Living Structure Down to Earth and up to Heaven: Christopher Alexander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neuroscience, the Natural Environment, and Building Design

Neuroscience, the Natural Environment, and Building Design. Nikos A. Salingaros, Professor of Mathematics, University of Texas at San Antonio. Kenneth G. Masden II, Associate Professor of Architecture, University of Texas at San Antonio. Presented at the Bringing Buildings to Life Conference, Yale University, 10-12 May 2006. Chapter 5 of: Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life, edited by Stephen R. Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador (John Wiley, New York, 2008), pages 59-83. Abstract: The human mind is split between genetically-structured neural systems, and an internally-generated worldview. This split occurs in a way that can elicit contradictory mental processes for our actions, and the interpretation of our environment. Part of our perceptive system looks for information, whereas another part looks for meaning, and in so doing gives rise to cultural, philosophical, and ideological constructs. Architects have come to operate in this second domain almost exclusively, effectively neglecting the first domain. By imposing an artificial meaning on the built environment, contemporary architects contradict physical and natural processes, and thus create buildings and cities that are inhuman in their form, scale, and construction. A new effort has to be made to reconnect human beings to the buildings and places they inhabit. Biophilic design, as one of the most recent and viable reconnection theories, incorporates organic life into the built environment in an essential manner. Extending this logic, the building forms, articulations, and textures could themselves follow the same geometry found in all living forms. Empirical evidence confirms that designs which connect humans to the lived experience enhance our overall sense of wellbeing, with positive and therapeutic consequences on physiology. -

Open Source Architecture, Began in Much the Same Way As the Domus Article

About the Authors Carlo Ratti is an architect and engineer by training. He practices in Italy and teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he directs the Senseable City Lab. His work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale and MoMA in New York. Two of his projects were hailed by Time Magazine as ‘Best Invention of the Year’. He has been included in Blueprint Magazine’s ‘25 People who will Change the World of Design’ and Wired’s ‘Smart List 2012: 50 people who will change the world’. Matthew Claudel is a researcher at MIT’s Senseable City Lab. He studied architecture at Yale University, where he was awarded the 2013 Sudler Prize, Yale’s highest award for the arts. He has taught at MIT, is on the curatorial board of the Media Architecture Biennale, is an active protagonist of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s 89plus, and has presented widely as a critic, speaker, and artist in-residence. Adjunct Editors The authorship of this book was a collective endeavor. The text was developed by a team of contributing editors from the worlds of art, architecture, literature, and theory. Assaf Biderman Michele Bonino Ricky Burdett Pierre-Alain Croset Keller Easterling Giuliano da Empoli Joseph Grima N. John Habraken Alex Haw Hans Ulrich Obrist Alastair Parvin Ethel Baraona Pohl Tamar Shafrir Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: The Elements of Modern Architecture The New Autonomous House World Architecture: The Masterworks Mediterranean Modern See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com Contents -

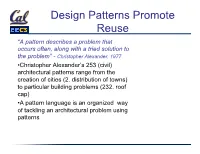

Design Patterns Promote Reuse

Design Patterns Promote Reuse “A pattern describes a problem that occurs often, along with a tried solution to the problem” - Christopher Alexander, 1977 • Christopher Alexander’s 253 (civil) architectural patterns range from the creation of cities (2. distribution of towns) to particular building problems (232. roof cap) • A pattern language is an organized way of tackling an architectural problem using patterns Kinds of Patterns in Software • Architectural (“macroscale”) patterns • Model-view-controller • Pipe & Filter (e.g. compiler, Unix pipeline) • Event-based (e.g. interactive game) • Layering (e.g. SaaS technology stack) • Computation patterns • Fast Fourier transform • Structured & unstructured grids • Dense linear algebra • Sparse linear algebra • GoF (Gang of Four) Patterns: structural, creational, behavior The Gang of Four (GoF) • 23 structural design patterns • description of communicating objects & classes • captures common (and successful) solution to a category of related problem instances • can be customized to solve a specific (new) problem in that category • Pattern ≠ • individual classes or libraries (list, hash, ...) • full design—more like a blueprint for a design The GoF Pattern Zoo 1. Factory 13. Observer 14. Mediator 2. Abstract factory 15. Chain of responsibility 3. Builder Creation 16. Command 4. Prototype 17. Interpreter 18. Iterator 5. Singleton/Null obj 19. Memento (memoization) 6. Adapter Behavioral 20. State 21. Strategy 7. Composite 22. Template 8. Proxy 23. Visitor Structural 9. Bridge 10. Flyweight 11. -

The Origins of Pattern Theory: the Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World

www.computer.org/software The Origins of Pattern Theory: The Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World Christopher Alexander Vol. 16, No. 5 September/October 1999 This material is presented to ensure timely dissemination of scholarly and technical work. Copyright and all rights therein are retained by authors or by other copyright holders. All persons copying this information are expected to adhere to the terms and constraints invoked by each author's copyright. In most cases, these works may not be reposted without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. © 2006 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. For more information, please see www.ieee.org/portal/pages/about/documentation/copyright/polilink.html. THE ORIGINS OF PATTERN THEORY THE FUTURE OF THE THEORY, AND THE GENERATION OF A LIVING WORLD Christopher Alexander Introduction by James O. Coplien nce in a great while, a great idea makes it across the boundary of one discipline to take root in another. The adoption of Christopher O Alexander’s patterns by the software community is one such event. Alexander both commands respect and inspires controversy in his own discipline; he is the author of several books with long-running publication records, the first recipient of the AIA Gold Medal for Research, a member of the Swedish Royal Academy since 1980, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, recipient of dozens of awards and honors including the Best Building in Japan award in 1985, and the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Distinguished Professor Award. -

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology Pattern Language, 1977 Network of Relationships “We need a web way of thinking.” - Jane Jacobs Herbert Simon, 1962 “The Architecture of Complexity” - nearly decomposable hierarchies (with “panarchic” connections - Holling) Christopher Alexander, 1964-5 “A city is not a tree” – its “overlaps” create clusters, or “patterns,” that can be manipulated more easily (related to Object-Oriented Programming) The surprising existing benefits of Pattern Language technology.... * “Design patterns” used as a widespread computer programming system (Mac OS, iPhone, most games, etc.) * Wiki invented by Ward Cunningham as a direct outgrowth * Direct lineage to Agile, Scrum, Extreme Programming * Pattern languages used in many other fields …. So why have they not been more infuential in the built environment??? Why have pattern languages not been more infuential in the built environment?.... * Theory 1: “Architects are just weird!” (Preference for “starchitecure,” extravagant objects, etc.) * Theory 2: The original book is too “proprietary,” not “open source” enough for extensive development and refinement * Theory 3: The software people, especially, used key strategies to make pattern languages far more useful, leading to an explosion of useful new tools and approaches …. So what can we learn from them??? * Portland, OR. Based NGO with international network of researchers * Executive director is Michael Mehaffy, student and long-time colleague of Christopher Alexander, inter-disciplinary collaborator in philosophy, sciences, public affairs, business and economics, architecture, planning * Board member is Ward Cunningham, one of the pioneers of pattern languages in software, Agile, Scrum etc., and inventor of wiki * Other board members are architects, financial experts, former students of Alexander Custom “Project Pattern Languages” (in conventional paper format) Custom “Project Pattern Languages” create the elements of a “generative code” (e.g. -

The Origins of Pattern Theory the Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World

THE ORIGINS OF PATTERN THEORY THE FUTURE OF THE THEORY, AND THE GENERATION OF A LIVING WORLD Christopher Alexander Introduction by James O. Coplien nce in a great while, a great idea makes it across the boundary of one discipline to take root in another. The adoption of Christopher O Alexander’s patterns by the software community is one such event. Alexander both commands respect and inspires controversy in his own discipline; he is the author of several books with long-running publication records, the first recipient of the AIA Gold Medal for Research, a member of the Swedish Royal Academy since 1980, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, recipient of dozens of awards and honors including the Best Building in Japan award in 1985, and the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Distinguished Professor Award. It is odd that his ideas should have found a home in software, a discipline that deals not with timbers and tiles but with pure thought stuff, and with ephemeral and weightless products called programs. The software community embraced the pattern vision for its relevance to problems that had long plagued software design in general and object-oriented design in particular. September/October 1999 IEEE Software 71 Focusing on objects had caused us to lose the pattern discipline that the software community has system perspective. Preoccupation with design yet scarcely touched: the moral imperative to build method had caused us to lose the human perspec- whole systems that contribute powerfully to the tive. The curious parallels between Alexander’s quality of life, as we recognize and rise to the re- world of buildings and our world of software con- sponsibility that accompanies our position of influ- struction helped the ideas to take root and thrive in ence in the world. -

Assessing Alexander's Later Contributions to a Science of Cities

Review Assessing Alexander’s Later Contributions to a Science of Cities Michael W. Mehaffy KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 114 28 Stockholm, Sweden; mmehaff[email protected] or michael.mehaff[email protected] Received: 23 April 2019; Accepted: 28 May 2019; Published: 30 May 2019 Abstract: Christopher Alexander published his longest and arguably most philosophical work, The Nature of Order, beginning in 2003. Early criticism assessed that text to be a speculative failure; at best, unrelated to Alexander’s earlier, mathematically grounded work. On the contrary, this review presents evidence that the newer work was a logically consistent culmination of a lifelong and remarkably useful inquiry into part-whole relations—an ancient but still-relevant and even urgent topic of design, architecture, urbanism, and science. Further evidence demonstrates that Alexander’s practical contributions are remarkably prodigious beyond architecture, in fields as diverse as computer science, biology and organization theory, and that these contributions continue today. This review assesses the potential for more particular contributions to the urban professions from the later work, and specifically, to an emerging “science of cities.” It examines the practical, as well as philosophical contributions of Alexander’s proposed tools and methodologies for the design process, considering both their quantitative and qualitative aspects, and their potential compatibility with other tools and strategies now emerging from the science of cities. Finally, it highlights Alexander’s challenge to an architecture profession that seems increasingly isolated, mired in abstraction, and incapable of effectively responding to larger technological and philosophical challenges. Keywords: Christopher Alexander; The Nature of Order; pattern language; structure-preserving transformations; science of cities 1. -

Interview: the Battle for Ordinary Human Existence in Our Time

The Battle for Ordinary Human Existence in Our Time Upon the completion of his four-volume work, The Nature of Order, Christopher Alexander talks with Traditional Building about his vision for our future architecture. Christopher Alexander interviewed by Kim A. O’Connell In the 1970s, architect Christopher Alexander, along with his colleagues at the Center for Environmental Structure in Berkeley, California, published a trilogy of books—The Timeless Way of Building, A Pattern Language, and The Oregon Experiment—centered on the theory that people can and should take back the design and construction of their towns and cities. By distilling natural patterns into an understandable grammar for the built environment, Alexander advanced the belief that, in building something, one could “also repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent, and more whole.” Three decades later, Alexander has expanded on the concept of wholeness in The Nature of Order, a four-volume opus in which he presents an organic approach to architectural theory and practice. Instead of subscribing to the artificially rigid constraints of current construction—a typically linear progression from architect to builder to subcontractor, with often banal or outlandish results—Alexander proposes a humanistic, scientific, and artistic methodology, in which buildings and towns are created through a natural, unfolding, living process. His work celebrates traditional buildings, not out of superficial nostalgia for historic styles or details, but because they are often the best examples we have of such holistic process at work, and are therefore highly instructive for a future- oriented profession that has, in Alexander’s view, largely lost its way. -

T He G Enerative M Aster P Lan F Or H Arbor Hi

T H E B R O O K I N G S P L A N T H E G E N E R A T I V E M A S T E R P L A N F O R H A R B O R H I L L S N E A R B R O O K I N G S O R E G O N A M O D E L C R E A T I O N P R O C E S S F O R 2 1 S T - C E N T U R Y C I T I E S THE BROOKINGS PLAN COLOR View of the Pacific ocean, from Harbor Peak, looking south 2 THE GENERATIVE MASTER PLAN FOR THE NEW TOWN OF HARBOR HILLS, BROOKINGS, OREGON Submitted jointly to The Commissioners of Curry County and to The City Council of Brookings, Oregon Christopher Alexander Randall Schmidt with thanks to our client and contributor Bill Buchanan for help, discussion, en- couragment, and many, much-needed insights and corrections First Edition, January 2005 (Part One only) subject to correction The Center for Environmental Structure & PatternLanguage.com Berkeley, California 3 THE BROOKINGS PLAN DRAFT VERSION the center for environmental structure berkeley california in association with patternlanguage.com © 2005 christopher alexander previous versions © 2003 © 2004 christopher alexander Published by Center for Environmental Structure Publishing 2701 Shasta Road, Berkeley, California 94708 CESP is a trademark of the Center for Environmental Structure. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Center for Environmental Structure. -

The Patterns of Architecture/T3xture

THE PATTERNS OF ARCHITECTURE NIKOS A. SALINGAROS Published in Lynda Burke, Randy Sovich, and Craig Purcell, Editors: T3XTURE No. 3, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016, pages 7-24. EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION Pattern theory has not as yet transformed architectural practice—despite the acclaim for A Pattern Language, 1 Christopher Alexander’s book, which introduced and substantiated the theory. However, it has generated a great amount of far-ranging, supportive scholarship. In this essay Nikos Salingaros expands the scope of the pattern types under consideration, and explicates some of the mathematical, scientific and humanistic justification for the pattern approach. The author also argues for the manifest superiority of the pattern approach to design over Modernist and contemporary theories of the last one hundred years. To a great extent Dr. Salingaros’s conviction rests on the process and goals of the pattern language method which have as their basis the fundamental realities of the natural world: the mathematics of nature (many that have been studied since the beginning of human history); the process of organic development; and the ideal structural environment for human activity. For Salingaros, Alexander, et al. aesthetics in Architecture derive from these principles rather than from notions of style or artistic inspiration. AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION — KEY PATTERN CONCEPTS Pattern. A pattern is a discovered organization of space, and also a coherent merging of geometry with human actions. In common usage “pattern” has an expansive definition. In Architecture “pattern” often equates with “solution”. In any discussion of architectural pattern theory the word “pattern” itself is used repeatedly, often with reference to somewhat different concepts. -

Patterns, Process and Systems-Thinking: Putting Social Pattern Languages to Work Justin Smith Washington State University and the Public Sphere Project

Patterns, Process and Systems-Thinking: Putting Social Pattern Languages to Work Justin Smith Washington State University and The Public Sphere Project ABSTRACT Following a 2006 study aimed at evaluating the validity of pattern languages within the context of civic communication and social change, a number of insights emerged connected to the field of system dynamics and the practice of process monitoring. The study revealed that both system dynamics and process monitoring provide a number of opportunities for further grounding pattern thinking, as well as in supporting adaptive approaches to pattern based capacity building among community networks. Based upon these initial findings it would appear that further investigation is necessary to better understand how patterns, systems and process can be integrated for ever more effective planning and capacity building among civil society, community networks and social change advocates. KEYWORDS: Pattern Languages, System Dynamics, Process Monitoring, Community Networks Patterns and Systems In 2006 a study of the Liberating Voices project was carried out, which aimed at evaluating the validity of pattern languages within the context of civic communication and social change. Following from Christopher Alexander’s conception of design patterns (1977; 1979), the Liberating Voices project has been an attempt to utilize Alexander’s model for constructing effective civic communicative systems (Schuler, 2002). And just as Alexander envisioned multiple applications for designing buildings and towns, the Liberating Voices project perceives patterns as useful constructs for community empowerment, as well as supportive for an overall re-conceptualization of the ways in which communities and a networked civil society think and engage in social change (Schuler, 2001; Smith, 2007). -

Design Patterns Attribution

Software Engineering I cs361 Announcements ✖ Friday Extra office hour of “Coding Lab” 2-3pm ✖ CI instructions added to Assignment 3 ✖ travis-ci.ORG ✖http://www.umlet.com/ umletino/umletino.html Design Patterns Attribution Much of this material inspired by a great slides from Kenneth M. Anderson, available here: https://www.cs.colorado.edu/~kena/ classes/5448/f12/lectures/07- designpatterns.pdf Also, here: https://sourcemaking.com/ design_patterns/template_method Christopher Alexander ✖ Worked as in computer science but trained as an architect ✖ Wrote a book called A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. ✖ Adopted as some cities as a building code The timeless Way of Building ✖Asks the question, “is quality objective?” ✖Specifically, “What makes us know when an architectural design is good? Is there an objective basis for such a judgement?” Approach He studied the problem of identifying what makes a good architectural design by observing: • buildings, • towns, • streets, • homes, • community centers, • etc. When he found a good example, he would compare with others. Four Elements of a Pattern Alexander identified four elements to describe a pattern: • The name of the pattern • The purpose of the pattern: what problem it solves • How to solve the problem • The constraints we have to consider in our solution Inspired by Alexanders Work Christopher Alexander Inspired by Alexanders Work Christopher Alexander Inspired by Alexanders Work https://archive.org/details/msdos_SimCity_1989 Inspired by Alexanders Work Software design patterns