Restoring Function and Form to Patterns: DCI As Agile's Expression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patterns Senior Member of Technical Staff and Pattern Languages Knowledge Systems Corp

Kyle Brown An Introduction to Patterns Senior Member of Technical Staff and Pattern Languages Knowledge Systems Corp. 4001 Weston Parkway CSC591O Cary, North Carolina 27513-2303 April 7-9, 1997 919-481-4000 Raleigh, NC [email protected] http://www.ksccary.com Copyright (C) 1996, Kyle Brown, Bobby Woolf, and 1 2 Knowledge Systems Corp. All rights reserved. Overview Bobby Woolf Senior Member of Technical Staff O Patterns Knowledge Systems Corp. O Software Patterns 4001 Weston Parkway O Design Patterns Cary, North Carolina 27513-2303 O Architectural Patterns 919-481-4000 O Pattern Catalogs [email protected] O Pattern Languages http://www.ksccary.com 3 4 Patterns -- Why? Patterns -- Why? !@#$ O Learning software development is hard » Lots of new concepts O Must be some way to » Hard to distinguish good communicate better ideas from bad ones » Allow us to concentrate O Languages and on the problem frameworks are very O Patterns can provide the complex answer » Too much to explain » Much of their structure is incidental to our problem 5 6 Patterns -- What? Patterns -- Parts O Patterns are made up of four main parts O What is a pattern? » Title -- the name of the pattern » A solution to a problem in a context » Problem -- a statement of what the pattern solves » A structured way of representing design » Context -- a discussion of the constraints and information in prose and diagrams forces on the problem »A way of communicating design information from an expert to a novice » Solution -- a description of how to solve the problem » Generative: -

Neuroscience, the Natural Environment, and Building Design

Neuroscience, the Natural Environment, and Building Design. Nikos A. Salingaros, Professor of Mathematics, University of Texas at San Antonio. Kenneth G. Masden II, Associate Professor of Architecture, University of Texas at San Antonio. Presented at the Bringing Buildings to Life Conference, Yale University, 10-12 May 2006. Chapter 5 of: Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life, edited by Stephen R. Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador (John Wiley, New York, 2008), pages 59-83. Abstract: The human mind is split between genetically-structured neural systems, and an internally-generated worldview. This split occurs in a way that can elicit contradictory mental processes for our actions, and the interpretation of our environment. Part of our perceptive system looks for information, whereas another part looks for meaning, and in so doing gives rise to cultural, philosophical, and ideological constructs. Architects have come to operate in this second domain almost exclusively, effectively neglecting the first domain. By imposing an artificial meaning on the built environment, contemporary architects contradict physical and natural processes, and thus create buildings and cities that are inhuman in their form, scale, and construction. A new effort has to be made to reconnect human beings to the buildings and places they inhabit. Biophilic design, as one of the most recent and viable reconnection theories, incorporates organic life into the built environment in an essential manner. Extending this logic, the building forms, articulations, and textures could themselves follow the same geometry found in all living forms. Empirical evidence confirms that designs which connect humans to the lived experience enhance our overall sense of wellbeing, with positive and therapeutic consequences on physiology. -

Open Source Architecture, Began in Much the Same Way As the Domus Article

About the Authors Carlo Ratti is an architect and engineer by training. He practices in Italy and teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he directs the Senseable City Lab. His work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale and MoMA in New York. Two of his projects were hailed by Time Magazine as ‘Best Invention of the Year’. He has been included in Blueprint Magazine’s ‘25 People who will Change the World of Design’ and Wired’s ‘Smart List 2012: 50 people who will change the world’. Matthew Claudel is a researcher at MIT’s Senseable City Lab. He studied architecture at Yale University, where he was awarded the 2013 Sudler Prize, Yale’s highest award for the arts. He has taught at MIT, is on the curatorial board of the Media Architecture Biennale, is an active protagonist of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s 89plus, and has presented widely as a critic, speaker, and artist in-residence. Adjunct Editors The authorship of this book was a collective endeavor. The text was developed by a team of contributing editors from the worlds of art, architecture, literature, and theory. Assaf Biderman Michele Bonino Ricky Burdett Pierre-Alain Croset Keller Easterling Giuliano da Empoli Joseph Grima N. John Habraken Alex Haw Hans Ulrich Obrist Alastair Parvin Ethel Baraona Pohl Tamar Shafrir Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: The Elements of Modern Architecture The New Autonomous House World Architecture: The Masterworks Mediterranean Modern See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com Contents -

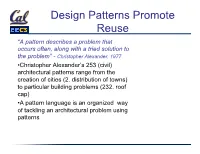

Design Patterns Promote Reuse

Design Patterns Promote Reuse “A pattern describes a problem that occurs often, along with a tried solution to the problem” - Christopher Alexander, 1977 • Christopher Alexander’s 253 (civil) architectural patterns range from the creation of cities (2. distribution of towns) to particular building problems (232. roof cap) • A pattern language is an organized way of tackling an architectural problem using patterns Kinds of Patterns in Software • Architectural (“macroscale”) patterns • Model-view-controller • Pipe & Filter (e.g. compiler, Unix pipeline) • Event-based (e.g. interactive game) • Layering (e.g. SaaS technology stack) • Computation patterns • Fast Fourier transform • Structured & unstructured grids • Dense linear algebra • Sparse linear algebra • GoF (Gang of Four) Patterns: structural, creational, behavior The Gang of Four (GoF) • 23 structural design patterns • description of communicating objects & classes • captures common (and successful) solution to a category of related problem instances • can be customized to solve a specific (new) problem in that category • Pattern ≠ • individual classes or libraries (list, hash, ...) • full design—more like a blueprint for a design The GoF Pattern Zoo 1. Factory 13. Observer 14. Mediator 2. Abstract factory 15. Chain of responsibility 3. Builder Creation 16. Command 4. Prototype 17. Interpreter 18. Iterator 5. Singleton/Null obj 19. Memento (memoization) 6. Adapter Behavioral 20. State 21. Strategy 7. Composite 22. Template 8. Proxy 23. Visitor Structural 9. Bridge 10. Flyweight 11. -

The Culture of Patterns

UDC 681.3.06 The Culture of Patterns James O. Coplien Vloebergh Professor of Computer Science, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, PO Box 4557, Wheaton, IL 60189-4557 USA [email protected] Abstract. The pattern community came about from a consciously crafted culture, a culture that has persisted, grown, and arguably thrived for a decade. The culture was built on a small number of explicit principles. The culture became embodied in its activities conferences called PLoPs that centered on a social activity for reviewing technical worksand in a body of literature that has wielded broad influence on software design. Embedded within the larger culture of software development, the pattern culture has enjoyed broad influence on software development worldwide. The culture hasnt been without its problems: conflict with academic culture, accusations of cultism, and compromises with other cultures. However, its culturally rich principles still live on both in the original organs of the pattern community and in the activities of many other software communities worldwide. 1. Introduction One doesnt read many papers on culture in the software literature. You might ask why anyone in software would think that culture is important enough that an article about culture would appear in such a journal, and you might even ask yourself: just what is culture, anyhow? The software pattern community has long taken culture as a primary concern and focus. Astute observers of the pattern community note a cultural tone to the conferences and literature of the discipline, but probably view it as a distant and puzzling phenomenon. Casual users of the pattern form may not even be aware of the cultural focus or, if they are, may discount it as a distraction. -

A Model of Inheritance for Declarative Visual Programming Languages

An Abstract Of The Dissertation Of Rebecca Djang for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science presented on December 17, 1998. Title: Similarity Inheritance: A Model of Inheritance for Declarative Visual Programming Languages. Abstract approved: Margaret M. Burnett Declarative visual programming languages (VPLs), including spreadsheets, make up a large portion of both research and commercial VPLs. Spreadsheets in particular enjoy a wide audience, including end users. Unfortunately, spreadsheets and most other declarative VPLs still suffer from some of the problems that have been solved in other languages, such as ad-hoc (cut-and-paste) reuse of code which has been remedied in object-oriented languages, for example, through the code-reuse mechanism of inheritance. We believe spreadsheets and other declarative VPLs can benefit from the addition of an inheritance-like mechanism for fine-grained code reuse. This dissertation first examines the opportunities for supporting reuse inherent in declarative VPLs, and then introduces similarity inheritance and describes a prototype of this model in the research spreadsheet language Forms/3. Similarity inheritance is very flexible, allowing multiple granularities of code sharing and even mutual inheritance; it includes explicit representations of inherited code and all sharing relationships, and it subsumes the current spreadsheet mechanisms for formula propagation, providing a gradual migration from simple formula reuse to more sophisticated uses of inheritance among objects. Since the inheritance model separates inheritance from types, we investigate what notion of types is appropriate to support reuse of functions on different types (operation polymorphism). Because it is important to us that immediate feedback, which is characteristic of many VPLs, be preserved, including feedback with respect to type errors, we introduce a model of types suitable for static type inference in the presence of operation polymorphism with similarity inheritance. -

Pedagogical and Elementary Patterns Patterns Overview

Pedagogical and Elementary Patterns Overview Patterns Joe Bergin Pace University http://csis.pace.edu/~bergin Thanks to Eugene Wallingford for some material here. Jim (Cope) Coplien also gave advice in the design. 11/26/00 1 11/26/00 2 Patterns--What they DO Where Patterns Came From • Capture Expert Practice • Christopher Alexander --A Pattern Language • Communicate Expertise to Others – Architecture • Solve Common Recurring Problems • Structural Relationships that recur in good spaces • Ward Cunningham, Kent Beck (oopsla ‘87), • Vocabulary of Solutions. Dick Gabriel, Jim Coplien, and others • Bring a set of forces/constraints into • Johnson, Gamma, Helm, and Vlisides (GOF) equilibrium • Structural Relationships that recur in good programs • Work with other patterns 11/26/00 3 11/26/00 4 Patterns Branch Out Patterns--What they ARE • Software Design Patterns (GOF...) •A Thing • Organizational Patterns (XP, SCRUM...) • A Description of a Thing • Telecommunication Patterns (Hub…) • A Description of how to Create the Thing • Pedagogical Patterns •A Solution of a Recurring Problem in a • Elementary Patterns Context – Unfortunately this “definition” is only useful if you already know what patterns are 11/26/00 5 11/26/00 6 Patterns--What they ARE (2) Elements of a Pattern • Structural relationships between •Problem components of a system that brings into • Context equilibrium a set of demands on the system •Forces • A way to generate complex (emergent) •Solution behavior from simple rules • Examples of Use (several) • A way to make the world a better place for humans -- not just developers or teachers... • Consequences and Resulting Context 11/26/00 7 11/26/00 8 Exercise Exercise • Problem: Build a stairway up a castle tower • Problem: Design the intersection of two or • Context: 12th Century Denmark. -

The Origins of Pattern Theory: the Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World

www.computer.org/software The Origins of Pattern Theory: The Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World Christopher Alexander Vol. 16, No. 5 September/October 1999 This material is presented to ensure timely dissemination of scholarly and technical work. Copyright and all rights therein are retained by authors or by other copyright holders. All persons copying this information are expected to adhere to the terms and constraints invoked by each author's copyright. In most cases, these works may not be reposted without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. © 2006 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. For more information, please see www.ieee.org/portal/pages/about/documentation/copyright/polilink.html. THE ORIGINS OF PATTERN THEORY THE FUTURE OF THE THEORY, AND THE GENERATION OF A LIVING WORLD Christopher Alexander Introduction by James O. Coplien nce in a great while, a great idea makes it across the boundary of one discipline to take root in another. The adoption of Christopher O Alexander’s patterns by the software community is one such event. Alexander both commands respect and inspires controversy in his own discipline; he is the author of several books with long-running publication records, the first recipient of the AIA Gold Medal for Research, a member of the Swedish Royal Academy since 1980, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, recipient of dozens of awards and honors including the Best Building in Japan award in 1985, and the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Distinguished Professor Award. -

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology Pattern Language, 1977 Network of Relationships “We need a web way of thinking.” - Jane Jacobs Herbert Simon, 1962 “The Architecture of Complexity” - nearly decomposable hierarchies (with “panarchic” connections - Holling) Christopher Alexander, 1964-5 “A city is not a tree” – its “overlaps” create clusters, or “patterns,” that can be manipulated more easily (related to Object-Oriented Programming) The surprising existing benefits of Pattern Language technology.... * “Design patterns” used as a widespread computer programming system (Mac OS, iPhone, most games, etc.) * Wiki invented by Ward Cunningham as a direct outgrowth * Direct lineage to Agile, Scrum, Extreme Programming * Pattern languages used in many other fields …. So why have they not been more infuential in the built environment??? Why have pattern languages not been more infuential in the built environment?.... * Theory 1: “Architects are just weird!” (Preference for “starchitecure,” extravagant objects, etc.) * Theory 2: The original book is too “proprietary,” not “open source” enough for extensive development and refinement * Theory 3: The software people, especially, used key strategies to make pattern languages far more useful, leading to an explosion of useful new tools and approaches …. So what can we learn from them??? * Portland, OR. Based NGO with international network of researchers * Executive director is Michael Mehaffy, student and long-time colleague of Christopher Alexander, inter-disciplinary collaborator in philosophy, sciences, public affairs, business and economics, architecture, planning * Board member is Ward Cunningham, one of the pioneers of pattern languages in software, Agile, Scrum etc., and inventor of wiki * Other board members are architects, financial experts, former students of Alexander Custom “Project Pattern Languages” (in conventional paper format) Custom “Project Pattern Languages” create the elements of a “generative code” (e.g. -

Lean Architecture for Agile Software Development

LEAN ARCHITECTURE FOR AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT This manuscript is Copyright ©2009 by James O. Coplien and Gertrud Bjørnvig. All rights reserved. No portion of this manuscript may be copied or repro- duced in any form nor by any means, whether elec- tronic, reprographic, or photographic, without prior written consent of the authors and all pertinent legal stakeholders. For a printable copy of this draft, contact Jim Co- plien at [email protected] Draft of August 2, 2009 ii LEAN ARCHITECTURE FOR AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT James O. Coplien Gertrud Bjørnvig JOHN WILEY AND SONS Chichester • New York • Brisbane • Toronto • Singapore Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Wiley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been pointed in initial caps or all caps. The authors and publishers have taken care in the preparation of this book, but make not expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omis- sions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coplien, James O. and Gertrud Bjørnvig Lean Software Architecture and Agile Production / James O. Coplien and Gertrud Bjørnvig. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-XXX-YYYYY-1 C++ (Computer program language) I. Title QA7673C153C675 2010 05. 13’3-dcl21 08-36336 CIP Copyright ©2010 James O. Coplien and Gertrud Bjørnvig. All rights reserved. -

The Origins of Pattern Theory the Future of the Theory, and the Generation of a Living World

THE ORIGINS OF PATTERN THEORY THE FUTURE OF THE THEORY, AND THE GENERATION OF A LIVING WORLD Christopher Alexander Introduction by James O. Coplien nce in a great while, a great idea makes it across the boundary of one discipline to take root in another. The adoption of Christopher O Alexander’s patterns by the software community is one such event. Alexander both commands respect and inspires controversy in his own discipline; he is the author of several books with long-running publication records, the first recipient of the AIA Gold Medal for Research, a member of the Swedish Royal Academy since 1980, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, recipient of dozens of awards and honors including the Best Building in Japan award in 1985, and the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Distinguished Professor Award. It is odd that his ideas should have found a home in software, a discipline that deals not with timbers and tiles but with pure thought stuff, and with ephemeral and weightless products called programs. The software community embraced the pattern vision for its relevance to problems that had long plagued software design in general and object-oriented design in particular. September/October 1999 IEEE Software 71 Focusing on objects had caused us to lose the pattern discipline that the software community has system perspective. Preoccupation with design yet scarcely touched: the moral imperative to build method had caused us to lose the human perspec- whole systems that contribute powerfully to the tive. The curious parallels between Alexander’s quality of life, as we recognize and rise to the re- world of buildings and our world of software con- sponsibility that accompanies our position of influ- struction helped the ideas to take root and thrive in ence in the world. -

Assessing Alexander's Later Contributions to a Science of Cities

Review Assessing Alexander’s Later Contributions to a Science of Cities Michael W. Mehaffy KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 114 28 Stockholm, Sweden; mmehaff[email protected] or michael.mehaff[email protected] Received: 23 April 2019; Accepted: 28 May 2019; Published: 30 May 2019 Abstract: Christopher Alexander published his longest and arguably most philosophical work, The Nature of Order, beginning in 2003. Early criticism assessed that text to be a speculative failure; at best, unrelated to Alexander’s earlier, mathematically grounded work. On the contrary, this review presents evidence that the newer work was a logically consistent culmination of a lifelong and remarkably useful inquiry into part-whole relations—an ancient but still-relevant and even urgent topic of design, architecture, urbanism, and science. Further evidence demonstrates that Alexander’s practical contributions are remarkably prodigious beyond architecture, in fields as diverse as computer science, biology and organization theory, and that these contributions continue today. This review assesses the potential for more particular contributions to the urban professions from the later work, and specifically, to an emerging “science of cities.” It examines the practical, as well as philosophical contributions of Alexander’s proposed tools and methodologies for the design process, considering both their quantitative and qualitative aspects, and their potential compatibility with other tools and strategies now emerging from the science of cities. Finally, it highlights Alexander’s challenge to an architecture profession that seems increasingly isolated, mired in abstraction, and incapable of effectively responding to larger technological and philosophical challenges. Keywords: Christopher Alexander; The Nature of Order; pattern language; structure-preserving transformations; science of cities 1.