crews: 18 Water Tenders: 11 Total Personnel: 749 Dozers: 21 Current Situation: The uncontained fire’s edge to the north continues to burn actively. Heavy vegetation, snags, and steep terrain make it difficult to access the fires edge. Threats to infrastructure on Case Mountain, the Hockett Ranger Station, Peck’s Cabin, Buffalo Cabin, several sequoia groves and wilderness values within Sequoia National Park continue. Hockett Meadow ranger station and other structures in South Fork are being prepped for fire protection wrap. Crews are working to stop the fire from spreading and will focus on securing the perimeter and building contingency line along Mineral King Road to Case Mountain. As the temperatures start to cool and the smoke begins to clear, fire activity is expected to increase. The potential for smoke columns starting to form near Homers Nose may be seen in the South Fork and Three Rivers areas. With clear visibility, there will be an increased use of aircraft and helicopters to focus on dropping water and fire retardant in the areas most at risk. Tulare County Sheriff’s Office has issued an evacuation order on October 6 for everything south of the intersection of the Cinnamon Canyon Road and South Fork Drive, including Cinnamon Canyon. -

Southern California Fires

Cleveland National Forest Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) Post-Fire BAER Assessment September 22, 2020 BAER Information: (707) 853-4243 PREPARING FOR RAINSTORMS While many wildfires cause minimal damage to the land and pose few threats to the land or people downstream, some fires cause damage that requires special efforts to prevent problems afterwards. Wildfire increases the potential for flooding, post-fire soil erosion and debris flows that could impact homes, structures, campgrounds, aquatic dependent plants and animals, roads, and other infrastructure within, adjacent to, and downstream from the burned area. Post-fire watershed conditions will naturally receive and transport water and sediment differently than during pre-fire conditions. Monsoonal storms bring heavy rain and rapid runoff from burned areas. Residents and visitors should remain alert to weather events and plan ahead when travelling along roads and trails within and downstream from the burned areas on the Cleveland National Forest (NF). The Forest Service Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) team working with the Cleveland NF to assess post fire conditions of the watersheds on federal land that were burned in the Valley Fire. The BAER assessment team identifies potential emergency threats to critical values-at-risk and recommends emergency stabilization response actions that are implemented on federal lands to reduce potential threats. For values and resources potentially impacted off National Forest System lands, one of the most effective BAER strategies is its interagency coordination with local cooperators who assist affected businesses, homes, and landowners prepare for rain events. The Forest Service and Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) work together and coordinate with other federal, state, and local agencies, and counties that assist private landowners in preparing for increased run-off and potential flooding. -

1 Welcome to Santa Monica Mountains

National Park Service Southern California Fire Ecology U.S. Department of the Interior Wildfire Walkabout Santa Monica Mountains High School Teacher Guide National Recreation Area WELCOME Welcome to Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area Southern California Fire Ecology: Wildfire Walkabout The purpose of this guide is to prepare you and your students for your trip to the Santa Monica Mountains. This field trip is self-led. Please read this guide carefully and if you will be visiting, contact the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area (SMMNRA) education team at [email protected]. FIELD TRIP LOCATION The field trip can take place in any recent burn scar in your area or the Santa Monica Mountains. Suggested sites within the park include Paramount Ranch, Rancho Sierra Vista/Satwiwa, Circle X Ranch, Rocky Oaks, Peter Strauss Ranch, or Solstice Canyon. However, you must contact the park to make sure these sites are accessible and available for a field trip by calling (805) 370-2301 or email [email protected]. As this is a teacher-led field trip please feel free to visit any location that is convenient to you that has been affected by a recent wildfire. You may use or modify any of the activities suggested in this program to your needs. DIRECTIONS For directions to the sites above, call (805) 370-2301 or visit https://www.nps.gov/samo/planyourvisit/placestogo.htm GOOD TO KNOW Parking – The parking areas in the national park site locations are free. Other sites in the recreation area may require a fee. National Park Service (NPS) parking lots are open from 8:00 AM to sunset. -

Fire Risk Is Up; Is Rattlesnake Risk Up, Too?

Fire Safety News Serving the communities of Castle Creek, Champagne Village, Deer Springs, West Lilac, Gordon Hill, Hidden Meadows, Jesmond Dene, Rimrock, and the Welk Resort A 501(c)(3) Community Service Organization SEPTEMBER 9, 2014 Ground forces move to the front in the battle against the 32,000-acre Eiler Fire, one of several fires to strike Northern California this summer. / Photo, Jeff Hall, CAL FIRE VIP Photographer Inside This Issue Forward this issue to a friend Parched Brush Intensifies Fire Risk Rattlesnakes Invading Deer Springs? Well, Maybe Not Drought Advice: Be Careful Out There Have you heard (or seen) ... Helpful Phone Numbers Parched Brush Intensifies Fire Risk As California firefighters chase blazes from the Oregon to the Mexico borders, fear grows that Southern California is on the verge of a catastrophic fire. San Diego County has already experienced an unprecedented event this year — Santa Ana wind-driven fires in the month of May. “Santa Ana winds have started many fires that historically have resulted in the loss of many lives and structures in San Diego County,” said CAL FIRE Battalion Chief Nick Schuler, who is based in Deer Springs. But the fires that struck North San Diego County in May struck with surprising ferocity. “This was the first time that we’ve seen a fire in a coastal community that moved so rapidly,” Schuler said of the Poinsettia Fire, which hit Carlsbad on May 14. “Within minutes of the fire breaking out, homes were threatened and self-evacuations were occurring. The magnitude of the fire was alarming.” Six hundred acres of tinder-dry brush burned in Carlsbad in a matter of hours, destroying five single-family residences, 18 apartment units and a large commercial building, and damaging other structures.