From the Big Bang to Island Universe: Anatomy of a Collaboration1 by David H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

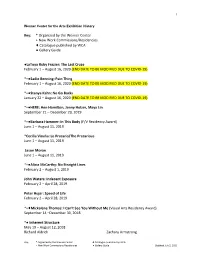

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

Alyson Shotz Education 1991 University of Washington, Seattle

Alyson Shotz Education 1991 University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, MFA 1987 Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island, BFA Solo Exhibitions 2020 Grace Farms, New Canaan, CT (forthcoming) Derek Eller Gallery (forthcoming) 2019 Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC (forthcoming) Hunter Museum of American Art, Chattanooga, TN 2017 Derek Eller Gallery, NYC, Night James Harris Gallery, Seattle, WA 2016 Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA, Plane Weave Locks Gallery, Philadelphia, PA, Weave and Fold Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum, San Antonio, TX , Scattering Screen 2015 Galleri Andersson Sandstrom, Stockholm, Sweden, Light and Shadow Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, Charleston, SC, Force of Nature 2014 Wellin Museum, Hamilton College, Force of Nature Derek Eller Gallery, NYC, Time Lapse Carolina Nitsch Project Room, New York, NY, Topographic Iterations, Tspace, Rhinebeck, NY, Interval 2013 Visual Arts Center, University of Texas, Austin, Invariant Interval Eli and Edythe Broad Museum, Geometry of Light Carolina Nitsch Project Room, New York, NY, Fluid State Derek Eller Gallery, North Room, New York, NY, Chroma 2012 Indianapolis Museum of Art, Fluid State Borås Konstmuseum, Borås, Sweden, Alyson Shotz: Selected Work Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Ecliptic Galeria Vartai, Vilnius, Lithuania. Interval 2011 Espace Louis Vuitton, Tokyo, Geometry of Light Andersson Sandstrøm Gallery, Stockholm and Umeå, Fundamental Forces Carolina Nitsch Contemporary Art, New York, NY, Fundamental Forces Derek -

JOSIAH Mcelheny Born 1966 in Boston

JOSIAH McELHENY Born 1966 in Boston, Massachusetts Lives and works in New York City Solo and Two-Person Exhibitions & Projects 2017 Prismatic Park, Madison Square Park Conservancy, Madison Square Park, New York, NY, June 13 – October 8 (forthcoming) The Crystal Land, White Cube, London, United Kingdom, March 1 – April 16 (forthcoming) 2016 The Ornament Museum, MAK - Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, Austria, April 27 – April 2, 2017 2015 Josiah McElheny: Two Walking Mirrors for the Carpenter Center, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, October 1 – October 25 (brochure) Josiah McElheny: Paintings, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, NY, September 10 – October 24 (catalogue) 2014 Dusty Groove, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL, October 24 – December 6 (catalogue) 2013 Josiah McElheny: Two Clubs at The Arts Club of Chicago, In Collaboration with John Vinci, The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL, September 17 – December 14 Lumber Room, Portland, OR, September 8 – December 7 Josiah McElheny: Towards a Light Club, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH, January 26 – April 7 (catalogue) 2012 The Light Club of Vizcaya: A Women’s Picture, Vizcaya Museum, Miami, FL, November 19, 2012 – March 18, 2013 Interactions of the Abstract Body, White Cube, London, UK, November 16 – January 12, 2013 (catalogue) Josiah McElheny: Some Pictures of the Infinite, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA, June 22 – October 14 (catalogue) Some thoughts about the abstract body, Andrea Rosen Gallery, -

Glenn Ligon Biography

GLENN LIGON BIOGRAPHY Born in Bronx, New York, 1960. Lives and works in New York, NY. Education: Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, New York, NY, 1985 BA, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, 1982 Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI, 1980 Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2021 “Glenn Ligon,” Hauser and Wirth, New York, NY, November 10 – December 23, 2021 “First Contact,” Hauser and Wirth, Zürich, Switzerland, September 17 – December 23, 2021 2019 “Glenn Ligon: In A Year with a Black Moon,” Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, Japan, December 20, 2019 – March 14, 2020 “Des Parisiens Noirs,” Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France, March 26 – July 21, 2019 “Glenn Ligon: Selections from the Marciano Collection,” Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, CA, February 12 – May 12, 2019 “Glenn Ligon: To be a Negro in this country is really never to be looked at.,” Maria & Alberto De La Cruz Art Gallery, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., January 24 – April 7, 2019 “Glenn Ligon: Untitled (America)/Debris Field/Synecdoche/Notes for a Poem on the Third World,” Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA, January 12 – February 17, 2019; catalogue 2018 “Glenn Ligon: Debris Field/Notes for a Poem on the Third World/Soleil Nègre,” Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, France, September 8 – October 4, 2018; catalogue “Glenn Ligon: Tutto poteva, nella poesia, avere una soluzione / In poetry, a solution to everything,” Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples, Italy, April 24 – July 28, 2018 2017 “Glenn Ligon,” Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD, Fall 2017 – 2018 2016 “Glenn Ligon, A Small -

JOSIAH Mcelheny 1966 Born in Boston, MA Lives and Works in New

JOSIAH McELHENY 1966 Born in Boston, MA Lives and works in New York City EDUCATION 1992 Apprentice to Master Glassblower Lino Tagliapietra; various locations: Seattle, Washington, New York, Switzerland 1989 Apprentice to Master Glassblower Jan-Erik Ritzman and Sven-Ake Carlsson, Transjö, Sweden 1988 BFA, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island 1987 European Honors Program, Rhode Island School of Design, Rome, Italy; Study with Master Glassblower Ronald Wilkinson, London, England SOLO AND TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS & PROJECTS 2021 Libraries, James Cohan, New York, NY, April 17 – May 22 2019 Observations at Night, James Cohan, New York, NY, September 6 – October 23 Island Universe, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, February 23 – August 18 2018 Cosmic Love, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL, June 1 – August 4 Island Universe, Moody Center for the Arts, Rice University, Houston, TX, February 2 – June 2 2017 Prismatic Park, Madison Square Park Conservancy, Madison Square Park, New York, NY, June 13 – October 8 The Crystal Land, White Cube, London, United Kingdom, March 1 – April 16 2016 The Ornament Museum, MAK - Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, Austria, April 27 – April 2, 2017 2015 Josiah McElheny: Two Walking Mirrors for the Carpenter Center, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, October 1 – October 25 (brochure) Josiah McElheny: Paintings, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, NY, September 10 October 24 (catalogue) 2014 Dusty Groove, Corbett vs. -

Josiahmcelhenybio2012.Pdf

JOSIAH McELHENY Born 1966 in Boston, Massachusetts Lives and works in New York City Solo and Two-Person Exhibitions & Projects 2012 The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, June 22 – September 23 forthcoming 2011 Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge, Other: Josiah McElheny’s Island Universe, Harvard Arts Museum, Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, MA, October 15 The Bloomberg Commission: Josiah McElheny, Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK, September 7, 2011 – August 12, 2012 Tate Modern Live: Push and Pull, a two-day performance event, with Andrea Geyer, Tate Modern, London, UK, March 19 2010 Crystalline Modernity, Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, Illinois. November 12 2009 Proposals for a Chromatic Modernism, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, New York, September 12 - October 17 A Space for an Island Universe, Museo Nacional Centro De Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain, January 28 - March 20 2008 Island Universe, White Cube, London, United Kingdom. October 14 – November 15, (catalogue) The Light Club of Batavia, Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, Illinois. September Das Lichtklub von Batavia/The Light Club of Batavia, Institut im Glaspavillon, Berlin, Germany. July 5, 6, & 10 The Last Scattering Surface, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle and Rochester Art Center, Seattle, Washington. April 5 – August 17 2007 The 1st at Moderna: The Alpine Cathedral and The City-Crown, Moderna Museet, Stockholm. December 1 - February 17, 2008 Projects 84: Josiah McElheny, Museum of Modern Art, New York. February 12 – April 9 Cosmology, Design and Landscape– Part II, Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, Illinois. June. 2006 Cosmology, Design and Landscape – Part I, Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, Illinois. September 29 – October 28 Modernity 1929–1965, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, New York. -

W I N T E R 2 0

WINTER 2019 Dear Friends, When Jane Stanford dreamed of a museum that would be part of the university named in memory of her son Leland Jr., her vision included a museum that would provide educa- tion to the entire community. Now, nearly 125 years later, the Cantor Arts Center and the Anderson Collection at Stanford University are proud to welcome visitors from the Stanford campus, the Bay Area, and around the world to engaging exhibitions, educational programs, and hands-on family activities that promote new ways of thinking about Photograph by Stacy H. Geiken the visual arts. relationship between art and science evident in Josiah Each fall, it has been our tradition to acknowledge our McElheny’s sparkling sculptures, or watching the innova- community of donors in this publication. I am truly grateful tive live-feed broadcast of Stanford Presidential Visiting to our dedicated donors and members for enabling us to Artist Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS, we hope you’ll find some- fulfill Jane Stanford’s vision. Your support allows us to be a thing here at the Cantor to challenge and engage you. truly 21st-century museum and the hub of critical inquiry With your help, we look forward to the next 125 into the visual arts on campus, by enhancing our collections years, as we continue to uphold Leland Jr.’s legacy and presenting exciting new exhibitions that ask important and Jane Stanford’s vision by providing world-class art questions about the world in which we live. experiences for all. This year, we hope you will take advantage of wonderful programs and opportunities to engage with art in the galleries and to discover something new. -

Josiah Mcelheny CV

Josiah McElheny Born 1966 in Boston, Massachusetts Lives and works in New York Selected Solo Exhibitions & Installations 2019 Josiah McElheny: Observations at Night, James Cohan, New York, NY 2018 Island Universe, Moody Centre for Arts at Rice University, Houston, TX Josiah McElheny: Cosmic Love, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago Josiah McElheny: Island Universe, Moody Center for the Art, Houston, TX 2017 Prismatic Park, Madison Square Park Conservancy, Madison Square Park, New York The Crystal Land, White Cube, London 2016 The Ornament Museum, MAK – Osterreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, Austria 2015 Josiah McElheny: Two Walking Mirrors for the Carpenter Center, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, Cambridge Josiah McElheny: Paintings, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York 2014 Dusty Groove, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago 2013 Josiah McElheny: Towards a Light Club, Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio State University, Columbus Josiah McElheny: Two Clubs at The Arts Club of Chicago, In collaboration with John Vinci, The Arts Club of Chicago, Chicago 2012 Josiah McElheny: Some Pictures of the Infinite, The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston Interactions of the Abstract Body, White Cube, London Some thoughts about the abstract body, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York 2011 The Past Was A Mirage I'd Left Far Behind, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, United Kingdom Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge, Other: Josiah McElheny’s Island Universe, Harvard Arts Museum, Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge 2010 Crystalline Modernity, -

Glenn Ligon Born in Bronx, New York, 1960 Lives

Glenn Ligon Born in Bronx, New York, 1960 Lives and works in New York NY Whitney Museum Independent Study Program, New York NY, 1985 BA, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT, 1982 Rhode Island School of Design, Providence RI, 1980 Solo Exhibitions 2016 Glenn Ligon, A Small Band, Rebuild Foundation, Stony Island Arts Bank, Chicago IL Glenn Ligon: Untitled (Bruise/Blues), Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa What We Said the Last Time, Luhring Augustine, New York NY We Need to Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn NY 2015 Glenn Ligon: Live, Regen Projects, Los Angeles CA Glenn Ligon: Well, it’s bye – bye / If you call that gone, Regen Projects, Los Angeles CA 2014 Glenn Ligon: Call and Response, Camden Arts Centre, London, England Glenn Ligon: Come Out, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England Glenn Ligon: Narratives, Schmucker Art Gallery, Gettysburg PA 2013 Glenn Ligon, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2012 Glenn Ligon: Neon, Luhring Augustine, New York NY 2011 Glenn Ligon: AMERICA, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NY; travelled to: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles CA; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth TX 2010 Neither Here nor There, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa 2009 Glenn Ligon: Off Book, Regen Projects and Regen Projects II, Los Angeles CA ‘Nobody’ and Other Songs, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England 2008 Figure / Paysage / Marine, Yvon Lambert, Paris, France Love and Theft, Power House Memphis, Memphis TX 2007 Glenn Ligon: No Room (Gold), Regen Projects, Los Angeles -

CAC Summer 2019 Magazine1.Pdf

SUMMER 2019 Dear Friends, This spring we’ve been fortunate at the Cantor to welcome several artists with whom we’ve developed meaningful and productive relationships that have provided enlightening experiences for all our visitors, as well as research and teach- ing opportunities for faculty, students, and other university Photograph by Stacy H. Geiken partners. Having the artists on-site enables us to explore with them what it means to be a 21st-century museum. Building all these relationships is critical to our future For instance, undergraduate and graduate students as an inclusive institution that engages with art, artists, and who took a winter-quarter course on the history of collect- art history to foster conversations about the world in which ing worked alongside artist Mark Dion as he chose objects we live. Your membership, attendance at our exhibitions, and made plans for the reinstallation of the Cantor’s and participation in our programs sustain us and allow us to Stanford Family Collections. Students and faculty also have continue our exploration of what it means to be a museum been in conversation in the exhibition galleries with artist in 2019. In order to ensure the Cantor’s existence well into Josiah McElheny and his Ohio State University collaborator, the future, we not only have to engage the next generation astronomy professor David Weinberg, about the making of in the world of art but we have to create in that generation Island Universe. Additionally, the two gave a compelling lec- the same passion for art that exists in so many of you. -

As a Hammer!), I Found Screenings, and Public Events, Providing Audiences an Myself Marveling Again and Again at the Seemingly Open and Lively Creative Forum

wexner center for the arts THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY In the Picture2012–2013 IN REVIEW Director’s Message Contents The Year in Pictures Exceptional Artistry Research and Education Outreach and Engagement Wexner Center Programs 2012–13 Thanks to You—Our Donors Wexner Center Staff and Volunteers A snapshot of life at the Wex: patrons and artists alike linked hundreds of photos (and memories) to our Instagram account. Director’s Equally powerful was the electrifying current between lifelong entertainer and social activist Harry Message Belafonte and the much younger Ohio State Law Professor and nationally acclaimed author Michelle Alexander. They too were brought together for the first time by the Wexner Center to offer further context around our screening of the documentary Sing Your Song, a chronicle of Belafonte’s brave and uncompromising pursuit of racial justice and equality that began in the 1950s. Their remarkable conversation highlighted On December 30, 2012, capacity crowds filled the Mr. Belafonte’s surpassing moral authority and galleries of the Wexner Center—and at several points indomitable spirit, alongside Ms. Alexander’s brilliant and during that clear but chilly day, hundreds were lined commanding intellect. Moreover, it revealed, to virtually up outside—for what would be their last chance to everyone’s surprise, the uncanny intersection in their see a landmark exhibition of Annie Leibovitz’s work. mutual (and fierce) commitment to expose and remedy Witnessing that moment was enormously gratifying the disproportionate incarceration of young African to all of us at the Wex—just one of many memorable American men in this country today.