Stax Oral Histories: Mavis Staples Interviewer: Interviewer Staples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Bobby Sanabria Reflects on His New Role at WBGO, and a Life of Advocacy for Latin Jazz

Bobby Sanabria Reflects on His New Role at WBGO, And a Life of Advocacy For Latin Jazz By NATE CHINEN • 8 HOURS AGO Latin Jazz Cruise TwitterFacebookGoogle+Email Bobby Sanabria, the new host of Latin Jazz Cruise, in the studio at WBGO. NATE CHINEN / WBGO Bobby Sanabria was a teenager, growing up in the Bronx, when he placed his first call to a radio station. The station was WRVR, a beacon of jazz in the New York area at the time, and he was calling to request a song by vibraphonist Cal Tjader. “I asked for ‘Cuban Fantasy’ — the live version from an album called Concert on the Campus,” Sanabria recalls. “Willie Bobo takes an incredible timbale solo on that track. As a percussionist, that was something I knew I needed to study.” To his surprise and dismay, the DJ at the station brusquely replied that “Cuban Fantasy” was Latin music, and had no place on a jazz program. Then he hung up. Sanabria called back again, and again and again, until finally his protestations got the song played on the air. But why had it been such a struggle? “That was when I realized this branch of the music was not considered part of the mainstream by the jazz intelligentsia,” Sanabria says. “I guess you could call that my first ‘A-ha moment’ of being an advocate. I always remember that. And I always will be a champion for this art form.” Sanabria is about to bring that passion to a new platform as the incoming host of Latin Jazz Cruise, which broadcasts on Fridays from 9 to 11 p.m. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago Jennifer Searcy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 The oiceV of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago Jennifer Searcy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Recommended Citation Searcy, Jennifer, "The oV ice of the Negro: African American Radio, WVON, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Chicago" (2012). Dissertations. Paper 688. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/688 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Jennifer Searcy LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE VOICE OF THE NEGRO: AFRICAN AMERICAN RADIO, WVON, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN CHICAGO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY/PUBLIC HISTORY BY JENNIFER SEARCY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Jennifer Searcy, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation committee for their feedback throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. As the chair, Dr. Christopher Manning provided critical insights and commentary which I hope has not only made me a better historian, but a better writer as well. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Definitive Collection of Stax Records' Singles to Be

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: DEFINITIVE COLLECTION OF STAX RECORDS’ SINGLES TO BE REISSUED Two volumes, due out December 16, 2014 and Spring 2015, cover 1968-1975. Volumes to be made available digitally for first time. LOS ANGELES, Calif. — Concord Music Group and Stax Records are proud to announce the digital release and physical reissue of two comprehensive box set titles: The Complete Stax/Volt Soul Singles, Vol. 2: 1968-1971 and The Complete Stax/Volt Soul Singles, Vol. 3: 1972-1975. Originally released in 1993 and 1994, respectively, these two compilations will be re-released back into the physical market in compact and sleek new packaging. Each set includes full-color booklets with in-depth essays by Stax historian and compilations co- producer Rob Bowman. The volumes feature stalwart Stax R&B artists including Isaac Hayes, the Staple Singers, Rufus Thomas, Johnnie Taylor, Carla Thomas, the Bar-Kays and William Bell, as well as bluesmen Little Milton, Albert King and Little Sonny, and “second generation” Stax hitmakers like Jean Knight, the Soul Children, Kim Weston, the Temprees, and Mel & Tim. Many of the tracks included in these collections will be made available digitally for the very first time. The story of the great Memphis soul label Stax/Volt can be divided into two distinct eras: the period from 1959 through the beginning of 1968, when the company was distributed by Atlantic and was developing its influential sound and image (chronicled in acclaimed 9-CD box set The Complete Stax/Volt Singles 1959-1968, released by Atlantic in 1991); and the post-Atlantic years, from May 1968 through the end of 1975, when Stax/Volt began its transition from a small, down-home enterprise to a corporate soul powerhouse. -

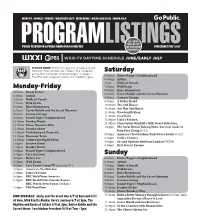

Program Listings

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW JUNE/EARLY JULY 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE JUNE/EARLY JULY PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete Saturday prime time television schedule begins on page 2. The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 6:30am Arthur 9:00am Curious George 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:30am A Wider World 7:30am Wild Kratts 10:00am This Old House 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:30am Ask This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:00am Curious George 11:30am Ciao Italia 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show/Survival Guide to 11:00am Sesame Street Pain Free Living (6/12) 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen/Rick Steves Awaits (6/12) 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! Sunday 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:00am Mister -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. October 15, 2018 to Sun. October 21, 2018

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. October 15, 2018 to Sun. October 21, 2018 Monday October 15, 2018 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT John Mayer With Special Guest Buddy Guy The Big Interview John Mayer’s soulful lyrics, convincing vocals, and guitar virtuosity have gained him worldwide Dwight Yoakam - Country music trailblazer takes time from his latest tour to discuss his career fans and Grammy Awards. John serenades the audience with hits like “Neon”, “Daughters” and and how he made it big in the business far from Nashville. “Your Body is a Wonderland”. Buddy Guy joins him in this special performance for the classic “Feels Like Rain”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT The Big Interview 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Emmylou Harris - Spend an hour with Emmylou Harris, as Dan Rather did, and you’ll see why she The Life & Songs of Emmylou Harris: An All-Star Concert Celebration is a legend in music. Shot in January 2015, this concert features performances by Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Conor Oberst, Daniel Lanois, Iron & Wine, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Martina McBride, 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT Mary Chapin Carpenter, Mavis Staples, Patty Griffin, Rodney Crowell, Sara Watkins, Shawn The Life & Songs of Emmylou Harris: An All-Star Concert Celebration Colvin, Sheryl Crow, Shovels & Rope, Steve Earle, The Milk Carton Kids, Trampled By Turtles, Vince Shot in January 2015, this concert features performances by Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Gill, and Buddy Miller. Conor Oberst, Daniel Lanois, Iron & Wine, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Martina McBride, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Mavis Staples, Patty Griffin, Rodney Crowell, Sara Watkins, Shawn 11:00 PM ET / 8:00 PM PT Colvin, Sheryl Crow, Shovels & Rope, Steve Earle, The Milk Carton Kids, Trampled By Turtles, Vince Rock Legends Gill, and Buddy Miller. -

P36-40 Layout 1

lifestyle TUESDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2016 MUSIC & MOVIES Bob Dylan sends speech for Nobel ceremony usic icon Bob Dylan won't be at the Nobel prize cere- in a letter on November 16 that he would not attend the cere- "Absolutely. If it's at all possible." mony this week to accept his award, but he has sent mony because he had "pre-existing commitments", in an Academy member Swedish writer Per Wastberg accused Malong a speech to be read aloud, the Nobel founda- announcement that did not come as a surprise to observers. Dylan of being "impolite and arrogant", and said it was tion said yesterday. The 75-year-old, whose lyrics have influ- Several other prize winners have skipped the Nobel ceremony "unprecedented" that the academy did not know if Dylan enced generations of fans, has had a subdued response to the in the past for various reasons-Doris Lessing, who was too old; intended to pick up his award. But the first songwriter to win honor, remaining silent for weeks following the news in Harold Pinter, because he was hospitalized, and Elfriede the prestigious award in literature is expected to come to October he had won the prize for literature. "This year's Jelinek, who has social phobia. Stockholm early next year. Nobel laureates are honored every Laureate in Literature, Bob Dylan, will not be participating in Dylan did not say a word about his prize on the day it was year on December 10 -- the anniversary of the death of prize's the Nobel Week but he has provided a speech which will be announced, October 13, when he was performing in Las founder Alfred Nobel, a Swedish industrialist, inventor and read at the banquet," the foundation said in a statement. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at the Kennedy Center

Administration of Barack Obama, 2016 Remarks at the Kennedy Center Honors Reception December 4, 2016 The President. Well, good evening, everybody. Audience members. Good evening! The President. On behalf of Michelle and myself, welcome to the White House. Over the past 8 years, this has always been one of our favorite nights. And this year, I was especially looking forward to seeing how Joe Walsh cleans up. [Laughter] Pretty good. [Laughter] I want to begin by once again thanking everybody who makes this wonderful evening possible, including David Rubenstein, the Kennedy Center Trustees—I'm getting a big echo back there—and the Kennedy Center President, Deborah Rutter. Give them a big round of applause. We have some outstanding Members of Congress here tonight. And we are honored also to have Vicki Kennedy and three of President Kennedy's grandchildren with us here: Rose, Tatiana, and Jack. [Applause] Hey! So the arts have always been part of life at the White House because the arts are always central to American life. And that's why, over the past 8 years, Michelle and I have invited some of the best writers and musicians, actors, dancers to share their gifts with the American people, and to help tell the story of who we are, and to inspire what's best in all of us. Along the way, we've enjoyed some unbelievable performances. This is one of the perks of the job that I will miss. [Laughter] Thanks to Michelle's efforts, we've brought the arts to more young people, from hosting workshops where they learn firsthand from accomplished artists, to bringing "Hamilton" to students who wouldn't normally get a ticket to Broadway. -

Second City Cracks up Crowd

Eastern Illinois University The Keep October 2008 10-27-2008 Daily Eastern News: October 27, 2008 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2008_oct Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: October 27, 2008" (2008). October. 17. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2008_oct/17 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 2008 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in October by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. 97 I ISSUE 44 CITY I COURTS Doctor says Bonnstetter likely was sleepwalking Her tests showed associate athletic director has signs of sleep disorders; state will call rebuttal witness today By STEPHEN DI BENEDETTO News Editor Or. Rosalind Cartwrighr believes Mark Bonnstetter was sleepwalking when he entered a neighbor's home during the early morn}ng of Nov. 25, 2006. "My opinion is yes, he was," Carrwrighc told che jury on whether Bonnscetter was sleep walking. Cartwright and Dr. Donald Greeley testi fied Friday. Bonnstetter, the associate athletic direccor of operations and head athletic trainer ar Easccrn, was charged with criminal trespass ro a residence. a class 4 felony; residential bur glary. .i class l felony; and arrempred criminal sexual .ibusc, a class A misdemeanor. Canwrighc, who recently retired from Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said Bonnsrerrer could nor have chougbt abour the ll0881t!WR08UWSK1 I THE 01\JLY EASTERN NEWS repercussions of his actions while in the neigh Second City members Mark Raterman and May Sohn perform a skit about awkward first-date situations in the Mainstage Theatre bor's home and could not have had a men o the Doudna fine Arts Center on Saturday evening. -

In the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the NINTH CIRCUIT

CA Nos. 15-56880, 16-55089, 16-55626 DC No. CV13-06004-JAK (AGRx) In the UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT Pharrell Williams et al. Plaintiffs, Appellants, and Cross-Appellees v. Frankie Christian Gaye et al., Defendants, Appellees, Cross-Appellants On Appeal From The United States District Court For The Central District of California, Hon. John A. Kronstadt, District Judge, No. 13-cv-06004 JAK (AGRx) BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE INSTITUTE FOR INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MUSICIAN AND COMPOSERS AND LAW, MUSIC, AND BUSINESS PROFESSORS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES SEAN M. O’CONNOR LATEEF MTIMA STEVEN D. JAMAR INSTITUTE FOR INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND SOCIAL JUSTICE, INC. 707 MAPLE AVENUE ROCKVILLE MD 20850 Telephone: 202-806-8012 IDENTITIES OF MUSICIAN-COMPOSER AMICI Affiliations and credits represent only a portion of those for each amicus and are given for identification purposes only Brian Holland: Inducted into the Songwriter Hall of Fame, Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Soul Music Hall of Fame, and member of the legendary songwriting trio of Holland-Dozier-Holland. Mr. Holland has written or co- written 145 hits in the US, and 78 in the UK. Eddie Holland: Inducted into the Songwriter Hall of Fame, Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Soul Music Hall of Fame, and member of the legendary songwriting trio of Holland-Dozier-Holland. Mr. Holland has written or co- written 80 hits in the UK, and 143 in the US charts. McKinley Jackson: Mr. Jackson is known as one of Soul music’s greatest arrangers and producers. Mr. Jackson arranged nearly every song recorded for the Invictus/HotWax/Music Merchant labels.