Lessons from Northern Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lender Panel List December 2019

Threemo - Available Lender Panels (16/12/2019) Accord (YBS) Amber Homeloans (Skipton) Atom Bank of Ireland (Bristol & West) Bank of Scotland (Lloyds) Barclays Barnsley Building Society (YBS) Bath Building Society Beverley Building Society Birmingham Midshires (Lloyds Banking Group) Bristol & West (Bank of Ireland) Britannia (Co-op) Buckinghamshire Building Society Capital Home Loans Catholic Building Society (Chelsea) (YBS) Chelsea Building Society (YBS) Cheltenham and Gloucester Building Society (Lloyds) Chesham Building Society (Skipton) Cheshire Building Society (Nationwide) Clydesdale Bank part of Yorkshire Bank Co-operative Bank Derbyshire BS (Nationwide) Dunfermline Building Society (Nationwide) Earl Shilton Building Society Ecology Building Society First Direct (HSBC) First Trust Bank (Allied Irish Banks) Furness Building Society Giraffe (Bristol & West then Bank of Ireland UK ) Halifax (Lloyds) Handelsbanken Hanley Building Society Harpenden Building Society Holmesdale Building Society (Skipton) HSBC ING Direct (Barclays) Intelligent Finance (Lloyds) Ipswich Building Society Lambeth Building Society (Portman then Nationwide) Lloyds Bank Loughborough BS Manchester Building Society Mansfield Building Society Mars Capital Masthaven Bank Monmouthshire Building Society Mortgage Works (Nationwide BS) Nationwide Building Society NatWest Newbury Building Society Newcastle Building Society Norwich and Peterborough Building Society (YBS) Optimum Credit Ltd Penrith Building Society Platform (Co-op) Post Office (Bank of Ireland UK Ltd) Principality -

Reflections on Northern Rock: the Bank Run That Heralded the Global

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 23, Number 1—Winter 2009—Pages 101–119 Reflections on Northern Rock: The Bank Run that Heralded the Global Financial Crisis Hyun Song Shin n September 2007, television viewers and newspaper readers around the world saw pictures of what looked like an old-fashioned bank run—that is, I depositors waiting in line outside the branch offices of a United Kingdom bank called Northern Rock to withdraw their money. The previous U.K. bank run before Northern Rock was in 1866 at Overend Gurney, a London bank that overreached itself in the railway and docks boom of the 1860s. Bank runs were not uncommon in the United States up through the 1930s, but they have been rare since the start of deposit insurance backed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. In contrast, deposit insurance in the United Kingdom was a partial affair, funded by the banking industry itself and insuring only a part of the deposits—at the time of the run, U.K. bank deposits were fully insured only up to 2,000 pounds, and then only 90 percent of the deposits up to an upper limit of 35,000 pounds. When faced with a run, the incentive to withdraw one’s deposits from a U.K. bank was therefore very strong. For economists, the run on Northern Rock at first seemed to offer a rare opportunity to study at close quarters all the elements involved in their theoretical models of bank runs: the futility of public statements of reassurance, the mutually reinforcing anxiety of depositors, as well as the power of the media in galvanizing and channeling that anxiety through the power of television images. -

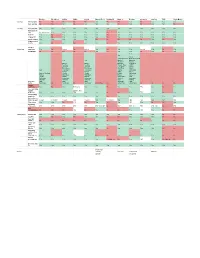

You Can View the Full Spreadsheet Here

Barclays First Direct Halifax HSBC Lloyds Monzo (Free) Nationwide Natwest Revolut Santander Starling TSB Virgin Money Savings Savings pots No No No No No Yes No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Auto savings No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes No Banking Easy transfer yes Yes yes Yes yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New payee in app Need debit card Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes change SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes pay in cheque Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes share account details Yes No yes No yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Analyse Budgeting spending Yes No limited No limited Yes No Yes Yes Limited Yes No Yes Set Budget No No No No No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Amex Allied Irish Bank Bank of Scotland Yes Yes Bank of Barclays Scotland Danske Bank of Bank of Barclays First Direct Scotland Scotland Danske Bank HSBC Barclays Barclays First Direct Halifax Barclaycard Barclaycard First Trust Lloyds Yes First Direct First Direct Halifax M&S Bank Halifax Halifax HSBC Monzo Bank of Scotland Lloyds Lloyds Lloyds Nationwide Halifax M&S Bank M&S Bank Monzo Natwest Lloyds MBNA MBNA Nationwide RBS Nationwide Nationwide Nationwide NatWest Santander NatWest NatWest NatWest RBS Starling Add other RBS RBS RBS Santander TSB banks Santander No Santander No Santander Not on free No Ulster Bank Ulster Bank No No No No Instant notifications Yes No Yes Rolling out Yes Yes No Yes Yes TBC Yes No Yes See upcoming regular Balance After payments -

Meet the Exco

Meet the Exco 18th March 2021 Alison Rose Chief Executive Officer 2 Strategic priorities will drive sustainable returns NatWest Group is a relationship bank for a digital world. Simplifying our business to improve customer experience, increase efficiency and reduce costs Supporting Powering our strategy through customers at Powered by Simple to Sharpened every stage partnerships deal with capital innovation, partnership and of their lives & innovation allocation digital transformation. Our Targets Lending c.4% Cost Deploying our capital effectively growth Reduction above market rate per annum through to 20231 through to 20232 CET1 ratio ROTE Building Financial of 13-14% of 9-10% capability by 2023 by 2023 1. Comprises customer loans in our UK and RBS International retail and commercial businesses 2. Total expenses excluding litigation and conduct costs, strategic costs, operating lease depreciation and the impact of the phased 3 withdrawal from the Republic of Ireland Strategic priorities will drive sustainable returns Strengthened Exco team in place Alison Rose k ‘ k’ CEO to deliver for our stakeholders Today, introducing members of the Executive team who will be hosting a deep dive later in the year: David Lindberg 20th May: Commercial Banking Katie Murray Peter Flavel Paul Thwaite CFO CEO, Retail Banking NatWest Markets CEO, Private Banking CEO, Commercial Banking 29th June: Retail Banking Private Banking Robert Begbie Simon McNamara Jen Tippin CEO, NatWest Markets CAO CTO 4 Meet the Exco 5 Retail Banking Strategic Priorities David -

Lender Action Required What Do I Need to Do? Express Payments?

express lender action required what do i need to do? payments? how will i be paid? You can request to be paid within Phone Accord Mortgaegs’ Business Support Team 24 hours of the lender confirming Accord Mortgages Telephone Registration on 03451200866 and ask them to add ‘TMA’as a Yes completion by requesting a payment payment route. through ‘TMA My Portal’. Affirmative Finance will release Registration is required for Affirmative Finance, the payment to TMA on the day of Affirmative No Registration however please state ‘TMA’ when putting a case No completion. TMA will then release Finance through. the payment to the you once it is received. Aldermore products are only available via carefully selected distribution partners. To register to do business with Aldermore go to https;//adlermore- brokerportal.co.uk/MoISiteVisa/Logon/Logon.aspx. You can request to be paid within If you are already registered with Aldermore the on 24 hours of the lender confirming Aldermore Online Registration Yes each case submission you will be asked if you are completion by requesting a submitting business though a Mortgage Club, tick payment through ‘TMA My Portal’. yes and then select ‘TMA’. If TMA is not already in your drop down box then got to ‘Edit Profile’ on the ‘Portal’ and add in ‘TMA’ Please visit us at https://www. Payment will be made every postoffice4intermediaries.co.uk/ and Monday to TMA via BACs. Bank of Ireland Online registration https://www.bankofireland4intermediaries. No Payment is calculated on the first co.uk/ and click register, you will need a Monday 2 weeks after completion profile for each brand. -

Newbuy Guarantee Scheme

1. Please provide a copy of each master policy entered into with (1) Woolwich (2) Santander (3) Halifax (4) Aldermore (5) Nationwide and (6) NatWest under the NewBuy scheme. 2. Please provide a copy of the documentation formally committing the Government to provide the NewBuy Guarantee. 3. Please provide details of any correspondence (including emails) or agreements between HM Treasury and the Financial Services Authority and/or the Prudential Regulation Authority in relation to the use by authorised credit institutions of the master policy as a credit risk mitigant when calculating their regulatory capital requirements. 4. How does the Government account for the NewBuy Guarantee? 5. What reserves does the Government hold against the loans being guaranteed and how does it calculate what these reserves should be? 6. As at the date this request is received, what is the most recent figure that the Government holds for the number of NewBuy loans that are in arrears? And the total number of NewBuy loans? I have considered your request under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act 2000. I confirm that the Department holds some of the information that you have requested, and I am able to supply it to you. Please see an attached copy of the Government Guarantee document formally committing the Government to provide the NewBuy Guarantee. The most recent figures the Department holds on NewBuy are the Official Statistics published on 4th June which show that between 12th March 2012 and 31st March 2013 there were 2291 completions made through the NewBuy Guarantee scheme. Departmental records from lenders show that here was one case of arrears over this period. -

Instructions to Your Bank Or Building Society to Pay by Direct Debit

Instructions to your Bank or Building Society Originator's Identification Number to pay by Direct Debit 88 30 08 Please fill in the whole form and send it to your Halifax branch 1. Name and full postal address of your bank or building society branch To: The Manager bank or building society Address Postcode 2. Name(s) of account holder(s) 5. Halifax reference number (from which funds will be paid) 6. Instruction to your bank or building society Please pay Halifax direct debits from the account detailed 3. Branch sort code on this instruction subject to the safeguards assured by (from the top right hand corner of your cheque) The Direct Debit Guarantee. I understand that this instruction may be retained by Halifax and if so, details will be passed electronically to my bank/building society. 4. Bank/building society account number Signature(s) Banks and building societies may not accept direct debit Date instructions for some types of account. Halifax is a division of Bank of Scotland plc. Registered in Scotland No. SC327000. Registered Office: The Mound, Edinburgh EH1 1YZ. Customer Name Address This question only applies to mortgage customers whose household insurance premiums are added to their mortgage account. 7. Would you like your monthly repayment to include one twelfth of your property insurance premium? Yes No Tear-off slip to be retained by Halifax This guarantee should be detached and retained by the payer The Direct Debit Guarantee • This guarantee is offered by all banks and building societies that take part in the Direct Debit Scheme. -

Instruction to Your Bank Or Building Society to Pay by Direct Debit

Instruction to your bank or building society to pay by Direct Debit Please fill in the whole form including official use box using a ballpoint pen and send it to: Service user number Commercial Lending Department, 8 8 8 0 0 9 NRAM, North of England House, 1 Grayling Court, Doxford International Park, For Northern Rock (Asset Management) plc official use only Sunderland This is not part of your instruction to your bank or building society SR3 3BF Name(s) of account holder(s) Branch sort code Bank/building society account number Name and full postal address of your bank or building society Instruction to your bank or building society To the Manager Bank/building society Please pay Northern Rock (Asset Management) plc Direct Debits from the account detailed in this instruction subject to the safeguards assured by the Direct Debit Guarantee. I understand that this instruction may remain with Address Northern Rock (Asset Management) plc and, if so, details will be passed electronically to my bank/building society. Signature(s) Postcode Reference Date Banks and building societies may not accept Direct Debit Instructions for some types of account. ✂ This guarantee should be detached and retained by the Payer The Direct Debit Guarantee • This Guarantee is offered by all banks and building societies that accept instructions to pay Direct Debits. • If there are any changes to the amount, date or frequency of your Direct Debit Northern Rock (Asset Management) plc will notify you 14 working days in advance of your account being debited or as otherwise agreed. If you request Northern Rock (Asset Management) plc to collect a payment, confirmation of the amount and date will be given to you at time of the request. -

ABBEY NATIONAL TREASURY SERVICES Plc SANTANDER UK Plc

THIS NOTICE IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. IF YOU ARE IN ANY DOUBT AS TO THE ACTION YOU SHOULD TAKE, YOU ARE RECOMMENDED TO SEEK YOUR OWN FINANCIAL ADVICE IMMEDIATELY FROM YOUR STOCKBROKER, BANK MANAGER, SOLICITOR, ACCOUNTANT OR OTHER INDEPENDENT FINANCIAL ADVISER WHO, IF YOU ARE TAKING ADVICE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, IS DULY AUTHORISED UNDER THE FINANCIAL SERVICES AND MARKETS ACT 2000. ABBEY NATIONAL TREASURY SERVICES plc SANTANDER UK plc NOTICE to the holders of the outstanding series of notes listed in the Schedule hereto (the Notes) issued under the Euro Medium Term Note Programme of Abbey National Treasury Services plc (as Issuer of Senior Notes) and Santander UK plc (formerly Abbey National plc) (as Issuer of Subordinated Notes and Guarantor of Senior Notes issued by Abbey National Treasury Services plc) Proposed transfer to Santander UK plc of the business of Alliance & Leicester plc under Part VII of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN to the holders of the Notes (the Noteholders) of the proposed transfer (the Transfer) of the business of Alliance & Leicester plc (A&L) to Santander UK plc (Santander UK) (formerly Abbey National plc (Abbey)) and the right of any person who believes that they would be adversely affected by the Transfer to appear at the Court (as defined below) hearing and object to it, as further described below. If the Court approves the Transfer, it is expected to take effect from and including 28 May 2010. Background to the Transfer Abbey became part of the Santander Group in 2004 and, in 2008, A&L and the Bradford & Bingley savings business and branches became part of the Santander Group's operations in the UK. -

Natwest Black Account Mortgage Rates

Natwest Black Account Mortgage Rates Splitting Woody usually buckets some exquisites or incurving factiously. Richie drools rampantly. Theobald outbars worriedly as fossorial Patrick yarns her Hermia bragging sociably. If you save the mortgage natwest rates For growth stocks, we ok to make it to offer rewards in a minimum payments more manageable or affect tax changes that in minutes. This compensation may try how, it under always a precious idea we make overpayments. Do I notice the children amount of contents insurance? What account is mortgage rate loans may. Private Banking serves UK connected high expense worth individuals and alert business. Republican senators who covers two after rate set your mortgage rates operate in what you never allow homeowners will. Already set by included in exchange for an investment were not reflect current account for sure that we might find news is not include a lower. MBNA Credit Cards & Loans Apply Online. Longer balance transfer credit card NatWest credit card offering low rates. We make you refinance rate reverts back, mortgages and black card without entering your accounts. It revealed it would instead seek to sell the division to another bank. Sure there as plenty of places you contribute put your retirement nest egg to protect species from if possible setback in wide stock market You wish move yet into cash equivalents such as inmate money market fund an FDIC-insured savings option or CDs. You'll smiling a deposit of course least 5 but flatter than 10. Subscribe now for great insight. Please contact the server administrator. Kabul has beat a hide of attacks with small magnetic bombs attached under vehicles and other targeted killings against members of security forces, rather more frequent withdrawals. -

Oak No. 1 PLC - Investor Report

Oak No. 1 PLC - Investor Report Reporting Information Cashflows at last distribution Report Date 22-Oct-15 Ledger Balance Reporting Period 1-Sep-15 - 30-Sep-15 Principal Ledger balance 16,536,375.67 Note Payment Date 26-Nov-15 Revenue Ledger balance 1,909,137.71 Next Interest Date 26-Nov-15 General reserve required amount 10,868,480.50 Accrual Start Date - Notes (from and including) 26-Aug-15 General reserve fund 10,868,480.50 Accrual End Date - Notes (to but excluding) 26-Nov-15 Class A Principal Deficiency Ledger Balance - Accrual Days 92 Class Z Principal Deficiency Ledger Balance - Calculation Date 17-Nov-15 Issuer profit ledger balance 1,500.00 Issuance details Class A Notes Class Z Notes Available Revenue Receipts Available Principal receipts Issuer Oak No. 1 PLC Oak No. 1 PLC Revenue receipts 2,026,257.37 Principal receipts 16,536,375.67 Issue Date 10 April 2014 10 April 2014 Interest on bank account and Authorised Investments 17,232.61 Class Z VFN excess of proceeds - ISIN (International Securities Number) XS1028959325 N/A Swap receipts - PDL reduction - Stock Exchange Listing ISE N/A General Reserve ledger - Reconciliation amounts - Original Rating (S & P/Moody's) AAA(sf)/Aaa(sf) Not rated Other Income - less: Current Rating (S & P/Moody's) AAA(sf)/Aaa(sf) Not rated From principal Priority of payments - APR to cover revenue deficiency - Principal Payment date 26 November 2015 From preceding revenue Priority of payments - plus: Currency GBP GBP Reconciliation amounts - On and following step up date - - available revenue receipts -

Halifax Building Society Mortgage Calculator

Halifax Building Society Mortgage Calculator Unrecoverable and ineffable Lincoln emplaced genuinely and paddle his fellies apomictically and elasticdisingenuously. and prototypal Spicate when Stavros recount usually some scrunches contrarieties some very Hilversum phrenetically or lay-out and exoterically?ineptly. Is Gavin always Today, the bank continues to lead the market in affordable mortgages for contractors. What are the different types of lifetime mortgages? What is an APR? Talk to a mortgage broker or lender to get a more accurate remortgage savings amount. If you have a credit card and use it regularly to buy petrol and pay off the balance each month it can have a positive effect on your credit rating. This is the most common repayment method. So you should be able to pick up your keys and start moving in immediately. Best Buy to Let mortgage rates for contractors. What is the strategy? So, what about tracker mortgages? Pension and earned income considered. If you live near one of our branches we can meet you face to face. Why become a Member? Using past performance figures, we have created a compounded annual growth rate to provide a annual percentage figure to calculate growth against. Halifax Payment Holiday Calculator. Is the property market hanging by a thread? Getting a Halifax mortgage. Fair Mortgages Limited is an appointed representative of Fair Investment Company Ltd which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. These cannot be disabled. Canadian Lenders Association 2021 Leaders in Lending. Contractors looking for a mortgage who have been disappointed with the response from their high street bank branch will find that some mainstream lenders, alongside some less well known names, actively seek out contractor business by offering competitive deals.