American University Library 1-« °

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report January 1, 2011 – March 31, 2011

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative USAID Mali Mission Awards Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) 3-2011 Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report January 1, 2011 – March 31, 2011 INTSORMIL Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilusaidmali INTSORMIL, "Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report January 1, 2011 – March 31, 2011" (2011). USAID Mali Mission Awards. 21. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/intsormilusaidmali/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the International Sorghum and Millet Collaborative Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USAID Mali Mission Awards by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Transfer of Sorghum, Millet Production, Processing and Marketing Technologies in Mali Quarterly Report January 1, 2011 – March 31, 2011 USAID/EGAT/AG/ATGO/Mali Cooperative Agreement # 688-A-00-007-00043-00 Submitted to the USAID Mission, Mali by Management Entity Sorghum, Millet and Other Grains Collaborative Research Support Program (INTSORMIL CRSP) Leader with Associates Award: EPP-A-00-06-00016-00 INTSORMIL University of Nebraska 113 Biochemistry Hall P.O. Box 830748 Lincoln, NE 68583-0748 USA [email protected] Table of Contents -

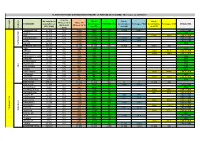

R E GION S C E R C L E COMMUNES No. Total De La Population En 2015

PLANIFICATION DES DISTRIBUTIONS PENDANT LA PERIODE DE SOUDURE - Mise à jour au 26/05/2015 - % du CH No. total de la Nb de Nb de Nb de Phases 3 à 5 Cibles CH COMMUNES population en bénéficiaires TONNAGE CSA bénéficiaires Tonnages PAM bénéficiaires Tonnages CICR MODALITES (Avril-Aout (Phases 3 à 5) 2015 (SAP) du CSA du PAM du CICR CERCLE REGIONS 2015) TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 12% 8 044 8 044 217 10 055 699,8 CSA + PAM ALAFIA 15 844 12% 1 901 1 901 51 CSA BER 23 273 12% 2 793 2 793 76 6 982 387,5 CSA + CICR BOUREM-INALY 14 239 12% 1 709 1 709 46 2 438 169,7 CSA + PAM LAFIA 9 514 12% 1 142 1 142 31 1 427 99,3 CSA + PAM SALAM 26 335 12% 3 160 3 160 85 CSA TOMBOUCTOU TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 18 748 18 749 506 13 920 969 6 982 388 DIRE 24 954 10% 2 495 2 495 67 CSA ARHAM 3 459 10% 346 346 9 1 660 92,1 CSA + CICR BINGA 6 276 10% 628 628 17 2 699 149,8 CSA + CICR BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 10% 1 050 1 050 28 CSA DANGHA 15 835 10% 1 584 1 584 43 CSA GARBAKOIRA 6 934 10% 693 693 19 CSA HAIBONGO 17 494 10% 1 749 1 749 47 CSA DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 10% 506 506 14 CSA KONDI 3 744 10% 374 374 10 CSA SAREYAMOU 20 794 10% 2 079 2 079 56 9 149 507,8 CSA + CICR TIENKOUR 8 009 10% 801 801 22 CSA TINDIRMA 7 948 10% 795 795 21 2 782 154,4 CSA + CICR TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 10% 356 356 10 CSA DIRE TOTAL 134 559 13 456 13 456 363 0 0 16 290 904 GOUNDAM 15 444 15% 2 317 9 002 243 3 907 271,9 CSA + PAM ALZOUNOUB 5 493 15% 824 3 202 87 CSA BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 15% 1 530 5 946 161 4 080 226,4 CSA + CICR ADARMALANE 1 172 15% 176 683 18 469 26,0 CSA + CICR DOUEKIRE 22 203 15% 3 330 -

ADMIS Tseco TOMBOUCTOU

LISTE DES ADMIS AU BACCALAUREAT MALIEN SESSION DE 2018 CENTRE DE CORRECTION DE TOMBOUCTOU SERIE: TERMINALES SCIENCES ECONOMIQUES (TSECO) N°PL PRENOMS NOM SEXE DATE DE NAISSANCE LIEU DE NAISSANCE ETABLISSEMENT NOMBRE ANNEE LYCEE STATUT ELEVE MENTION 10 Mahamane ABDRAMANE M 10/07/1999 Diré LDIRE 3 REG PASSABLE 12 Mohamed Ag ABZAW M 10/11/1998 Ber LPGMT 3 REG PASSABLE 15 Sidi Igoumo ADIAWIAKOYE M 31/05/1998 Rharous LRHAROUS 5 REG PASSABLE 29 Ibrahim Ag ALHASSANE M Rharous LRHAROUS 3 REG PASSABLE 31 Acheick Ag ALHOUSSEINI M Gossi LRHAROUS 4 REG PASSABLE 37 Chaibani ARBY M 11/03/2000 Tombouctou LBEYREY 3 REG PASSABLE 39 Faradji Baba ARBY M 11/10/1999 Tombouctou LMAHT 3 REG PASSABLE 45 Assa Mahamane ASCOFARE F 02/01/2001 Tombouctou LBEYREY 3 REG PASSABLE 48 Mohamed ATTAHER M 15/04/2000 Tombouctou LMAHT 4 REG PASSABLE 50 Hamed BABA M 11/01/2000 Tombouctou LPGMT 3 REG PASSABLE 51 Moïma BABA F 05/01/1998 Tombouctou LMAHT 4 CL PASSABLE 53 Kangeye BADOU M 12/07/1996 Tombouctou LMAHT 5 CL PASSABLE 55 Amadou BALIANDOU M 02/11/1996 Niafunké LBCN 3 REG PASSABLE 60 Youssouf BOCAR M 01/12/2000 Tombouctou LBEYREY 3 REG ASSEZ-BIEN 61 Mariama Wt BOHREIRATA F 23/12/1997 Tirikene LMAHT 5 REG PASSABLE 67 Hadji BOULKER M 13/12/1996 Tombouctou LMAHT 5 REG PASSABLE 70 Sira CAMARA F 24/03/1994 Boniaba LMAHT 6 CL PASSABLE 75 Agaly CISSE M 16/02/1997 Niono LDIRE 5 REG PASSABLE 80 Almihidi Alhamisse CISSE M 16/03/1998 Gossi LRHAROUS 4 REG PASSABLE 82 Assidé Ag Mossa CISSE M 20/07/1996 Tombouctou LMAHT 5 CL PASSABLE 83 Assietou Moussa CISSE F Tombouctou LMAHT 10 CL -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

0 16 32 48 64 8 Km

LOCALISATIONREGIONS REALISATIONS DE TOMBOUCTOU RELAC I & ET II / TOMBOUCTOUTAOUDENIT LOCALISATION REALISATION PROJETS RELAC I ET II Projet MLI/803 Relance de l’Economie locale et Appui aux Collectivités dans le Nord du Mali Avec la participation financière de l’UE ¯ REPUBLIQUE DU MALI SALAM C.TOMBOUCTOU BER TICHIFT DOUAYA INASTEL ELB ESBAT LYNCHA BER AIN RAHMA TINAKAWAT TAWAL C.BOUREM AGOUNI C.GOUNDAM ZARHO JIDID LIKRAKAR GABERI ATILA NIBKIT JAMAA TINTÉLOUT RHAROUS ERINTEDJEFT BER WAIKOUNGOU NANA BOUREM INALY DANGOUMA ALAFIA ALGABASTANE KEL ESSOUK TOBORAK NIKBKIT KAIDAM KEL ESSOUK ABOUA BENGUEL RHAROUS TOMBOUCTOU RHAROUS CAP ARAOUNE BOUGOUNI TINDIAMBANE TEHERDJE MINKIRI MILALA CT TOUEDNI IKOUMADEN DOUDARE BÉRÉGOUNGOU EMENEFAD HAMZAKOMA MORA TEDEYNI KEL INACHARIADJANDJINA KOIRA KABARA TERDIT NIBKITE KAIDAM ADIASSOU ARNASSEYEBELLESAO ZEINA DOUEKIRE NIBKIT KORIOME BOUREM INALY BORI KEL IKIKANE TIMBOUSE KELTIROU HOUNDOUBOMO TAGLIF INKARAN KAGA TOYA HEWA TILIMEDESS I INDALA ILOA KOULOUTAN II KELTAMOULEIT BT KEL ANTASSAR DJEGUELILA TASSAKANE IDJITANE ISSAFEYE DONGHOI TAKOUMBAOUT EDJAME ADINA KOIRA AGLAL DOUEKIRE KESSOU BIBI LAFIA NIAMBOURGOU HAMZAKONA ZINZIN 3 BOYA BABAGA AMTAGARE KATOUWA WANA KEL HARODJENE 2 FOUYA GOUNDAM DOUKOURIA KESSOU KOREY INTEDEINI EBAGAOU KEYNAEBAGAOU BERRI BORA CAMP PEUL GOYA SUD GARI KEL HAOUSSA IDJILAD KEL ERKIL ARHAM KOROMIA HARAM DIENO KEL ADRAR ARHAM KIRCHAMBA DOUKOURIA BAGADADJI GOUREIGA MORIKOIRA TANGASSANE DEBE DIAWATOU FOUTARD FADJIBAYENDE KIRCHAMBA DIAWATOU DOUTA KOUNDAR INATABANE CHÉRIF YONE KEL DJILBAROU -

Régions De SEGOU Et MOPTI République Du Mali P! !

Régions de SEGOU et MOPTI République du Mali P! ! Tin Aicha Minkiri Essakane TOMBOUCTOUC! Madiakoye o Carte de la ville de Ségou M'Bouna Bintagoungou Bourem-Inaly Adarmalane Toya ! Aglal Razelma Kel Tachaharte Hangabera Douekiré ! Hel Check Hamed Garbakoira Gargando Dangha Kanèye Kel Mahla P! Doukouria Tinguéréguif Gari Goundam Arham Kondi Kirchamba o Bourem Sidi Amar ! Lerneb ! Tienkour Chichane Ouest ! ! DiréP Berabiché Haib ! ! Peulguelgobe Daka Ali Tonka Tindirma Saréyamou Adiora Daka Salakoira Sonima Banikane ! ! Daka Fifo Tondidarou Ouro ! ! Foulanes NiafounkoéP! Tingoura ! Soumpi Bambara-Maoude Kel Hassia Saraferé Gossi ! Koumaïra ! Kanioumé Dianké ! Leré Ikawalatenes Kormou © OpenStreetMap (and) contributors, CC-BY-SA N'Gorkou N'Gouma Inadiatafane Sah ! ! Iforgas Mohamed MAURITANIE Diabata Ambiri-Habe ! Akotaf Oska Gathi-Loumo ! ! Agawelene ! ! ! ! Nourani Oullad Mellouk Guirel Boua Moussoulé ! Mame-Yadass ! Korientzé Samanko ! Fraction Lalladji P! Guidio-Saré Youwarou ! Diona ! N'Daki Tanal Gueneibé Nampala Hombori ! ! Sendegué Zoumané Banguita Kikara o ! ! Diaweli Dogo Kérengo ! P! ! Sabary Boré Nokara ! Deberé Dallah Boulel Boni Kérena Dialloubé Pétaka ! ! Rekerkaye DouentzaP! o Boumboum ! Borko Semmi Konna Togueré-Coumbé ! Dogani-Beré Dagabory ! Dianwely-Maoundé ! ! Boudjiguiré Tongo-Tongo ! Djoundjileré ! Akor ! Dioura Diamabacourou Dionki Boundou-Herou Mabrouck Kebé ! Kargue Dogofryba K12 Sokora Deh Sokolo Damada Berdosso Sampara Kendé ! Diabaly Kendié Mondoro-Habe Kobou Sougui Manaco Deguéré Guiré ! ! Kadial ! Diondori -

Geo-Epidemiology of Malaria at the Health Area Level, Dire Health District, Mali, 2013–2017

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Geo-Epidemiology of Malaria at the Health Area Level, Dire Health District, Mali, 2013–2017 Mady Cissoko 1,2,3,* , Issaka Sagara 1,2, Moussa H. Sankaré 3, Sokhna Dieng 2, Abdoulaye Guindo 1,4, Zoumana Doumbia 3, Balam Allasseini 3, Diahara Traore 5, Seydou Fomba 5, Marc Karim Bendiane 2, Jordi Landier 2, Nadine Dessay 6 and Jean Gaudart 1,7 1 Malaria Research and Training Center—Ogobara K. Doumbo (MRTC-OKD), FMOS-FAPH, Mali-NIAID-ICER, Université des Sciences, des Techniques et des Technologies de Bamako, Bamako 1805, Mali; [email protected] (I.S.); [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (J.G.) 2 Aix Marseille Université (AMU), Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM), Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), 13005 Marseille, France; [email protected] (S.D.); [email protected] (M.K.B.); [email protected] (J.L.) 3 Direction Régionale de la Santé de Tombouctou, Tombouctou 59, Mali; [email protected] (M.H.S.); [email protected] (Z.D.); [email protected] (B.A.) 4 Mère et Enfant face aux Infections Tropicales (MERIT), IRD, Université Paris 5, 75006 Paris, France 5 Programme National de la Lutte contre le Paludisme (PNLP Mali), Bamako 233, Mali; [email protected] (D.T.); [email protected] (S.F.) 6 ESPACE-DEV, UMR228 IRD/UM/UR/UG/UA, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), 34093 Montpellier, France; [email protected] 7 Aix Marseille Université, APHM, INSERM, IRD, SESSTIM, Hop -

Et Dangha (Cercle De Diré)

Coopération Allemande (GTZ/KfW) Programme Mali-Nord Mission de prospection dans les communes de Lafia et Alafia (cercle de Tombouctou), Haribomo (cercle de Gourma Rharous) et Dangha (cercle de Diré) réunion à Temeout le 22 février 2009 présenté par Yehia Ag Mohamed Ali Bamako, mars 2009 1 1. Introduction Une mission du Programme Mali-Nord (GTZ/KfW) s’est rendue dans les communes de Lafia (cercle de Tombouctou) et de Dangha (cercle de Diré) du 21 au 22 février 2009, La mission est composée de : - Nock Ag Attia (comité consultatif), - Yehia Ag Mohamed Ali, - Dr. Henner Papendieck, - Salaha Baby (chef d’antenne de Diré), - Boubacar Maïga (chef d’antenne de Rharous), - Aliou Maouloud (aménagiste). 2. Objectifs de la mission Cette mission complète la prospection commencée lors de la mission du 13 au 16 janvier 2009. Elle est destinée à évaluer le potentiel aménageable des zones visitées et à prendre contact avec les élus et notables locaux en vue d’identifier des personnes ressources crédibles pouvant garantir la réussite d’un éventuel programme d’aménagement de PIV et mares. 3. Déroulement de la mission Le 21 février la mission a emprunté la pinasse à partir de Koriomé pour longer le fleuve en direction de Kaga. Elle s’est arrêtée à Ewet (en face de Tombouctou) où elle a rencontré les notables de la fraction Kel Ahadsatafane. Là, les populations ont manifesté leur intérêt pour l’aménagement de 3 PIV de 40 hectares chacun, soit 120 hectares, PIV aménagés par différentes organisations : FENU, AFAR, UNICEF, etc. Le potentiel aménageable est apparemment suffisant. -

Case Studies on Conflict and Cooperation in Local Water Governance

Case studies on conflict and cooperation in local water governance Report No. 3 The case of Lake Agofou Douentza, Mali Signe Marie Cold-Ravnkilde 2010 Signe Marie-Cold Ravnkilde PhD Candidate, Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen, Denmark List of all Case Study Reports -in the Competing for Water Programme Tiraque, Bolivia Report No. 1: The case of the Tiraque highland irrigation conflict Report No. 2: The case of the Koari channel Douentza District, Mali Report No. 3: The case of Lake Agofou Report No. 4: The case of the Yaïre floodplain Report No. 5: The case of the Hombori water supply projects Condega District, Nicaragua Report No. 6: The case of “Las Brumas” community Report No. 7: The case of “San Isidro” community Report No. 8: The case of “Los Claveles” community Con Cuong District, Vietnam Report No. 9: The case of the Tong Chai lead mine Report No. 10: The case of the Yen Khe piped water system Namwala District, Zambia Report No. 11: The case of the Kumalesha Borehole Report No. 12: The case of the Mbeza irrigation scheme Report No. 13: The case of the Iliza Borehole For other publications and journal articles, see www.diis.dk/water Table of contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................................ 5 2. Methodology........................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Definitions........................................................................................................ -

DECEMBER 1988 Record Hat-Vest for Mali

FEWS Count,,r Rcport DECEMBER 1988 MALI Record Hat-vest for Mali FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM Produced by the Office of Technical Resources - Africa Bureau - USAID FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM The Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) is an Agency-wide effort coordinated by the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID). Its mission is to assemble, analyze and report on the complex conditions which may lead to famine in any one of the following drought-prone countries in Africa: * Burkina e Chad a Ethlpla * Mall * Mauritania * Niger a Sudan FEWS reflects the Africa Bureau's commitment to providiaig reliable and timely information to decision-makers within the Agency, within the seven countries, and among the broader donor community, so that they can take appropriate actions to avert a famine. FEWS relies on information it.obtains from a wide variety of sour cts including: USAID Missions, host governments, private voluntary organizations, international donor and relief agencies, and the remote sensing and academic communities. In addition, the FEWS system obtains information directly from FEWS Field Representatives cturctitly assigned to six USAID Missions. FEWS analyzes the information it collects, crosschecks and analyzes the data, and systematically disseminates its findings tbrough se:veral types of publications. In addition, FEWS servt..s the AID staff by: " preparing iEVVS Alert Memornda for distribution to top AID decision-makers when dictated by fast-breaking events; * preparing Special Reports, maps, briefings, anal3ies, etc. upon request; and " responding to special inquiries. Please note that this is the last monthly Country Report that will be published in this format. -

Archives, the Digital Turn and Governance in Africa Fabienne

This article has been published in a revised form in History in Africa, 47. pp. 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1017/hia.2019.26 This version is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND. No commercial re-distribution or re-use allowed. Derivative works cannot be distributed. © African Studies Association 2019 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34231 Archives, the Digital Turn and Governance in Africa Fabienne Chamelot PhD candidate University of Portsmouth School of Area Studies, History, Politics and Literature Park Building King Henry I Street Portsmouth PO1 2DZ United Kingdom +44(0)7927412143 [email protected] Dr Vincent Hiribaren Senior Lecturer in Modern African History History Department King’s College London Strand London, WC2R 2LS United Kingdom 1 [email protected] Dr Marie Rodet Senior Lecturer in the History of Africa SOAS University of London School of History, Philosophies and Religion Studies 10 Thornhaugh Street Russell Square London WC1H 0XG United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7898 4606 [email protected] 2 Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Yann Potin, along with the scholars who kindly suggested changes to our introduction at the European Conference of African Studies (2019) and those who agreed to participate in the peer-review process. 3 This manuscript has not been previously published and is not under review for publication elsewhere. 4 Fabienne Chamelot is a PhD student at the University of Portsmouth. Her research explores the making of colonial archives in the 20th century, with French West Africa and the Indochinese Union as its specific focus. -

I I I I I Cooperative Agreement No

I PD-A ~ T-I 69 I Medical Care Development International 1742 R Street NW, Washington, DC 20009 * USA Telephone: (202) 462-1920; Fax: (202) 265-4078 I Internet Electronic Mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.mcd.org I I Northern Region Health and Hygiene Project Timbuktu Region, Mali I Semi-Annual Report I September 25 - December 31, 2000 I () 200 ~OOkm ~ d f' I i o 201) <'lOOml I ALGERIA I MAURiTANIA I I I I I Cooperative Agreement No. 688-A-00-OO-00353-00 I Start Date: 9/25/2000 End Date: 6/30/2003 I Submission Date: I February 28, 2001 I I Medical Care Development International - Timbuktu Region Northern Region Health and Hygiene Project - Semi-Annual Report September - December 2000 I Northern Region Health and Hygiene Project I The Northern Region Health and Hygiene Project (NRHHP), working in the Circles ofTimbuktu and Gourma-Rharous, began operating September 25, 2000. These first few months of the project primarily involved the setup of the office, procurement of equipment and supplies, I recruitment of personnel, the introduction of the project to authorities and communities, program planning, and the collection of baseline data. I Activities I October ~ Office setup and equipment procurement ~ Recruitment of personnel I o 1 Water and sanitation coordinator (Louis Haldin) o 1 Health Educator (Fatty Amoye) o 2 Animators (Elmounzer Ag Jiddou, Hawa Toure) I o 1 Administrator (Hamadoun HaYdara) o 1 Accountant/logistician (Cheick Bounama Cisse) o 2 Drivers I o 2 Guards ~ Informed government technical and administrative services of project, including goals, I objectives, and strategies.