Chess Players' Performance Beyond 64 Squares: a Case Study on the Limitations of Cognitive Abilities Transfer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Knockout: Adams, Howell, Jones & Mcshane

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release BRITISH KNOCKOUT: ADAMS, HOWELL, JONES & MCSHANE INTO SEMIS England top 4 Mickey Adams, David Howell, Gawain Jones and Luke McShane all negotiate their way through a tough quarter-final stage to qualify for the British Knockout Championship semi-finals. David Howell triumphs eventually over IM Ravi Haria in a rapid playoff, despite almost coming to grief in the first Classical game. Semi-Finals pit Adams vs McShane and Howell vs Jones. Live coverage of the Semi-Final matches, starting Tuesday at 11:00 UTC, is available on the London Chess Classic website. LONDON (December 10, 2018) – Despite valiant efforts from the underdogs in the British Knockout, England Olympiad team members Mickey Adams, David Howell, Gawain Jones and Luke McShane all managed to win their Quarter-Final matches – although not without a struggle. Qtr Fina1 1 1 2 3 4 A Simon Williams 2466 ½ 0 - - - ½ Mickey Adams 2706 ½ 1 - - - 1½ Qtr Fina1 2 1 2 3 4 A David Howell 2697 ½ ½ 1 1 - 3 Ravi Haria 2436 ½ ½ 0 0 - 1 Qtr Fina1 3 1 2 3 4 A Gawain Jones 2683 1 ½ - - - 1½ Alan Merry 2429 0 ½ - - - ½ Qtr Fina1 4 1 2 3 4 A Jonathan Hawkins 2579 ½ 0 - - - ½ Luke McShane 2667 ½ 1 - - - 1½ David Howell had the closest shave of all the top seeds, only managing to qualify for the Semi-Finals after winning a nail-biting playoff match 2-0 against IM Ravi Haria. Elsewhere, Mickey Adams enjoyed a convincing victory in Game 2 of his match, after putting GM Simon Williams’s central king position under pressure in a double-edged Sicilian Richter-Rauzer. -

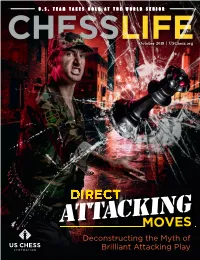

Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW!

U.S. TEAM TAKES GOLD AT THE WORLD SENIOR October 2018 | USChess.org Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW! GM Alexander Kalinin traces Fabiano Caruana’s career, analyses the role of his various trainers, explains the development of his playing style and points out what you can learn from his best games. With #!"$ paperback | 208 pages | $19.95 | from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDs at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum - Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked ADULT $ SCHOLASTIC $ 1 YEAR 49 1 YEAR 25 PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP In addition to these two MEMBER BENEFITS premium categories, US Chess has many •Rated Play for the US Chess community other categories and multi-year memberships •Print and digital copies of Chess Life (or Chess Life Kids) to suit your needs. For all of your options, •Promotional discounts on chess books and equipment see new.uschess.org/join- uschess/ or call •Helping US Chess grow the game 1-800-903-8723, option 4. www.uschess.org 1 Main office: Crossville, TN (931) 787-1234 Press and Communications Inquiries: [email protected] Advertising inquiries: (931) 787-1234, ext. 123 Tournament Life Announcements (TLAs): All TLAs should be e-mailed to [email protected] or sent to P.O. Box 3967, Crossville, TN 38557-3967 Letters to the editor: Please submit to [email protected] Receiving Chess Life: To receive Chess Life as a Premium Member, join US Chess, or enter a US Chess tournament, go to uschess.org or call 1-800-903-USCF (8723) Change of address: Please send to [email protected] Other inquiries: [email protected], (931) 787-1234, fax (931) 787-1200 US CHESS US CHESS STAFF EXECUTIVE Executive Director, Carol Meyer ext. -

Hull 2016 Grandmaster Challenge

Hull 2016 Grandmaster Challenge Sunday June 5th 2016 saw the third Hull Grandmaster Challenge following two successful events in 2014 and 2015 against Gawain Jones and David Howell respectively. The current world number 69 and second highest English ranked player in the world, Luke McShane came to Hull. The venue was the excellent Elizabethan Suite at the Mecure Royal Hull Hotel. The day followed the same format as previously – a blitz in the morning and then a full simultaneous in the afternoon. In the morning a blitz session Luke took on seven players (with grades ranging from 192 to 132) with just 60 seconds on his clock to five minutes on ‘ours’. A 7-0 whitewash to Luke, although he only just managed to defeat Eric Gardiner (182) with one second remaining on his clock! Ryan Burgin (192) had a n excellent position, but then lost twice on the same move (once on time and once for an illegal move – is this a record!). After three years of this blitz format the scores are: Grandmasters 18.5, Hull 1.5. Something doesn’t quite seem right here!! GM Gawain Jones 6/6 = 100% GM David Howell 5.5/7 = 79% GM Luke McShane 7/7 = 100% The afternoon simultaneous was formally opened by the Lord Mayor of Kingston upon Hull and Admiral of the Humber, Cllr Sean Chaytor who made the first move on the top board (d4). There were 31 opponents with players from Harrogate, Leeds and Sheffield supplementing local players. The first player to lose ‘fell’ after 85 minutes. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Starting Out: the Sicilian JOHN EMMS

starting out: the sicilian JOHN EMMS EVERYMAN CHESS Everyman Publishers pic www.everymanbooks.com First published 2002 by Everyman Publishers pIc, formerly Cadogan Books pIc, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD Copyright © 2002 John Emms Reprinted 2002 The right of John Emms to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 857442490 Distributed in North America by The Globe Pequot Press, P.O Box 480, 246 Goose Lane, Guilford, CT 06437·0480. All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD tel: 020 7539 7600 fax: 020 7379 4060 email: [email protected] website: www.everymanbooks.com EVERYMAN CHESS SERIES (formerly Cadogan Chess) Chief Advisor: Garry Kasparov Commissioning editor: Byron Jacobs Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton Production by Book Production Services Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire Everyman Chess Starting Out Opening Guides: 1857442342 Starting Out: The King's Indian Joe Gallagher 1857442296 -

My Best Move

MY BEST MOVE Fred Wilson Noted Chess Bookseller Became a Master at age 71 PHOTO CREDIT: COURTESY OF SUBJECT MY BEST MOVE IS TWOFOLD, CONSISTING of two moves made almost exactly 50 years apart; the first was played over the board while the second, and most important, was made in “real life.” My first “best move” was played in the fifth round of the Manhattan Open on August 6th, 1967. I was 21 years old, already married with two kids, rated 2049, and still trying to “make master”—a quest that began in 1961 at the New York City Junior Championship, where I’d scored only 3-3, but did win the “best-played game” prize awarded by GM Bill Lombardy, and got my first US Chess rating (1704). After four rounds I had three points, having lost to GM Nicolas Rossolimo in the second round (in a good game published I was used to dealing with tactical both by The New York Times and Chess Review). And now I faced future-IM Walter Shipman and surprises and I handle time pressure well. played what is still probably my best game ever: “ ” MY BEST GAME EVER Bc5 Bxc5 29. bxc5 Qxc5 30. d6 Qc8 31. But here being a good chessplayer helped. Fred Wilson d7 Qd8 32. Nd4 Rxf2+ (The best try.) 33. I was used to dealing with tactical surprises Walter Shipman Kxf2 Qxd7 34. Nf3 Qe7 35. Rd5 g4 36. and I handle time pressure well. I immediately Manhattan Open, 1967 (5) Red1! Qa3 37. Rd8+ Kf7 38. -

Minnesota. Curt Brasket, Ronald Lh50n and Roman Filipovich Each Scored 4Y2

MARCH 1967 YOUNG SCHOLARS 65 CENTS Sub,crlptlo" R.te ONE YEAR S7 .50 • e 789 PAGES: 7 1h by 9 inches. clothbound 111 diagram. 493 idea va riatIons 1704 practical variations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all variations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A. HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion. Dr. Max Euwe. Ernest Gruenfeld. Hans Kmoch. and many other noted authorities This latest and immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, ex plains in encyclopedic detail the fi ne points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid-position with the query : Wha t happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key position. Then fol BIB LI OPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by "Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print. Practical and Supplementary Variations, well annotated, exemplify the effective possibilities. Each line is appraised: or spacious paging and a ll the +, - = . The large format- 7V:! x 9 inches-is designed fo r ease of read· other appurtenances of exquis_" ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuffling of pages ite book.making combine to between the principal lines and the respective comments. Clear, legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation.identify. make t his t he handsomest of ing diagrams are other plus features. chess books! In addition to all else, this book contains 439 complete games-a golden treQ.$ury in itself! 1- - - -- - - - -- - ----------- - - -- - -- - 1 I Please send me Chess Openings : Theory and Practice at 812.50 I Name . -

Margate Chess Congress (1923, 1935 – 1939)

Margate Chess Congress (1923, 1935 – 1939) Margate is a seaside town and resort in the district of Thanet in Kent, England, on the coast along the North Foreland and contains the areas of Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay and Westbrook. Margate Clock Tower. Oast House Archive Margate, a photochrom print of Margate Harbour in 1897. Wikipedia The chess club at Margate, held five consecutive international tournaments from spring 1935 to spring 1939, three to five of the strongest international masters were invited to play in a round robin with the strongest british players (including Women’s reigning World Championne Vera Menchik, as well as British master players Milner-Barry and Thomas, they were invited in all five editions!), including notable "Reserve sections". Plus a strong Prequel in 1923. Record twice winner is Keres. Capablanca took part three times at Margate, but could never win! Margate tournament history Margate 1923 Kent County Chess Association Congress, Master Tournament (Prequel of the series) 1. Grünfeld, 2.-5. Michell, Alekhine, Muffang, Bogoljubov (8 players, including Réti) http://storiascacchi.altervista.org/storiascacchi/tornei/1900-49/1923margate.htm There was already a today somehow forgotten Grand Tournament at Margate in 1923, Grünfeld won unbeaten and as clear first (four of the eight invited players, namely Alekhine, Bogoljubov, Grünfeld, and Réti, were then top twelve ranked according to chessmetrics). André Muffang from France (IM in 1951) won the blitz competition there ahead of Alekhine! *********************************************************************** Reshevsky playing a simul at age of nine in the year 1920 The New York Times photo archive Margate 1st Easter Congress 1935 1. -

Talent Development & Excellence

October 2012 Talent Development & Excellence Guest Editors: James R. Campbell, Kirsi Tirri, & Seokhee Cho Official Journal of the Editor-in-Chief: Albert Ziegler Associate Editors: Bettina Harder Jiannong Shi Wilma Vialle This journal Talent Development and Excellence is the official scholarly peer reviewed journal of the International Research Association for Talent Development and Excellence (IRATDE). The articles contain original research or theory on talent development, expertise, innovation, or excellence. The Journal is currently published twice annually. All published articles are assessed by a blind refereeing process and reviewed by at least two independent referees. Editors-in-Chief are Prof. Albert Ziegler, University of Erlangen- Nuremberg, Germany, and Prof. Jiannong Shi of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Bejing. Manuscripts can be submitted electronically to either of them or to [email protected]. Editor-in-Chief: Albert Ziegler, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany Associate Editors: Bettina Harder, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany Jiannong Shi, Academy of Sciences, Beijng, China Wilma, Vialle, University of Wollongong, Australia International Advisory Board: Ai-Girl Tan, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore Barbara Schober, University of Vienna, Austria Carmen M. Cretu, University of IASI, Romania Elena Grigorenko, Yale University, USA Hans Gruber, University of Regensburg, Germany Ivan Ferbežer, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia Javier Tourón, University of Navarra, Spain Mantak Yuen, University of Hong Kong, P.R. China Marion Porath, University of British Columbia, Canada Osamah Maajeeni, King Abdul Aziz University, Saudi- Arabia Peter Merrotsy, University of New England, Australia Petri Nokelainen, University of Tampere, Finland Robert Sternberg, Tufts University, USA Wilma Vialle, University of Wollongong, Australia Wolfgang Schneider, University of Würzburg, Germany Impressum: V.i.S.d.P.: Albert Ziegler, St.Veit-Str. -

British Knockout Chess Championship

PRESS RELEASE BRITISH KNOCKOUT CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP John Saunders reports: The 3rd British Knockout Championship takes place alongside the London Chess Classic from 1-9 December 2017, featuring most of the leading grandmasters from the UK plus the winner of the 4NCL Open held over the weekend of 3-5 November in Coventry. Pairings (The first named player has White in Game 1) Quarter Finals 1 Nigel Short v Alan Merry 2 Matthew Sadler v Jonathan Rowson 3 David Howell v Jonathan Hawkins 4 Gawain Jones v Luke McShane Semi Finals 1 Winner Quarter Final 1 v Winner Quarter Final 4 2 Winner Quarter Final 3 v Winner Quarter Final 2 Final Winner Semi Final 2 v Winner Semi Final 1 In the Final the colours will be reversed after the four Standardplay games, so that the winner of Semi Final 2 will have White in Games 1 and 3 (Standardplay) and Black in Games 5 and 7 (Rapid). A draw for colours in each match was performed on Tuesday 28th November at Chess and Bridge under the supervision of Malcolm Pein. Players were seeded based on their rating as at 1 November 2017, with Nigel Short placed ahead of Matthew Sadler based on his greater number of games played. Nigel Short returns as the reigning British Knockout Champion, having defeated Daniel Fernandez, Luke McShane and then David Howell in last year’s competition to claim the first prize of £20,000. Most grandmasters start drifting away from the game in their fifties but Nigel shows no sign of slackening the pace of his globe- trotting chess career. -

British Knockout: First Blood to Gawain Jones, Narrow Escape for David Howell

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release BRITISH KNOCKOUT: FIRST BLOOD TO GAWAIN JONES, NARROW ESCAPE FOR DAVID HOWELL • Gawain Jones becomes the first player in the British KO Quarter-Finals to pull ahead with a smooth victory in Game 1 over IM Alan Merry. • England No. 1 Mickey Adams is held to a draw by Simon Williams in a sharp Queen’s Gambit. • David Howell barely escapes defeat at the hands of IM Ravi Haria after disastrously weakening his kingside defences and being forced to give up the exchange. • Live coverage on the London Chess Classic website continues today in Game 2 of each of the Quarter-Final classical play matches, followed by rapid playoffs and an Armageddon game if necessary. LONDON (December 9, 2018) – After a first round in which GMs John Nunn and Matthew Turner were knocked out, more surprises were in store for the top seeds in the British Knockout on Sunday as Mickey Adams was held to a draw by Simon Williams, while David Howell was lucky to survive a lost position against Ravi Haria. Simon Williams (aka the ‘Ginger GM’) lived up to his reputation as a fearless aggressive player, trying a bold thrust 8. g4 in a Queen’s Gambit Declined. Despite Adams striking back immediately in the centre, Williams was able to steer play into a slightly favourable endgame in which Adams was forced to defend accurately a pawn down to hold the draw. David Howell looked to be cruising to victory two pawns up in a theoretical Catalan, but then blundered, opening up his king in a position where opposite-coloured bishops were a factor. -

NEW ZEALAND CHESS SUPPLIES New Zealand P.O

NEW ZEALAND CHESS SUPPLIES New Zealand P.O. Box 42{190 Wai nuiomata Phone (04)5il-8578 Fax (04)564{578 Email : chess.chesssupply@ xtra.co.nz Chess Mall order and wholeeale stockists ol the wldeet selecton ol modern chees llterature ln Australmla. Chess sets, boards, clocks, statlonery and all playlng equlpmenL Distrlbutors ol all leadlng brands ol chees computors and sotlware. Send S.A.E. for brochure and catalogue (stato your lnterost), OfEcial magazine ofthe New Zealand Chess Federation (Inc.) PLASTIC CHESSMEN'STAU NTON' STYLE . CLU B/TOU RNAMENT STAN DARD (incl GST) 9omm King, solid, exta weighted, wide felt base (ivory & black matt finish) $Za.OO Vol 23 Number 4 August 1997 $3.50 95mm King solid, weighted, lelt base (black & white semi-gloss finish) $17.50 Plastic container with clip tight lid for above sets $4.00 FOLDI NG CHESSBOARDS - CLU B/TOURNAMENT STAN DARD 48O x 48omm thick cardboard (green and lemon) $O.OO 45O x 450 mm thick vinyl (dark brown and otf white) $14.50 VINYL CHESSBOARDS . CLUB/TOU RNAMENT STANDARD 45O x 47O mm roll-up mat type, algebraic symbols at borders to assist move recognition (green and white) $e.oo zl40 x 440mm ssmi-flex and non-folding, algebraic symbols as above (dark brown and off-white) $9.0O cHESS MOVE TTMERS (CLOCKS) Turnier German-made popular windup club clock, brown plastic $0S.00 Standard German-made as above, in imitation wood case $79.00 DGT otficial FIDE digital chess timer $169.00 SAITEK digital game timer $129.00 CLUB AND TOURNAMENT STATIONERY Bundle of 20O loose score sheets, 80 moves and