Characterization of Basigin and the Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CD147) Is Induced by C/Ebpβ and Is Differentially Expressed in ALK+

Laboratory Investigation (2017) 97, 1095–1102 © 2017 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0023-6837/17 EMMPRIN (CD147) is induced by C/EBPβ and is differentially expressed in ALK+ and ALK − anaplastic large-cell lymphoma Janine Schmidt1, Irina Bonzheim1, Julia Steinhilber1, Ivonne A Montes-Mojarro1, Carlos Ortiz-Hidalgo2, Wolfram Klapper3, Falko Fend1 and Leticia Quintanilla-Martínez1 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK+) anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) is characterized by expression of oncogenic ALK fusion proteins due to the translocation t(2;5)(p23;q35) or variants. Although genotypically a T-cell lymphoma, ALK+ ALCL cells frequently show loss of T-cell-specific surface antigens and expression of monocytic markers. C/EBPβ, a transcription factor constitutively overexpressed in ALK+ ALCL cells, has been shown to play an important role in the activation and differentiation of macrophages and is furthermore capable of transdifferentiating B-cell and T-cell progenitors to macrophages in vitro. To analyze the role of C/EBPβ for the unusual phenotype of ALK+ ALCL cells, C/EBPβ was knocked down by RNA interference in two ALK+ ALCL cell lines, and surface antigen expression profiles of these cell lines were generated using a Human Cell Surface Marker Screening Panel (BD Biosciences). Interesting candidate antigens were further analyzed by immunohistochemistry in primary ALCL ALK+ and ALK − cases. Antigen expression profiling revealed marked changes in the expression of the activation markers CD25, CD30, CD98, CD147, and CD227 after C/EBPβ knockdown. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed a strong, membranous CD147 (EMMPRIN) expression in ALK+ ALCL cases. In contrast, ALK − ALCL cases showed a weaker CD147 expression. -

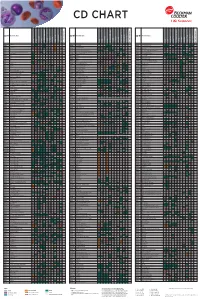

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

No Evidence for Basigin/CD147 As a Direct SARS-Cov-2 Spike

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN No evidence for basigin/CD147 as a direct SARS‑CoV‑2 spike binding receptor Jarrod Shilts 1*, Thomas W. M. Crozier 2, Edward J. D. Greenwood2, Paul J. Lehner 2 & Gavin J. Wright 1,3* The spike protein of SARS‑CoV‑2 is known to enable viral invasion into human cells through direct binding to host receptors including ACE2. An alternate entry receptor for the virus was recently proposed to be basigin/CD147. These early studies have already prompted a clinical trial and multiple published hypotheses speculating on the role of this host receptor in viral infection and pathogenesis. Here, we report that we are unable to fnd evidence supporting the role of basigin as a putative spike binding receptor. Recombinant forms of the SARS‑CoV‑2 spike do not interact with basigin expressed on the surface of human cells, and by using specialized assays tailored to detect receptor interactions as weak or weaker than the proposed basigin‑spike binding, we report no evidence for a direct interaction between the viral spike protein to either of the two common isoforms of basigin. Finally, removing basigin from the surface of human lung epithelial cells by CRISPR/Cas9 results in no change in their susceptibility to SARS‑CoV‑2 infection. Given the pressing need for clarity on which viral targets may lead to promising therapeutics, we present these fndings to allow more informed decisions about the translational relevance of this putative mechanism in the race to understand and treat COVID‑19. Te sudden emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in late 2019 has demanded extensive research be directed to resolve the many uncharted aspects of this previously-unknown virus. -

Development and Validation of a Protein-Based Risk Score for Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Patients with Stable Coronary Heart Disease

Supplementary Online Content Ganz P, Heidecker B, Hveem K, et al. Development and validation of a protein-based risk score for cardiovascular outcomes among patients with stable coronary heart disease. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5951 eTable 1. List of 1130 Proteins Measured by Somalogic’s Modified Aptamer-Based Proteomic Assay eTable 2. Coefficients for Weibull Recalibration Model Applied to 9-Protein Model eFigure 1. Median Protein Levels in Derivation and Validation Cohort eTable 3. Coefficients for the Recalibration Model Applied to Refit Framingham eFigure 2. Calibration Plots for the Refit Framingham Model eTable 4. List of 200 Proteins Associated With the Risk of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 3. Hazard Ratios of Lasso Selected Proteins for Primary End Point of MI, Stroke, Heart Failure, and Death eFigure 4. 9-Protein Prognostic Model Hazard Ratios Adjusted for Framingham Variables eFigure 5. 9-Protein Risk Scores by Event Type This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 Supplemental Material Table of Contents 1 Study Design and Data Processing ......................................................................................................... 3 2 Table of 1130 Proteins Measured .......................................................................................................... 4 3 Variable Selection and Statistical Modeling ........................................................................................ -

Targets to Watch for SARS-Cov-2 and COVID-19

Drugs of the Future 2020, 45(4): 1-6 (Advanced Publication) Copyright © 2020 Clarivate Analytics CCC: 0377-8282/2020 DOI: 10.1358/dof.2020.45.4.3150676 Targets to Watch Taking aim at a fast-moving target: targets to watch for SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 L.A. Sorbera, A.I. Graul and C. Dulsat Clarivate Analytics, Barcelona, Spain Contents six coronaviruses had been known to cause disease in humans: HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-HKU1, Summary ........................................... 1 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Introduction ........................................ 1 and Middle East respiratory virus coronavirus (MERS-CoV). SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 ............................ 1 The first four are endemic locally; they have been associ- Targets ............................................. 2 ated mainly with mild, self-limiting disease, whereas the latter two—both betacoronaviruses—can cause severe References .......................................... 5 illness (1-3). Given the high prevalence and wide distribution of coro- naviruses, their large genetic diversity as well as the fre- Summary quent recombination of their genomes, and increasing Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS- activity at the human–animal interface, these viruses CoV-2) is characterized as a betacoronavirus and recog- represent an ongoing threat to human health (4). This fact nized as the seventh discrete coronavirus species capable of recently became starkly evident, with the emergence and causing human disease. This new coronavirus causes febrile rapid spread of a novel coronavirus, first in mainland China respiratory illness and on March 11, 2020, was character- and now globally. The virus—provisionally designated ized as a global pandemic. Investigators have accelerated 2019-nCoV and later given the official name SARS-CoV-2, the search for a vaccine to prevent infection and for agents due to its similarity to SARS-CoV—was quickly isolated to treat it. -

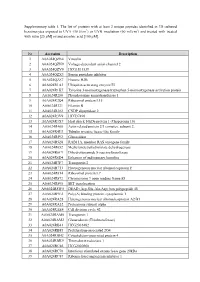

Supplementary Table 1. the List of Proteins with at Least 2 Unique

Supplementary table 1. The list of proteins with at least 2 unique peptides identified in 3D cultured keratinocytes exposed to UVA (30 J/cm2) or UVB irradiation (60 mJ/cm2) and treated with treated with rutin [25 µM] or/and ascorbic acid [100 µM]. Nr Accession Description 1 A0A024QZN4 Vinculin 2 A0A024QZN9 Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 3 A0A024QZV0 HCG1811539 4 A0A024QZX3 Serpin peptidase inhibitor 5 A0A024QZZ7 Histone H2B 6 A0A024R1A3 Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 7 A0A024R1K7 Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein 8 A0A024R280 Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 9 A0A024R2Q4 Ribosomal protein L15 10 A0A024R321 Filamin B 11 A0A024R382 CNDP dipeptidase 2 12 A0A024R3V9 HCG37498 13 A0A024R3X7 Heat shock 10kDa protein 1 (Chaperonin 10) 14 A0A024R408 Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 2, 15 A0A024R4U3 Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family 16 A0A024R592 Glucosidase 17 A0A024R5Z8 RAB11A, member RAS oncogene family 18 A0A024R652 Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 19 A0A024R6C9 Dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase 20 A0A024R6D4 Enhancer of rudimentary homolog 21 A0A024R7F7 Transportin 2 22 A0A024R7T3 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F 23 A0A024R814 Ribosomal protein L7 24 A0A024R872 Chromosome 9 open reading frame 88 25 A0A024R895 SET translocation 26 A0A024R8W0 DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 48 27 A0A024R9E2 Poly(A) binding protein, cytoplasmic 1 28 A0A024RA28 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 29 A0A024RA52 Proteasome subunit alpha 30 A0A024RAE4 Cell division cycle 42 31 -

Erythrocytes Lacking the Langereis Blood Group Protein ABCB6 Are Resistant to the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium Falciparum

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s42003-018-0046-2 OPEN Erythrocytes lacking the Langereis blood group protein ABCB6 are resistant to the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum Elizabeth S. Egan1,2,3, Michael P. Weekes 4,9, Usheer Kanjee1, Jale Manzo1, Ashwin Srinivasan3, 1234567890():,; Christine Lomas-Francis5, Connie Westhoff5, Junko Takahashi6, Mitsunobu Tanaka6, Seishi Watanabe7, Carlo Brugnara 8, Steven P. Gygi4, Yoshihiko Tani6 & Manoj T. Duraisingh1 The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCB6 was recently discovered to encode the Lan- gereis (Lan) blood group antigen. Lan null individuals are asymptomatic, and the function of ABCB6 in mature erythrocytes is not understood. Here, we assessed ABCB6 as a host factor for Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites during erythrocyte invasion. We show that Lan null erythrocytes are highly resistant to invasion by P. falciparum, in a strain-transcendent manner. Although both Lan null and Jr(a-) erythrocytes harbor excess porphyrin, only Lan null erythrocytes exhibit a P. falciparum invasion defect. Further, the zoonotic parasite P. knowlesi invades Lan null and control cells with similar efficiency, suggesting that ABCB6 may mediate P. falciparum invasion through species-specific molecular interactions. Using tandem mass tag-based proteomics, we find that the only consistent difference in membrane proteins between Lan null and control cells is absence of ABCB6. Our results demonstrate that a newly identified naturally occurring blood group variant is associated with resistance to Plasmodium falciparum. 1 Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston 02115 MA, USA. -

COVID-19, Renin-Angiotensin System and Endothelial Dysfunction

cells Review COVID-19, Renin-Angiotensin System and Endothelial Dysfunction Razie Amraei * and Nader Rahimi * Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Boston University Medical Campus, Boston, MA 02118, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.A.); [email protected] (N.R.); Tel.: +1-617-638-5011 (N.R.); Fax: +1-617-414-7914 (N.R.) Received: 3 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 9 July 2020 Abstract: The newly emergent novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, which is caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus, has posed a serious threat to global public health and caused worldwide social and economic breakdown. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is expressed in human vascular endothelium, respiratory epithelium, and other cell types, and is thought to be a primary mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 entry and infection. In physiological condition, ACE2 via its carboxypeptidase activity generates angiotensin fragments (Ang 1–9 and Ang 1–7), and plays an essential role in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which is a critical regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis. SARS-CoV-2 via its surface spike glycoprotein interacts with ACE2 and invades the host cells. Once inside the host cells, SARS-CoV-2 induces acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), stimulates immune response (i.e., cytokine storm) and vascular damage. SARS-CoV-2 induced endothelial cell injury could exacerbate endothelial dysfunction, which is a hallmark of aging, hypertension, and obesity, leading to further complications. The pathophysiology of endothelial dysfunction and injury offers insights into COVID-19 associated mortality. Here we reviewed the molecular basis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the roles of ACE2, RAS signaling, and a possible link between the pre-existing endothelial dysfunction and SARS-CoV-2 induced endothelial injury in COVID-19 associated mortality. -

S41467-019-11790-W.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11790-w OPEN Genetic manipulation of cell line derived reticulocytes enables dissection of host malaria invasion requirements Timothy J. Satchwell 1,2,3,5, Katherine E. Wright 4,5, Katy L. Haydn-Smith1,2,3, Fernando Sánchez-Román Terán4, Pedro L. Moura 1, Joseph Hawksworth1, Jan Frayne1,2, Ashley M. Toye 1,2,3 & Jake Baum 4 1234567890():,; Investigating the role that host erythrocyte proteins play in malaria infection is hampered by the genetic intractability of this anucleate cell. Here we report that reticulocytes derived through in vitro differentiation of an enucleation-competent immortalized erythroblast cell line (BEL-A) support both successful invasion and intracellular development of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Using CRISPR-mediated gene knockout and subsequent complementation, we validate an essential role for the erythrocyte receptor basigin in P. falciparum invasion and demonstrate rescue of invasive susceptibility by receptor re- expression. Successful invasion of reticulocytes complemented with a truncated mutant excludes a functional role for the basigin cytoplasmic domain during invasion. Contrastingly, knockout of cyclophilin B, reported to participate in invasion and interact with basigin, did not impact invasive susceptibility of reticulocytes. These data establish the use of reticulocytes derived from immortalized erythroblasts as a powerful model system to explore hypotheses regarding host receptor requirements for P. falciparum invasion. 1 School of Biochemistry, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 2 NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. 3 Bristol Institute for Transfusion Sciences, National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT), Bristol, UK. 4 Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom. -

The E-Selectin Ligand Basigin/CD147 Is Responsible for Neutrophil Recruitment in Renal Ischemia/ Reperfusion

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org The E-Selectin Ligand Basigin/CD147 Is Responsible for Neutrophil Recruitment in Renal Ischemia/ Reperfusion Noritoshi Kato,*† Yukio Yuzawa,† Tomoki Kosugi,*† Akinori Hobo,*† Waichi Sato,† Yuko Miwa,* Kazuma Sakamoto,* Seiichi Matsuo,† and Kenji Kadomatsu* Departments of *Biochemistry and †Nephrology, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan ABSTRACT E-selectin and its ligands are essential for extravasation of leukocytes in inflammation. Here, we report that basigin (Bsg)/CD147 is a ligand for E-selectin that promotes renal inflammation in ischemia/ Ϫ Ϫ reperfusion. Compared with wild-type mice, Bsg-deficient (Bsg / ) mice demonstrated striking suppres- sion of neutrophil infiltration in the kidney after renal ischemia/reperfusion. Although E-selectin expres- Ϫ Ϫ sion increased similarly between the two genotypes, Bsg / mice exhibited less renal damage, suggesting that Bsg on neutrophils contribute to renal injury in this model. Neutrophils expressed Bsg Ϫ Ϫ with N-linked polylactosamine chains and Bsg / neutrophils showed reduced binding to E-selectin. Bsg isolated from HL-60 cells bound to E-selectin, and tunicamycin treatment to abolish N-linked glycans Ϫ Ϫ from Bsg abrogated this binding. Furthermore, Bsg / neutrophils exhibited reduced E-selectin-depen- dent adherence to human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro. Injection of labeled neutrophils into Ϫ Ϫ mice showed that Bsg / neutrophils were less readily recruited to the kidney after renal ischemia/ ϩ ϩ reperfusion than Bsg / neutrophils, regardless of the recipient’s genotype. Taken together, these results indicate that Bsg is a physiologic ligand for E-selectin that plays a critical role in the renal damage induced by ischemia/reperfusion. -

Cancer-Related Issues of CD147

CANCER GENOMICS & PROTEOMICS 7: 157-170 (2010) Review Cancer-related Issues of CD147 ULRICH H. WEIDLE1, WERNER SCHEUER1, DANIELA EGGLE1, STEFAN KLOSTERMANN1 and HANNES STOCKINGER2 1Roche Diagnostics, Division Pharma, D-82377 Penzberg, Germany; 2Molecular Immunology Unit, Institute for Hygiene and Applied Immunology, Center for Pathophysiology, Infectiology and Immunology, Medical University of Vienna, Austria Abstract. CD147 is involved in many physiological functions, cd147–/– mice. These animals are defective in matrix such as lymphocyte responsiveness, spermatogenesis, metalloproteinase (MMP) regulation, spermatogenesis, implantation, fertilization and neurological functions at early lymphocyte responsiveness and neurological functions at the stages of development. Here we specifically review the role of early stages of development. Such female mice are infertile CD147 in cancer. We focus on the following aspects: due to failure of implantation and fertilization (5). CD147 is expression of CD147 in malignant versus normal tissues and involved in the transport of the MCT-1 and MCT-3 to the its possible impact on prognosis, interaction of tumor cell- plasma membrane since reduced accumulation of these expressed CD147 with stroma cells and induction of matrix transporters has been observed in the retina of cd147 knock- metalloproteinases, as well as the role of CD147 in tumor out mice. A functional role of CD147 in cell adhesion is angiogenesis. The function of CD147 in supercomplexes with supported by its involvement in the blood-brain barrier and monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) and amino acid its interactions with integrins. CD147 has been implicated in transporters such as CD98hc and large neutral amino acid many pathological processes, such as rheumatoid arthritis, transporter 1 (LAT1), as well as the functional contribution of experimental lung injury, atherosclerosis, chronic liver CD147 in complexes with caveolin-1 and integrins, is disease induced by hepatitis C virus, ischemic myocardial discussed.