Reference Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

Living with the Chesapeake Bay Retriever (CBR) by Debra Wiley Cuevas, Quailridge Chesapeakes

Living with the Chesapeake Bay Retriever (CBR) by Debra Wiley Cuevas, QuailRidge Chesapeakes I have lived with many Chesapeake Bay Retrievers since 1985. They are wonderful dogs, loyal, intelligent, loving, protective, versatile and amazingly intuitive companions. They exhibit courage, endurance, persistence, and a terrific sense of humor. Once you have a Chesapeake, it is difficult to replace them with another breed, but they are not for everyone, they require an equally instinctive owner who is willing to be the Alpha. The CBR is a a dog with an instinct to protect loved ones. They bond closely with their family, and are generally neutral around other people and dogs. Their intelligence and ability to reason make them a challenge for the inexperienced dog owner. The first year of their life is crucial, this breed needs structure, socialization, and a solid foundation of obedience training. Obedience training at a young age will establish good behavior and decrease the tendency for willfulness and independence. CBRs need plenty of exercise and thrive in environments where they feel they have a job to do. The CBR needs to respect its owner, or trouble begins. If the Chesapeake feels the owner is not in charge, they will take charge, or in other words, become the "alpha" and handle things as they see fit. When giving an instruction it is imperative that the owner follow thru, if you are not willing to get up and make the CBR do what you have asked, don't ask, because the dog will quickly recognize an owner that does not follow thru and quickly loose respect for, then ignore the owner. -

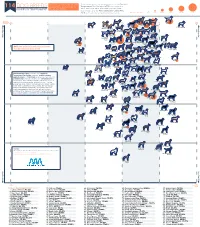

Ranked by Temperament

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

The American Water Spaniel: Yankee Doodle Dandy

The American Water Spaniel: Yankee Doodle Dandy James B. Spencer HUP! Training Flushing Spaniels The American Way he American Water Spaniel (AWS) is as American as George M. Cohan, and just as capable of “doing it all” in his particular line of work. T A marvelous little all-weather ducker, the AWS can also bust the nastiest cover in the uplands to flush and retrieve birds for the boss. The dog’s small size and placid temperament make him ideal in a duck skiff, where he can slip into and out of the water without upsetting or soaking the skipper. His methodical thoroughness in the uplands makes him a delightful companion for the gunner over thirty-five years of age. Developed in the last century in the Great Lakes region, and now the state dog of Wisconsin, this native breed possesses so many talents that the national breed club, American Water Spaniel Club (AWSC), has struggled for years trying to decide whether to seek AKC classification as a retriever or as a flushing spaniel. The breed must be classified as one or the other before it can participate in AKC Field Trials and hunting tests. The breed needs the exposure these activities, especially the AKC hunting tests, would give it among dog-loving hunters. Trouble is, the AWSC membership is badly split – four ways. Some members favor classification as a spaniel. Some favor classification as a retriever. Others fearing that either would eventually damage the breed’s dual abilities, have until very recently held out for dual classification. Still others prefer no classification at all. -

Application for Dog License

DOG IDENTIFICATION RICHARD LaMARCA, TOWN CLERK License No. Microchip No. TOWN OF OYSTER BAY 54 AUDREY AVENUE RABIES CERTIFICATE REQUIRED OYSTER BAY, NY 11771 Rabies Vaccine: Date Issued Expiration Date (516) 624-6324 Manufacturer __________________________ Dog Breed Code DOG LICENSE Serial Number __________________________ Dog Color(s) Code(s) Issuing County Code – 2803 One Year Vacc. Three Year Vacc. Other ID Dog’s Yr. of LICENSE TYPE Date Vaccinated ______________________ Birth Last 2 Digits ORIGINAL RENEWAL Veterinarian ______________________________ Markings Dog’s Name TRANSFER OF OWNERSHIP OWNER’S PHONE NO. Owner Identification (Person who harbors or keeps dog): Last First Middle Initial Area Code Mailing Address: House No. Street or R.D. No. and P.O. Box No. Phone No. City State Zip County Town, City or Village TYPE OF LICENSE Fee LICENSE FEE____________________ 1.Male, neutered 10.00 2.Female, spayed 10.00 SPAY/NEUTER FEE_______________ 3. Male, unneutered ENUMERATION FEE______________ under 4 months 15.00 4 mos. & over 15.00 TOTAL FEE_______________________ 4. Female, unspayed under 4 months 15.00 4 mos. & over 15.00 IS OWNER LESS THAN 18 YEARS OF AGE? YES NO IF YES, PARENT OR GUARDIAN SHALL BE DEEMED THE 5.Exempt dogs: Guide, War, NO FEE OWNER OF RECORD AND THE INFORMATION MUST BE COMPLETED BY THEM. Police, Detection Dog, Therapy Dog, Working Search, Hearing and Service 6. Senior Citizen (Age 62+) 5.00 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Owner’s Signature Date Clerk’s Signature Date OWNER’S INSTRUCTIONS 1. All dogs 4 months of age or older are to be licensed. In addition, any dog under 4 months of age, if running at large must be licensed. -

Best in Grooming Best in Show

Best in Grooming Best in Show crownroyaleltd.net About Us Crown Royale was founded in 1983 when AKC Breeder & Handler Allen Levine asked his friend Nick Scodari, a formulating chemist, to create a line of products that would be breed specific and help the coat to best represent the breed standard. It all began with the Biovite shampoos and Magic Touch grooming sprays which quickly became a hit with show dog professionals. The full line of Crown Royale grooming products followed in Best in Grooming formulas to meet the needs of different coat types. Best in Show Current owner, Cindy Silva, started work in the office in 1996 and soon found herself involved in all aspects of the company. In May 2006, Cindy took full ownership of Crown Royale Ltd., which continues to be a family run business, located in scenic Phillipsburg, NJ. Crown Royale Ltd. continues to bring new, innovative products to professional handlers, groomers and pet owners worldwide. All products are proudly made in the USA with the mission that there is no substitute for quality. Table of Contents About Us . 2 How to use Crown Royale . 3 Grooming Aids . .3 Biovite Shampoos . .4 Shampoos . .5 Conditioners . .6 Finishing, Grooming & Brushing Sprays . .7 Dog Breed & Coat Type . 8-9 Powders . .10 Triple Play Packs . .11 Sporting Dog . .12 Dilution Formulas: Please note when mixing concentrate and storing them for use other than short-term, we recommend mixing with distilled water to keep the formulas as true as possible due to variation in water make-up throughout the USA and international. -

GENERAL APPEARANCE Equally Proficient on Land and in the Water, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever Was Developed Along the Chesapeake

THE AMERICAN CHESAPEAKE CLUB PRESENTS AN ILLUSTRATED GUIDE TO THE CHESAPEAKE BAY RETRIEVER This guide was produced by the American Chesapeake Club to give a broader, more detailed understanding of the breed and its standard for the education of judges, breeders and fanciers. All text in italics is explanatory wording. The cooperation and assistance of members of the ACC and fanciers in the production of this presentation was greatly appreciated. 2018 Illustrated Guide Evaluation Committee - Chair, Betsy Horn Humer - Ron Anderson, Charlene Cordiero, and Linda Harger 2012 Guide Committee - Chair, Dyane Baldwin - Audrey Austin, Jo Ann Colvin, Sally Diess, Nat Horn and Joanne Silver All Rights reserved by the American Chesapeake Club 2012 GENERAL APPEARANCE Equally proficient on land and in the water, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever was developed along the Chesapeake Bay to hunt waterfowl under the most adverse weather and water conditions, often having to break ice during the course of many strenuous multiple retrieves. Frequently the Chesapeake must face wind, tide and long cold swims in its work. 1 The breed’s characteristics are specifically suited to enable the Chesapeake to function with ease, efficiency and endurance. In head, the Chesapeake’s skull is broad and round with medium stop. The jaws should be of sufficient length and strength to carry large game birds with an easy, tender hold. The double coat consists of a short, harsh, wavy outer coat and, a dense fine wooly undercoat containing an abundance of natural oil and is ideally suited for the icy, rugged conditions of weather the Chesapeake often works in. -

The Following Article Is a Write up from the Chesapeake Bay Retriever Relief and Rescue

The following article is a write up from the Chesapeake Bay Retriever Relief and Rescue http://www.cbrrescue.org/articles/dontbuy.htm The article not only profiles what the Chessie is all about, but just as important, what it isn’t. We ask all prospective puppy owners to read over carefully and decide if a Chessie fits their life style. While not for everyone, those who do invite a Chesapeake to share their lives are in for a very rich reward. Although quite lengthy, the article is well worth the read… Don't Buy a Chesapeake Bay Retriever IF Copied and expanded upon an article by Pam Green (©1992), titled "Don’t Buy a Bouvier." Pam writes: I first wrote this article nearly 10 years ago. Since then it has become a classic of Bouvier literature, reprinted many times. Since then I have spent nearly 5 years in Bouvier Rescue, personally rescuing, rehabilitating, and placing 3 or 4 per year and assisting in the placement of others. Very little has needed revision in this new addition.....I give my permission freely to all who wish to reprint and distribute it in hopes of saving innocent Bouviers (Ed. note: we read CBR's here!) from neglect and abandonment by those who should never have acquired them in the first place. Interested in buying a Chesapeake Bay Retriever? You must be or you wouldn't be reading this. You've already heard how marvelous CBRs are. Well, I think you should also hear, before it's too late, that CHESAPEAKE BAY RETRIEVERS ARE NOT THE PERFECT BREED FOR EVERYONE. -

GENERAL APPEARANCE Equally Proficient on Land and in the Water, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever Was Developed Along the Chesapeake

THE AMERICAN CHESAPEAKE CLUB PRESENTS AN ILLUSTRATED GUIDE TO THE CHESAPEAKE BAY RETRIEVER This guide was produced by the American Chesapeake Club to give a broader, more detailed understanding of the breed and its standard for the education of judges, breeders and fanciers. All text in italics is explanatory wording. The cooperation and assistance of members of the ACC and fanciers in the production of this presentation was greatly appreciated . Guide Committee-Dyane Baldwin, Chair- Audrey Austin, Jo Ann Colvin, Sally Diess, Nat Horn & Joanne Silver All Rights reserved by the American Chesapeake Club 2012 GENERAL APPEARANCE Equally proficient on land and in the water, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever was developed along the Chesapeake Bay to hunt waterfowl under the most adverse weather and water conditions, often having to break ice during the course of many strenuous multiple retrieves. Frequently the Chesapeake must face wind, tide and long cold swims in its work. The breed’s characteristics are specifically suited to enable the Chesapeake to function with ease, efficiency and endurance. In head, the Chesapeake’s skull is broad and round with medium stop. The jaws should be of sufficient length and strength to carry large game birds with an easy, tender hold. The double coat consists of a short, harsh, wavy outer coat and a dense fine wooly undercoat containing an abundance of natural oil and is ideally suited for the icy rugged conditions of weather the Chesapeake often works in. In body, the Chesapeake is a strong, well balanced, powerfully built animal of moderate size and medium length in body and leg, deep and wide in chest, the shoulders built with full liberty of movement, and with no tendency to weakness in any feature, particularly the rear. -

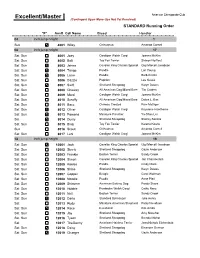

Excellent/Master (Contingent Upon Move-Ups Not Yet Received) STANDARD Running Order

American Chesapeake Club Excellent/Master (Contingent Upon Move-Ups Not Yet Received) STANDARD Running Order "P" Arm# Call Name Breed Handler 04 inch jump height 1 Sun 4001 Wiley Chihuahua Amanda Cornell 08 inch jump height 17 Sat Sun 8001 Joey Cardigan Welsh Corgi Joanna McKim Sat Sun 8002 Bolt Toy Fox Terrier Sharon Norfleet Sat Sun 8003 Jenna Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Gigi Marcell Jacobson Sat Sun 8004 Tango Poodle Lori Young Sat Sun 8005 Lacie Poodle Barb Kraatz Sat Sun 8006 Dazzle Papillon Lee Kusek Sat Sun 8007 Swift Shetland Sheepdog Karyn Dawes Sat Sun 8008 Chewey All American Dog/Mixed Bree Tim Carben Sat Sun 8009 Marzi Cardigan Welsh Corgi Joanna McKim Sat Sun 8010 Scruffy All American Dog/Mixed Bree Debra L. Bax Sat Sun 8011 Bacc Chinese Crested Pam Metzger Sat Sun 8012 Oliver Cardigan Welsh Corgi Kayelene Hawthorne Sat Sun 8013 Pomona Miniature Pinscher Ya-Shan Lei Sat 8014 Dusty Shetland Sheepdog Shelley Bakalis Sat Sun 8015 Bing Toy Fox Terrier Karena Kosco Sun 8016 Scout Chihuahua Amanda Cornell Sat Sun 8017 Luni Cardigan Welsh Corgi Joanna McKim 12 inch jump height 19 Sat Sun 12001 Jack Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Gigi Marcell Jacobson Sat Sun 12002 Steele Shetland Sheepdog Gayle Anderson Sat Sun 12003 Frankie Boston Terrier Sandy Crook Sat Sun 12004 Simon Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Jan Chamberlain Sat Sun 12005 Kaelee Poodle Cindy Mack Sat Sun 12006 Shine Shetland Sheepdog Karyn Dawes Sat Sun 12007 Copper Beagle Carol Waitman Sat Sun 12008 Noodle Poodle Anne Platt Sat Sun 12009 Shimmer American Eskimo Dog Pandy