Impact of Reconstituted Cytosol on Protein Stability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Cell Cytosol Stability to Segregation and Freezing-Out: Thermodynamic Aspect

1 Living Cell Cytosol Stability to Segregation and Freezing-Out: Thermodynamic aspect Viktor I. Laptev Russian New University, Moscow, Russian Federation The cytosol state in living cell is treated as homogeneous phase equilibrium with a special feature: the pressure of one phase is positive and the pressure of the other is negative. From this point of view the cytosol is neither solution nor gel (or sol as a whole) regardless its components (water and dissolved substances). This is its unique capability for selecting, sorting and transporting reagents to the proper place of the living cell without a so-called “pipeline”. To base this statement the theoretical investigation of the conditions of equilibrium and stability of the medium with alternative-sign pressure is carried out under using the thermodynamic laws and the Gibbs” equilibrium criterium. Keywords: living cellular processes; cytosol; intracellular fluid; cytoplasmic matrix; hyaloplasm matrix; segregation; freezing-out; zero isobare; negative pressure; homogeneous phase equilibrium. I. INTRODUCTION A. Inertial Motion in U,S,V-Space A full description of the thermodynamic state of a medium Cytosol in a living cell (intracellular fluid or cytoplasmic without chemical interactions is given by a relationship matrix, hyaloplasm matrix, aqueous cytoplasm) is a between the internal energy U, entropy S and volume V [5]. combination of the water dissolved substances. It places in the The mathematical procedure for a negative pressure supposes cell between the plasma membrane, the nucleus and a vacuole; using absolute values of the internal energy U and entropy S. it is a medium keeping granular-like and whisker-like The surface φ(U,S,V) = 0 corresponds to the all structures. -

Introduction to the Cell Cell History Cell Structures and Functions

Introduction to the cell cell history cell structures and functions CK-12 Foundation December 16, 2009 CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based collaborative model termed the “FlexBook,” CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and distribution of high quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide an adaptive environment for learning. Copyright ©2009 CK-12 Foundation This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Contents 1 Cell structure and function dec 16 5 1.1 Lesson 3.1: Introduction to Cells .................................. 5 3 www.ck12.org www.ck12.org 4 Chapter 1 Cell structure and function dec 16 1.1 Lesson 3.1: Introduction to Cells Lesson Objectives • Identify the scientists that first observed cells. • Outline the importance of microscopes in the discovery of cells. • Summarize what the cell theory proposes. • Identify the limitations on cell size. • Identify the four parts common to all cells. • Compare prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Introduction Knowing the make up of cells and how cells work is necessary to all of the biological sciences. Learning about the similarities and differences between cell types is particularly important to the fields of cell biology and molecular biology. -

VDAC: the Channel at the Interface Between Mitochondria and the Cytosol

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 256/257: 107–115, 2004. © 2004 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. 107 VDAC: The channel at the interface between mitochondria and the cytosol Marco Colombini Department of Biology, University of Maryland, MD, USA Abstract The mitochondrial outer membrane is not just a barrier but a site of regulation of mitochondrial function. The VDAC family of proteins are the major pathways for metabolite flux through the outer membrane. These can be regulated in a variety of ways and the integration of these regulatory inputs allows mitochondrial metabolism to be adjusted to changing cellular conditions. This includes total blockage of the flux of anionic metabolites leading to permeabilization of the outer membrane to small proteins followed by apoptotic cell death. (Mol Cell Biochem 256/257: 107–115, 2004) Key words: mitochondrion, outer membrane, apoptosis, isoforms, metabolism Introduction author’s view, see also ref. [6] for an alternative view). In- formation on VDAC can also be found on the VDAC web Mitochondria live, function, and reproduce in a very rich and page: www.life.umd.edu/vdac. friendly environment, the cytosol of the eukaryotic cell. Just as the plasma membrane is the interface between the inter- stitial space and the cytosol, so the mitochondrial outer The VDAC channels: Conservation and membrane is the interface between the cytosol and the mi- tochondrial spaces. Both separate the cell or the organelle specialization from its environment and both act as selective barriers to the entry and exit of matter. These membranes are also logical VDAC channels (Fig. 1) from a wide variety of sources (plants sites for control. -

A Physicochemical Perspective of Aging from Single-Cell Analysis Of

TOOLS AND RESOURCES A physicochemical perspective of aging from single-cell analysis of pH, macromolecular and organellar crowding in yeast Sara N Mouton1, David J Thaller2, Matthew M Crane3, Irina L Rempel1, Owen T Terpstra1, Anton Steen1, Matt Kaeberlein3, C Patrick Lusk2, Arnold J Boersma4*, Liesbeth M Veenhoff1* 1European Research Institute for the Biology of Ageing, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands; 2Department of Cell Biology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, United States; 3Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, United States; 4DWI-Leibniz Institute for Interactive Materials, Aachen, Germany Abstract Cellular aging is a multifactorial process that is characterized by a decline in homeostatic capacity, best described at the molecular level. Physicochemical properties such as pH and macromolecular crowding are essential to all molecular processes in cells and require maintenance. Whether a drift in physicochemical properties contributes to the overall decline of homeostasis in aging is not known. Here, we show that the cytosol of yeast cells acidifies modestly in early aging and sharply after senescence. Using a macromolecular crowding sensor optimized for long-term FRET measurements, we show that crowding is rather stable and that the stability of crowding is a stronger predictor for lifespan than the absolute crowding levels. Additionally, in aged cells, we observe drastic changes in organellar volume, leading to crowding on the *For correspondence: micrometer scale, which we term organellar crowding. Our measurements provide an initial [email protected] framework of physicochemical parameters of replicatively aged yeast cells. (AJB); [email protected] (LMV) Competing interest: See Introduction page 19 Cellular aging is a process of progressive decline in homeostatic capacity (Gems and Partridge, Funding: See page 19 2013; Kirkwood, 2005). -

Nucleolus: a Central Hub for Nuclear Functions Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, Sergey Razin, Yegor Vassetzky

Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, Sergey Razin, Yegor Vassetzky To cite this version: Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, et al.. Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions. Trends in Cell Biology, Elsevier, 2019, 29 (8), pp.647-659. 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.04.003. hal-02322927 HAL Id: hal-02322927 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02322927 Submitted on 18 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, Sergey Razin, Yegor Vassetzky To cite this version: Olga Iarovaia, Elizaveta Minina, Eugene Sheval, Daria Onichtchouk, Svetlana Dokudovskaya, et al.. Nucleolus: A Central Hub for Nuclear Functions. Trends in Cell Biology, Elsevier, 2019, 29 (8), pp.647-659. 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.04.003. hal-02322927 HAL Id: hal-02322927 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02322927 Submitted on 18 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. -

Nanocarriers for Protein Delivery to the Cytosol: Assessing the Endosomal Escape of Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide)-Poly(Ethylene Imine) Nanoparticles

nanomaterials Article Nanocarriers for Protein Delivery to the Cytosol: Assessing the Endosomal Escape of Poly(Lactide-co-Glycolide)-Poly(Ethylene Imine) Nanoparticles Marianna Galliani 1,2,* , Chiara Tremolanti 3,4 and Giovanni Signore 1,2,5,* 1 Center of Nanotechnology Innovation @NEST, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, 56127 Pisa, Italy 2 NEST, Scuola Normale Superiore, 56127 Pisa, Italy 3 Department of Pharmacy, University of Pisa, 56126 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] 4 Istituto di Fisiologia Clinica, National Research Council, 56124 Pisa, Italy 5 Fondazione Pisana per la Scienza ONLUS, 56121 Pisa, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (G.S.) Received: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 21 April 2019; Published: 23 April 2019 Abstract: Therapeutic proteins and enzymes are a group of interesting candidates for the treatment of numerous diseases, but they often require a carrier to avoid degradation and rapid clearance in vivo. To this end, organic nanoparticles (NPs) represent an excellent choice due to their biocompatibility, and cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs)-loaded poly (lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) NPs have recently attracted attention as versatile tools for targeted enzyme delivery. However, PLGA NPs are taken up by cells via endocytosis and are typically trafficked into lysosomes, while many therapeutic proteins and enzymes should reach the cellular cytosol to perform their activity. Here, we designed a CLEAs-based system implemented with a cationic endosomal escape agent (poly(ethylene imine), PEI) to extend the use of CLEA NPs also to cytosolic enzymes. We demonstrated that our system can deliver protein payloads at cytoplasm level by two different mechanisms: Endosomal escape and direct translocation. -

Roles of Cytosol and Cytoplasmic Particles in Nuclear Envelope Assembly and Sperm Pronuclear Formation in Cell-Free Preparations from Amphibian Eggs

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Roles of Cytosol and Cytoplasmic Particles in Nuclear Envelope Assembly and Sperm Pronuclear Formation in Cell-free Preparations from Amphibian Eggs MANFRED J . LOHKA and YOSHIO MASUI Department of Zoology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 1A1 . Dr. Lohka's present address is Department of Pharmacology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, Colorado 80262 . ABSTRACT A cell-free cytoplasmic preparation from activated Rana pipiens eggs could induce in demembranated Xenopus laevis sperm nuclei morphological changes similar to those seen during pronuclear formation in intact eggs . The condensed sperm chromatin underwent an initial rapid, but limited, dispersion . A nuclear envelope formed around the dispersed chro- matin and the nuclei enlarged . The subcellular distribution of the components required for these changes was examined by separating the preparations into soluble (cytosol) and partic- ulate fractions by centrifugation at 150,000 g for 2 h . Sperm chromatin was incubated with the cytosol or with the particulate material after it had been resuspended in either the cytosol, heat-treated (60 or 100°C) cytosol or buffer . We found that the limited dispersion of chromatin occurred in each of these ooplasmic fractions, but not in the buffer alone . Nuclear envelope assembly required the presence of both untreated cytosol and particulate material . Ultrastruc- tural examination of the sperm chromatin during incubation in the preparations showed that membrane vesicles of -200 nm in diameter, found in the particulate fraction, flattened and fused together to contribute the membranous components of the nuclear envelope . -

Membrane Structure and Function

Chapter 7 Membrane Structure and Function Lecture Outline Overview: Life at the Edge • The plasma membrane separates the living cell from its surroundings. • This thin barrier, 8 nm thick, controls traffic into and out of the cell. • Like all biological membranes, the plasma membrane is selectively permeable, allowing some substances to cross more easily than others. • The formation of a membrane that encloses a solution different from the surrounding solution while still permitting the uptake of nutrients and the elimination of waste products was a key event in the evolution of life. • The ability of the cell to discriminate in its chemical exchanges with its environment is fundamental to life. • It is the plasma membrane and its component molecules that make this selectivity possible. Concept 7.1 Cellular membranes are fluid mosaics of lipids and proteins. • The main macromolecules in membranes are lipids and proteins, but carbohydrates are also important. • The most abundant lipids are phospholipids. • Phospholipids and most other membrane constituents are amphipathic molecules, which have both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions. Membrane models have evolved to fit new data. • The arrangement of phospholipids and proteins in biological membranes is described by the fluid mosaic model. • In this model, the membrane is a fluid structure with a “mosaic” of various proteins embedded in or attached to a double layer (bilayer) of phospholipids. • Models of membranes were developed long before membranes were first seen with electron microscopes in the 1950s. • In 1915, membranes isolated from red blood cells were chemically analyzed and found to be composed of lipids and proteins. • In 1925, E. -

1 Introduction to Cell Biology

1 Introduction to cell biology 1.1 Motivation Why is the understanding of cell mechancis important? cells need to move and interact with their environment ◦ cells have components that are highly dependent on mechanics, e.g., structural proteins ◦ cells need to reproduce / divide ◦ to improve the control/function of cells ◦ to improve cell growth/cell production ◦ medical appli- cations ◦ mechanical signals regulate cell metabolism ◦ treatment of certain diseases needs understanding of cell mechanics ◦ cells live in a mechanical environment ◦ it determines the mechanics of organisms that consist of cells ◦ directly applicable to single cell analysis research ◦ to understand how mechanical loading affects cells, e.g. stem cell differentation, cell morphology ◦ to understand how mechanically gated ion channels work ◦ an understanding of the loading in cells could aid in developing struc- tures to grow cells or organization of cells more efficiently ◦ can help us to understand macrostructured behavior better ◦ can help us to build machines/sensors similar to cells ◦ can help us understand the biology of the cell ◦ cell growth is affected by stress and mechanical properties of the substrate the cells are in ◦ understanding mechan- ics is important for knowing how cells move and for figuring out how to change cell motion ◦ when building/engineering tissues, the tissue must have the necessary me- chanical properties ◦ understand how cells is affected by and affects its environment ◦ understand how mechanical factors alter cell behavior (gene expression) -

Cell Structure and Function Answered Review SP 08.Pdf

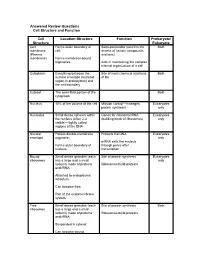

Answered Review Questions Cell Structure and Function Cell Location-Structure Function Prokaryote/ Structure Eukaryote Cell Forms outer boundary of Semi-permeable (restricts the Both membrane cell; access of certain compounds (Plasma and ions) membrane) Forms membrane-bound organelles Aids in maintaining the complex internal organization of a cell Cytoplasm Everything between the Site of most chemical reactions Both nuclear envelope (nucleoid of life region in prokaryotes) and the cell boundary Cytosol The semi-fluid portion of the Both cytoplasm Nucleus 10% of the volume of the cell Mission control—manages Eukaryotes protein synthesis only Nucleolus Small dense spheres within Genes for ribosomal RNA Eukaryotes the nucleus (often 2-3 (building block of ribosomes) only visible)—tightly coiled regions of the DNA Nuclear Porous double-membrane Protects the DNA Eukaryotes envelope organelle; only mRNA exits the nucleus Forms outer boundary of through pores after nucleus transcription Bound Small dense granules (each Site of protein synthesis Eukaryotes ribosomes has a large and a small only subunit) made of proteins Ribosomes build proteins and rRNA; Attached to endoplasmic reticulum; Can become free; Part of the endomembrane system Free Small dense granules (each Site of protein synthesis Both ribosomes has a large and a small subunit) made of proteins Ribosomes build proteins and rRNA; Suspended in cytosol; Can become bound Rough Network of membranous Modify proteins Eukaryotes endoplasmic tubes dotted with bound only reticulum ribosomes; Many proteins are modified here by cleaving the Loosely surrounds the polypeptide, forming quaternary nucleus; structures, removing amino acids or adding non-protein Part of the endomembrane substances (e.g. -

Is There an Alternative Pathway for Starch Synthesis?'

Plant Physiol. (1992) 100, 560-564 Received for publication February 18, 1992 0032-0889/92/1 00/0560/05/$01 .00/0 Accepted May 15, 1992 Is There an Alternative Pathway for Starch Synthesis?' Thomas W. Okita Institute of Biological Chemistry, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington ABSTRACT 15, 17), indicating that the basic enzymology of starch syn- In leaf tissue, carbon enters starch via the gluconeogenesis thesis is the same in amyloplasts as in chloroplasts. The flow pathway where D-glycerate 3-phosphate formed from CO2 fixation of carbon and the exchange of metabolites between the is converted into hexose monophosphates within the chloroplast amyloplast and cytosol in developing sink organs, however, stroma. In starch-containing sink organs, evidence has been ob- are not identical to the processes established for leaves (1, 6, tained indicating that the flow of carbon into starch follows a 7, 9, 17, 19). different pathway whereby hexose monophosphates formed from An alternative pathway of starch synthesis recently has sucrose are transported into the amyloplast, a plastid specialized been proposed based on the capacity of both chloroplasts in starch accumulation. In both chloroplasts and amyloplasts, the and amyloplasts to transport ADPGlc (16 and refs. cited formation of ADPglucose, the substrate for starch synthase, is therein). In this review, I first summarize the latest develop- controlled by the activity of ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase, a key ments regulatory enzyme of starch synthesis localized in the plastid. in starch biosynthesis and then discuss whether the Recently, an alternative pathway of starch synthesis has been operation of this proposed alternative pathway of starch proposed in which ADPglucose is synthesized from sucrose and synthesis is compatible with our present knowledge of the transported directly into the plastid compartment, where it is used biochemistry and genetics of starch biosynthesis. -

Manipulation of Cellular Processes Via Nucleolus Hijaking in the Course of Viral Infection in Mammals

cells Review Manipulation of Cellular Processes via Nucleolus Hijaking in the Course of Viral Infection in Mammals Olga V. Iarovaia *, Elena S. Ioudinkova, Artem K. Velichko and Sergey V. Razin Institute of Gene Biology Russian Academy of Sciences, 119334 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (E.S.I.); [email protected] (A.K.V.); [email protected] (S.V.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-499-135-97-87 Abstract: Due to their exceptional simplicity of organization, viruses rely on the resources, molecular mechanisms, macromolecular complexes, regulatory pathways, and functional compartments of the host cell for an effective infection process. The nucleolus plays an important role in the process of interaction between the virus and the infected cell. The interactions of viral proteins and nucleic acids with the nucleolus during the infection process are universal phenomena and have been described for almost all taxonomic groups. During infection, proteins of the nucleolus in association with viral components can be directly used for the processes of replication and transcription of viral nucleic acids and the assembly and transport of viral particles. In the course of a viral infection, the usurpation of the nucleolus functions occurs and the usurpation is accompanied by profound changes in ribosome biogenesis. Recent studies have demonstrated that the nucleolus is a multifunctional and dynamic compartment. In addition to the biogenesis of ribosomes, it is involved in regulating the cell cycle and apoptosis, responding to cellular stress, repairing DNA, and transcribing RNA polymerase II-dependent genes. A viral infection can be accompanied by targeted transport of viral Citation: Iarovaia, O.V.; Ioudinkova, proteins to the nucleolus, massive release of resident proteins of the nucleolus into the nucleoplasm E.S.; Velichko, A.K.; Razin, S.V.