Holloway Final Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network

BET Networks Delivers More African Americans Each Week Than Any Other Cable Network BET.com is a Multi-Platform Mega Star, Setting Trends Worldwide with over 6 Billion Multi-Screen Fan Impressions BET Networks Announces More Hours of Original Programming Than Ever Before Centric, the First Network Designed for Black Women, is One of the Fastest Growing Ad - Supported Cable Networks among Women NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- BET Networks announced its upcoming programming schedule for BET and Centric at its annual Upfront presentation. BET Networks' 2015 slate features more original programming hours than ever before in the history of the network, anchored by high quality scripted and reality shows, star studded tentpoles and original movies that reflect and celebrate the lives of African American adults. BET Networks is not just the #1 network for African Americans, it's an experience across every screen, delivering more African Americans each week than any other cable network. African American viewers continue to seek BET first and it consistently ranks as a top 20 network among total audiences. "Black consumers experience BET Networks differently than any other network because of our 35 years of history, tremendous experience and insights. We continue to give our viewers what they want - high quality content that respects, reflects and elevates them." said Debra Lee, Chairman and CEO, BET Networks. "With more hours of original programming than ever before, our new shows coupled with our returning hits like "Being Mary Jane" and "Nellyville" make our original slate stronger than ever." "Our brand has always been a trailblazer with our content trending, influencing and leading the culture. -

“Being Mary Jane” on USO Tour to Naval Base San Diego Richard Roundtree, B.J

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: February 19, 2015 Oname Thompson (703) 908-6481 office [email protected] Stars Celebrate the Season Two Return of BET’s “Being Mary Jane” On USO Tour to Naval Base San Diego Richard Roundtree, B.J. Britt and Aaron Spears visit with sailors and their families, and go on tour of installation ARLINGTON, VA. (February 19, 2015) – BET Networks has joined forces with the USO once again, this time treating Naval Base San Diego with a USO visit on Feb. 17 featuring stars from their number one rated television show “Being Mary Jane,” to include actors Richard Roundtree, B.J. Britt and Aaron Spears. On a mission to help the USO make more great #USOMoments in 2015, the group spent the entire day with sailors and their families, and even took time out to learn about the base’s important mission and extensive fleet of Navy ships. **USO photo link below** DETAILS: Roundtree, Britt and Spears kicked off their USO visit with a meet & greet with sailors and their families at the Waterfront Recreation Center, followed by a lunch on base. The group then went on a tour of Naval Base San Diego, where they learned about the base’s mission and operations, and viewed various ship platforms. Roundtree, Britt and Spears join a growing list of famous faces who have participated in USO tours and worked closely with BET over the years. Among other BET stars (both past and present) who have volunteered with the USO to visit and/or entertain troops are Nick Cannon (“Real Husbands of Hollywood”), Keyshia Cole (“Keyshia Cole: All In”) and Rocsi Diaz (“106 & Park”). -

Bay Minette Man Charged with Murder

Serving the greater NORTH, CENTRAL AND SOUTH BALDWIN communities Local artist’s debut album coming in February PAGE 7 Pick an activity for your family today The Onlooker PAGE 32 Local man FEBRUARY 1, 2017 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ charged in boy’s Bay Minette man charged with murder Robertsdale woman’s ered in his vehicle the death of Adell Darlene Rawl- The witness advised Foley PD whipping at a business in ins of Robertsdale. that there was blood coming from body found in car at Foley. On Thursday, the Baldwin the rear of the vehicle. Foley Po- By JOHN UNDERWOOD a business in Foley According to a County Major Crimes Unit was lice responded and found the ve- [email protected] release issued Fri- requested to respond to Highway hicle in the parking lot of Hoods day by the Baldwin 59 in Foley to a possible homi- Discount Home Center at 1918 N. STAFF REPORT BAY MINETTE — County Sheriff’s cide. At approximately 6:10 p.m. McKenzie St. A Bay Minette man CORSON Department in- Foley Police received a call from As officers approached the FOLEY — A Bay Minette man is facing torture/ vestigations com- a witness that was following a vehicle they observed the driver is being charged with murder willful abuse of a mand, Christopher Paul Corson, small white SUV south bound on was covered in blood and upon in the death of a Robertsdale child charges after 36, of Dyas Court in Bay Minette Highway 59 from the Foley Beach further inspection of the vehicle woman after her body was discov- Bay Minette police is being charged with murder in Express. -

An Analysis of Attitudes and Values Via BET Programming Past and Present

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 3-2015 Value Driven: An Analysis of Attitudes and Values Via BET Programming Past and Present Sasha M. Rice California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rice, Sasha M., "Value Driven: An Analysis of Attitudes and Values Via BET Programming Past and Present" (2015). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 135. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUE DRIVEN: AN ANALYSIS OF ATTITUDES AND VALUES VIA BLACK ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISON (BET) PROGRAMMING PAST AND PRESENT ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Communication Studies ______________________ by Sasha Marc Rice March 2015 VALUE DRIVEN: AN ANALYSIS OF ATTITUDES AND VALUES VIA BLACK ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION (BET) PROGRAMMING PAST AND PRESENT ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino ______________________ by Sasha Marc Rice March 2015 Approved by: Mary Fong, Committee Chair, Communication Studies Rueyling Chuang, Committee Member Eric Newman, Committee Member Copyright 2009 Sasha Marc Rice ABSTRACT This paper explores the general attitudes of African Americans towards the programming disseminated on the Black Entertainment Television (BET) network past and present (pre-Viacom/post-Viacom). -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

A Choice to Change the World I -01 A î ÜL © ELMAN L_ I C AT I O N Intellectual Framewori ie Freethinker Feb/March 2014 ■ 4 •»Al ■h ABOUT Want to Advertise in The BluePrint: Chief Editors The BluePrint? Ko Bragg, Editor-in-Chief Ayanna Runcie, Managing Editor (abroad) If you are interested in advertising, Erin GlOSter, Interim Managing Editor please send your advertisement with the Jasmine Ellis, Associate Editor appropriate print specifications and a check Raquel Rainey, Copy Editor payable to Spelman College: The Blue Print to Business Team Marli Crowe, Advertising Manager [email protected]. Danyelle Carter, Public Relations Manager You may also mail your advertisements to: Section Editors The Blue Print- A Spelman Spotlight Production Houston Scott, Fashion & Beauty Analisa Wade, Arts & Entertainment Spelman College Alexis Dulan, Domestic & International News 350 Spelman Lane SW Courtney King, Campus Life Campus Box 1577 Erin Gloster, Campus Life Atlanta, GA 30314 Tyler Lee, Business & Finance Taylor Curry, Food & Drink Adrian Thomas, Opinions If you have any questions, Jordan Daniels, Religion & spiritual Life please contact Marli Crowe at (480) 277-4387 Lydia Hayes, Health & Wellness or Campus Advisor the Office of the Dean of Students at (404) 270-5133. Kimberly M. Ferguson, Student Affairs Thanks to all of our contributing, staff, and featured writers. How to Reach Us 350 Spelman Ln SW Atlanta, GA 30314 Entail: [email protected] The BluePrint: College, Mission Statment It is the mission of The BluePrint to Graphic Design and Printing serve as a profound forum that fortifies Provided by Ashley Eberhardt understanding, unity, and advocacy & Greater Georgia Printers throughout the Spelman and greater AUC Rely on us for ALL community. -

50Womencan Bios

THE COHORT BIOS THE COHORT Aisling Chin-Yee Aisling Chin-Yee is an award winning producer, writer, and director based in Montreal, Canada. Working closely with writers and directors with unique, unapologetic visions in both feature films and documentaries from around the world. She began her production career as an associate producer at the National Film Board of Canada in 2006, joined Prospector Films as producer and director in 2010. Aisling founded Fluent Films in early 2016. She co-created, alongside actor Mia Kirshner, #AfterMeToo, a symposium, series and report that analyzes the issue of sexual misconduct in the entertainment industry. She produced the short films, Three Mothers (2008), The Color of Beauty (2010) Sorry, Rabbi (2011). In 2013 she produced the award winning feature film, Rhymes for Young Ghouls, which was a TIFF Top 10 film, and won Best Director at the Vancouver International Film Festival, as well as the award-winning feature documentary Last Woman Standing that same year. 2014 marked her year as writer and director with the short film, Sound Asleep that Canada brought to the Cannes Film Market and premiered at Lucerne International Film Festival. In 2015, she directed the multi-award winning documentary Synesthesia and produced the gritty urban drama, The Saver that released in Spring 2016.Aisling produced the US series and feature, Lost Generation, with LA based company New Form Digital starring Katie Findlay (How to Get Away with Murder, Man Seeking Woman), Callum Worthy, and Melissa O'Neil, that hit VOD platforms autumn 2016 across North America. With Prospector Films, she produced the documentary Inside these Walls which released on CBC October 2016. -

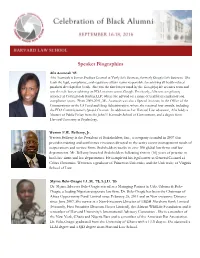

Speaker Biographies

Speaker Biographies Afia Asamoah ’05 Afia Asamoah is Senior Product Counsel at Verily Life Sciences, formerly Google Life Sciences. She leads the legal, compliance, and regulatory affairs teams responsible for advising all health-related products developed at Verily. She was the first lawyer hired by the Google[x] life sciences team and was the sole lawyer advising on FDA matters across Google. Previously, Afia was a regulatory attorney at Covington & Burling LLP, where she advised on a range of healthcare regulatory and compliance issues. From 2009-2011, Ms. Asamoah was also a Special Assistant in the Office of the Commissioner at the US Food and Drug Administration, where she received four awards, including the FDA Commissioner’s Special Citation. In addition to her Harvard Law education, Afia holds a Masters of Public Policy from the John F. Kennedy School of Government, and a degree from Harvard University in Psychology. Werten F.W. Bellamy, Jr. Werten Bellamy is the President of Stakeholders, Inc., a company founded in 2007 that provides training and conference resources directed to the active career management needs of corporations and service firms. Stakeholders works in over 100 global law firms and law departments. Mr. Bellamy launched Stakeholders following sixteen (16) years of practice in both law firms and law departments. He completed his legal career as General Counsel of Celera Genomics. Werten is a graduate of Princeton University and the University of Virginia School of Law. Myma Belo-Osagie LL.M. ’78, S.J.D. ’85 Dr. Myma Adwowa Belo-Osagie served as a Managing Partner in Udo, Udoma & Belo- Osagie, a leading Nigerian corporate law firm. -

AA-Postscript.Qxp:Layout 1

LIFESTYLE36 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2014 Awards ‘12 Years a Slave’ wins big at NAACP Image Awards List of winners of the 45th annual Image Awards FILM l Motion picture: “12 Years A Slave.” l Actor in a motion picture: Forest Whitaker, “Lee Daniels’ The Butler.” l Actress in a motion picture: Angela Bassett, “Black Nativity.” l Supporting actor in a motion picture: David Oyelowo, “Lee Daniels’ The Butler.” l Supporting actress in a motion picture: Lupita Nyong’o, “12 Years A Slave” l Directing in a motion picture: Steve McQueen, “12 Years A Slave.” l Writing in a motion picture: John Ridley, “12 Years A Slave.” l Independent motion picture: “Fruitvale Station.” l International motion picture: “War Witch.” l Documentary: “Free Angela and All Political Prisoners.” Lupita Nyong’o accepts the award for outstanding support- Forest Whitaker poses in the press room David Oyelowo accepts the award for outstand- ing actress in a motion picture for “12 Years a Slave” at the with the chairman award and the award ing supporting actor in a motion picture for “Lee TELEVISION: 45th NAACP Image Awards. —AP Photos for outstanding actor in a motion picture Daniels’ The Butler”. l Drama series: “Scandal.” for “Lee Daniels’ The Butler”. l Actor in a drama series: LL Cool J, “NCIS: Los Angeles.” l Years a Slave” swept the Actress in a drama series: Kerry Washington, film categories at the “Scandal.” “12NAACP Image Awards l Supporting actor in a drama series: Joe Morton, with four wins. The historical epic’s prizes “Scandal.” at Saturday’s 45th annual ceremony hon- l Supporting actress in a drama series: Taraji P. -

BET Networks Is Harnessing the Power of More to Deliver More Premium Original Programming and Unforgettable Moments Across More Platforms in 2016-2017 Fiscal Year

April 20, 2016 BET Networks is Harnessing the Power of More to Deliver More Premium Original Programming and Unforgettable Moments across More Platforms in 2016-2017 Fiscal Year BET Networks Reimagines and Evolves Its Entire Digital Ecosystem BET Networks Delivers More African American Viewers Than Any Other Cable Network BET Networks is the #1 Ad-Supported Multiplatform Destination for African American Viewers BET Networks is the #1 Cable Growth Network Q1 2016 among All Adults 18-49 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- BET Networks announced today its upcoming programming schedule for BET and Centric at its annual Upfront presentation. From fresh original scripted series and provocative reality series, to powerful movies and returning network hits, BET Networks' 2016 slate features more premium original programming across more platforms than ever before. Telecasting for more than 35 years, and currently available in over 85 million US households, and over 35 million homes across the globe, BET Networks prevails as the #1 cable network for African American viewers. Adding to the brand environment with Centric, BET Jams and BET Soul, BET Networks delivers more channels and premium original content to drive authentic viewer engagement and amplify brand love. With more platforms and authentic content energizing viewers, not only does BET reach more African American viewers than any other cable network, but its viewers also tune in longer than its competitive set. This fierce brand loyalty has already translated into the networks' year over year growth outpacing all of cable, with BET ranking as the #1 Cable Growth Network in Q1 2016 among ALL Adults P18-49. -

Workshop Speakers & Hands-On Activities

Science Science 1 Dr. Richard Allen Williams is the Founder of the Association of Black Cardiologists, is a cum laude honors graduate of Harvard University. He subsequently attended the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center where he received the M.D. degree in 1962. Dr. Williams was formerly the Head of Cardiology at the West Los Angeles VA Hospital. At present he is a Clinical Professor of Medicine at the UCLA School of Medicine (full Professor), where he has been a faculty member for over 40 years. Dr. Williams is a noted author and founder of the Minority Health Institute, which focuses on educational programs to teach doctors about cultural competency, diversity, and healthcare disparities. Dr. Valencia Walker is a neonatologist in Los Angeles, California and is affiliated with multiple hospitals in the area, including UCLA Medical Center and UCLA Medical Center Santa Monica. She received her medical degree from Emory University School of Medicine and has been in practice almost 15 years. She is one of 20 doctors at UCLA Medical Center and one of 15 at UCLA Medical Center Santa Monica who specialize in Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. Medical Board Certifications: Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine, American Board of Pediatrics, 2008, 2015, Fellowship: Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, 2003-2006, UCLA School of Medicine, 2011-2013, Residency: Pediatrics, University of Tennessee College of Medicine, 2000-2001 & 2001-2003, Emory University School of Medicine, MD, 2000. Science 2 Kai A. Littlejohn received her B.S. degree in Chemical Engineering from Tuskegee University in 2018. Following graduation, she worked at the U.S. -

Family Matters

COVER STORY..............................................................2 The Sentinel FEATURE STORY...........................................................3 SPORTS.....................................................................4 MOVIES............................................................8 - 22 WORD SEARCH/ LATE LAUGHS/ CABLE GUIDE....................10 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS..................................................12 SUDOKU..................................................................13 tvweek STARS ON SCREEN/Q&A..............................................23 January 29 - February 4, 2017 Family Milo Ventimiglia and Mandy matters Moore star in “This Is Us” Ewing Brothers 2 x 3 ad www.Since1853.com Averaging more than nine million viewers per episode, “This Is Us” is barreling through its freshman season, having secured a full-season order just hours after its premiere. Starring Milo Ventimiglia (“Gilmore Girls”) and 630 South Hanover Street Mandy Moore (“A Walk to Remember,” 2002) among its ensemble cast, the series jaunts back and forth between Carlisle•7 17-2 4 3-2421 different time periods as it follows several characters whose lives are intertwined. An episode of “This Is Us” airs Tuesday, Jan. 31, on NBC. Steven A. Ewing, FD, Supervisor, Owner 2 JANUARY 28 CARLISLE SENTINEL cover story out, putting the focus on sec- mon”), the doc who delivered Dan Fogelman’s ‘This Is Us’ is a freshman hit ondary characters and their Kevin and Kate and comes own back stories. Here, in par- back into the picture a decade By Jacqueline Spendlove ticular, we see more into the or so later. TV Media past of Randall’s birth father, Catch up with “This Is Us” William (Ron Cephas Jones, when an episode of the break- f you’re perusing a list of the “Half Nelson,” 2006), and Dr. K out hit airs Tuesday, Jan. 31, Ibest new shows of fall 2016, (Gerald McRaney, “Simon & Si- on NBC. -

Nena Erb, ACE Editor

Nena Erb, ACE Editor Comedy & Drama Series Include: Insecure* Comedy & Drama Series • HBO Season 3 & 4 Exec Prods: Issa Rae & Prentice Penny • Dir: Various * Primetime Emmy Nomination 2020 – Outstanding Picture Editing For A Comedy Series * ACE Eddie Nomination 2019 - Best Edited Comedy Series for Non-commercial Television Little America Comedy & Drama Anthology • Universal Television • Apple Season 1 Exec Prods: Kumail Nanjiani, Emily Gordon, Alan Yang, Lee Eisenberg & Sian Heder • Dir: Various Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Comedy, Drama & Musical Series Season 3 & 4 CW • CBS Television • Warner Bros. Television Exec Prods: Aline Brosh McKenna, Rachel Bloom, Erin Ehrlich Dir: Various * ACE Eddie Nomination 2020 - Best Edited Comedy Series for commercial Television Jessica Gao Project Comedy • Imagine Entertainment • ABC Pilot Exec Prods: Jessica Gao, Larry Wilmore, Samie Folvie, Brian Grazer, Ron Howard • Director: Jude Weng Halfway Dark Comedy • HBO Access Presentation Exec Prods: Kelly Edwards & Kimberley Browning Co-Prod: Megan Murphy • Director: Carey Williams Being Mary Jane Drama Series • BET • Will Packer Productions Season 4 & 5 Exec Prods: Will Packer & Erica Shelton Kodish • Dir: Various Zoe Ever After Romantic Comedy • BET • Martin Chase Productions Pilot & Season 1 Exec Prods: Erica Montolfo-Bura, Deborah Martin Chase, Danny Rose Directors: Stan Lathan & Henry Chan Real Husbands of Hollywood Scripted Comedy/Mockumentary • BET • 3 Arts Seasons 2 through 5 Exec Prods: Kevin Hart, Ralph Farquhar, Tim Gibbons Dir: Stan Lathan, Chris Robinson,