Chapter II Introspection and Definition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Salsa Bass the Cuban Timba Revolution

BEYOND SALSA BASS THE CUBAN TIMBA REVOLUTION VOLUME 1 • FOR BEGINNERS FROM CHANGÜÍ TO SON MONTUNO KEVIN MOORE audio and video companion products: www.beyondsalsa.info cover photo: Jiovanni Cofiño’s bass – 2013 – photo by Tom Ehrlich REVISION 1.0 ©2013 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 1482729369 ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐148279368 H www.beyondsalsa.info H H www.timba.com/users/7H H [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Bass Series...................................................................................... 11 Corresponding Bass Tumbaos for Beyond Salsa Piano .................................................................... 12 Introduction to Volume 1..................................................................................................................... 13 What is a bass tumbao? ................................................................................................................... 13 Sidebar: Tumbao Length .................................................................................................................... 1 Difficulty Levels ................................................................................................................................ 14 Fingering.......................................................................................................................................... -

Bzfen-Aniversario Colegio 1 a 6 B 133.Pdf

CIRCULAR Nº 133 Ref.: Aniversario colegio Estimados padres y apoderados(as): Tenemos el agrado de informar a ustedes las actividades organizadas para celebrar el aniversario N° 57 de nuestro colegio. A continuación detallamos el programa de estos días de celebración. LUNES 14 DE OCTUBRE Todas las actividades de 1° a 6° Básico finalizarán a las 13:15 horas. De 7° B a 4° Medio a las 13:00 horas con motivo de la celebración del Día del Profesor. MARTES 15 DE OCTUBRE Clases y talleres en horario regular. MIÉRCOLES 16 DE OCTUBRE: CLASES Y TALLERES EN HORARIO REGULAR JORNADA DE REFLEXIÓN (7° Básico a 4° Medio) El Centro de Estudiantes invita a los(as) alumnos(as) de 7° Básico a 4° Medio a un trabajo reflexivo que comenzará a las 8:30 horas y se extenderá hasta las 15:30 horas, incluyendo charlas brindadas por expertos en diferentes áreas, grupos de conversación y exposición de lo reflexionado. Los(as) alumnos(as) que no deseen asistir a esta actividad podrán seguir con sus clases habituales. JUEVES 17 DE OCTUBRE: DÍA DEL DEPORTE Y LAS ARTES Exposición de artes visuales y presentaciones artísticas de los(as) estudiantes. Competencias deportivas. Preparación de Alianzas. Los alumnos asisten con uniforme de Educación Física del colegio. Clases y talleres en horario regular, sólo se suspende la clase de Tecnología de 6° Básico por lo que este curso finalizará su jornada a las 15:30 horas. Los jefes de alianzas informarán a Inspectoría la nómina de alumnos de Enseñanza Básica (1° a 6° B) que se quedarán a ensayar coreografías hasta las 17:15 horas. -

Dans La Cantata Popular Santa María De Iquique

06,2 I 2021 Archiv für Textmusikforschung Identité(s) et mémoire(s) dans la Cantata popular Santa María de Iquique Olga LOBO (Grenoble)11 Summary The Cantata popular de Santa María de Iquique is one of the most important musical compositions of Quilapayún. Composed by Luis Advis in 1969 it tells the story of the massacre of the Iquique mineworkers in 1907. This cantata popular has become not only one of the symbols of the protest songs from the Seventies but also an icon for the universal struggle against injustice. The aim of this article is to study its history and different meanings in order to show the way how poetry, lyrics and music come together to tell the identities and memories of the Chilean people until now, when we celebrate its 50th anniversary. La Cantata de Luis Advis, une composition hybride et populaire La Cantata, entre deux traditions Interprétée pour la première fois en 1970 par le groupe Quilapayún, La Cantata popular Santa María de Iquique (Cantata) est une composition de Luis Advis (Iquique, 1935 – Santiago du Chili, 2005). Musicien autodidacte, il suivra dans les années 1950, une fois arrivé à Santiago, une formation classique avec Gustavo Becerra ou Albert Spikin. Si la tradi- tion classique sera déterminante pour la suite de sa carrière, les rythmes latino-américains ne font leur apparition dans le spectre de ses intérêts musicaux qu’à partir des années soixante. Son intérêt pour cette culture populaire était cependant tout relatif. Évoquant la genèse de la Cantata (dans une lettre du 15 mars 1984, envoyée à Eduardo Carrasco) Advis affirmera qu’à cette période-là il était un musicien « muy poco conocedor de la realidad popular musical y artística de [su] país » (Advis 2007, 16). -

¡Esto Parece Cuba!” Prácticas Musicales Y Cubanía En La Diáspora Cubana De Barcelona

Universitat de Barcelona Facultat de Geografia i Història Departament d’Antropologia Social i d’Història d’Amèrica i d’Àfrica Programa de Doctorat en Antropologia Social i Cultural Bienni 2003-2005 “¡Esto parece Cuba!” Prácticas musicales y cubanía en la diáspora cubana de Barcelona TESI DOCTORAL PRESENTADA PER IÑIGO SÁNCHEZ FUARROS codirigida pels Drs. Josep MARTÍ i PÉREZ i Gemma OROBITG CANAL Barcelona, 2008 A la memoria de mi padre, que se nos fue demasiado pronto. El exilio no es cosa del tiempo sino de espacios –por fundar, por huir, por conquistar- que cancelan la cronología de nuestras vidas. Iván de la Nuez, La balsa perpetua The exile knows his place, and that place is the imagination. Ricardo Pau-Llosa Imagination is not a place . You can´t live there, you can’t buy a house there, you can’t raise your children there. Gustavo Pérez-Firmat , Life on the Hyphen Tabla de contenidos Lista de ilustraciones 12 Prefacio 13 PARTE I – INTRODUCCIÓN 23 1. PRÓLOGO : LA MERCÉ CUBANA 25 2. LA DIÁSPORA CUBANA EN ESPAÑA 29 2.1 Generaciones diaspóricas 33 2.2 ¿Comunidad cubana en Barcelona? 46 3. PRÁCTICAS MUSICALES Y CUBANOS EN BARCELONA 54 3.1 Música, comunidad y cubaneo 54 3.2 Imaginarios musicales de lo cubano 58 3.3 La escena musical cubana en Barcelona 67 4. METODOLOGÍA 75 4.1 Las ciencias sociales y la diáspora cubana en España 77 4.2 La delimitación del obJeto de análisis 82 4.3 Los espacios de ocio como obJeto de análisis 90 4.4 Observador y participante 100 PARTE II – LAS RUTAS SOCIALES DEL CUBANEO 110 1. -

Meghan Trainor

Top 40 Ain’t It Fun (Paramore) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) All Of Me (Dance Remix) (John Legend) Am I Wrong (Nico & Vinz) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke) Break Free (Ariana Grande) Cake By The Ocean (DNCE) Can’t Feel My Face (The Weeknd) Cheerleader (OMI) Clarity (Zedd) Club Can’t Handle Me (Flo Rida) Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) Crazy In Love (Beyonce) Delirious (Steve Aoki) DJ Got Us Falling In Love (Usher) Dynamite (Taio Cruz) Feel So Close (Calvin Harris) Feel This Moment (Christina Aguilera, Pitbull) Fireball (Pitbull) Forget You (Cee Lo) Get Lucky (Daft Punk, Pharrell) Give Me Everything (Tonight) (Ne-Yo, Pitbull) Good Feeling (Flo Rida) Happy (Pharrell Williams) Hella Good (No Doubt) Hotline Bling (Drake) I Love It (Icona Pop) I’m Not The Only One (Sam Smith) Ignition Remix (R.Kelly) In Da Club (50 Cent) Jealous (Nick Jonas) Just The Way You Are (Bruno Mars) Latch (Disclosure, Sam Smith) Let’s Get It Started (Black Eyed Peas) Let’s Go (Calvin Harris, Ne-Yo) Locked Out Of Heaven (Bruno Mars) Miss Independent (Kelly Clarkson) Moves Like Jagger (Maroon 5, Christina Aguilera) P.I.M.P. (50 Cent) Party Rock Anthem (LMFAO) Play Hard (David Guetta, Ne-Yo, Akon) Raise Your Glass (Pink) Rather Be (Clean Bandit, Jess Glynne) Royals (Lorde) Safe & Sound (Capital Cities) Shake It Off (Taylor Swift) Shut Up And Dance (Walk the Moon) Sorry (Justin Bieber) Starships (Nicki Minaj) Stay With Me (Sam Smith) Sugar (Maroon 5) Suit & Tie (Justin Timberlake) Summer (Calvin Harris) Talk Dirty (Jason DeRulo) Timber (Kesha & Pitbull) Titanium (David Guetta, -

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House

RED HOT + CUBA FRI, NOV 30, 2012 BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Music Direction by Andres Levin and CuCu Diamantes Produced by BAM Co-Produced with Paul Heck/ The Red Hot Organization & Andres Levin/Music Has No Enemies Study Guide Written by Nicole Kempskie Red Hot + Cuba BAM PETER JAY SHARP BUILDING 30 LAFAYETTE AVE. BROOKLYN, NY 11217 Photo courtesy of the artist Table Of Contents Dear Educator Your Visit to BAM Welcome to the study guide for the live The BAM program includes: this study Page 3 The Music music performance of Red Hot + Cuba guide, a CD with music from the artists, that you and your students will be at- a pre-performance workshop in your Page 4 The Artists tending as part of BAM Education’s Live classroom led by a BAM teaching Page 6 The History Performance Series. Red Hot + Cuba is artist, and the performance on Friday, Page 8 Curriculum Connections an all-star tribute to the music of Cuba, November 30, 2012. birthplace of some of the world’s most infectious sounds—from son to rumba and mambo to timba. Showcasing Cuba’s How to Use this Guide diverse musical heritage as well as its modern incarnations, this performance This guide aims to provide useful informa- features an exceptional group of emerging tion to help you prepare your students for artists and established legends such as: their experience at BAM. It provides an Alexander Abreu, CuCu Diamantes, Kelvis overview of Cuban music history, cultural Ochoa, David Torrens, and Carlos Varela. influences, and styles. Included are activi- ties that can be used in your classroom BAM is proud to be collaborating with and a CD of music by the artists that you the Red Hot Organization (RHO)—an are encouraged to play for your class. -

Violeta Parra, Después De Vivir Un Siglo

En el documental Violeta más viva que nunca, el poeta Gonzalo Rojas llama a Violeta la estrella mayor de Chile, lo más grande, la síntesis perfecta. Esta elocuente descripción habla del sitial privilegiado que en la actualidad, por fin, ocupa Violeta Parra en nuestro país, después de muchos años injustos en los que su obra fue reconocida en el extranjero y prácticamente ignorada en Chile. Hoy, reconocemos a Violeta como la creadora que hizo de lo popular una expre- sión vanguardista, llena de potencia e identidad, pero también como un talento universal, singular y, quizás, irrepetible. Violeta fue una mujer que logró articular en su arte corrientes divergentes, obligándonos a tomar conciencia sobre la diversidad territorial y cultural del país que, además de valorar sus saberes originarios, emplea sus recursos para pavimentar un camino hacia la comprensión y valoración de lo otro. Para ello, tendió un puente entre lo campesino y lo urbano, asumiendo las antiguas tradi- ciones instaladas en el mundo campesino, pero también, haciendo fluir y trans- formando un patrimonio cultural en diálogo con una conciencia crítica. Además, construyó un puente con el futuro, con las generaciones posteriores a ella, y también las actuales, que reconocen en Violeta Parra el canto valiente e irreve- rente que los conecta con su palabra, sus composiciones y su música. Pero Violeta no se limitó a narrar costumbres y comunicar una filosofía, sino que también se preocupó de exponer, reflexionar y debatir sobre la situación política y social de la época que le tocó vivir, desarrollando una conciencia crítica, fruto de su profundo compromiso social. -

Violeta-Parra.Pdf

Tres discos autorales Juan Pablo González Fernando Carrasco Juan Antonio Sánchez Editores En el año del centenario de una de las máximas expresiones de la música chilena, Violeta Parra, surgió este proyecto que busca acercarnos a su creación desde su faceta de compositora y creadora de textos. La extensa obra de Violeta –que excede lo musical y llega a un plano más amplio del arte– se caracteriza en música por un profundo trabajo de recopilación primero y, posteriormente, por la creación original de numerosas canciones y temas instrumentales emblemáticos que –como Gracias a la Vida– han sido aquí por primera vez transcritas, en un ejercicio que busca llevar estas obras de carácter ya internacional, al universal lenguaje de la escritura musical y, con ello, ampliar el conoci- miento de su creación única y eterna. Violeta es parte de nuestra historia musical, y nuestra organización –que agrupa a los creadores del país y que tiene como misión proteger el trabajo que realizan por dar forma a nuestro repertorio y patrimonio– recibe y presenta con entusiasmo esta publicación, que esperamos sea un aporte en la valorización no sólo de la obra de esta gran autora, sino de nuestra música como un elemento único y vital de identidad y pertenencia. SOCIEDAD CHILENA DE AUTORES E INTÉRPRETES MUSICALES, SCD Violeta Parra Tres discos autorales Juan Pablo González, musicología Fernando Carrasco y Juan Antonio Sánchez, transcripción Osiel Vega, copistería digital Manuel García, prólogo Isabel Parra y Tita Parra, asesoría editorial Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado Alameda 1869 - Santiago de Chile [email protected] - 56-228897726 www.uahurtado.cl Este libro fue sometido al sistema de referato ciego externo Impreso en Santiago de Chile en el mes de octubre de 2018 por C y C impresores ISBN libro impreso: 978-956-357-162-2 ISBN libro digital: 978-956-357-163-9 Coordinadora colección Música Daniela Fugellie Dirección editorial Alejandra Stevenson Valdés Editora ejecutiva Beatriz García-Huidobro Diseño de la colección y diagramación interior Gabriel Valdés E. -

Música Artes Musicales Prof

Departamento de música Artes Musicales Prof. Santiago Concha C. Música • SEMANA Nº: 1 • CLASE: Nº • CURSO: III medio electivo • DOCENTE: Santiago Concha C. • CORREO ELECTRÓNICO: [email protected] OBJETIVOS: Reconocer elementos distintivos del periodo en cuanto a las temáticas, instrumentos y sonoridades del periodo CONTENIDOS DE LA SEMANA: Nueva canción chilena y canto nuevo (Violeta Parra y los jaivas) • DESARROLLO Recordar información comentada en clases, se considerará el inicio del movimiento desde el año 64, debido a que hay grupos del aquel movimiento que aún siguen activos este no terminará en un año especifico. Considerar que, si bien Violeta Parra no se desarrolló activamente durante todo este periodo debido a su temprana muerte, fue sin duda alguna la canalizadora y guía para muchos de los solistas o grupos que se desarrollaron artísticamente en los años posteriores. Algunos artistas importantes e ineludibles de la época son: • Violeta Parra • Víctor Jara • Rolando Alarcón • Ángel e Isabel Parra • Patricio Manns • Santiago del nuevo extremo • Inti Illimani • Quilapayun • Sol y lluvia • Illapu • Los jaivas Dado lo anterior adjuntaré unos links con canciones o conciertos en vivo donde les pediré que investiguen o pongan atención en los siguientes detalles: Ø Link 1 Análisis realizado por un Español bastante conocido en YouTube, este video es su primera vez analizando a los jaivas, específicamente la poderosa muerte, es necesario que cuando escuchen música y vean los videos que adjuntaré vean todos los detalles tal como lo hace este sujeto en su canal, obviamente lo que desconozcan en cuanto a instrumentos investíguenlo y no se queden como el que básicamente dice algunas barbaridades, sin embargo, esto se puede entender ya que es un mundo instrumental y sonoro más cercano a nosotros que a él. -

Spanglish Code-Switching in Latin Pop Music: Functions of English and Audience Reception

Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 II Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 © Magdalena Jade Monteagudo 2020 Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception Magdalena Jade Monteagudo http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The concept of code-switching (the use of two languages in the same unit of discourse) has been studied in the context of music for a variety of language pairings. The majority of these studies have focused on the interaction between a local language and a non-local language. In this project, I propose an analysis of the mixture of two world languages (Spanish and English), which can be categorised as both local and non-local. I do this through the analysis of the enormously successful reggaeton genre, which is characterised by its use of Spanglish. I used two data types to inform my research: a corpus of code-switching instances in top 20 reggaeton songs, and a questionnaire on attitudes towards Spanglish in general and in music. I collected 200 answers to the questionnaire – half from American English-speakers, and the other half from Spanish-speaking Hispanics of various nationalities. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

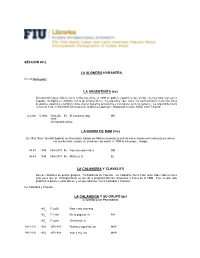

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

Tesis (959.4Kb)

LA CANCIÓN Y EL CANTAUTOR LATINOAMERICANO CONTEMPORÁNEO DANIEL JOSÉ RIVERA MARIÑO UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BUCARAMANGA FACULTAD DE MÚSICA BUCARAMANGA 2013 LA CANCIÓN Y EL CANTAUTOR LATINOAMERICANO CONTEMPORÁNEO DANIEL JOSE RIVERA MARIÑO Trabajo de Grado presentado para optar por el título de Maestro en Música Docente Asesor ADOLFO HERNÁNDEZ UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BUCARAMANGA FACULTAD DE MUSICA BUCARAMANGA 2013 Nota de aceptación: ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Firma del presidente del jurado ____________________________________ Firma del jurado ____________________________________ Firma del jurado Bucaramanga, Septiembre de 2013 Página de dedicatoria TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. REPERTORIO ................................................................................................... 5 2. CONTEXTUALIZACION .................................................................................... 6 2.1 LA FORMA MUSICAL....................................................................................... 6 2.2 LA TRADICIÓN ................................................................................................. 9 2.2.1 PASILLO . ......................................................................................................... 11 2.2.2 BAMBUCO . .....................................................................................................