Download This Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEPI University Partnership Programme Anglia Ruskin University Arts University Bournemouth Bath Spa University BIMM (British &

HEPI University Partnership Programme Anglia Ruskin University Arts University Bournemouth Bath Spa University BIMM (British & Irish Modern Music Institute) Birkbeck, University of London Birmingham City University Bournemouth University Bradford College British Library Brunel University London Cardiff Metropolitan University Cardiff University City University London Coventry University De Montfort University Edge Hill University Edinburgh Napier University Glasgow Caledonian University gsm London Goldsmiths University of London Heriot-Watt University Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) ifs University College Imperial College London Keele University King’s College, London Kingston University Lancaster University Liverpool Hope University Liverpool John Moores University London School of Economics London South Bank University Loughborough University Middlesex University New College of the Humanities Northumbria University Norwich University of the Arts Nottingham Trent University Oxford Brookes University Peter Symonds College, Winchester Plymouth College of Art Plymouth University Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) Queen Mary University of London Queen’s University Belfast Regent’s University London Resource Development International (RDI) Ltd Royal Holloway University of London Royal Society of Chemistry Royal Veterinary College SOAS, University of London Sheffield Hallam University Staffordshire University Southampton Solent University The Academy of Contemporary Music The Institute of Contemporary Music Performance -

XIX.—Reginald, Bishop of Bath (Hjjfugi); His Episcopate, and His Share in the Building of the Church of Wells. by the Rev. C. M

XIX.—Reginald, bishop of Bath (HJJfUgi); his episcopate, and his share in the building of the church of Wells. By the Rev. C. M. CHURCH, M.A., F.8.A., Sub-dean and Canon Residentiary of Wells. Read June 10, 1886. I VENTURE to think that bishop Eeginald Fitzjocelin deserves a place of higher honour in the history of the diocese, and of the fabric of the church of Wells, than has hitherto been accorded to him. His memory has been obscured by the traditionary fame of bishop Robert as the "author," and of bishop Jocelin as the "finisher," of the church of Wells; and the importance of his episcopate as a connecting link in the work of these two master-builders has been comparatively overlooked. The only authorities followed for the history of his episcopate have been the work of the Canon of Wells, printed by Wharton, in his Anglia Sacra, 1691, and bishop Godwin, in his Catalogue of the Bishops of England, 1601—1616. But Wharton, in his notes to the text of his author, comments on the scanty notice of bishop Reginald ;a and Archer, our local chronicler, complains of the unworthy treatment bishop Reginald had received from Godwin, also a canon of his own cathedral church.b a Reginaldi gesta historicus noster brevius quam pro viri dignitate enarravit. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, i. 871. b Historicus noster et post eum Godwinus nimis breviter gesta Reginaldi perstringunt quae pro egregii viri dignitate narrationem magis applicatam de Canonicis istis Wellensibus merita sunt. Archer, Ghronicon Wellense, sive annales Ecclesiae Cathedralis Wellensis, p. -

Call for Immersion Fellows

Call for Immersion Fellows We are offering 24 paid fellowships to people from industry and academia to think deeply about the potential, challenges and opportunities in the realm of immersion. Fellowships run from September 2018 through to July 2019, but time commitment for Fellows will be significantly front-loaded to the period September to December 2018. Each Fellow will receive a £15k bursary to support time and research costs. The South West Creative Technology Network (SWCTN) is a £6.5 million project to expand the use of creative technologies across the region. The network will offer three one-year funded programmes around the themes of immersion, automation and data. The grant is part of Research England’s Connecting Capabilities Fund, which supports university collaboration and encourages commercialisation of products made through partnerships with industry. This new network is led by the University of the West of England (UWE Bristol), in partnership with Watershed in Bristol, Kaleider in Exeter, Bath Spa University, the University of Plymouth and Falmouth University. Photo by Max Mclure of REACT The Rooms festival Programme Over the next three years the partnership will recruit three cohorts of fellows. Each cohort will run for twelve months and focus on one of three challenge areas: immersion, automation and data. Fellows will be drawn from academia, industry and new talent. The cohort will engage in an initial period of three months deep thinking around the challenge area exploring what’s new, what’s good, where the gaps in the market are, what the challenges are, and what the potentials are. -

Memorial Inscriptions Bathwick LHS D-426

St Mary the Virgin, Bathwick – Smallcombe Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions Bathwick LHS Row P Names Inscriptions Notes D.P.25 Dorothy Harrison East: Bullock (1836-1914) In Loving Memory Edward Bullock of (1799-) DOROTHY HARRISON BULLOCK 2ND DAUGHTER OF Georgiana Sarah EDWARD BULLOCK ESQRE Bullock (1837-1922) SOME YEARS COMMON SERJEANT OF THE CITY OF LONDON FELL ASLEEP JANUARY 11TH 1914 Cross on 3 plinths. ―•― “HE GIVETH HIS BELOVED SLEEP.” In the 1851 census at 40 Woburn Square, Bloomsbury, London: Edward South: Bullock, aged 51 widower, Common Sergt of London, born at Spanish Also of Town, Jamaica, children: Catherine Elizth, aged 18, born at GEORGIANA Bloomsbury, Dorothy H, aged 14, born at Bloomsbury, and Georgiana, SARAH BULLOCK aged 13, born at Bloomsbury, a governess and three servants. YOUNGER DAUGHTER OF EDWARD BULLOCK ESQRE From The Edinburgh Gazette of Tue 27 Dec 1853 (No. 6346 p1033) FELL ASLEEP APRIL 16TH 1922. WHITEHALL, December 1, 1853. ― The Queen has been pleased to issue a new Commission of “O LORD IN THEE I HAVE TRUSTED.” Lieutenancy for the City of London, constituting and appointing the several persons under-mentioned to be Her Majesty’s Commissioners for that purpose, viz ... Edward Bullock, Esquire, Common Serjeant of Our City of London, and the Common Serjeant of Our said city for the time being; ... In Cambridge University Calendar for the Year 1857 in an advertisement for the English and Irish Church and University Assurance Society, 4, Trafalgar Square, Charing Cross, London on p 40 one of the trustees is: Edward Bullock, Esq., M.A., (Christ Church, Oxford), late Common Serjeant of London. -

BA (Hons) Architecture (Sept 2013)

Programme Specification BA (Hons) Textiles ARTS UNIVERSITY BOURNEMOUTH PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION The Programme Specification provides a summary of the main features of the BA (Hons) Textiles course, and the learning outcomes that a ‘typical’ student might reasonably be expected to achieve and demonstrate if he/she passes the course. Further detailed information on the learning outcomes, content and teaching and learning methods of each unit may be found in your Course Handbook. Key Course Information Final Award BA (Hons) Course Title Textiles Award Title BA (Hons) Textiles Teaching institution Arts University Bournemouth Awarding Institution Arts University Bournemouth Offered in the Faculty of: Art, Design and Architecture Contact details: Telephone number 01202 363354 Email [email protected] Professional accreditation None Length of course / mode of study 3 years full-time Level of final award (in FHEQ) Level 6 Subject benchmark statement Art and Design UCAS code W236 Language of study English ExternalExaminerforcourse ImeldaHughes Bath Spa University Please note that it is not appropriate for students to contact external examiners directly Date of Validation 2012 Date of most recent review N/A Date programme specification September 2012 written/revised Course Philosophy British textile design has a worldwide reputation for originality, creativity and innovation. At Arts University Bournemouth we will encourage you to fully embrace this long-standing tradition by providing the opportunity for you to become part of the next generation of distinctive, skilled and inventive designers and makers. Textiles at Arts University Bournemouth will provide you with the opportunity to become a creative textile designer/maker within this exciting and innovative global industry. -

Access Agreement 2018-19

FALMOUTH UNIVERSITY ACCESS AGREEMENT 2018-19 ACCESS AGREEMENT SUBMITTED TO THE OFFICE FOR FAIR ACCESS Submitted 25 April 2017; revised 22 June 2017 FALMOUTH UNIVERSITY ACCESS AGREEMENT 2018-19 Contents: 1. Introduction and OFFA priorities for 2018-19 page 3 2. Fees, student numbers and fee income page 5 3. Access, student success and progression measures page 7 4. Financial support page 15 5. Targets and milestones page 16 6. Monitoring and evaluation agreements page 16 7. Equality and Diversity page 16 8. Provision of information to prospective students page 17 9. Consulting with students page 17 Annex: Access Agreement Resource Plan, 2018-19 Page 2 of 18 1a. Introduction This Access Agreement sets out Falmouth University’s plans and targets to support access, student success and progression for the year 2018-19. This Agreement has been developed in the context of the University’s Strategic Plan for the period 2015 to 2020. The Strategic Plan’s key objectives reflect the University’s commitment to fair access across the student lifecycle. Our first objective is ‘to produce satisfied graduates who get great jobs’, which includes ambitious targets for student retention, student satisfaction and graduate employment. Our second objective is ‘to help grow Cornwall’, which includes a commitment to double the number of students recruited from the county from 2013-14 levels by 2020. This objective will be achieved through a sharpened focus on recruiting students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The Strategic Plan states: ‘We will work with other agencies in the region to build support systems to retain more of our creative talent for the benefit of Cornwall. -

Programme Specification

PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION BA (HONS) TEXTILES This Programme Specification is designed for prospective students, current students, graduates, academic staff and potential employers. It provides a summary of the main features of the programme and the intended learning outcomes that a typical student might reasonably be expected to achieve and demonstrate if he/she takes full advantage of the learning opportunities that are provided. Whilst every endeavour has been made to provide the course described in the Programme Specification, the University reserves the right to make such changes as may be appropriate for reasons of operational efficiency or due to circumstances beyond its control. Any changes are made in accordance with the University’s academic standards and quality procedures. This document is available in alternative formats on request. ARTS UNIVERSITY BOURNEMOUTH PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION The Programme Specification provides a summary of the main features of the BA (Hons) Textiles course, and the learning outcomes that a ‘typical’ student might reasonably be expected to achieve and demonstrate if he/she passes the course. Further detailed information on the learning outcomes, content and teaching and learning methods of each unit may be found within this Handbook and the online Unit Information, which is available on your course blog. Key Course Information Final Award BA (Hons) Course Title Textiles Award Title BA (Hons) Textiles Teaching institution Arts University Bournemouth Awarding Institution Arts University Bournemouth Offered -

Stanton Prior

STANTON PRIOR MEMORIAL INSCRIPTIONS 2017 Stanton Prior – Memorial Inscriptions Author: P J Bendall Date: 27-Oct-2017 Status: Issue 1 Issue 1 ii Stanton Prior – Memorial Inscriptions Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 Layout ............................................................................................................ 4 Churchyard ....................................................................................................... 5 Missing Inscriptions ........................................................................................... 38 Internal Memorials ............................................................................................ 40 Plaques ................................................................................................... 40 Ledger Stones ........................................................................................... 43 Windows ................................................................................................. 44 Index ............................................................................................................ 48 Issue 1 iii Stanton Prior – Memorial Inscriptions Issue 1 iv Stanton Prior – Memorial Inscriptions Introduction restored. At morning service there was a celebration of all who had helped in any way, and especially to thank the Holy Communion, the sermon being preached by the God that this good work had been brought to a successful Rector, -

National Archdeacons' Forum Mailing

NATIONAL ARCHDEACONS’ FORUM serving the Church of England and the Church in Wales Archdeacons’ News Bulletin no. 27 September 2017 from Norman Boakes Archdeacons’ National Executive Officer Having faith is all about having faith. I know that is a truism, but recent events have reminded us of its truth. Confronted by terrorist violence in Spain and Finland, and witnessing some of the hatred and fear in the violence at Charlottesville, it is all too easy for us to react and withdraw into ourselves. But the way of Jesus is always to go on in faith as he did, trusting in God, and learning to trust more deeply in God as we live with uncertainty, and struggle to understand and to engage with the world around us. The path of love is the only way which leads to fullness of life and true peace. As so many things begin again with the arrival of autumn days, and as so much challenges us, may we grow in faith. With best wishes and prayers, Norman [email protected] 023 8076 7735 * * * * * Archdeacons’ Training Events Bookings for all of the events below have been slow. If you wish to come, please book immediately, so we can assess whether each of these events is needed or should be cancelled. Church House Event for Archdeacons There will be another event entitled A Day at Church House on Thursday 5th October 2017. As before the aim of this day is to offer an opportunity for those archdeacons who are interested to receive briefings and updates from those with whom they most work, and to be able to ask questions and raise issues with them. -

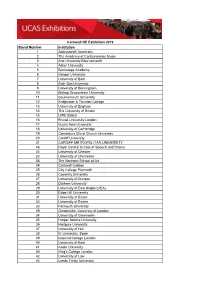

Stand Number Institution 1 Aberystwyth University 2 the Academy of Contemporary Music 3 Arts University Bournemouth 4 Aston Univ

Cornwall HE Exhibition 2019 Stand Number Institution 1 Aberystwyth University 2 The Academy of Contemporary Music 3 Arts University Bournemouth 4 Aston University 5 Backstage Academy 6 Bangor University 7 University of Bath 8 Bath Spa University 9 University of Birmingham 10 Bishop Grosseteste University 11 Bournemouth University 12 Bridgwater & Taunton College 13 University of Brighton 14 The University of Bristol 15 UWE Bristol 16 Brunel University London 17 Bucks New University 18 University of Cambridge 19 Canterbury Christ Church University 20 Cardiff University 21 CARDIFF METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY 48 Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 22 University of Chester 23 University of Chichester 58 The Northern School of Art 24 Cornwall College 25 City College Plymouth 26 Coventry University 27 University of Dundee 28 Durham University 29 University of East Anglia (UEA) 30 Edge Hill University 31 University of Essex 32 University of Exeter 33 Falmouth University 49 Goldsmiths, University of London 34 University of Greenwich 35 Harper Adams University 36 Hartpury University 37 University of Hull 38 IE University, Spain 39 Imperial College London 40 University of Kent 41 Keele University 50 King's College London 42 University of Law 43 Leeds Trinity University 44 University of Leicester 45 University of Liverpool 46 Liverpool Hope University 47 Liverpool John Moores University 54 London Metropolitan University 51 London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) 55 London South Bank University 56 Loughborough University 57 The University -

Access and Participation Plan 2019-20

Bath Spa University 2019-20 access and participation plan Assessment of current performance The following summary of the assessment of the University’s current performance in access, retention and attainment of underrepresented groups is based on the analysis of internal data, University and College Admissions Service (UCAS) End of Cycle data, absolute and relative performance in Higher Education Statistical Agency (HESA) widening participation UK performance indicator data and Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) metrics for undergraduate students, and the Post Graduate Certificate in Education Initial Teacher Training (PGCE ITT) trainee number census for groups currently underrepresented in the teaching profession. The assessment of performance in student progression is based on an analysis of HESA Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education Survey (DLHE) data and PGCE ITT destination data. For all measures based on 2016/17 or 2015/16 HESA performance indicator data, the university performed at sector average. The analysis is summarised in Table 1. Overview Access Between 2012 and 2017 the university’s offer rate for June deadline applications (all ages) increased from 62.8% to 83.4% and for young applications from 70.2% to 87.8%.1 The gender gap in offer rate for male and female all age applicants narrowed from -8.9 percentage points in 2012 to +0.5 of a percentage point in 2017, and for young male and female applicants narrowed from -7.2 percentage points in 2012 to +0.9 of a percentage point in 2017.1 Internal analysis of 2016/17 undergraduate registration data showed that 44% were classified as from NS-SEC 4-8 occupational backgrounds and, where disclosed, 32% came from backgrounds where there was no parental experience of higher education. -

College and University Acceptances

COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY ACCEPTANCES 2016 -2020 UNITED KINGDOM • University of Bristol • High Point University • Aberystwyth University • University of Cardiff • Hofstra University • Arts University Bournemouth • University of Central Lancashire • Ithaca College • Aston University • University of East Anglia • Lesley University • Bath Spa University • University of East London • Long Island University - CW Post • Birkbeck University of London • University of Dundee • Loyola Marymount University • Bornemouth University • University of Edinburgh • Loyola University Chicago • Bristol, UWE • University of Essex • Loyola University Maryland • Brunel University London • University of Exeter • Lynn University • Cardiff University • University of Glasgow • Marist College • City and Guilds of London Art School • University of Gloucestershire • McGill University • City University of London • University of Greenwich • Miami University • Durham University • University of Kent • Michigan State University • Goldsmiths, University of London • University of Lancaster • Missouri Western State University • Greenwich School of Management • University of Leeds • New York Institute of Technology • Keele University • University of Lincoln • New York University • King’s College London • University of Liverpool • Northeastern University • Imperial College London • University of Loughborough • Oxford College of Emory University • Imperial College London - Faculty of Medicine • University of Manchester • Pennsylvania State University • International School for Screen