Sex, Stereotypes and Stripping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

Unusual Sexual Behavior

UNUSUAL SEXUAL BEHA VIOR UNUSUAL SEXUAL BEHAVIOR THE STANDARD DEVIATIONS By DAVID LESTER, Ph.D. R ichard Stockton State College Pomona, New Jersey CHARLES C THOMAS • PUBLISHER Springfield • Illinois • U.S.A. Published and Distributed Throughout the World by CHARLES C THOMAS. PUBLISHER Bannerstone House 301-327 East Lawrence Avenue, Springfield, I1!inois, U.S.A. This book is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher. ©1975, by CHARLES C THOMAS. PUBLISHER ISBN 0-398-03343-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 74 20784 With THOMAS BOOKS careful attention is given to all details of manufacturing and design. It is the Publisher's desire to present books that are satisfactory as to their physical qualities and artistic possibilities and appropriate for their particular use. THOMAS BOOKS will be true to those laws of quality that assure a good name and good will. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lester, David, 1942- Unusual sexual behavior. Includes index. 1. Sexual deviation. I. Title. [DNLM: 1. Sex deviation. WM610 L642ul RC577.IA5 616.8'583 74-20784 ISBN 0-398-03343-9 Printed in the United States of America A-2 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this book is to review the literature on sexual deviations. Primarily the review is concerned with the research literature and not with clinical studies. However, occasional refer ence is made to the conclusions of clinical studies and, in particular, to psychoanalytic hypotheses about sexual deviations. The coverage of clinical and psychoanalytic ideas is by no means intended to be exhaustive, unlike the coverage of the research literature. -

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

Toxic Strip Clubs"

Theology and Sexuality 16(1):19-58, 2010 "TOXIC STRIP CLUBS": THE INTERSECTION OF RELIGION, LAW, AND FANTASY Judith Lynne Hanna, Ph.D.1 Affiliate Senior Research Scientist Department of Anthropology University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-1610 USA [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper examines a segment of the politically active Christian Right (SPACR) that works toward controlling sexual expression in accord with their desire to live in a Scripture-based society. At the local and state levels, a focus is on adult entertainment exotic dance. Under the United States First Amendment to the Constitution and established law, exotic dance, a form of expression, cannot be banned solely on the grounds that some people deem it immoral. Recasting their religion-based objections within the Supreme Court “adverse secondary effects” doctrine (governments may regulate clubs if the aim is to prevent crime, property depreciation, and disease), SPACR pursues its opposition to exotic dance through laws and social actions that harm the business. The rationale for hostility is compared to facts. SPACR's secular reasoning gains support for regulations to marginalize and punish those who do not adhere to their moral values causing free speech advocates, consumers, and involved businesses to fight back. At issue are civil liberties under the U.S. Constitution, the separation of church and state, and harm to the economy. Keywords: Christian Right, exotic dance adult entertainment (strip clubs), separation of church and state, civil liberties, theocracy, democracy 1Judith Lynne Hanna (Ph.D., Columbia University) has published widely, including The Encyclopedia of Religion; Journal of the American Academy of Religion; Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society; and Journal of Sex Research. -

Bare Minimum: Stripping Pay for Independent Contractors in the Share Economy

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 23 (2016-2017) Issue 2 William & Mary Journal of Women and Article 5 the Law January 2017 Bare Minimum: Stripping Pay for Independent Contractors in the Share Economy Michael H. LeRoy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Repository Citation Michael H. LeRoy, Bare Minimum: Stripping Pay for Independent Contractors in the Share Economy, 23 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 249 (2017), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/ vol23/iss2/5 Copyright c 2017 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl BARE MINIMUM: STRIPPING PAY FOR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS IN THE SHARE ECONOMY MICHAEL H. LEROY* SUMMARY My study explores a small but revealing corner of the share economy, where an individual’s private resources are bartered for limited use by others in exchange for compensation. Strip clubs create value for owners by commoditizing sexual labor. Clubs avoid employment in favor of independent contracting with dancers. They pay no wages or benefits; patrons pay dancers with fees and tips. But clubs extract entry fees from dancers who work; require them to rent dressing rooms and stage time; and compel them to share tips with DJs, emcees, house moms, bouncers, and bartenders. My research identified seventy-five federal and state court rulings on wage claims by exotic dancers. In thirty-eight cases, courts ruled that dancers were employees; only three courts ruled that dancers were independent contractors. -

Reviewed Books

REVIEWED BOOKS - Inmate Property 6/27/2019 Disclaimer: Publications may be reviewed in accordance with DOC Administrative Code 309.04 Inmate Mail and DOC 309.05 Publications. The list may not include all books due to the volume of publications received. To quickly find a title press the "F" key along with the CTRL and type in a key phrase from the title, click FIND NEXT. TITLE AUTHOR APPROVEDENY REVIEWED EXPLANATION DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.2 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 a Is pornography. Depicts teenage sexuality, nudity, 12 Beast Vol.3 OKAYADO X 12/11/2018 exposed breasts. Workbook of Magic Donald Tyson X 1/11/2018 SR per Mike Saunders 100 Deadly Skills Survivor Edition Clint Emerson X 5/29/2018 DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey X 4/6/2017 WCI DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b. b Teaches fighting techniques along with general fitness DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Is inconsistent with or poses a threat to the safety, 100 Things You’re Not Supposed to Know Russ Kick X 11/10/2017 WCI treatment or rehabilitative goals of an inmate. 100 Ways to Win a Ten Spot Paul Zenon X 10/21/2016 WRC DOC 309.04 4 (c) 8 b, c. b. Poses a threat to the security 100 Years of Lynchings Ralph Ginzburg X reviewed by agency trainers, deemed historical Brad Graham and 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genuis Kathy McGowan X 12/23/10 WSPF 309.05(2)(B)2 309.04(4)c.8.d. -

Gentlemen's Club

CHRIS BUCK — BOOKS GENTLEMEN’S CLUB PARTNERS OF EXOTIC DANCERS (SPRING 2021) Known for his uneasy portraits of celebrities, Chris Buck was looking for a subject that continued his exploration of strength and vulnerability, and found it in the partners of exotic dancers. The result is Buck’s most surprising and compelling work: forty interviews and photo sittings across North America with people in committed relationships with strip club dancers. Author and former dancer Lily Burana has written the foreword to Gentlemen’s Club. DETAILS By turns raffish, gallant, sly and touchingly vulnerable, this is a wonderful band of gentlemen—even if some of them aren’t, strictly speaking, men—and this book is a Photographer/Author: Chris Buck reminder of basic humanity in a seemingly inhuman time. Foreword: Lily Burana — Mary Gaitskill, author of This is Pleasure Design: Alex Camlin Format: Hardcover 7.625 x 10.25 inches Chris Buck’s pictures give us strange attractors, weaknesses in human psychic energy fields, blocked 90 color photographs emotions, yearnings for radicality, the normalcy of sexual fantasies, need, the romance of desire, and 256 pages, 40 interviews efflorescent tattered love. Publisher: Norman Stuart Publishing — Jerry Saltz, Pulitzer Prize winning art critic, New York Magazine Release Date: Spring 2021 Chris Buck has taken a widely photographed subject and made it wholly his own. His interviews with dancers’ partners are incisive and powerful, but it is his accompanying photographs that reveal this world in all of its gorgeous complexity: darkness and levity, uncertainty and hope, bravado and vulnerability. — Karen Abbott, New York Times bestselling author of The Ghosts of Eden Park GENTLEMEN’S CLUB CHRIS BUCK FOREWORD by Lily Burana The private life of a stripper is one of the enduring mysteries in the public consciousness. -

Erotic Ambiguities : the Female Nude in Art / 30111 Helen Mcdonald

1111 2 3 4 5111 EROTIC AMBIGUITIES 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 3111 Art is always ambiguous. When it involves the female body it can also be erotic. 4 Erotic Ambiguities is a study of how contemporary women artists have recon- 5 ceptualised the figure of the female nude. Helen McDonald shows how, over 6 the past thirty years, artists have employed the idea of ambiguity to dismantle 7 the exclusive, classical ideal enshrined in the figure of the nude, and how they 8 have broadened the scope of the ideal to include differences of race, ethnicity, 9 sexuality and disability as well as gender. 20111 McDonald discusses the work of a wide range of women artists, including 1 Barbara Kruger, Judy Chicago, Mary Duffy, Zoe Leonard, Tracey Moffatt, Pat 2 Brassington and Sally Smart. She traces the shift in feminist art practices from 3 the early challenge to patriarchal representations of the female nude to contem- 4 porary, ‘postfeminist’ practices, influenced by theories of performativity, queer 5 theory and postcoloniality. McDonald argues that feminist efforts to develop 6 a more positive representation of the female body need to be reconsidered, 7 in the face of the resistant ambiguities and hybrid complexities of visual art in 8 the late 1990s. 9 30111 Helen McDonald is an Honorary Fellow in the School of Fine Arts, Classical 1 Studies and Archaeology at the University of Melbourne. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 40111 1 2 3 44111 i RUNNING HEAD 1111 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 20111 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 30111 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 40111 1 2 3 44111 ii RUNNING HEAD -

On Voyeurism: Being Seen on the Modern Stage

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2020 On Voyeurism: Being Seen on the Modern Stage Megan M. Mobley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons Recommended Citation Mobley, Megan M., "On Voyeurism: Being Seen on the Modern Stage" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2062. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/2062 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON VOYEURISM: BEING SEEN ON THE MODERN STAGE by MEGAN MOBLEY (Under the Direction of Dustin Anderson) ABSTRACT At the end of the nineteenth century, playwrights grew more interested in exploring the ramifications of the gaze, looking and being looked at. For existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, the gaze causes a never-ending battle between our subjective selves, how we view ourselves, and our objective selves, or how others view us. The knowledge of the Other’s gaze allows us to self- reflect on our own existence. Sartre and Oscar Wilde each incorporate the gaze into their plays to explore the battle between our subjective and objective selves, gendered perception, differences in perception, and to undercut or demonstrates the dominant structures of seeing. By first exploring Sartre’s No Exit, I can observe how Sartre’s three main characters demonstrate Mulvey’s theories of the male gaze, a structure of looking which is influenced by the dominant social order. -

Homelessness, Survival Sex and Human Trafficking: As Experienced by the Youth of Covenant House New York

Homelessness, Survival Sex and Human Trafficking: As Experienced by the Youth of Covenant House New York May 2013 Jayne Bigelsen, Director Anti-Human Trafficking Initiatives, Covenant House New York*: Stefanie Vuotto, Fordham University: Tool Development and Validation Project Coordinators: Kimberly Addison, Sara Trongone and Kate Tully Research Assistants/Legal Advisors: Tiffany Anderson, Jacquelyn Bradford, Olivia Brown, Carolyn Collantes, Sharon Dhillon, Leslie Feigenbaum, Laura Ferro, Andrea Laidman, Matthew Jamison, Laura Matthews-Jolly, Gregory Meves, Lucas Morgan, Lauren Radebaugh, Kari Rotkin, Samantha Schulman, Claire Sheehan, Jenn Strashnick, Caroline Valvardi. With a special thanks to Skadden Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP and Affiliates for their financial support and to the Covenant House New York staff who made this report possible. And our heartfelt thanks go to the almost 200 Covenant House New York youth who shared their stories with us. *For questions on the use of the trafficking screening tool discussed in this report or anything else related to the substance of the study, please contact study author, Jayne Bigelsen at [email protected] Table of Contents: Executive Summary . 5 Introduction . 5 Key Findings . 6 Terminology . 7 Objectives/Method . 8 Results and Discussion . 10 Compelled Sex Trafficking . 10 Survival Sex . 11 Relationship between Sex Trafficking and Survival Sex . 12 Labor Trafficking . 13 Contributing Factors . 14 Average Age of Entry into Commercial Sexual Activity . 16 Transgender and Gay Youth . 16 Development and Use of the Trafficking Assessment Tool . 17 Implications for Policy and Practice . 19 Conclusion . 21 Appendix: Trafficking Screening Tool . 22 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In recent years, the plight of human trafficking victims has received a great deal of attention among legislators, social service providers and the popular press. -

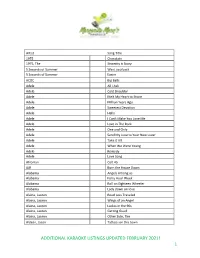

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start)