The Political Economy of Computer Game Culture Justin Schumaker University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 18 Issue 3 Issue 3 - Spring 2016 Article 2 2015 Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games Julian Dibbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Internet Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Julian Dibbell, Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games, 18 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 419 (2021) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol18/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT JOURNAL OF ENTERTAINMENT & TECHNOLOGY LAW VOLUME 18 SPRING 2016 NUMBER 3 Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games Julian Dibbell ABSTRACT When does work become play and play become work? Courts have considered the question in a variety of economic contexts, from student athletes seeking recognition as employees to professional blackjack players seeking to be treated by casinos just like casual players. Here, this question is applied to a relatively novel context: that of online gold farming, a gray-market industry in which wage-earning workers, largely based in China, are paid to play fantasy massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) that reward them with virtual items that their employers sell for profit to the same games' casual players. -

Offworld Trading Company V1.21 Brings Updated Language Support

Offworld Trading Company v1.21 brings updated language support for both base game and DLCs The best selling economic real-time strategy game now have updated translations in Simplified Chinese, Russian, German, and more. Plymouth, MI. – November 1, 2018 - Today, Stardock announced the release of v1.21 for Offworld Trading Company, a game in which players take on the role of entrepreneur and travel to Mars for an economic showdown against rival companies. The version update improves localization for several languages and adds some balance updates that enhance the gameplay experience. In Offworld Trading Company, players buy out the competition and take control of the Martian market in a strategy game where money, not military force, is their greatest weapon. The real-time, player-driven market is the foundation of the game, allowing players to buy and sell resources and materials - even the food and water that the colonists need to survive. Players will also have to deal with some underhanded black market methods of sabotage, like pirate raiders, hackers trying to disrupt production, covert electromagnetic pulses, and more. The game supports online match play with up to 8 players, as well as single player campaigns, skirmishes, or daily challenges. For more serious players, ranked ladder games will give them the opportunity to earn ranks and prove their worth. The v1.21 update adds improved localization in both the base game and all of Offworld Trading Company’s DLC for the following languages: ● Simplified Chinese ● German ● French ● Spanish ● Korean ● Polish ● Russian ● Brazilian Portuguese Offworld Trading Company is $19.99 through Steam or Stardock. -

The Video Game Industry an Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective

The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Nik Shah T’05 MBA Fellows Project March 11, 2005 Hanover, NH The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Authors: Nik Shah • The video game industry is poised for significant growth, but [email protected] many sectors have already matured. Video games are a large and Tuck Class of 2005 growing market. However, within it, there are only selected portions that contain venture capital investment opportunities. Our analysis Charles Haigh [email protected] highlights these sectors, which are interesting for reasons including Tuck Class of 2005 significant technological change, high growth rates, new product development and lack of a clear market leader. • The opportunity lies in non-core products and services. We believe that the core hardware and game software markets are fairly mature and require intensive capital investment and strong technology knowledge for success. The best markets for investment are those that provide valuable new products and services to game developers, publishers and gamers themselves. These are the areas that will build out the industry as it undergoes significant growth. A Quick Snapshot of Our Identified Areas of Interest • Online Games and Platforms. Few online games have historically been venture funded and most are subject to the same “hit or miss” market adoption as console games, but as this segment grows, an opportunity for leading technology publishers and platforms will emerge. New developers will use these technologies to enable the faster and cheaper production of online games. The developers of new online games also present an opportunity as new methods of gameplay and game genres are explored. -

Sports & Esports the Competitive Dream Team

SPORTS & ESPORTS THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM JULIANA KORANTENG Editor-in-Chief/Founder MediaTainment Finance (UK) SPORTS & ESPORTS: THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM 1.THE CROSSOVER: WHAT TRADITIONAL SPORTS CAN BRING TO ESPORTS Professional football, soccer, baseball and motor racing have endless decades worth of experience in professionalising, commercialising and monetising sporting activities. In fact, professional-services powerhouse KPMG estimates that the business of traditional sports, including commercial and amateur events, related media as well as education, academic, grassroots and other ancillary activities, is a US$700bn international juggernaut. Furthermore, the potential crossover with esports makes sense. A host of popular video games have traditional sports for themes. Soccer-centric games include EA’s FIFA series and Konami’s Pro Evolution Soccer. NBA 2K, a series of basketball simulation games published by a subsidiary of Take-Two Interactive, influenced the formation of the groundbreaking NBA 2K League in professional esports. EA is also behind the Madden NFL series plus the NHL, NBA, FIFA and UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship) games franchises. Motor racing has influenced the narratives in Rockstar Games’ Grand Theft Auto, Gran Turismo from Sony Interactive Entertainment, while Psyonix’s Rocket League melds soccer and motor racing. SPORTS & ESPORTS THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM SPORTS & ESPORTS: THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM In some ways, it isn’t too much of a stretch to see why traditional sports should appeal to the competitive streaks in gamers. Not all those games, several of which are enjoyed by solitary players, might necessarily translate well into the head-to-head combat formats associated with esports and its millions of live-venue and online spectators. -

Consumer Motivation, Spectatorship Experience and the Degree of Overlap Between Traditional Sport and Esport.”

COMPETITIVE SPORT IN WEB 2.0: CONSUMER MOTIVATION, SPECTATORSHIP EXPERIENCE, AND THE DEGREE OF OVERLAP BETWEEN TRADITIONAL SPORT AND ESPORT by JUE HOU ANDREW C. BILLINGS, COMMITTEE CHAIR CORY L. ARMSTRONG KENON A. BROWN JAMES D. LEEPER BRETT I. SHERRICK A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Journalism and Creative Media in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2019 Copyright Jue Hou 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In the 21st Century, eSport has gradually come into public sight as a new form of competitive spectator event. This type of modern competitive video gaming resembles the field of traditional sport in multiple ways, including players, leagues, tournaments and corporate sponsorship, etc. Nevertheless, academic discussion regarding the current treatment, benefit, and risk of eSport are still ongoing. This research project examined the status quo of the rising eSport field. Based on a detailed introduction of competitive video gaming history as well as an in-depth analysis of factors that constitute a sport, this study redefined eSport as a unique form of video game competition. From the theoretical perspective of uses and gratifications, this project focused on how eSport is similar to, or different from, traditional sports in terms of spectator motivations. The current study incorporated a number of previously validated-scales in sport literature and generated two surveys, and got 536 and 530 respondents respectively. This study then utilized the data and constructed the motivation scale for eSport spectatorship consumption (MSESC) through structural equation modeling. -

Esports Live Broadcast: an Appealing Media for Business-To-Consumer Communication

Internationale Betriebswirtschaft B.A. Hochschule Furtwangen University, Business School Supervised by Prof. Dr. Christoph Mergard eSports live broadcast: An appealing media for business-to-consumer communication A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor’s of Arts in the faculty of economy by Daniel Fritz Matriculation number 248343 IBW 7 Pestalozzistr. 21 78176 Blumberg [email protected] June 2018 Table of contents Sworn Statement........................................................................................................................... II List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... III Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ IV Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 Scope of study ....................................................................................................................... 2 Literature review ........................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 7 1. Examination of the eSports industry and eSport live broadcasts ............................................ -

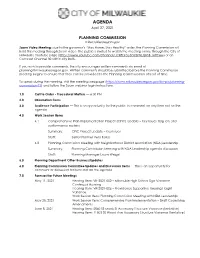

Planning Comission Packet 04.27.2021

AGENDA April 27, 2021 PLANNING COMMISSION milwaukieoregon.gov Zoom Video Meeting: due to the governor’s “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order, the Planning Commission will hold this meeting through Zoom video. The public is invited to watch the meeting online through the City of Milwaukie YouTube page (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRFbfqe3OnDWLQKSB_m9cAw) or on Comcast Channel 30 within city limits. If you wish to provide comments, the city encourages written comments via email at [email protected]. Written comments should be submitted before the Planning Commission meeting begins to ensure that they can be provided to the Planning Commissioners ahead of time. To speak during the meeting, visit the meeting webpage (https://www.milwaukieoregon.gov/bc-pc/planning- commission-71) and follow the Zoom webinar login instructions. 1.0 Call to Order - Procedural Matters — 6:30 PM 2.0 Information Items 3.0 Audience Participation — This is an opportunity for the public to comment on any item not on the agenda 4.0 Work Session Items 4.1 Comprehensive Plan Implementation Project (CPIC) Update – Key Issues: flag lots and performance metrics Summary: CPIC Project Update – Key Issues Staff: Senior Planner Vera Kolias 4.2 Planning Commission Meeting with Neighborhood District Association (NDA)Leadership Summary: Planning Commission Meeting with NDA Leadership agenda discussion Staff: Planning Manager Laura Weigel 5.0 Planning Department Other Business/Updates 6.0 Planning Commission Committee Updates and Discussion Items — This is an opportunity -

Gold Farming” HEEKS

Understanding “Gold Farming” HEEKS Forum Understanding “Gold Farming”: Developing-Country Production for Virtual Gameworlds Richard Heeks Gold farming is the production of virtual goods and services for players of richard.heeks@manchester online games. It consists of real-world sales of in-game currency and asso- .ac.uk ciated items, including “high-level” game characters. These are created by Development Informatics “playborers”—workers employed to play in-game—whose output is sold Group for real money through various Web sites in so-called “real-money trad- Institute for Development ing.” Policy and Management There is growing academic interest in online games, including aspects School of Environment and Development such as real-money trading and gold farming (see, for example, Terra University of Manchester Nova, where much of this work is reported and discussed). However, there United Kingdom appear to be few, if any, academic publications looking at gold farming from a developing-country angle, and development agencies seem to have completely ignored it. That is problematic for three reasons. First, as described below, gold farming is already a signiªcant social and economic activity in developing countries. Second, it represents the ªrst example of a likely future devel- opment trend in outsourcing of online employment—what we might oth- erwise call “cybersourcing.” Third, it is one of a few emerging examples in developing countries of “liminal ICT work”—jobs associated with digi- tal technologies that exist on the edge of, or just below the threshold of, that which is deemed socially acceptable and/or formally legal. In basic terms, gold farming is a sizable developing-country phenome- non. -

Intel ESS Digital Extremes Case Study

case STUDY Intel® Solid-State Drives Performance: Data-Intensive Computing Delivering extreme entertainment with Intel® Solid-State Drives Intel® Solid-State Drives help Digital Extremes increase the efficiency of game development and maximize innovation Co-creators of the immensely popular Unreal* series of video games and current producers of several AAA game titles, Digital Extremes is among the most successful game development studios in the world. Sustaining that success requires not only a constant stream of creativity but also an extreme focus on internal efficiency. To speed up key production tasks, the company recently replaced traditional hard disk drives with Intel® Solid-State Drives in several workstations. By accelerating source-code build times up to 46 percent and increasing the speed of other production processes more than 100 percent, the new drives enable development teams to experiment with more creative possibilities while still meeting tight deadlines. CHALLENGE • Increase process efficiency. Maintain a competitive edge by increasing the efficiency of numerous production tasks, from completing new source-code builds to encoding content for multiple game platforms. SOLUTION • Intel® Solid-State Drives. Digital Extremes replaced traditional serial ATA (SATA) hard disk drives with Intel® X25-M Mainstream SATA Solid-State Drives (SSDs) in worksta- tions used by programmers and artists. IMPacT • Faster builds, increased innovation. The Intel SSD solution helped accelerate source-code build times by up to 46 percent, enabling development teams to rapidly incorporate testing feedback and giving them time to explore additional creative ideas without increasing costs. • Rapid ROI. By saving time with key processes, Digital Extremes could recoup the cost of each drive within a month. -

Time War: Paul Virilio and the Potential Educational Impacts of Real-Time Strategy Videogames

Philosophical Inquiry in Education, Volume 27 (2020), No. 1, pp. 46-61 Time War: Paul Virilio and the Potential Educational Impacts of Real-Time Strategy Videogames DAVID I. WADDINGTON Concordia University This essay explores the possibility that a particular type of video game—real-time strategy games—could have worrisome educational impacts. In order to make this case, I will develop a theoretical framework originally advanced by French social critic Paul Virilio. In two key texts, Speed and Politics (1977) and “The Aesthetics of Disappearance” (1984), Virilio maintains that society is becoming “dromocratic” – determined by and obsessed with speed. Extending Virilio’s analysis, I will argue that the frenetic, ruthless environment of real-time strategy games may promote an accelerated, hypermodern way of thinking about the world that focuses unduly on efficiency. Introduction Video games have been a subject of significant interest lately in education. A new wave of momentum began when James Paul Gee’s book, What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy (2003a), was critically acclaimed, and was followed by a wave of optimistic studies and analyses. In 2010, a MacArthur Foundation report, The Civic Potential of Video Games, built on this energy, drawing on large-scale survey data to highlight the possibility that games that certain popular types of video games might promote civic engagement in the form of increased political participation and volunteerism. The hypothesis that video games, a perpetual parental bête-noire and the site of many a sex/violence media panic, might actually be educationally beneficial, has been gathering steam and is the preferred position of most educational researchers working in the field. -

Identifying Players and Predicting Actions from RTS Game Replays

Identifying Players and Predicting Actions from RTS Game Replays Christopher Ballinger, Siming Liu and Sushil J. Louis Abstract— This paper investigates the problem of identifying StarCraft II, seen in Figure 1, is one of the most popular a Real-Time Strategy game player and predicting what a player multi-player RTS games with professional player leagues and will do next based on previous actions in the game. Being able world wide tournaments [2]. In South Korea, there are thirty to recognize a player’s playing style and their strategies helps us learn the strengths and weaknesses of a specific player, devise two professional StarCraft II teams with top players making counter-strategies that beat the player, and eventually helps us six-figure salaries and the average professional gamer making to build better game AI. We use machine learning algorithms more than the average Korean [3]. StarCraft II’s popularity in the WEKA toolkit to learn how to identify a StarCraft II makes obtaining larges amounts of different combat scenarios player and predict the next move of the player from features for our research easier, as the players themselves create large extracted from game replays. However, StarCraft II does not have an interface that lets us get all game state information like databases of professional and amateur replays and make the BWAPI provides for StarCraft: Broodwar, so the features them freely available on the Internet [4]. However, unlike we can use are limited. Our results reveal that using a J48 StarCraft: Broodwar, which has the StarCraft: Brood War decision tree correctly identifies a specific player out of forty- API (BWAPI) to provide detailed game state information one players 75% of the time. -

Esports Marketer's Training Mode

ESPORTS MARKETER’S TRAINING MODE Understand the landscape Know the big names Find a place for your brand INTRODUCTION The esports scene is a marketer’s dream. Esports is a young industry, giving brands tons of opportunities to carve out a TABLE OF CONTENTS unique position. Esports fans are a tech-savvy demographic: young cord-cutters with lots of disposable income and high brand loyalty. Esports’ skyrocketing popularity means that an investment today can turn seri- 03 28 ous dividends by next month, much less next year. Landscapes Definitions Games Demographics Those strengths, however, are balanced by risk. Esports is a young industry, making it hard to navigate. Esports fans are a tech-savvy demographic: keyed in to the “tricks” brands use to sway them. 09 32 Streamers Conclusion Esports’ skyrocketing popularity is unstable, and a new Fortnite could be right Streamers around the corner. Channels Marketing Opportunities These complications make esports marketing look like a high-risk, high-reward proposition. But it doesn’t have to be. CHARGE is here to help you understand and navigate this young industry. Which games are the safest bets? Should you focus on live 18 Competitions events or streaming? What is casting, even? Competitions Teams Keep reading. Sponsors Marketing Opportunities 2 LANDSCAPE LANDSCAPE: GAMES To begin to understand esports, the tra- game Fortnite and first-person shooter Those gains are impressive, but all signs ditional sports industry is a great place game Call of Duty view themselves very point to the fact that esports will enjoy even to start. The sports industry covers a differently.