Simon Property Group, L.P. V. Starbucks Corp., 2017 WL 6452028 (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simon Property Group, Inc

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007 SIMON PROPERTY GROUP, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-14469 04-6268599 (State or other jurisdiction of (Commission File No.) (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 225 West Washington Street Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 (Address of principal executive offices) (ZIP Code) (317) 636-1600 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12 (b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered Common stock, $0.0001 par value New York Stock Exchange 6% Series I Convertible Perpetual Preferred Stock, $0.0001 par value New York Stock Exchange 83⁄8% Series J Cumulative Redeemable Preferred Stock, $0.0001 par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12 (g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer (as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act). Yes ፤ No អ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes អ No ፤ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

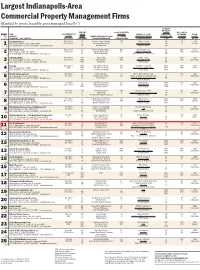

Largest Indianapolis-Area Commercial Property Management Firms (Ranked by Gross Leasable Area Managed Locally (1))

Largest Indianapolis-Area Commercial Property Management Firms (Ranked by gross leasable area managed locally (1)) LOCAL FTE: BROKERS / PERCENT LOCAL PROPERTIES AGENTS HQ LOCATION RANK FIRM GLA MANAGED(1): OFFICE MANAGED HEAD(S) OF LOCAL EMPLOYEES: OF OWNERS: ESTAB. 2009 ADDRESS LOCALLY RETAIL LARGEST INDIANAPOLIS-AREA % OF SPACE OPERATIONS, TITLE(S) PROPERTY MGT. % INDIANA LOCALLY rank TELEPHONE / FAX / WEB SITE NATIONALLY INDUSTRIAL PROPERTIES MANAGED OWNED BY FIRM LOCAL DIRECTOR(S) TOTAL % OTHER HQ CITY Cassidy Turley (2) 29.7 million 30 Keystone at the Crossing, 156 Jeffrey L. Henry, 48 26 1918 One American Square, Suite 1300, 46282 420.0 million 4 Precedent Office Park, 0 managing principal 142 74 St. Louis 1 (317) 634-6363 / fax (317) 639-0504 / cassidyturley.com 66 Castleton Park Timothy J. Michel 199 1 Duke Realty Corp. 28.5 million 20 AllPoints Midwest Bldg. 1, 187 Don Dunbar, EVP; 10 DND 1972 600 E. 96th St., Suite 100, 46240 141.9 million 0 Lebanon Building 12, 87 Charlie E. Podell, SVP 20 DND Indianapolis 2 (317) 808-6000 / fax (317) 808-6770 / dukerealty.com 80 Lebanon Building 2 Ryan Rothacker; Chris Yeakey 400 2 CB Richard Ellis 13.0 million DND Intech Park, DND David L. Reed, 33 DND 1981 101 W. Washington St., Suite 1000E, 46204 11.5 million DND Capital Center, DND managing director 31 DND Los Angeles 3 (317) 269-1000 / fax (317) 637-4404 / cbre.com DND Metropolis Andy Banister 99 4 Prologis 10.5 million DND 715 AirTech Parkway, 55 Elizabeth A. Kauchak, DND DND 1994 8102 Zionsville Road, 46268 DND DND 281 AirTech Parkway, 100 vice president, market officer DND DND Denver 4 (317) 228-6200 / fax (317) 228-6201 / prologis.com 100 558 AirTech Parkway Susan Harvey DND 3 Kite Realty Group Trust 8.8 million 57 Eli Lilly and Co., 75 John A. -

Case 20-13076-BLS Doc 67 Filed 12/07/20 Page 1 of 14

Case 20-13076-BLS Doc 67 Filed 12/07/20 Page 1 of 14 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ------------------------------------------------------------ x : In re: : Chapter 11 : Case No. 20-13076 (BLS) FRANCESCA’S HOLDINGS CORPORATION, : et al.,1 : Joint Administration Requested : Debtors. : Re: D.I. 8 ------------------------------------------------------------ x SUPPLEMENTAL DECLARATION OF SHERYL BETANCE IN SUPPORT OF THE DEBTORS’ APPLICATION FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER AUTHORIZING THE RETENTION AND EMPLOYMENT OF STRETTO AS CLAIMS AND NOTICING AGENT, NUNC PRO TUNC TO THE PETITION DATE Pursuant to 28 U.S.C.§ 1746, I, Sheryl Betance, declare under penalty of perjury that the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge, information, and belief: 1. I am a Senior Managing Director of Corporate Restructuring at Stretto, a chapter 11 administrative services firm with offices at 410 Exchange, Ste. 100, Irvine, CA 92602. Except as otherwise noted, I have personal knowledge of the matters set forth herein, and if called and sworn as a witness, I could and would testify competently thereto. 2. On December 3, 2020, the Debtors filed the Debtors’ Application for Entry of an Order Authorizing the Retention and Employment of Stretto as Claims and Noticing Agent, Nunc Pro Tunc to the Petition Date [D.I. 8] (the “Application”),2 and the Declaration of Sheryl Betance in Support of the Debtors’ Application for Entry of an Order Authorizing the Retention and 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are Francesca’s Holdings Corporation (4704), Francesca’s LLC (2500), Francesca’s Collections, Inc. -

CUMMINS Donna Hovey DISTRIBUTION Vice President, CBRE HEADQUARTERS +1 317 269 1138 DOWNTOWN INDIANAPOLIS AMENITIES [email protected]

CUMMINS Donna Hovey DISTRIBUTION Vice President, CBRE HEADQUARTERS +1 317 269 1138 DOWNTOWN INDIANAPOLIS AMENITIES [email protected] H , O bus lum Co INTERSTATE SKYWALKS 1. Monument Circle ENTERTAINMENT 7 65 & SHOPPING INDIANAPOLIS CULTURAL TRAIL 11th St. 11th St. 2. Bankers Life 7 Fieldhouse 10th St. 10th St. 10th St. 3. Lucas Oil Stadium N 4. Old National Centre Indiana Ave. W E 5. Central Library 9th St. 6. Scottish Rite Cathedral S 5 St. Clair St. 7. Madame Walker Theatre Ctr. 12 8. Indiana History Center 7 Walnut St. 7 9. IN World War Memorial Walnut St. 2 10. City Market 6 Fort Wayne Ave. 7 11. CIRCLE CENTRE MALL North St. North St. Features over 100 retailers including MASS AVE. Central Canal 3 4 Michigan St. Blake St. Michigan St. anchor Carson Pirie Scott . 6 12. MASS AVE RETAIL & ARTS DISTRICT Indiana University 9 Purdue University Vermont St. Indianapolis MAJOR Meridian St. 22 St. Pennsylvania Delaware St. 1. Simon Senate Ave. Capitol Ave. Illinois St. East St. College Ave. West St. West Alabama St. 4 New Jersey St. (IUPUI) Blackford St. 23 University Blvd 12 Headquarters EMPLOYERS New York St. New York St. 2 2. Eli Lilly & Company 8 7 8 4 7. IU Health 1 3. Anthem 5 Ohio St. 8. Rolls-Royce 4. Regions Bank 3 2 5 Central Canal 5 3 1 3 5. M&I Bank White River Indiana 10 State Market St. Capitol 1 6. IUPUI State Park 3 4 5 6 4 5 Pedestrian Bridge Washington St. Parking Garage White River 21 HOTELS 10 9 8 1 7 11 4 1. -

101-115 W. Washington Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Center of It All

WWW.CBRE.COM/PNCC FOR LEASE 101-115 W. WASHINGTON STREET, INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46204 CENTER OF IT ALL FEATURES • New Nexus at PNC now open • Attached to 2,500 covered parking spaces PNC Center is an outstanding • On-site full time leasing and management personnel Class A office building located in • Green Roof Plaza — first of its kind in Indianapolis the ‘center of it all’ in Downtown • Efficient floor layouts with great views of Indy Indianapolis. PNC Center • State-of-the-art facilities including: Access control, Elevators, provides first class amenities Fire and life safety, Mechanical equipment, Restrooms, Security to its tenants including a the new Nexus at PNC featuring a • 16-story atrium tenant lounge, kitchen, vending • Year-round covered connectivity to Circle Centre Mall, Lucas Oil machines, shoe shine, lockers Stadium, the Convention Center, 52 restaurants and 9 hotels and pick-up dry cleaning. • Three restaurants, one bank, one coffee shop and more Mechanical W M Jan. Elevator Lobby EAST TOWER EAST Elevator Lobby Mechanical ATRIUM FLOOR PLAN M Lobby W Elevator Mechanical Mechanical SOUTH TOWER CENTER OF IT ALL MARKET STREET COVERED ACCESS TO: ILLINOIS STREET CIRCLE CENTRE MALL - FOOD COURT Asian Chao Indyo Frozen Yogurt Auntie Anne’s Pretzels Lou’s Cajun Grill A&W Maki of Japan Charley’s Philly Steaks Subway 52 Panera Bread Capital Grille RESTAURANTS Chick Fil-A Taco Bell Fresh Pop’d Villa Pizza Weber Grill La Vitesse Tastings ARTS WASHINGTON STREET GARDEN WEST STREET AVENUE CAPITOL MERIDIAN STREET 6 CIRCLE CENTRE MALL Food Court HOTELS Café Patachou Yard House High Velocity STATE Loughmiller’s PARKING Champps GARAGE Champions Pub & Eatery Osteria Pronto PNC CENTER P.F. -

Oic / Law Enforcement Summit Overview

OPERATIONAL INTELLIGENCE CENTER LAW ENFORCEMENT SUMMIT AUGUST 25 & 26, 2019 INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA OIC / LAW ENFORCEMENT SUMMIT OVERVIEW As part of Simon’s commitment to developing strong public/private relationships with our centers and local law enforcement, we have organized numerous conferences across the country over the past decade. For 2019, we will be hosting a two-day conference in Indianapolis, bringing together law enforcement executives, mall management teams and security directors from 73 premiere properties throughout the Simon Malls, Mills, and Premium Outlets portfolio. In addition, the FBI and DHS will also be participating in this summit as well as key security personnel from a variety of luxury retail brands. On the first evening, a series of live simulations will occur, along with a demonstration of Simon's new Operational Intelligence Center (OIC), followed by a second day of speakers from a variety of backgrounds, discussing relevant challenges facing the retail security realm. As we have in years past, we will be securing sponsors to help us underwrite this event to ensure we have strong attendance from our local law enforcement agencies, stationed all across the US. Sponsors will be encouraged to network with all participants and we will be hosting a Summit Showcase as well where participants will be able to demonstrate products, services and devices utilized at Simon malls or local law enforcement offices each day. The OIC Law Enforcement Summit will take place at The Sheraton Hotel attached to Keystone Fashion -

Shop Simon & Save

SHOP SIMON COURTESY OF & SAVE FOR Present this voucher at Simon Guest Services or Information Center* at any property listed below to receive a Savings Passport filled with special offers at participating retailers and restaurants. ALASKA FLORIDA (CONTINUED) MICHIGAN OHIO VIRGINIA Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall* Silver Sands Premium Outlets® Birch Run Premium Outlets® Aurora Farms Fashion Centre St. Augustine Premium Outlets® at Pentagon City ® ARIZONA Premium Outlets MINNESOTA Cincinnati Leesburg Corner Albertville Premium Outlets® ® ® Arizona Mills® St. Johns Town Center® * Premium Outlets Premium Outlets ® Twin Cities Premium Outlets ® Phoenix Premium Outlets® Tampa Premium Outlets® Potomac Mills Tucson Premium Outlets® Town Center at Boca Raton® OREGON Williamsburg MISSISSIPPI Woodburn Premium Outlets® Gulfport Premium Outlets® ® CALIFORNIA GEORGIA Premium Outlets Camarillo Premium Outlets® Lenox Square® WASHINGTON MISSOURI ® Carlsbad Premium Outlets® Mall of Georgia® PENNSYLVANIA Seattle Premium Outlets Osage Beach The Crossings Desert Hills Premium Outlets® North Georgia Premium Outlets® ® ® Premium Outlets WISCONSIN Fashion Valley Premium Outlets ® St. Louis Premium Outlets Grove City Folsom Premium Outlets® Phipps Plaza Johnson Creek Premium Outlets® ® Gilroy Premium Outlets® Premium Outlets NEVADA ® Las Americas Premium Outlets® HAWAII King of Prussia Mall Pleasant Prairie The Forum Shops at Caesars ® ® Napa Premium Outlets® Waikele Premium Outlets® Philadelphia Premium Outlets Premium Outlets Palace® ® Ross Park Mall Ontario Mills -

Simon Mall Management Lookbook

DEVELOPMENTS 2018 SIMON MALL MANAGEMENT LOOKBOOKBUILDING. THE SHOPPING DESTINATIONS OF THE FUTURE CORPORATE OVERVIEW Redefining our success With a view to the collective success of Simon,® our retail partners, and our neighbors, we continue to redefine and reimagine how people around the world shop. Optimizing results across our global portfolio of preeminent Simon Malls,® Simon Premium Outlets,® and The Mills® is our priority both short and long term. We are also investing in our future. Over the next several years, Simon is committing billions of dollars to both new developments and redevelopment projects that will further diversify and expand the quality and reach of the Simon portfolio. 1 DEVELOPMENTS 2018 At Simon, our commitment to the success of our properties is paramount. We are continuously evaluating our portfolio to enhance the Simon experience, creating state-of-the-art destinations where customers want to shop and socialize. GROUND UP Our strategy focuses on creating superior retail environments and exceptional, world-class destinations for today’s—and future—shoppers. — We’re dedicated to delivering innovative architecture and omnichannel retailing that blends both digital and physical experiences to make shopping more exciting and convenient. — Our priority is the ultimate retail mix, combining best-in-class national and international powerhouses with the newest first-in-market brands and pioneering retail concepts and uses. EXPANSIONS Strategic investments are being made to enhance the market position of our existing assets. — The scope of work includes developing new wings, adding department stores and other key retailers and restaurants, and updating common areas. — Leveraging these investments will further elevate the shopping experience and reinforce Simon as the destination of choice for both shoppers and retailers. -

An Insider's Guide to Notre Dame Law School Notre Dame Law School

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Irish Law: An Insider's Guide Law School Publications Fall 2016 An Insider's Guide to Notre Dame Law School Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/irish_law Recommended Citation Notre Dame Law School, "An Insider's Guide to Notre Dame Law School" (2016). Irish Law: An Insider's Guide. 2. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/irish_law/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Law: An Insider's Guide by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Welcome to Notre Dame Law School! On behalf of the Notre Dame Law School student body, we are thrilled to be among the first to welcome you to the NDLS Community! We know that this is an exciting time for you and – if you are anything like we were just a couple of years ago – you probably have plenty of questions about law school and Notre Dame, whether it’s about academics, professors, student life, or just where to get a good dinner. That’s why we’ve prepared the Guide. This is called an Insider’s Guide because it has been written by students. Over the past year, we’ve updated and revised old sections, compiled and created new ones, and edited and re-edited the whole book in hopes of making your transition to Notre Dame easier. This isn’t a comprehensive guide to everything you need to know to get through law school or thrive in South Bend, but it is a great place to start. -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware

Case 20-13076-BLS Doc 68 Filed 12/07/20 Page 1 of 38 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ------------------------------------------------------------ x In re: : Chapter 11 : FRANCESCA’S HOLDINGS CORPORATION, : Case No. 20-13076 (BLS) 1 et al., : Debtors. : Joint Administration Requested ------------------------------------------------------------ x AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE I, Victoria X. Tran, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the proposed claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On December 4, 2020, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via overnight mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, via facsimile on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C: Certification of Counsel Regarding Emergency Bridge Order (I) Authorizing the Debtors’ Limited Use of Cash Collateral, (II) Authorizing the Continued Use of the Debtors’ Existing Cash Management System and Bank Accounts, and (III) Authorizing Debtors to Maintain Customer Programs and Honor Related Prepetition Obligations on a Limited Basis (Docket No. 37) Emergency Bridge Order (I) Authorizing the Debtors’ Limited Use of Cash Collateral, (II) Authorizing the Continued Use of the Debtors’ Existing Cash Management System and Bank Accounts, and (III) Authorizing Debtors to Maintain Customer Programs and Honor Related Prepetition Obligations on a Limited Basis (Docket No. 39) Notice of (I) Filing of Bankruptcy Petitions and Related Documents and (II) Agenda for Telephonic Hearing on First Day Motions Scheduled for December 8, 2020 at 9:30 a.m. -

Indianapolis, Indiana Indianapolis a Dynamic Downtown

INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA INDIANAPOLIS A DYNAMIC DOWNTOWN Indianapolis delivers a superb blend of sports and culture. — Downtown Indianapolis is rated the #3 downtown in the nation by livability.com. Since 1990, more than $12.4 billion has been invested in the downtown area. Currently, more than 78 projects, consisting of 4328 units, worth $2.9 billion of investment are in the pipeline to be completed between 2017 and 2023. — The largest employers or corporate headquarters include: Simon, Eli Lilly, IUPUI, FedEx, Finish Line, Salesforce, Rolls Royce, and Anthem. — Indianapolis boasts a stellar sports scene with the NBA Indiana Pacers, WNBA Indiana Fever, NFL Indianapolis Colts, MiLB Indianapolis Indians, NASL Indy Eleven, ECHL Indy Fuel, the Greatest Spectacle in Racing the Indianapolis 500, and the NFL Scouting Combine. — Among the many museums are the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA), the Kurt Vonnegut Museum & Library (KVML), the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, and The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. DOWNTOWN MIXED-USE AT ITS BEST Circle Centre Mall is an innovative mixed-use center housing many fine retailers and restaurants. — The mall is anchored by Carson’s, a nine-screen United Artists Theatres, 13 full-service restaurants, the Gannett Company and Indianapolis Star offices, Brown Mackie College, and Simon Youth Academy. — Circle Centre Mall is a popular destination for more than one million daytime workers. — The stunning Indianapolis Artsgarden, located at Circle Centre Mall, hosts more than 250 events throughout the year, including concerts and art exhibitions. — Located in the heart of downtown Indianapolis, this centre offers four full city blocks of shopping and dining. -

IPL COLORING CONTEST Child’S Name: Age

IPL COLORING CONTEST Child’s Name: Age: Phone: Parent’s Name Parent’s Email: Zip Code: *Your information will not be sold or shared with additional partners. Since 1906 2018 INDIANAPOLIS POWER & LIGHT COMPANY COLORING CONTEST ENTRY RULES • The contest runs now through November 13. • One entry per child, ages 3 – 12. • Only Indiana residents may win. • Five finalists will be selected by the judges based on creativity. Of the five finalists, one grand prize winner will be selected. Judging will be done by a panel of representatives from IPL, IBEW 481, College Choice 529, Broadway in Indianapolis, IndyStar, WTHR, Circle Centre and Downtown Indy, Inc. The decision of the judges is final. • The one entry that receives the most votes from the panel will be selected to “flip the switch” on stage at Downtown Indy, Inc.’s Circle of Lights® presented by IBEW 481 on Monument Circle Friday, Nov. 23. • The winner and four additional finalists will each receive $529 deposited into a College Choice 529 direct savings plan and additional gifts courtesy of other Circle of Lights sponsors including Circle Centre Mall, Broadway in Indianapolis, College Choice 529, WTHR-13 and IndyStar. • Finalists will be contacted by Thursday, November 15. • Entries will not be returned and become property of Downtown Indy, Inc. • Some entries will be on public display (without contact information). RETURN IPL COLORING CONTEST ENTRIES TO: IBEW 481, 1828 N. Meridian Street, Suite 205, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 or drop off at Guest Services Circle Centre Mall, 2nd floor PRINT ADDITIONAL COPIES BY DOWNLOADING AT IPLPOWER.COM/COMMUNITY OR WWW.DOWNTOWNINDY.ORG/COLORING.